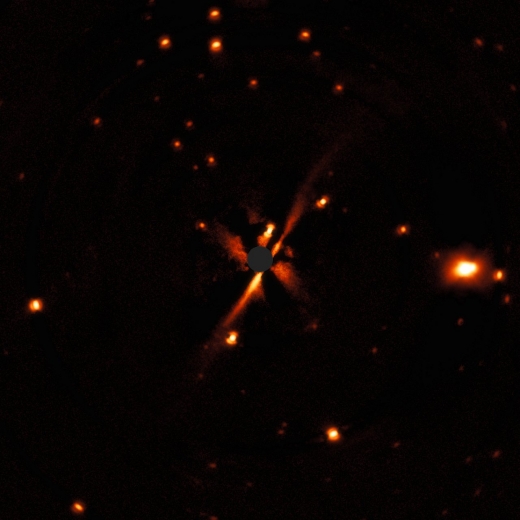

Here’s an interesting situation: Around a star designated GSC 07396-00759, a member of a multiple star system, astronomers have found an edge-on disk. Such disks are helpful ways of studying planetary evolution, as we’re looking at gas, dust and planetesimals that represent a planetary system in the process of formation. But at GSC 07396-00759, the disk is more evolved than the gas-rich disk around the T Tauri star in the same system. In other words, we have two stars evidently of the same age whose disks show a different evolutionary pace.

Elena Sissa (INAF-Osservatorio Astronomico di Padova) is lead author of a new paper on this find, in press at Astronomy & Astrophysics. The paper puts the matter this way:

Even if there is no “smoking gun” proof, the system characteristics all together tend to favor an evolved/debris disk nature for GSC 07396-00759 over a primordial/gas-rich disk. If confirmed, this is a very interesting discovery since this star and V4046 Sgr form a coeval physically bound system that would consist of a gas-rich circumbinary disk and a debris disk. Therefore it is of paramount importance to search for gas in the GSC 07396-00759 disk.

Image: This SPHERE observation is the discovery of an edge-on disk around the star GSC 07396-00759, which is a member of a multiple star system included in the DARTTS-S sample. Oddly, this new disk appears to be more evolved than the gas-rich disk around the T Tauri star in the same system, although they are the same age. The disk extends from the lower-left to the upper-right and the central grey region shows where the star was masked out. Credit: ESO/E. Sissa et al.

Such finds highlight the reasons we study disks in the first place, to learn more about how planetary systems emerge. And we’re now getting new images from the SPHERE instrument mounted on the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope in Chile that show us discs in more detail than ever before. SPHERE stands for Spectro-Polarimetric High-contrast Exoplanet REsearch instrument, a planet finder whose primary job is to do direct imaging of gas giants around nearby stars, but one that’s also fine-tuned for turning up protoplanetary disks.

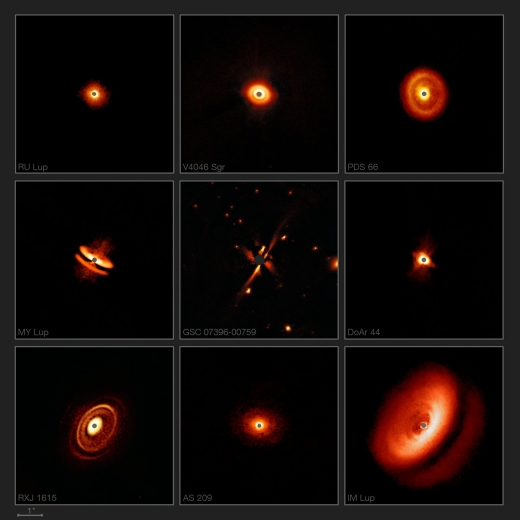

In the image below, we’re looking at T Tauri stars, which are less than 10 million years old and varying in brightness. Our early Solar System may well have looked something like the disks we see here. A survey called the DARTTS-S (Discs ARound T Tauri Stars with SPHERE) produced most of this work, though the GSC 07396-00759 find came from a different survey effort; both used SPHERE to produce their images. The targets are all relatively near, ranging from 230 to 550 light years from Earth.

