A mission as complex as the European Space Agency’s highly successful Rosetta is a compilation of interlocking parts. I always find it fascinating to look at the instrumentation aboard. Take Alice, a UV imaging spectrograph no bigger than a shoebox. Alice weighs in at less than 4 kilograms and draws a meager 4 watts of power, but it offered us a thousand times the data we could retrieve with similar instruments no more than a generation ago.

Alice produced over 70,000 spectra in two years, according to its principal investigator, Alan Stern (a familiar name indeed for those interested in the outer Solar System!) With these data we’re learning about the porous surface of the comet, its lack of exposed water ice, and the unexpected occurrence of molecular hydrogen around it.

Rosetta’s Ion and Electron Spectrometer (IES), likewise the work of the Southwest Research Institute, is another triumph of miniaturization, achieving the sensitivity of instruments weighing five times as much (IES has a mass of about a kilogram). In combination with four other instruments analyzing the plasma environment, the IES examined solar wind interactions with the coma of Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko.

For the final images of the Rosetta mission, we leaned on the spacecraft’s OSIRIS wide-angle camera, which captured the scene just before Rosetta made its controlled impact onto the surface on September 30. As expected, the signal from the spacecraft was lost upon impact, but we still coaxed information on cometary gas, dust and plasma out of Rosetta as it descended. All told, 11 science instruments contributed to Rosetta’s abundant reservoir of data.

As with the upcoming end of Cassini’s mission, there is a certain poignancy in Rosetta’s final chapter, though as the comet heads toward the orbit of Jupiter, there would have been too little sunlight to power the mission. Ending its life on the comet it studied seems fitting.

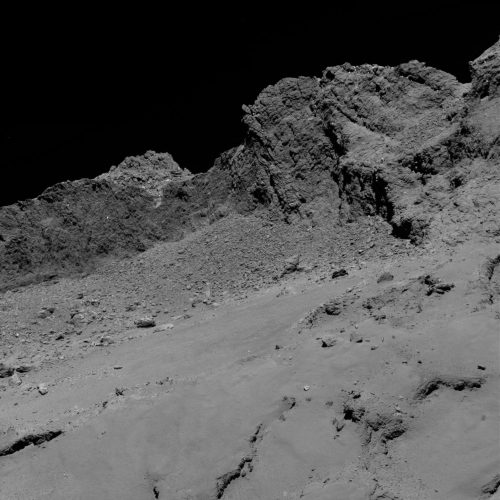

Image: The OSIRIS narrow-angle camera aboard the Space Agency’s Rosetta spacecraft captured this image of comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko on September 30, 2016, from an altitude of about 16 kilometers above the surface during the spacecraft’s controlled descent. The image scale is about 30 centimeters per pixel and the image itself measures about 614 meters across. Credit: ESA/Rosetta/MPS for OSIRIS Team MPS/UPD/LAM/IAA/SSO/INTA/UPM/DASP/IDA.

And here we have the final image, which reminds me in several ways of the final Huygens image from Titan. In both instances, we have a controlled descent to a surface of huge scientific interest culminating a first-of-its-kind mission, in Rosetta’s case the first spacecraft to orbit and escort a comet on its journey. I’m also reminded of some of the early images from the Moon, such as the photo Ranger 7 took at about 500 meters above Mare Cognitum in 1964.

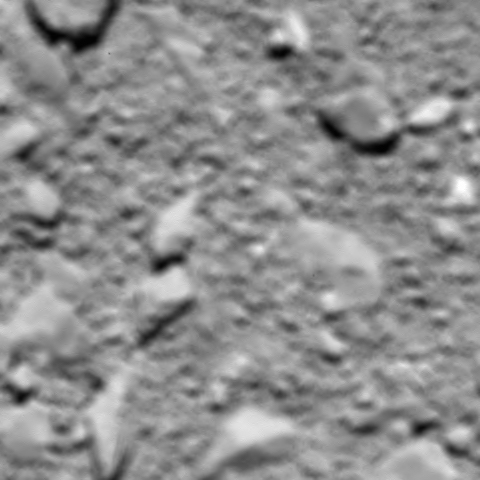

Image: Rosetta’s last image of Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko, taken shortly before impact, at an estimated altitude of 66 feet (20 meters) above the surface. The image was taken with the OSIRIS wide-angle camera on 30 September. The image scale is about 5 mm/pixel and the image measures about 2.4 m across. Credits: ESA/Rosetta/MPS for OSIRIS Team MPS/UPD/LAM/IAA/SSO/INTA/UPM/DASP/IDA.

