Learning that our own Solar System has a configuration that is only one of many possible in the universe leads to a certain intellectual exhilaration. We can, for example, begin to ponder the problems of space travel and even interstellar missions within a new context. Are there planetary configurations that would produce a more serious incentive for interplanetary travel than others? What would happen if there were not one but two habitable planets in the same system, or perhaps orbiting different stars of a close binary pair like Centauri A and B?

My guess is that having a clearly habitable world — one whose continents could be made out through ground-based telescopes, and whose vegetation patterns would be obvious — as a near neighbor would produce a culture anxious to master spaceflight. Imagine the funding for manned interplanetary missions if we had a second green and blue world that was as reachable as Mars, one that obviously possessed life and perhaps even a civilization.

Solar systems with multiple habitable planets are the subject of an interesting new paper from Jason Steffen (UNLV) and Gongjie Li (Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics), who point to the fact that the Kepler mission has found planet pairs on similar orbits, with orbital distances that in some cases differ by little more than 10 percent. Mars is at best 200 times as far away as the Moon, but as Steffen notes, multi-habitable systems will produce much closer destinations:

“It’s pretty intriguing to imagine a system where you have two Earth-like planets orbiting right next to each other,” says Steffen. “If some of these systems we’ve seen with Kepler were scaled up to the size of the Earth’s orbit, then the two planets would only be one-tenth of one astronomical unit apart at their closest approach. That’s only 40 times the distance to the Moon.”

We can’t know at this point whether any of the Kepler candidates have life or not, but consider this: Kepler-36, about 1530 light years away in the constellation Cygnus, is known to be orbited by a ‘super-Earth’ and a ‘mini-Neptune’ in orbits that differ by 0.013 AU. The outer planet orbits close enough to the inner that we can pick up obvious transit timing variations (TTV) for both. Locked in a 7:6 orbital resonance, these worlds are representative of this kind of planetary configuration. Imagine the changing celestial display from the surface of the super-Earth as the larger planet sweeps out its orbit. Now consider the same view if both planets were clearly habitable!

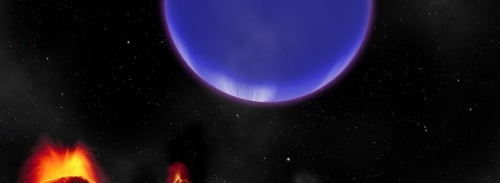

Image: A gas giant planet spanning three times more sky than the Moon as seen from the Earth looms over the molten landscape of Kepler-36b. Credit: Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics.

Steffen and Li focus in on two key issues. Specifically, what sort of variations in obliquity might be caused by such close planetary orbits? Obliquity measures the angle between the planet’s spin and its orbital axis — Earth’s 23.5° tilt relative to its orbit explains seasonal change and has obvious effects on climate. So we’d like to know whether close orbits disrupt planetary climates enough to wreak climatic havoc. The answer in most cases is no. From the paper:

We found that obliquity variations are generally not affected by the close proximity of the planets in a multihabitable system. Also, obliquity variations of close pairs embedded in the solar system or of potentially habitable planets in a system with a close pair were not sufficient to significantly reduce the probability of having a stable climate. Only in cases where the inclination modal frequencies coincide with the planetary precession frequency did large obliquity variation arise.

With planets this close, however, an even larger question is whether life on one planet can influence the other. We have abundant evidence of rocks from Mars that have fallen to Earth, leading to the possibility that other planets could have delivered life-bearing materials here in the process called lithopanspermia. Much closer planets should be far more susceptible to this process. Clearly, the possibility exists for life branching out from the same roots, taking different evolutionary paths just as occurs on remote islands here on Earth.

The simulations used by Steffen and Li demonstrate that two Earth-like planets in orbits like those found around Kepler-36 would have a much greater opportunity for exchanging materials than planets do in our Solar System. The relative velocities of the planets — and thus the velocities of the ejected particles — would be much less than in the case of a transfer of materials from Mars to the Earth. Biological materials transferred by collision ejecta have been considered on individual planets (with material falling back onto other parts of the same world), between binary planets or habitable moons, and even between different star systems.

