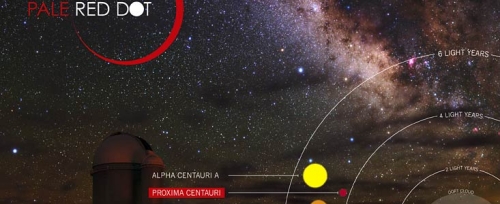

A new observational campaign for Proxima Centauri, coordinated by Guillem Anglada-Escudé (Queen Mary University, London), is about to begin, an effort operating under the name Pale Red Dot. You’ll recall Dr. Anglada-Escudé’s name from his essay Doppler Worlds and M-Dwarf Planets, which ran here in the spring of last year, as well as from Centauri Dreams reports on his work on Gliese 667C, among other exoplanet projects. Pale Red Dot is a unique undertaking that brings the public into an ongoing campaign from the outset, one whose observations at the European Southern Observatory’s La Silla Observatory begin today.

The closest star to our Sun, Proxima Centauri was discovered just over 100 years ago by the Scottish astronomer Robert Innes. A search through the archives here will reveal numerous articles about the red dwarf and the previous attempts to find planets orbiting it. I’ll point you to a round-up of exoplanet work on Proxima thus far next week, when my essay ‘Intensifying the Proxima Centauri Planet Hunt’ will run as part of Pale Red Dot’s outreach campaign. For now, the short summary is that we can rule out various planet scenarios around Proxima, but the possibility of a rocky world in the habitable zone is definitely still in the mix.

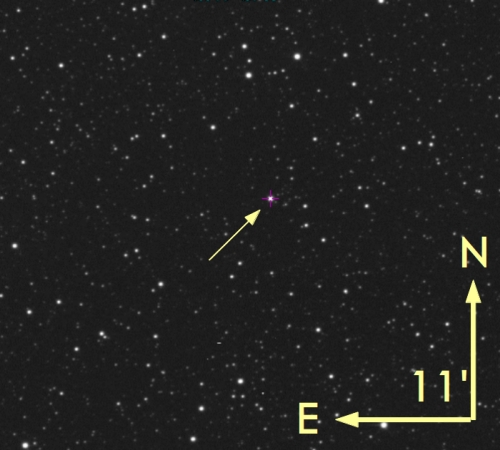

Image: First images of Proxima from the Las Cumbres Observatory Global Telescope Network at Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory, Chile.

Pale Red Dot today begins a two and a half month campaign that will run through April using the HARPS spectrograph at ESO’s 3.6-meter telescope at La Silla (Chile). The method here is radial velocity, looking for those infinitesimal Doppler signals showing the star’s motion as affected by planetary companions. These RV studies thus add to the earlier work done by Michael Endl (UT-Austin) and Martin Kürster (Max-Planck-Institut für Astronomie), who studied Proxima using the UVES spectrograph at the Very Large Telescope in Paranal.

But Pale Red Dot’s HARPS data will be complemented by robotic telescopes around the globe, including the Burst Optical Observer and Transient Exploring System (BOOTES) and the Las Cumbres Observatory Global Telescope Network (LCOGT). These automated installations will measure the brightness of Proxima each night during the observing campaign, helping to clarify whether any RV ‘wobbles’ of the star are caused by a planet or by events on the stellar surface. After thorough data analysis, the results will be submitted to a peer-reviewed journal.

The public outreach aspect of Pale Red Dot is compelling. Anglada-Escudé explains:

“We are taking a risk to involve the public before we even know what the observations will be telling us — we cannot analyse the data and draw conclusions in real time. Once we publish the paper summarising the findings it’s entirely possible that we will have to say that we have not been able to find evidence for the presence of an Earth-like exoplanet around Proxima Centauri. But the fact that we can search for such small objects with such extreme precision is simply mind-boggling.

“We want to share the excitement of the search with people and show them how science works behind the scenes, the trial and error process and the continued efforts that are necessary for the discoveries that people normally hear about in the news. By doing so, we hope to encourage more people towards STEM subjects and science in general.”

