Centauri Dreams’ resident movie critic turns his attention to a personal favorite from the canon of science fiction films. My own memories of The Thing from Another World go back to late Saturday night black-and-white TV, where I first saw the chilling tale as a boy. The scene where the team fans out on the ice as they try to figure out what it is that is frozen down there still puts a chill down my spine. Who knew at the time that The Thing himself was James Arness, early in his career arc toward Gunsmoke’s Matt Dillon? Larry gives us all the details, including reflections on the film’s significance in its time and the questions it raises about our attitudes toward the unknown. Don’t be surprised to find a collection of Larry’s Centauri Dreams essays making its way into book form one of these days.

by Larry Klaes

Ah, aliens. For some humans, they are the conquering interstellar warriors of some tyrannical Galactic Empire. To others, they are angelic saviors just waiting to uplift humanity into the wider Cosmos. To still more, they are aloof godlike beings who are completely indifferent to anyone unlike themselves. If an alien happens to be a member of the Star Trek franchise, the chances are very good they will look, talk, and act very much like a certain primate species of the planet Sol 3 (a.k.a. Earth), with perhaps some variations to the ears and nose.

In many science fiction stories dealing with extraterrestrial intelligences (ETIs), aliens can be all four of the types mentioned above. However, just as often our imagined cosmic neighbors can and do become little more than outright monsters: Creatures of the Id aimed at our basest fears who exist only to maim, extinguish, and sometimes consume unwary victims – while giving audiences visceral thrills designed to voluntarily release portions of their currency to these story makers multiple times.

This last category became the standout feature of many science fiction films, hitting their stride in the 1950s. The results range from great in a few notable cases down to quality levels that were found wanting for the majority of the rest.

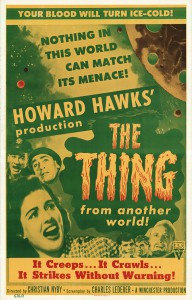

One of the earliest and most memorable standouts of this genre from the mid-Twentieth Century was the science fiction/horror film titled The Thing from Another World (often referred to as just The Thing), Produced by the Winchester Pictures Corporation and released by RKO Radio Pictures, it premiered on April 27, 1951.

Given a cursory look, the main plot and overall trappings of this cinematic experience called The Thing can give one the impression of this motion picture being a standard, albeit classic, “monster movie.”

Or so it might seem…

Members of the United States Air Force (USAF) stationed at an air base in Anchorage, Alaska, are ordered to investigate a report by scientists at a remote Arctic research station of a possibly unusual aircraft that has crash-landed near the North Pole. Speculation on the craft’s identity ranges from the Canadians to the Russians, with the latter described as being “all over the pole like flies.” This is during the first decade of the Cold War, after all.

Image: The original film poster for The Thing from Another World.

The team of military airmen, the lead scientist of the research station, and a nosy journalist who is eager for a juicy story fly together to the reported crash site: They come upon not the expected terrestrial airplane in need of rescue, but instead a saucer-shaped alien spacecraft frozen in the Arctic wasteland! As the team attempts to remove the extraterrestrial vessel buried in the ice using thermite bombs, they accidentally destroy the entire ship in the process. However, the body of a lone occupant from the craft is found nearby, frozen in the ice.

The rescue/expedition team flies with their invaluable “prize” to the science research station just ahead of an approaching blizzard. There they crudely quarantine their confined “visitor”, only to have the alien being accidentally revived from its ice prison (by an electric blanket left on, no less).

Surprising the single guard on duty, the sentry uses his gun to shoot the alien multiple times, but without noticeable effect. The being subsequently escapes and proceeds to go on a rampage, injuring and killing both men and several of the station’s sled dogs.

Despite the creature’s violent and deadly behavior, which includes procuring the blood of its victims for both food and reproduction, the resident chief scientist perceives the alien as a highly evolved and therefore wiser and better being than his fellow humans: After all, this extraterrestrial life form arrived in a starship.

The scientist explains the alien’s hostile actions as a defensive response to its treatment by the equally hostile “alien” creatures from the station, along with their unwillingness to truly communicate with it. In stark contrast, the military personnel naturally and not without reason see this “thing” from outer space as a dangerous monster that threatens all their lives and possibly every other organism on Earth!