Steffen and Li’s simulations show that the nearer the planets are to each other, the higher the success rate of ejecta transfer. Moving biological materials between two worlds becomes almost as feasible as moving them from one place on a single planet to another region of that planet, and the energy of the impact needed to make the transfer is much less than in our Solar System, leading to higher survivability. We can add in the fact that the time needed for biological materials to survive an interplanetary journey is that much shorter.

And there is this final factor:

…we found that the smaller the velocity of the ejected material the more uniformly they can be sourced across the originating planet. With high velocity ejecta, the range of initial longitudes is constrained relative to the direction of motion.

The result: Debris from a single impact is far more likely to strike the destination planet at multiple locations in rapid succession than when planets are spaced farther apart. That too increases the chance of life catching hold. Processes like these, which could also occur around planets with large habitable moons, allow life to spread readily within the same system. The paper adds:

Not only will panspermia be more common in a multihabitable system than in the solar system, but the close proximity of the planets to each other within the habitable zone of the host star allows for a real possibility of the planets having regions of similar climate—perhaps allowing the microbiological family tree to extend across the system. There are many things to consider in multihabitable systems, especially in the cases where intelligent life emerges.

In this UNLV news release, Steffen follows up that last thought:

“You can imagine that if civilizations did arise on both planets, they could communicate with each other for hundreds of years before they ever met face-to-face. It’s certainly food for thought.”

The scenario is striking, and I’m hoping readers can come up with some science fiction titles in which multiple habitable planets in the same system are the background for the tale.

The paper is Steffen and Li, “Dynamical considerations for life in multihabitable planetary systems,” accepted at The Astrophysical Journal (preprint).

This is all very good and well, and I imagine we can think of all kinds of rosy scenarios that would have continents and oceans that are teeming with life and perhaps even super intelligent beings on these planets, etc. etc. etc.

but I believe that in the long run a more sensible view will prevail despite all this hype of largely fictitious probable scenarios. We probably should look at the fact that what we had here is unique rather than all pervasive throughout the universe. For example, there is going to be plenty of worlds in which they have temperate climates, water, and are perhaps as barren of life as the moon itself.

And then we have to come back to the issue of who is going to pay for all this; it’s nice to imagine everybody gathering together and demanding that a huge expedition be mounted to go to this probable New World, but what happens when they find out it’s going to cost the equivalent of the material value of the United States and Russia combined ? I don’t believe that the world is going to be willing to gamble that kind of money on what would be arguably a mere wisp of a chance of it being a second earth. I think we’ve reached a point in our history in which very pedestrian matters will start to take forefront of all that we do in this world.

No, worlds with temperate climates and water are going to be easy for life to evolve upon. And future technology will make interstellar travel much cheaper, and we can use multiple telescopes spread out in solar orbit to image these planets.

Dan Dare comic strip. 2 stories as part of a linked story arc:

“The Man from Nowhere” and “Rogue Planet”

The close worlds are” Cryptos and Phantos. The 2 species are the similar looking Crypts and Phants. Their home system of Los is clearly based on Alpha Centauri. The 2 worlds get close enough for the Phants to invade Cryptos on a regular schedule but separated by very many years. I don’t think this suggests an orbital resonance, just slight different in orbital distance only.

Mirror Worlds (title) Unfortunately, the perceived difference and threat lead to their solar system warfare. This leads them to developing interstellar capabilities.

On one hand, I think that we will find a million times more exoplanets with mere bugs on them, rather than carbon copies of Earth.

On the other hand, if the AC system does have a pair of habitable worlds, and one is occupied by beings who are at least close to becoming space-faring, you can bet that they would be all over that second world as well, as we would be as well.

Two life bearing planets giving rise to sentient life in the same single sun solar system is a tough Odds outcome. If we add, becoming technological

civs at the nearly the same time, is the type of stuff a multi-verse might

have in one case. One universe is not enough to make this a possibility.