To communicate the process, Pale Red Dot will use blog posts and social media, with essays from astronomers, scientists, engineers and science writers on the site’s blog. To keep up with the social media updates, use @Pale_red_dot on Twitter for the project account, and you’ll probably want to check the hashtag #PaleRedDot as well. I also want to mention (and this will be in my article next week) that David Kipping’s transit studies of Proxima using the Canadian MOST (Microvariability & Oscillations of STars) space telescope are continuing, and beyond this we have another gravitational microlensing possibility as the star occults a 19.5-magnitude background star this February. Proxima Centauri, 2016 looks to be your year, and perhaps it’s also the year we find out for sure whether there is a planetary system so close to our own.

The is great news about ESO’s Pale Red Dot campaign. I can’t wait to see how this turns out! A description of what earlier searches for exoplanets of Proxima Centauri have found (or, more precisely, not found) can be found here:

http://www.drewexmachina.com/2015/02/23/the-search-for-planets-around-proxima-centauri/

The paper on this February’s microlensing possibility. A campaign for this event needs both astrometry and photometry, to catch motion of the centroid of the star, and a possible brightening due to lensing from exoplanets.

http://arxiv.org/abs/1401.0239

I have been following the Proxima Centauri planet search for a few years now (both here and on Andrew LePage’s excellent site) for a few years now – but I am a bit puzzled what this “potential signal of an Earth-like planet” refers to: is this something publicly known / published in the literature? I cannot imagine that this just refers to the upper limit of 2-3 Earth masses in the HZ of Proxima. Do we have a potential signal from the first microlensing event in October 2014? Or should I just wait for the article to come out? :)

Bynaus, I think you’re drawing the phrase “potential signal of an Earth-like planet” from the ESO site, right? I’m not clear on that reference either, but I will be going through earlier exoplanet findings for Proxima next week (and will link to the article). If I learn anything more about the ‘potential signal,’ I’ll report in on it here.

” Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.”

When compared to the technology of my youth instruments like HARPS are pointing to that reality. I can’t get over the precision of modern instrumentation.

@Paul, yes, in the ESO video, they mention it (1:20 onwards). Actually, they do not say “Earth-like” there, but on the introduction page of the palereddot.org website, they say: “After years of data acquisition by many researchers and teams, a signal has been identified which may indicate the presence of an Earth-like planet.” So they must know something “we” currently don’t – or perhaps missed, hence my question. A recent tweet by the PRD team also refers to a “signal”: https://twitter.com/Pale_red_dot/status/688441284290310144

I am also amazed by the precision of modern instruments used to look for exoplanets! The hunt for planets around Proxima is exciting indeed. What do others think about the likelihood of small planets around this red dwarf based on planet formation theory? The Kepler mission has given us some idea as to how common planets are around a variety of stellar spectral classes, including M dwarf stars. I remember reading that Kepler looked mostly at larger M dwarfs relative to our neighbor, but what, if anything, do the Kepler mission results on M dwarf planet frequency have to say about the probability of finding terrestrial planets around Proxima?

Bynaus writes:

OK, right, I think I’ve got that reference, but I’m waiting on permission to give the details. More later in the day, I hope.

Lots of RV “noise” around Proxima but the provisional “signal” I believe is for a terrestrial sized planet within the habitable zone with a suggestion of an 18 day Period. Thanks to the increasingly deep search , we are getting closer with each search ( Gaia being the latest and ongoing ) to the sort of precision astrometry that will confirm any planets or not especially the cumulative data . I welcome the decision to involve everyone rather than making this sit of thing the domain of few skilled individuals . It’s what astronomy is all about. Thanks to Dr Anglada-Escude for his openness in sharing with “Centauri Dreams” so early and submitting his work to early high level scrutiny . A great compliment to both him , the Editor and the site I think . In conjunction with the ongoing balanced debate on Kepler findings and Dyson spheres and such the like it is testament to the ongoing quality that both public and professionals alike have come to expect.

Dear Bynaus

I’m Guillem from Pale Red Dot. Yes, we have evidence for a signal from high cadence observations with HARPS (unpublished but publicly available) where the star seems to wobble over the course of two separate 10 day runs. While statistically significant, it is ambiguous in the sense that does not pinpoint a precise period (several options in the range between 10 and 30 days). On top of that, and as reported by Endl & Kuester, the star is variable in the few hundred days range…

We were planning a non-technical article on it, but we might put the observing proposal as well so people with some more technical background can form a more educated opinion. Again, we are talking about a signal (inconclusive evidence but sufficient to convince the telescope allocation panel to grant the time), and it might well be caused by activity. The ‘magic’ ingredient of the Pale Red Dot campaign is the regular sampling over a number of putative periods together with the photometry. Let’s hope it works so we can conclude something one way or the other… (worst case scenario observations can inconclusive again!)