Image: New images from the SPHERE instrument on ESO’s Very Large Telescope are revealing the dusty discs surrounding nearby young stars in greater detail than previously achieved. They show a bizarre variety of shapes, sizes and structures, including the likely effects of planets still in the process of forming. Credit: ESO/H. Avenhaus et al./E. Sissa et al./DARTT-S and SHINE collaborations.

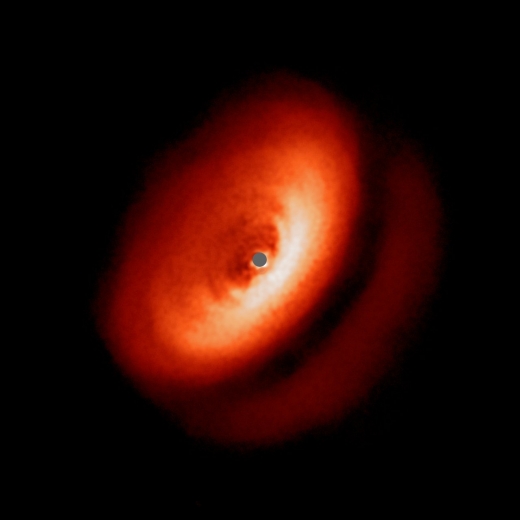

The SPHERE imagery also takes in a target previously investigated by the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), which found two rings of material within the disk surrounding the Sun-like star IM Lupi. Both rings are made up of heavy ions in the form of DCO+ (deuterium, carbon, oxygen). Here I turn for background to work by Karin Öberg (Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics) and colleagues, who studied the IM Lupi disk’s chemistry and published a 2015 paper on the matter. Says Öberg:

“With ALMA we can directly observe this chemistry in discs that are right now in the process of making planets. The molecules have formed two spectacular rings. The inner one we expect to see; the outer one comes as a complete surprise and sheds new light onto the properties of a protoplanetary disc’s outer reaches.”

For more on this unusual disk, see Surprising chemistry seen in molecular rings around young star, an article in Astronomy Now. SPHERE now offers IM Lupi’s unusual disk in striking detail.

Image: This spectacular image from the SPHERE instrument on ESO’s Very Large Telescope shows the dusty disk around the young star IM Lupi in finer detail than ever before. Credit: ESO/H. Avenhaus et al./DARTT-S collaboration.

The images of T Tauri star disks were presented in a paper entitled “Disks Around T Tauri Stars With SPHERE (DARTTS-S) I: SPHERE / IRDIS Polarimetric Imaging of 8 Prominent T Tauri Disks”, by H. Avenhaus et al., to appear in in the Astrophysical Journal (preprint). The discovery of the edge-on disk is reported in a paper entitled “A new disk discovered with VLT/SPHERE around the M star GSC 07396-00759”, by E. Sissa et al., to appear in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics (preprint).

I am interested in the dark band around the midsection, it indicates cool dust and gas. Does this cool band cause the frost/snow line to move in much more than before. It may have implications with Ceres in our solar system, which appears to have an outer solar system composition contrasting with its current location.

I think the dark band in the middle is from too much material so no light get out.

My interest is more in the faint rings close in, that suggest planets in formation.

Fascinating… Those images certainly make me dream…

I wonder if these planetary disks are being analyzed for their phosphorus content. They should be. How hard can that be? What question could be more relevant, given our interest in the question “how common is life in the universe”. Recently a question of phosphorus has been raised with regard to remnant dust clouds from super novae. Verification or refutation should be sought in these planetary disks. http://www.livescience.com/62248-extraterrestrial-life-phosphorus.html

An interesting paper about the nitrogen cycle in Pluto and the formation of Sputnik Planitia: https://arxiv.org/abs/1804.02434

I wonder if such disks would be suitable for colonization? A bit premature, I suppose, given their distance.

By the time we get there, there will be solid planets.

It’s only a couple hundred light years, humans could, plausibly, be there in a few thousand years, without breaking, or even scuffing up, any laws of physics.