Now, as with New Horizons, we have years worth of data to comb through, with early discoveries an indication of the richness of the datasets. The Rosetta Orbiter Spectrometer for Ion and Neutral Analysis (ROSINA) has demonstrated that comets contain the amino acid glycine, while discovering over 60 molecules at Comet 67P, 34 of which had never been found on a comet, according to André Bieler (University of Bern). Only some 5 percent of the ROSINA data has been analyzed to this point, which means we should have no shortage of future cometary analysis. We’ll also learn more from the Microwave Instrument for Rosetta Orbiter (MIRO) data, examining the behavior of gas and dust as they form the coma.

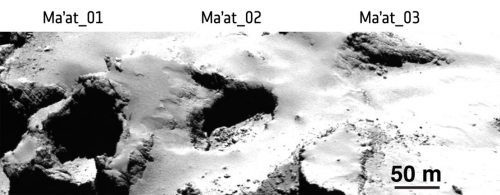

On the surface of Comet 67P is a 130-meter pit that mission controllers named Deir el-Medina. The reference is fascinating in itself. In the period of the Egyptian 18th to 20th dynasties (roughly 1550-1080 BC), Deir el-Medina (then known as Set Maat, or ‘Place of Truth’) was the village where artisans labored while they worked on the tombs in the Valley of the Kings. Painters and artisans decorated tombs dedicated to helping the spirit find its way in the afterlife.

Image: The region called Ma’at, on the smaller of the two lobes of Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko. Rosetta targeted a region that is home to several active pits measuring over 100 m wide and over 50 m deep, with the hope of getting some close-up glimpses of these features. The large, well-defined pit adjacent to the target site and identified in the image above as Ma’at 02 has now been named by the mission team ‘Deir el-Medina,’ after a pit in an ancient Egyptian town of the same name that was home to many of the workers who built the pharaoh tombs in the Valley of the Kings. Credit: ESA/Rosetta/MPS for OSIRIS Team MPS/UPD/LAM/IAA/SSO/INTA/UPM/DASP/IDA.

Cometary terrain adjacent to the Deir el-Medina region on Comet 67P is now Rosetta’s final resting place. The connection with an ancient village and key archaeological site is somehow fitting, as we connect our deepest impulses of exploration with our earliest attempts to probe the riddle of existence. The thought that human technology now rides a comet deep into the Solar System is a spur, goading us to reach out again, as we have so often done, into the unknown.

Some day researchers will be hunting down Rosetta for its valuable cargo: An etched disc containing over one thousand human languages:

http://rosettaproject.org/

http://sci.esa.int/rosetta/31242-rosetta-disk-goes-back-to-the-future/

I am a bit unsure if a comet is the best place to store human knowledge for future generations, but it is still likely better than just about anywhere on Earth.

Quoting from the main article:

“And here we have the final image, which reminds me in several ways of the final Huygens image from Titan. In both instances, we have a controlled descent to a surface of huge scientific interest culminating a first-of-its-kind mission, in Rosetta’s case the first spacecraft to orbit and escort a comet on its journey. I’m also reminded of some of the early images from the Moon, such as the photo Ranger 7 took at about 500 meters above Mare Cognitum in 1964.”

I was reminded of the last images of the planetoid Eros by NEAR Shoemaker, the Near Earth Asteroid Rendezvous space probe that explored it. Like Rosetta, NEAR was commanded to land on the “minor body” even though it was not strictly designed to do so. Unlike Rosetta, however, NEAR was not purposely shut off and the probe kept transmitting data for several weeks after touchdown in February of 2001.

This is the final image NEAR took of Eros just before landing:

http://nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov/planetary/mission/near/descent_images/near_descent_157417198.html

A collection of the NEAR descent images upon Eros:

http://nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov/planetary/mission/near/near_eros_descent.html

The official NEAR Web site:

http://near.jhuapl.edu/

Would not shutting off Rosetta really have caused problems? What more data could have been gathered by the probe being on the surface of the comet? I say this because NEAR did not keep transmitting forever and eventually the severe cold of space got to it. So perhaps Rosetta could have been kept on for as long as possible for extra science returns before space conditions rendered it inert.

A terrific mission!

how fast did it hit ??

At about walking speed for a human, according to reports I’ve read.

Combined with the comet’s incredibly low mass, easily survivable for Rosetta.