If this would have been another star, we would probably have thrown it to the recycle bit and have moved on… fingers crossed

Kepler amongst others says you find less planets around smaller stars and especially late M, such as M5 Proxima, but those planets you do find are smaller and more likely to be rocky.

This is why less sexy , “one off ” microlensing studies such as those to be completed by WFIRST are so important as they give estimates on most sized planets around most sized stars.

I’m puzzled by the emphasis on RV with regard to the PRD. Haven’t radial velocity studies been done already? And don’t they require data to be gathered over a long period than a few months? I thought the PRD project was about micro-lensing?

I wish that science reporters would stop setting up expectations regarding “earthlike planets”. Any data is good in an experiment. Scientists are not trying to find “Earth 2.0” as much as finding what is really out there. If they find an earthlike planet, then that’s just gravy.

@ Guillem- Is there any chance that astrometry could help here? Proxima is low mass, and the star is (of course) very close. Astrometry will be needed for the microlensing campaign…

As noted by the contributor Shellface at Extrasolar Visions II, there is a reference to a very marginal 5.6-day peak in the periodogram for Proxima Centauri in Anglada-Escudé & Butler (2012):

For comparison, I estimate that a planet receiving Earth-like levels of insolation would be at a period of about 8 days, neglecting details like Proxima Centauri being an active flare star. Not sure if this is the signal they’re aiming to confirm though.

Dear Guillem: Thank you for your answer! That is very exciting (even if still tentative) news! Fingers crossed from my part that it’s not magnetic activity. That would be such an important result, finding an Earth-like world at our door step… (I feel compelled to say: a Centauri Dream come true…) Still, from the period range you suggest, even if it is indeed a planet, there seems to be a distinct possibility that it will orbit beyond the HZ (P>15 days or so). In any case, all the best to you and your team, and I am looking forward to any publication or preprint.

A last thing I was wondering: given that the collaborating teams will be monitoring the brightness of Proxima – is this of relevance to the microlensing search? Are you sensitive to a potential observation, or is this restricted to Hubble?

Very excited to hear of this and a possible signal. As for observation period: that depends on how long the period of the habitable orbit is. Generally, three orbital periods of detected signal is sufficient. Two and a half months of observations is up to three orbits of a 25 day period or 10 periods of 7.5 days, so, plenty of time with a red dwarf of that size.

I was interested in astrometry and had asked Guillem a while ago . He kindly gave me a tutorial with respect to Gaia , best precision 8 microarc seconds (muas)

The equation that applies for finding a planet round a star is:

Precision= 3muas(planetary mass/star mass) x (orbital radius/stellar distance)

Where planetary mass =Earth masses and stellar mass= sun masses

,Orbital radius is in AUs and stellar distance in parsecs (3.25 light years )

So for a mass Earth planet in M5 Proxima’s habitable zone at say 0.05AU, with mass Proxima= 0.12 Sun and distance =1.3 parsecs ,that gives a required precision level of 0.8muas ! An order of magnitude out and very difficult to achieve as it requires incredible “thermomechanical” stability , exactly the same problem as with high contrast direct imaging ironically.

So though distance clearly helps , so does planetary mass and radius of orbit ( with bigger values helping unlike RV spectroscopy where the opposite applies )

The effects of the two microlensing events won’t be nearly enough unfortunately.

Drew or Guillem are welcome to explain how this is influenced in a close binary system , like for instance Alpha Centauri ,which is the next obvious question and might open up interesting avenues with Gaia.

@Ashley Baldwin: It is my understanding that there is actually a trend toward increasing planet frequency as stars get smaller just that the planets themselves tend to be smaller. I now remember reading that there are fewer super-Earths and mini-Neptune’s around M-stars, but that the frequency of Earth-size and sub-Earth size planets does not decrease from early to late red dwarfs. Based on this, it would be reasonable to suspect that both Barnard’s star and Proxima Centauri could have compact systems consisting of a few sub-Earth to Earth sized worlds after all. In fact, I would be surprised if neither one of these stars has terrestrial planets.