After attempting and failing to kill the alien intruder with bullets and fire, the airmen have one last plan to stop the creature before they are either slaughtered by the alien or freeze to death, as the alien has sabotaged the station’s furnaces. Their hope is to trap the alien in the generator room, where the humans are making their last stand, and electrocute the creature with a contraption rigged up along the floor.

Just as the alien enters the trap area, the lead scientist breaks ranks and rushes right up to the being, where he attempts to plead directly with the alien in order to reason with it to save its life so that the alien may in turn share its presumably superior knowledge and wisdom with humanity. The being responds by harshly knocking the scientist aside and continuing after the airmen.

The creature does step into the trap, where it is brutally electrocuted to the point of disintegration: The station and the world are saved by the menace from beyond the stars by a bunch of modern-day warriors wearing leather bomber jackets underneath their parkas.

Later on, having a news “scoop” beyond his wildest dreams, the reporter relays the events of the last two days to his very eager listeners. Ready to plunge in with the details, the reporter first gives his audience (and by proxy the film’s viewers) this warning and plea:

“Every one of you listening to my voice… tell the world. Tell this to everybody wherever they are: Watch the skies everywhere. Keep looking. Keep watching the skies!”

Roll credits.

Let us first acknowledge what should be the obvious: That The Thing is a film with a story and characters written by and for human beings of the planet Earth; in particular, American human beings from the mid-Twentieth Century in the midst of the Cold War era who were also in the thick of dealing with anti-communist “witch hunts”.

There was also a particular mindset in terms of social conventions at the time of how men and women should be and behave, especially towards anything that was different, even in ways that did not have to be literally alien to trigger certain responses.

The alien visitor in this story could have been friendly, or at least non-hostile, without sacrificing dramatic suspense and excitement in the process. This is what took place in the contemporary science fiction film It Came from Outer Space, released in 1953: The ETI in this story were also the victims of a spaceship that crashes on Earth, yet their only intentions were to repair their vessel and return to the stars. These aliens were explorers, not conquerors. They even informed the main human character, who happens to be an astronomer, that the two species were not yet ready to meet peacefully, for it was humanity which had a lot of maturing to do.

The aliens’ take on the situation was reinforced by the fact that an angry, armed mob of humans had been coming to destroy them, certain that these uninvited “guests” from outer space had only hostile intentions for the native terrestrials. Granted, the aliens had temporarily “possessed” certain townsfolk, which made them act unusual in the process, but this was only done in order to provide camouflage so that the distant voyagers could obtain the repair tools they needed in the nearby desert community as unobtrusively as possible. Had the aliens revealed their true physical appearance to the humans, they would have automatically terrified the local populace and created an even more immediate hostile response.

The resident scientist in It Came from Outer Space had been successful in quelling the mob from destroying the aliens in his story. The astronomer even kept the ETI from killing the humans that threatened them, which they reluctantly intended to do rather than be either captured or exterminated by these comparatively primitive and savage creatures.

This was not to be in the case with the “thing” in The Thing. The deck was stacked against this alien almost from the start. The very title of the film calls the alien a “thing”, even though the lead scientist, Dr. Arthur Carrington, emphasizes repeatedly the fact that the being came to Earth in a starship from another part of the Milky Way galaxy, stating that it therefore must possess at least some superior knowledge and wisdom (the alien is even dressed in a “civilized” fashion, wearing some type of manufactured coverall uniform).

Even the 1938 short story written by John W. Campbell, Jr., that The Thing is based on was titled “Who Goes There?” and the alien in that version was far more hideous, manipulative, and deadly to the trapped men of the Antarctic research station than the one of the 1951 film (the alien in the 1938 story was referred to only as the Thing, though).

The original cinematic plans for the physical appearance of the alien were more monstrous than the result that eventually arrived in the final film version. In a screenplay draft dated August 29, 1950, the first clear sight of the alien is described this way:

“He switches on his flashlight, and centers its beam on the ice-block. As Ericson said, the ice is now almost transparent. Through it, only partially distorted, can be seen an unearthly horror. It has a bulbous head, a tiny suck-hole for a mouth, multiple eyes, no ears. Its arms are extra-long, ending in thorny clusters, rather than hands. It stares malevolently through the ice.”