Also unless it’s a double sun system like AB centauri, one planet

will have a shorter habitability window compared to the other. At any

rate I am no so sure planets in the same HZ, are stable over Eons of time, since we are talking about a band of maybe 20 Million miles, in order for both planets to have significant time as abodes for life, I know the HZ can be

larger but, we talking stability folks.

Imagine where humanity might be if Percival Lowell was right about Mars:

http://www.wanderer.org/references/lowell/Mars/

Then again imagine if H. G. Wells was right….

http://www.shmoop.com/war-of-the-worlds-hg-wells/

This is a neat series of blog posts playing with some ideas for “super habitable” solar systems. It tries to maximize the number of worlds in a star’s habitable zone for the maximum amount of time.

http://planetplanet.net/2014/05/23/building-the-ultimate-solar-system-part-5-putting-the-pieces-together/

The scenario building ends up with a bunch of binary planets rather more packed together than in our solar system. It’s a fun thought experiment…

Wow! straight out of a 1950’s Heinlien novel. How about “Between Planets”?

If the two planets are biologically related then the potential exists for nasties like the transmission of diseases between planets as well as positives like exploration and colonisation.

In reality I think that the chances of the two planets having two species at roughly the same stage of development are small its more likely that one species could be millions of years ahead of the other. Still more likely is that the planets are different enough in size and other characteristics to make their environments substantially different from each other.

Re panspermia: Let us not forget that it remains wild speculation, no matter how close the orbits. Any life to be transferred must survive the ejection process, the space environment, and the not-so-soft landing. Then, most improbable of all, it must miraculously find itself in an environment in which it can grow. On a different, sterile world. I just don’t buy it.

Odds are one would develop intelligent life, and given the necessary resources, space flight, millions of years before the other, which leads to the question of what they would do to the second planet. Or what if they did not have the resources for “manned” space flight but they could launch rockets there. If they detect intelligent life on the neighbor planet do they encourage that intelligence or do they get frightened, like it appears humans would, and try to destroy it?

Interesting question you posed.

A more likely scenario for two alien species coming to intelligence at about the same time, in the same solar system, is to have them on two small islands on an otherwise oceanic world. The islands should be on opposite sides of the planet. Then the timing issues are not so formidable as on two planets in the same solar system, or two planets around separate stars in a binary system, the other two possibilities. Some tentative discussion of this is here:

http://stanericksonsblog.blogspot.com/2015/10/solar-systems-with-two-alien_6.html

I think that at best life on worlds in the same habitable zone will have common metabolism and information storage. Beyond that they will be highly divergent. Even if we rerun evolution the outcomes will be wildly different.

What is certain is that there could not be comparable ETIs with similar technological levels.

I’m not quite as skeptical as Eniac regarding successful panspermia, although I am cognizant of the difficulties of culturing bacteria in what we think are highly suitable conditions. Bugs may find it extremely hard to gain a foothold in a literally alien environment.

For a while we had this situation here in the solar system, at least before the sun brightened up and runaway greenhouse got going on Venus……..

Given the exchange of material with Earth, it almost certainly had life too. And so did Mars.I remember reading that ejected Earth rocks could make it to Saturn system. That could include Europa and Enceladus too.

Spycos 4 by Peter Dagmar.

I find possibility of life of similar biology arising on both the planets is really awesome. But to think of intelligent life on both is preposterous. For intelligent life to evolve we need something like our Moon to stabilize, axis of rotation. otherwise I think possibility of two life bearing moons of Gas Giant is more than the two planets on close proximity.

I’m thinking of a (very) fanciful movie that posits two worlds so close they appear as upside down to one another…maybe someone else has the title? Of course young lovers work to join one another in the two worlds.

The science in this story is a bit weak, to say the least.

There’s also the Ursula K. LeGuin story “The Dispossessed”. That’s all that come to mind this early morning.

And to all of you naysayers commenting before me, wailing about costs and probabilities, I say: Away with you! Today’s post from friend Paul in habits the Land of Fiction, so let’s have a bit of fun with it.