@ Guillem: May we take it to mean that because, based on the current data, you would have put Proxima in the ‘recycle bit and moved on’ to looking at other stars that you are not very confident that the aforementioned signal is indicative of a real planet? Also, I am confused though because you mentioned that the star is variable in the few hundred days whereas the candidate signal is much less than 100 days? Exciting times!

Lastly, does anyone know if there are instruments at least in the planning phase that could search via direct imaging for small planets around our nearest neighbors?

The only mission is STEP or SAIL a Chinese astrometry mission looking down at ten or less microarc seconds . Struggling with the thermomechanical difficulties aluded to and behind its 2020 launch. A 10m plus future UVOIR telescope with a suitable high performance coronagraph might get close which is under consideration by the 2020 Dedadel science and technology groups.

spaceman wrote: “Lastly, does anyone know if there are instruments at least in the planning phase that could search via direct imaging for small planets around our nearest neighbors?”

I can’t answer that question, but I have ruminated on a possible technique for directly imaging such exoplanets. The tiny, very dim white dwarf companion of Sirius (Sirius B, “the Pup”) was discovered by accident when a new telescope objective lens (made by Alvin Clark & Sons, if memory serves) that was under test was being sighted on the edge of a building, waiting for Sirius to come into view. Seconds before Sirius emerged from behind the occulting edge of the building, Sirius B appeared. Now:

One or more telescope-equipped robotic landers on the Moon could use our natural satellite’s slow rotation and its sharp, airless horizon to provide a similar “knife-edge” occulter. At least with exoplanets orbiting closer stars, it should be possible to spot them–and observe them for rather long periods–while their stars remain occulted just below the lunar horizon. Repeated observations (using one lander, or a series of them in turn, “strung out” along a line of lunar latitude), would enable the exoplanets’ apparent orbits to be plotted. (In the 1960s, Dr. Herbert Friedman of the U.S. Naval Observatory proposed setting up an X-Ray telescope on the floor of a crater on the Moon for this same occultation purpose [using the crater wall as the knife-edge occulter; an optical telescope could also use this arrangement], in order to determine the positions of optically invisible X-Ray “stars.”)

Paul Gilster: Check out the “Extrasolar Visions II” website at http://www.solar-flux.forumandco.com and click on Sirius-Alpha’s latest posts. This is apparently WHERE the earth-like planet rumer STARTED!

@J. Jason Wentworth

“One or more telescope-equipped robotic landers on the Moon could use our natural satellite’s slow rotation and its sharp, airless horizon to provide a similar “knife-edge” occulter.”

Fantastic idea. It seems as though another idea would be to erect a knife-edge, horizontal, thin strip, 360 degrees around the robotic scope at a suitable height above the horizon so the scope can see clear space under and over the strip… lining the rim of the aforementioned crater would be ideal. Then, the scope would be able to measure both post-ingress and pre-egress of the star just a short time apart to catch any exoplanets leading or trailing the star across the width of the knife-edge strip.

I’m looking forward to any results that come out of this Proxima campaign.

It’s great to hear that Proxima is finally getting some attention (including the February occultation).

I hope artists (and scientists, who should know better) stop portraying red dwarfs as being “red”. Unless it’s a very late M, brown dwarf or a carbon star, the typical M dwarf is going to be some shade of yellow.

Even Proxima’s light is bluer than an incandescent bulb.

ESO mentions a “10 to 30 day orbital period range”. Does this mean that there may be TWO planets in stead of JUST ONE?

Spaceman, pardon me . Quite right . Dressing and Charbonneau’s recent review of the Kepler catalogue does indeed show greater frequency for smaller and Earth sized planets (but not less than 0.7 Mearth so there may be many more smaller but still habitable planets to be found ) . It’s just Neptune size and above that are deficient . Good news for TESS is that there should be a habzone Earth mass planet transiting within 29 parsecs. Let’s hope it’s in the prolonged imaging /JWST sweet spot . Nearest non transiting habzone planet within 7 parsecs . Just 23 light years .