Here are the details FAQs from the ESA on why Rosetta was shut down rather than continue signalling from the comet’s surface as NEAR did on Eros in 2001:

http://www.esa.int/Our_Activities/Space_Science/Rosetta/Frequently_asked_questions

I still think they should have kept it functioning. We could have learned things from Rosetta’s unique perspective. As to those fears about its signal interfering with other deep space missions, since one of the reasons the probe was being shut off in the first place was due to it losing power as the comet headed out towards Jupiter’s solar orbit, Rosetta would not have likely not been transmitting indefinitely. NEAR eventually stopped signalling after a few weeks on its planetoid due to the deep cold of interplanetary space and I am sure this situation would have applied even more strongly with Rosetta.

The other reason I wanted ESA to keep Rosetta transmitting was to learn if it remained on the comet’s surface once it touched down. The probe carries that Rosetta Disc I linked to in this comments thread, which has over one thousand human languages which can be read with a suitable microscope. This will likely be invaluable to scholars in the future in terms of preserving human languages.

If Rosetta bounced off the comet back into space, we should know about this. And it is a possibility as Philae bounced a kilometer up from the surface after its harpoons failed to function (they were not tested before launch in 2004 due to a group of delegates arriving on that test day, I kid you not) and came close to escaping the comet itself.

Another reason to know if Rosetta is on the comet or not is that future explorers could see just how well or otherwise an artificial construct could survive on a comet, especially one that was not especially designed to be on such an alien surface.

In any event, a lost opportunity for some final unique science and confirmation that the probe is on the comet for future generations to find and learn from. Hopefully next time whoever sends a similar mission to a comet will be able to fill in these gaps for science and space exploration.

Here is the actual ESA FAQ on Rosetta’s comet landing and their reasons why they did not keep the probe transmitting after surface contact:

http://www.esa.int/Our_Activities/Space_Science/Rosetta/Rosetta_s_grand_finale_frequently_asked_questions

And no, they cannot turn Rosetta back on.

Great essay, Paul! In addition to the considerable advances made in the realm of instrument miniaturization, I also like to reflect on the long term ability of Rosetta and host of other probes to survive in the harsh environment that is outer space.

It is quite remarkable how Earth-like the first image is despite the almost non-existent gravity. Only a color image might suggest the view was not on Earth.

Everyone and everything has to have a theme song, am I right?

Albedo 0.06: Vangelis returns

The end of the Rosetta mission last week marked the beginning of something else: the release of a new album by composer Vangelis inspired by the comet mission. Dwayne Day examines the long-running links between Vangelis and other electronic music composers and spaceflight.

http://www.thespacereview.com/article/3072/1

To quote:

Earlier this year, the Cartoon Network aired an inspired bit of programming poking fun at electronic music and its penchant for seriousness and cosmic visions. Called Live at the Necropolis: Lords of Synth, it was an 11-minute film portrayed as a long-lost videotape recording from a 1986 public television program featuring an epic concert battle between three synthetic music legends: Xangelix (guess), Morgio Zoroger (i.e. Giorgio Moroder), and Carla Wendos (i.e. Wendy Carlos). They meet to compete to score the arrival of Halley’s Comet, with the winner being anointed “The Lord of Synth” and the losers being “banned from music for a period of one hundred years.” Xangelix is billed as “a reclusive genius who has appeared in public only… never.” Zoroger and Wendos are “former lovers,” which occurred sometime after Wendos transitioned from being a man. When the comet changes direction and heads towards Earth, the rival musicians must set aside their differences and battle it with their synthesizers, achieving a higher level of existence in the process. Xangelix is shown prophetically saying that “there is only one hope for humanity: the synthesizer.” (Not quite as good as Zoroger’s introduction: “a devil-may-care playboy who drinks a lot, even for an Italian.”) Like all great parodies, the writers had to love their subject to skewer it so effectively.

http://www.adultswim.com/videos/specials/live-at-the-necropolis-lords-of-synth/

“Humanizing” the Rosetta/Philae mission, for those who do not find exploring and landing upon a comet enough of an attention-getter:

https://thehighfrontier.wordpress.com/2016/10/11/rosetta-philae-its-all-about-the-feels/

Related subject article:

http://qz.com/774106/the-story-of-philae-the-little-robot-that-flew-across-the-solar-system-to-land-on-a-comet/

Avalanches, Not Internal Pressure, Cause Comet Nuclei Outbursts:

http://www.psi.edu/news/steckloffcomets

Western University astronomers predict possible birthplace of Rosetta-probed comet 67P:

http://mediarelations.uwo.ca/2016/10/17/western-university-astronomers-predict-possible-birthplace-rosetta-probed-comet-67p/

I hope the Rosetta disc is recovered before the comet comes apart:

https://www.sciencenews.org/article/comet-67p-cracking-under-pressure

Rosetta in the Rearview: What Have We Learned?