Despite this and other ambitious and creative concepts developed during production of The Thing, the filmmakers had neither the special effects technology nor the budget to make the alien look both so elaborate and convincing on screen. They finally settled on a being that bore more than a passing resemblance to the famous “monster” created by Victor Frankenstein in what is considered to be one of the first modern science fiction novels: Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus, written by English author Mary Shelley (1797-1851) and first published in 1818.

Specifically, the alien bears definite similarities to the version which most people identify with Frankenstein’s creation, the one made for the iconic Universal Studios film, Frankenstein, released in 1931 and played by actor Boris Karloff.

This decision, intentional or otherwise, has its own allusions to our discussion theme. In the original Shelley novel, the “monster” was actually intelligent, articulate, and feeling. He only became hostile and murderous after relentless negative encounters with human beings who were frightened by his appearance. A similar situation took place with Frankenstein’s creation in the 1931 film (and initial sequels), although here the “creature” was portrayed as being less intelligent and verbose, though no less feeling. In fact, had the makers of this landmark horror film gotten their way, the “monster” would have been reduced to a purely instinctual killing machine, all for the sake of entertainment.

Image: Actor James Arness portraying the title character. Note the more than casual resemblance to the cinematic Frankenstein monster, and not just due to film production budget and contemporary FX technology restraints.

Nature versus Nurture, or You’ve Got to be Taught to Hate

As the alien was not terribly big on civilly “dishing” about itself during the film, the hapless humans trapped with it (and by proxy, the viewing audience) often had to make their own assumptions regarding the nature of their uninvited guest from the stars and its true intentions. Naturally human biases, instincts, training, and educational backgrounds play a big role in the numerous assumptions and reactions. This includes the thoughts and intentions of the script writers, both subconscious and conscious.

A big part of these guesses involve whether the alien was provoked into its hostile reactions, or did it indeed intentionally come to Earth to introduce its species as the new dominant life form for our planet. We know for a fact that the humans were already splitting off into their own camps of thought from the moment they realized that the craft which crashed in the Arctic was no terrestrial airplane, not even something exotic from their chief Cold War rival.

Image: The airmen and scientists discuss what to do with their unexpected visitor trapped in the ice – but soon their “guest” will force their hands in the matter.

When they found the alien in the ice and brought it back to the research station, the enlisted military men who were assigned to guard it repeatedly told the others how uncomfortable they felt just being near the creature, even though at first everyone assumed it was dead. This instinctual reaction led one of the sentinels to place an active electric blanket over the ice block containing the alien so he would not have to look at it – or have the being look back at him, which he swore it was doing. This event caused the frozen chunk of water to melt and subsequently release the alien – which turned out to be very much alive!

One item before we continue: It was stated in the Internet Movie Database (IMDB) Goofs section for The Thing that the heat from a working electric blanket placed directly upon a large amount of ice would produce a lot of liquid water, enough to short out the blanket early on. Of course the plot required an unintentional reason for the alien to be released and active, since the USAF officer in charge, Captain Patrick Hendry, refused to have the alien removed from the ice block for any reason until he heard back from his superiors for further instructions.

One wonders what might have happened if the alien had not only been placed under more competent security, but included being monitored by the station scientists? They were in a civilian scientific research station, after all, not a military base. Instead, the being was placed in an unheated store room (a window pane was broken to make the room even colder from the outside air) and watched by shifts of lower ranking airmen – men who were trained to respond to unknowns either defensively or offensively and only follow orders.

While certainly none of the humans in this story had ever encountered an actual alien being before, these members of the warrior class were probably the least advisable people to have watch over such a life form in such a situation (and why just one person at a time, for that matter?).

When the alien did become free of its ice prison, the first reaction from the guard was to shoot it with his gun, six times in fact. We later discover that the bullets had no lasting effect on the alien, at least in the physical sense. Soon after, as the being was attempting to escape from the station, it was set upon by three of the sled dogs. The alien also survived that encounter (and killed two of the dogs outright in the process, while injuring the third badly enough that it had to be put down on the spot), but it lost an arm during the attack. No doubt by that time, if the being had any thoughts of the natives of this planet being friendly or at least non-hostile, they were utterly extinguished.