Imagine our solar system with Mars and Venus exchanged…

I have always been fascinated by the possibility of star systems with two planets in the habitable zone. Imagine the effect on early humanity if Mars were close enough for us to see the seasonal wax and wane of foliage. If there had been a world that more obviously mirrored our own would would our religions and notions of an after life be dominated by that planet? All speculations of course, but I think humanity would have taken planetary exploration much more seriously and few would debate whether or not we would become a multi-planetary species.

Would successful panspermia be more likely to occur for the building blocks of life rather than the finished products? Perhaps life is more likely to emerge within systems with two planets in the habitable zone. There is the obvious doubling of chance because there are two planets as well as the opportunity for each planet to supplement the process of the other planet through panspermia.

@ Michael Spencer

Are you talking about “Upside Down”? Netflex keeps recommending the movie but I keep saying no. “The Dispossessed” is the first story that came to mind for me as well, though it doesn’t really delve into how the existence of two habitable planets affected the early development of an intelligent species.

Basically most pre-1960 science fiction depicts a star system with multiple habitable worlds: the Solar System.

In Star Trek the Rigel star system has at least four inhabited planets!

http://memory-alpha.wikia.com/wiki/Rigel_system

Just ignore the fact that the Rigel in our Universe is only 10 million years old and a Class B sugergiant star, please….

http://www.space.com/22872-rigel.html

@Eric, I wonder how orbital resonance would apply in such a populated system.

Harold:

No. The “building blocks” of life are plentiful in many places, so space delivery is not really needed. In any case, anything that is not alive and not present in the target world would very quickly be diluted to nothingness and have no effect. Only fully independent autotrophs, i.e. life forms that can thrive under completely abiotic conditions, could possibly take hold, and only if they are delivered fully intact. Autotrophs exist, obviously, but most life forms are not.

Enzo:

Invalid conclusion, that. It is quite plausible that exchange of material does not mean exchange of life. I’ll grant you “might” instead of “almost certainly”

Pranay:

That does make no sense to me. Life, but not intelligent without a stable axis of rotation? How come?

Would there not be a huge issue regarding gravitational effects – the geological chaos that mutual proximity would bring to this scenario? Think of how our own relatively small moon exerts such an influence on the surface of the earth.

Harold,

Yes, that’s it. the movie is odd for lots of reasons but I enjoyed it.

The Dispossessed by Ursula K. LeGuin is the two planet civilization story that sticks in my mind. I seem to remember Anarres was settled by refugees from Urras so I think it was one planet colonizing the other.

The SF solar system of my youth had Venus, Mars , asteroid belt and some moons colonized to varying degrees. In Heinlein’s Between Planets both Venus and Mars have colonies that are in revolt against the Earth. Many ‘alternate’ universes in SF had the ‘Solar System’ colonized first before there is interstellar flight.

Two predictions:

When we finally come across extraterrestrial life, it will be so exotic that humanity will struggle with whether it fits our definition of life, for decades.

When we finally find extraterrestrial intelligence, we will likewise refuse to acknowledge it, at least initially.

It has been almost twenty years since the announcement of the findings in the Martian meteorite ALH84001 (oy!) and the true nature of those little “microfossils” are still being debated.

I am also reminded of Stanislaw Lem’s Solaris and His Master’s Voice, which are probably among the more realistic science fiction novels in terms of how humans will attempt to understand and react to truly alien life.

Interesting article on the information issue of a genesis and the likelihood of a another genesis.

Bit by Bit: The Darwinian Basis of Life

Abstract: All known examples of

life belong to the same biology, but

there is increasing enthusiasm

among astronomers, astrobiolo-

gists, and synthetic biologists that

other forms of life may soon be

discovered or synthesized. This

enthusiasm should be tempered

by the fact that the probability for

life to originate is not known. As a

guiding principle in parsing poten-

tial examples of alternative life, one

should ask: How many heritable

‘‘bits’’ of information are involved,

and where did they come from? A

genetic system that contains more

bits than the number that were

required to initiate its operation

might reasonably be considered a

new form of life.