Posted by John Noonan

2016/11/07 21:26 UTC

Just over a month ago the European Space Agency’s Rosetta spacecraft finished its mission by spectacularly diving into Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko, the subject of roughly two years of ground-breaking observations at unprecedented distances. Rosetta’s instrument suite made hundreds of thousands of observations and satisfied the mission’s goals to better understand the origins and activity of the comet.

Now that the observing period has ended and all of the data returned to Earth via the Deep Space Network, scientists met at the recent American Astronomical Society Division of Planetary Sciences meeting in Pasadena, California to discuss these results and their implications for the field of planetary science as a whole. How did observations by Rosetta influence and alter our ideas about the typical formation and lifetime of a comet?

Full article here:

http://www.planetary.org/blogs/guest-blogs/2016/1107-rosetta-in-the-rearview.html

To quote:

The frozen time capsule from our early solar system that is 67P has provided the Rosetta team and the planetary science community with incredible data. The relatively pristine and primitive nucleus may have been altered recently, but it contains clues about the early protoplanetary disk. The revelations that the comet didn’t have any exposed water ice on the surface and that electron impact excitation proved to be an important mechanism in the near nucleus coma are unprecedented, and would not have happened without Rosetta’s uniquely close observations. The unexpected discovery of molecular oxygen provides an important clue about the collision history of the comet, with two possible methods of creating the double lobed structure without losing all of the easily sublimated volatiles like O2. Though the Rosetta mission has come to an end, the data from it will remain the best cometary data available to planetary scientists for years, as the next cometary mission hasn’t even been proposed yet. The issue with all asteroid and comet missions is that the sample size remains so small; out of the millions, if not billions of asteroids and comets we have only studied a handful. Rosetta’s instrument resolution and ability to escort the comet through its orbit are two incredible unique factors that must be replicated in the future to improve our understanding of these planetary fossils.

“Chury” is pretty young for a comet, perhaps a mere billion years old:

http://www.unibe.ch/news/media_news/media_relations_e/media_releases/2016_e/media_releases_2016/chury_is_much_younger_than_previously_thought/index_eng.html

Rosetta’s last words: science descending to a comet

ESA Blog

On 30 September 2016, at 11:19:37 UT in ESA’s mission control, Rosetta’s signal flat-lined, confirming that the spacecraft had completed its incredible mission on the surface of Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko some 40 minutes earlier and 720 million km from Earth. Rosetta was working up to the very end, collecting reams of science data as it descended towards a region of pits in the Ma’at region on the comet’s ‘head’.

Before we ‘retire’ the blog, we wanted to catch up with the instrument teams following this grand finale to find out how their instruments performed and if there were any surprises in Rosetta’s last ‘words’ from the comet.

Full article here:

http://blogs.esa.int/rosetta/2016/12/15/rosettas-last-words-science-descending-to-a-comet/

To quote:

“It’s great to have these first insights from Rosetta’s last set of data,” says Matt Taylor, ESA’s Rosetta project scientist. “Operations have been completed for over two months now, and the instrument teams are very much focused on analysing their huge datasets collected during Rosetta’s two-plus years at the comet.

“Data from this period will eventually be made available in our archives in the same way as all Rosetta data.”

A big thumbs up to the ESA for this very ambitious mission!

This is why we need space missions throughout the Sol system and beyond:

Shifting dunes found on Comet 67P courtesy of the Rosetta probe:

http://www2.cnrs.fr/en/2885.htm

Rosetta showed the importance of having an orbiter over a flyby mission:

21 March 2017

Growing fractures, collapsing cliffs, rolling boulders and moving material burying some features on the comet’s surface while exhuming others are among the remarkable changes documented during Rosetta’s mission.

A study published in Science today summarises the types of surface changes observed during Rosetta’s two years at Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko. Notable differences are seen before and after the comet’s most active period – perihelion – as it reached its closest point to the Sun along its orbit.

“Monitoring the comet continuously as it traversed the inner Solar System gave us an unprecedented insight not only into how comets change when they travel close to the Sun, but also how fast these changes take place,” says Ramy El-Maarry, study leader.

Full article here:

http://www.esa.int/Our_Activities/Space_Science/Rosetta/Before_and_after_unique_changes_spotted_on_Rosetta_s_comet