Of course the audience already “knows” that the alien is going to react negatively towards any and all terrestrial life forms it encounters. Not only is it called The Thing in the film’s title (as opposed to, say, E.T. The Extraterrestrial, like that friendly and adorable little alien in the 1982 film co-produced by Steven Spielberg), we are told and shown in various ways via the 1951 film’s trailer and marque posters that we are going to see a horror flick. The Thing is not a balanced, scientific documentary on the subject of ETI thinking, behaviors, and intentions.

Despite being quite humanoid in appearance, the alien in The Thing is revealed to be even less like a human or even what most humans consider to be a “higher” life form: When the scientists analyze the arm ripped off the alien during its battle with the sled dogs, they discover it is composed of material more like a plant than an animal.

The mammalian humans present are clearly not easily able to wrap their minds around the idea of a thinking, walking plant in general, let alone one that can build and fly a starship. This combination of ignorance, fear, and bias only makes the extraterrestrial being even more alien to most of the station residents, heightening their concerns about their “guest”.

The reporter, Ned “Scotty” Scott, and Dr. Carrington have the following conversation during this revelation, which leads to one of the most infamous lines in the film:

Scotty: “Please, doctor, I’ve got to ask this. It sounds like, well… Just as though you’re describing some form of super carrot.”

Dr. Carrington: “That’s nearly right, Mr. Scott. This carrot, as you call it, has constructed an aircraft [!] capable of flying millions [!] of miles, propelled by a force as yet unknown to us.”

Scotty: “An intellectual carrot. The mind boggles.”

Dr. Carrington: “It shouldn’t. Imagine how strange it would have seemed during the Pliocene [!] age to forecast that worms, fish, lizards that crawled over the Earth would evolve into us. On the planet from which our visitor came, vegetable life underwent an evolution similar to that of our own animal life, which would account for the superiority of its brain. Its development was not handicapped by emotional or sexual factors.”

When the reporter tells the scientist that his readers would likely consider the notion of an “intellectual carrot” as too wild to be taken seriously, Dr. Carrington counters this attitude by asking one of his colleague to give several examples of real terrestrial plant species: One type, the acanthus century plant, can capture and consume a variety of small animals. The other flora mentioned is the telegraph vine, which is aptly named, as it can send signals to other members of its species many miles apart.

“Intelligence in plants and vegetables is an old story, Mr. Scott. Older even than the animal arrogance that has overlooked it.”

Dr. Carrington’s fascination and unabashed admiration for the alien only grows when they discover that the being reproduces by creating seed pods from its body:

“Yes. The neat and unconfused reproductive technique of vegetation. No pain or pleasure as we know it. No emotions. Our superior. Our superior in every way.

“Gentlemen, do you realize what we’ve found? A being from another world as different from us as one pole from the other. If we can only communicate with it, we can learn secrets that have been hidden from mankind since the beginning.”

Dr. Carrington betrays his own biases here. While he is likely the only human at the research station who does not want the alien either dead or at least sent somewhere very far away from them, the scientist also assumes that just because the being came to Earth in a technologically advanced spaceship, it is therefore morally and ethically superior as well, if such concepts can be applied to a species that evolved in a different manner on another world in another solar system.

The film also betrays its own stereotypical views when it comes to scientists: Dr. Carrington is deeply impressed, bordering on envy, over how the alien makes copies of itself. Since it does not involve sexual reproduction and all the “complicated” (read messy) physical and psychological baggage that process tends to bring, at least for higher intelligence species like humans, Dr. Carrington sees the alien’s method as essentially unemotional and therefore superior. This goes along with his character’s devotion to Science with a capital S and not the more mundane pursuits and behaviors most non-scientific human beings focus their lives on – like the airmen.

The film assumes a man like Dr. Carrington will be passionate about science but otherwise unemotional and certainly not one to have physical feelings – behaviors we witness all too well between Captain Hendry and Nikki Nicholson, Dr. Carrington’s secretary. This almost makes him the human equivalent of the alien: Mentally superior, highly intelligent, aloof, and therefore potentially just as much a threat to the station and beyond as the alien, since Dr. Carrington seems more than willing to sacrifice all their lives in his single-minded pursuit of what he sees as a much higher and therefore better life form.