I can think of two hard-science novels that involve pairs of habitable worlds in the same system where the habitability of both worlds is central to the plot. The first on to come to mind is Edward McSweegan’s novel Alpha Transit which posits habitable worlds orbiting each of the Alpha Centauri suns. The biospheres are reasonably well described and one of the planets actually has a hive-dewlling paleolithic sentient species. The second novel – more accurately, a shared-universe novel is Murasaki, edited by Robert Silverberg which deals with a binary world orbiting the red dwarf HD 36395 some twenty light-years from Sol. The astronomy, exobiology and geology are very well-fleshed out and the appendix by Poul Anderson is a brilliant piece of world-building – IMHO it is very well worth purchasing.

Phil, just read Murasaki and I have to thank you for this wonderful suggestion. A recommended read that fits expectations of a realistic depiction of another planet and biosphere.

Eric December 1, 2015 at 18:59:

“This is a neat series of blog posts playing with some ideas for “super habitable” solar systems. It tries to maximize the number of worlds in a star’s habitable zone for the maximum amount of time.”

Interesting how superhabitable is defined here: as the maximum number of habitable planets during the maximum time.

In another very interesting post here, the concept of ‘superhabitability’ was introduced and discussed, be it in a somewhat different way, rather with regard to the individual planet than the number of planets in one system. But maybe the two can be combined and redefined.

https://centauri-dreams.org/?p=29867

Not sure where to put it, but this very interesting article is just in, on ScienceDaily:

What kinds of stars form rocky planets?

http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2015/12/151203150323.htm

“Their work shows that small rocky planets like Earth do not preferentially form around stars rich in metallic elements such as iron and silicon. (…) Our results support the theory that the formation of small, rocky planets can occur around stars with diverse elemental compositions. This means that small, rocky planets may be even more commonplace than we previously thought.”

@Ronald. That is curious. Until recently our sample of Earthlike planets has been N=1. Maybe the formed planets used up their star’s metal supply?

@TLDR: I am not sure I understand what you mean, but I had intended to leave this (potentially very interesting) discussion to a separate post on this article. Paul?

Tip of the veil: there have other studies and articles suggesting the same, i.e. that small rocky planets can form around stars with even low metallicity (e.g. Tau Ceti, 82 Eridani), contrary to gas giants that require high metallicity.

Personally, as a fascinated amateur, I think that there are (at least) 3 different types of planetary systems that can host small rocky planets.

But I rather leave that to a another dedicated post by Paul on this topic.

This intriguing question is even more interesting in view of possible life bearing exomoon with technological civilization(I do understand the problems with habitable moons, but they are still possibility). A civilization arising on such moon, would have easy access to multiple other moons potentially terraformable or easily used as resource sources. One could imagine that with such easy access it would develop into an interplanetary one pretty quickly.

“ljk December 1, 2015 at 17:34

Imagine where humanity might be if Percival Lowell was right about Mars:

http://www.wanderer.org/references/lowell/Mars/”

You might be interested in light SF novel by SM Stirling

“In the Courts of the Crimson Kings” where this precise scenario is explored, with both USA and USSR discovering Mars as alive and with ancient civilizations present(there is a sequel with Venus as well).

Phil Tynan-the Murasaki story you mentioned seems interesting, I have ordered a copy of the paperback already!

I was going to suggest Murasaki too.

While Ursula K. LeGuin has been mentioned I’d like to add most of the ‘Pern’ books… Pern is seeded by the ‘Thread’ every century or so so the Dragonriders have their work cut out.

My all time favourite author, the late Iain M Banks, wrote ‘Against a Dark Background’ featuring the utterly isolated Thrial system with Golter as the main planet. The story is spread over a few of the systems habitable (and IIRC colonized) planets.

(I may not be quick but I spotted my error eventually…)

It was Anne McCaffrey who wrote the ‘Pern’ novels so there’s no excuse for me cut’n’pasting the wrkng female author, ooops!