Ref: J. Jason Wentworth – Mark Zambelli

Interesting article on Aldebaran’s occultation by the moon:

http://strictlyastronomy.tumblr.com/post/137639523261/see-aldebarans-great-disappearing-act-tonight-in

The grazing occultation near the lunar south pole would work for picking up any exoplanets on either side of Aldebaran since it is only 65 light years away. Using several telescope with lucky imaging and even recordings from different amatuer astronomers could be combined to increase the number of photons via stacking. So what nearby stars will be occulted since the Moon can be up to about 5 degrees north or south of the ecliptic? What would be the distance the exoplanets could be in sub arcseconds from the list of nearby stars and could that be resolved or would the frame rate need to be increased to pick them up from background?

Pale Red Dot!!! :-)

Mark Zambelli wrote:

“Fantastic idea. It seems as though another idea would be to erect a knife-edge, horizontal, thin strip, 360 degrees around the robotic scope at a suitable height above the horizon so the scope can see clear space under and over the strip… lining the rim of the aforementioned crater would be ideal. Then, the scope would be able to measure both post-ingress and pre-egress of the star just a short time apart to catch any exoplanets leading or trailing the star across the width of the knife-edge strip.

“I’m looking forward to any results that come out of this Proxima campaign.”

Thank you. I too had thought about an artificial occulting strip, but even with 1960s-vintage technology, a crater rim–with its natural variations in height and contour–was considered more than adequate for use with a crater floor-based X-Ray telescope. (Dr. Herbert Friedman’s proposal was mentioned in Arthur C. Clarke’s 1968 book “The Promise of Space.” [Incidentally, I described his position incorrectly; Dr. Friedman worked at the U.S. Naval Research Laboratory].) Also:

The rim of a lunar crater, with its occasional apparent small “peaks” as seen from the crater floor, could also come in handy in case an exoplanet’s orbit plane was more-or-less parallel to the Moon’s horizon. A movable, vertical (or tilt-able) rectangular occulting shield could also be placed near a star’s rising point on the crater rim (a small robotic rover could carry and move the occulter as needed). Since a star would rise at a non-90 degree angle at lunar latitudes north or south of its equator, the vertically-oriented occulter could catch exoplanets at some elongations from the star, even if their orbit planes were parallel to the lunar horizon. In addition:

An lander-carried optical telescope that could resolve (relatively) nearby exoplanets in this way need not be large, and co-ordinating the images of two similar telescopes, landed (or placed by rovers) some distance apart (with separate occulters, if needed), would increase the system’s resolving power.

FrankH wrote (in part):

“I hope artists (and scientists, who should know better) stop portraying red dwarfs as being “red”. Unless it’s a very late M, brown dwarf or a carbon star, the typical M dwarf is going to be some shade of yellow…Even Proxima’s light is bluer than an incandescent bulb.”

There is–as strange as this sounds–an advantage to be had by depicting such red dwarf stars as red. James Nasmyth’s dramatic illustrations of jagged-edged lunar craters and lunar mountains were considerably different from those features’ actual forms (they do look jagged under the right lighting conditions, as I’ve seen), but they did–along with the Linne’ affair (regarding a small crater that supposedly disappeared)–serve to revive popular (and professional astronomical) interest in the Moon during the second half of the 19th century. Now:

As long as one is not “lying” by deliberately mis-representing a celestial body’s character (in other words, where uncertainty leaves latitude for artistic interpretation), making illustrations as exciting as possible, within the bounds of possibility, is not a bad thing. Such illustrations of solar system vistas (Chesley Bonestell’s and Ludek Pesek’s, in particular) hooked me as a youngster, and the reality was more than interesting enough that I was not disappointed by it.

@Ashley Baldwin: Well, it might be that the nearest non transiting habzone planet is actually no more than 4.3 light years away… I am sure Stephen Baxter and many of his fans would want to call this world “Per Ardua”… :) (if it exists, that is)

Harry R Ray wrote:

“ESO mentions a “10 to 30 day orbital period range”. Does this mean that there may be TWO planets in stead of JUST ONE?”

I can’t speak for them, of course, but I wonder that, too–and there is an attitude among many scientists (which isn’t unjustified) of *not* getting one’s hopes up for such bountiful discoveries, because (as they often say), “We’re seldom that lucky.” But such “My cup runneth over” discoveries have occurred in astronomy before: In 1877 Asaph Hall discovered Deimos orbiting Mars, and very soon afterward he spotted Phobos. A century later, an observation of an occultation of a star by Uranus revealed its ring system.