As the cinematic representative of Science and its practitioners, this stereotype is no fairer to the field and its professionals than the automatic assumption that a being from the stars is on Earth only for conquest and destruction rather than exploration and contact. This also goes for the film’s representation of the Air Force men, who are portrayed as being much more average in intelligence and far more interested in the baser pleasures of life that Dr. Carrington undoubtedly disdains. Their baseness includes the almost instinctual response to anything unknown with lethal force, especially an actual alien.

Even when the airmen were first on their way to investigate the crashed flying craft, which they knew almost nothing about before finding it, their general consensus was that the vehicle was probably of Soviet origin. For Americans of the early Cold War era, this could mean little else than a potential threat to their nation, whether it was a spy plane or something more elaborate like an experimental weapon. Worse, the airmen generally tended to blend into one another in terms of having any prominent individual characteristics.

Image: Our predetermined heroes on their way to meet their destinies near the North Pole.

In essence, everyone in The Thing is one level of stereotype or another, including the character of the film’s title. While this may be expected from Hollywood cinema, especially back in the day to use a phrase, it does have ramifications in terms of making audiences think certain ways, even if it is just reinforcing their already preconceived notions about certain types of people and concepts. Thus Science is represented by a man who is devoted to it and little else, be it biological urges or his fellow humans.

Oh, Dr. Carrington is constantly emphasizing how he wants the presumably superior knowledge of their visitor from the stars for all of humanity, yet he is not unwilling to endanger the lives of all the humans at the research station in order to communicate with the alien, including his own.

Dr. Carrington said the following declaration in the 1950 script draft, which was retained in a watered-down version of the final released film:

“Two of our colleagues have died and a third is dying. Those are our losses – and the battle has only begun. There will be more losses. The creature X is more powerful, more intelligent than us. We are infants beside him. He regards us as soft, vulnerable earth worms important only for his nourishment. He has the same attitude toward us as we have toward a field of cabbages.

“A new world has come to devour us. Only science can conquer it. Our minds, gentlemen – the little muscle that thinks, observes, examines and finds answers. All other weapons will be powerless.”

We get to the core of the filmmakers’ take on science as an amoral force in pursuit of its own agenda at the sake of all others during the following scenes when it is learned that Dr. Carrington is secretly growing the seed pods from the alien in the station’s greenhouse.

We observe more indications of the airmen’s views on science as amoral or at least indifferent to the safety and concerns of the wider world with this next bit of dialog from the 1950 film script draft. These scenes contain some extra useful details that did not survive into the released film, yet neither detract from nor drastically change what was shown on screen.

Dr. Carrington: “A secret has come to us, greater than any secret ever revealed to science. It must not be destroyed! It must be studied – and learned.”

Captain Patrick Henry (later changed to Hendry): “I saw it, Carrington. It’s not something to put under glass – and examine. And there are thousands more of them hatching. They’ll reproduce like weeds. They’ll tear the world apart.”

Dr. Carrington: “That doesn’t matter!”

Henry: “It kind of matters to me.”

Dr. Carrington: “Knowledge is more important than life, Captain. We have only one excuse for existing – to think, to find out, to learn what is unknown.”

Lt. Eddie Dykes: “We haven’t a chance to learn anything from that pookey Martian, except a quicker way to die, Doctor.”

Henry: “I’m ordering you back, Carrington.”

Dr. Carrington: “It doesn’t matter what happens to us! We’re not animals. We’re a brain that thinks! Nothing else counts, except our thinking. We’ve thought our way into nature. We’ve split the atom – ”

Dykes: “Yeah, and that sure made the world happy, didn’t it!”

[Stage direction] The mewing [of the newborn aliens raised in the greenhouse] out of the wall speaker increases.

Henry: “I’ve ordered you out, Carrington.”

Dr. Carrington: “We owe it to the brain of our species to stand here and die without destroying a source of wisdom! Captain, I beseech you. Science, government, the Army – civilization has given us orders.”

Henry: “They’re wrong order[s]. They come from people who don’t know what they’re talking about.”

Reporter Skeely (later renamed Ned “Scotty” Scott): “I’m with you there, Henry. In a pinch I always put my money on a little man – against all top brass.”