J Jason Wentworth: If it is ONLY ONE PLANET, they may announce as EARLY AS THIS SPRING! If it is TWO(or MORE:THREE could fit in orbits of 10, 20, and 30 days), they will ALMOST CERTAINLY WAIT until ESPRESSO is FULLY OPERATIONAL at the end of this year(if all goes well) to dig out ALL THE DETAILS of the system. I hope there ARE three planets, and that they call the OUTER one “Proxima Three” in HONOR of the Babylon 5″ TV series!

If they DO wait for ESPRESSO, we may have Pale Red Dot TWO EXACTLY ONE YEAR FROM NOW!

Regarding ESPRESSO, can anyone confirm its installation date of 7 February at Paranal?

http://obswww.unige.ch/Instruments/espresso/events/?event_id=70

Mike Fidler: Thank You for posting this link http://strictlyastronomy.tumblr.com/post/137639523261/see-aldebarans-great-disappearing-act-tonight-in ! This is an area (as Dr. Rupert Sheldrake advocates in his book “Seven Experiments That Could Change the World,” in which he explains that revolutionary discoveries are possible with very simple, inexpensive experiments) where existing telescopes and imagers, an ephemeris, the Moon, and a little patience could reveal the existence of numerous exoplanets. (Ole Roemer’s measurement of the speed of light–made using only a telescope, an ephemeris, a clock, a calendar, and Jupiter’s mutually-eclipsing satellites–is a similar example of a revolutionary discovery made on the cheap.) Also:

The limbs of the Moon have numerous irregularities (mountains, crater rims, walled plain ramparts, etc.) that could be used for grazing occultation observations to catch exoplanets whose orbit planes are more-or-less tangent to a limb section at the point of contact. Exoplanets whose orbit planes are more nearly parallel with the Moon’s direction of motion could be found via normal (non-grazing) occultations (either at immersion or emersion during the same occultation). This is a type of research in which stellar occultation observers, lunar observers, and those involved in astrometry (they could compute upcoming grazing occultations) could find many new extrasolar planets. The Moon doesn’t (if memory serves) occult the Alpha Centauri system, unfortunately, but there are several bright stars (such as Aldebaran) in the Zodiacal band which the Moon occults from time to time, and some of the relatively close but dim stars likely lie in that band as well.

Harry R Ray: While Proxima could turn out to be a “dry hole,” I will be delighted (and not surprised) if a future press release from the Pale Red Dot project says, “The Jupiter II has somewhere to go, after all…” :-)

Very interesting. The following very nearby red dwarf systems appear to be near the ecliptic and some of them might be therefore apt for occultations by the moon and other solar system bodies, and also I guess that potentially could be included and checked in Kepler/K2 campaigns: Wolf 359 (CN Leonis), Ross 154 (V1216 Sagittarii), DX Cancri, Ross 128 (FI Virginis), Luyten 789-6 (EZ Aquarii) Please someone more knowledgeable than me confirm this, and the latter point using http://keplerscience.arc.nasa.gov/K2/ToolsK2FOV.shtml

LET THE READER BEWARE! This is PURE speculation, but with a lot of PURE LOGIC behind it! A three-way race to the finish line, which will be crossed in late June? FIRST “RUNNER”: MOST(Kipping et al). 13 days of observation in the summer of 2014. Able to detect planets down to 0.8 Re(a ground based search able to detect planets down to 1.01 Re came uo with NOTHING!), AND: An ADDITIONAL 30 days of observing in 2015(pre-planned, or a FOLLOW UP? Anybody know?). Results to be revealed BY the summer(LATE June?). SECOND RUNNER: The Mesolensing event next month(can data reduction be completed in JUST FOUR MONTHS?). THIRD RUNNER: Pale Red Dot. If Kipping et al have a 3 sigma detection in the bag(very likely if the ADDITIONAL 30 days WAS a follow-up), the planet would have to be either 0.8 or 0.9 Re for the ground based search NOT to detect it.

This means RV detection would probably HAVE to wait for ESPRESSO. A STRONG mesolens signal could detect a planet that small as well. WHO WINS(if ANYBODY)?

Paul Gilster: Any UPDATE on the now COMPLETED microlensing or mesolensing event?

Still waiting on results — I have no further word.