Dr. Carrington: “You set yourself above all human progress, above all science!”

Henry: “I set myself against an enemy, Carrington.”

MacAuliff: “Come on, Doctor. You’ve said your piece. This is one time when science doesn’t blow up the world… just to see what makes it tick.”

Note in particular the mention by Dr. Carrington about splitting the atom as one of science’s greatest achievements and the airmen’s reactions to it. The two sides were juxtaposing the benefits of atomic energy for running our technological civilization against the destructive reality of the atomic bomb. This latter item was often viewed by the general populace as a creation by science without either thought or safeguards as to whether or not it should be made – even though nuclear weapons came into existence in the United States at the demands of the government for the military: First to force the Axis powers of World War Two to surrender (and simultaneously beat them at developing such a weapon before the Allies could) and then to “balance” geopolitical power with the Soviet Union and their Iron Curtain allies.

There was also a quick comment early on in the film that Dr. Carrington is “the fellow who was at Bikini.” This is a reference to Bikini Atoll in the Pacific Ocean, which was used for conducting multiple nuclear bomb tests from 1946 to 1958. The atoll was left uninhabitable for humans due to the excessive amounts of radiation from these tests. Some of its numerous islands were outright obliterated from the powerful nuclear explosions.

These tests were performed as a major aspect of the Cold War: The nuclear weapons were, ironically, created and meant to prevent yet another global-scale war by making the possibility of a nuclear attack so devastating to Earth as to be untenable to any rational and ethical person or nation.

That the Thing looks so similar to Frankenstein’s monster as mentioned earlier only adds to the perception of science as an amoral force that delves into areas beyond where humans are considered capable of understanding or meant to be there. While the initial reasons for the alien ultimately resembling the Universal Studios film version of Mary Shelley’s monster were both technical and financial, the underlying message taken from it may have been consciously taken advantage of once the filmmakers saw the end result.

Both sides in The Thing have their points in their takes on the alien: The military men were already afraid of this being from another world even when it was presumed dead and encased in the Arctic ice when they first discovered it. That it came from another world in a vessel with unknown technologies and therefore abilities (including the underlying possibility of carrying weaponry with a similar bent) were reasons enough for them to be on alert for the worst possible scenarios of this unexpected and largely unplanned for situation. When the alien turned out to be very much alive and became free of its ice prison, their fears became confirmed and they immediately and instinctively went into warrior mode.

Dr. Carrington pointed all this out to Captain Hendry:

“Captain, when you find what you’re looking for, remember it’s a stranger in a strange land. The only crimes were those committed against it. It woke from a block of ice, was attacked by dogs and shot by a frightened man. All I want is to communicate with it.”

Captain Hendry: “Fine, provided it’s locked up.”

Of course we already know the deck is stacked against the alien being benevolent or even neutral, which makes the pleas and plans by Dr. Carrington seem naive at best and just as dangerous as a direct assault on everyone there at worst. However, it is not the scientist’s fault that he is unaware of what the filmmakers had in store for their characters.

It seems a bit much for such an intelligent man, no matter how excited he may be about coming upon what would be considered the most important scientific discovery in human history, responding to Hendry’s warning that the alien’s progeny will “reproduce like weeds” and “tear the world apart” by exclaiming “that doesn’t matter!” Unless Dr. Carrington’s illogical outburst was a combination of disdain for the Captain’s much lower level of scientific knowledge and words borne from exhaustion and an anxiousness not to lose such a unique intellectual prize. Nevertheless, it is still both excessive and irrational, especially if Dr. Carrington wants to reveal the supposedly superior wisdom and technology of the alien to the whole of the human race for their benefit. Getting his entire species wiped out in the process would rather defeat the purpose.

I think it is safe to say that Dr. Carrington’s personality is one that does not contain any serious levels of sadism, masochism, or megalomania. He has an obvious ego, of course, but this is borne of multiple earned achievements from a life-long career in science, including the Nobel Prize. As a further indication of Dr. Carrington’s overall character, it is interesting to note that someone of his stature and renown is still out working in the field – in the remote Arctic, no less – rather than a much more comfortable and perhaps even more profitable academia equivalent of a desk job, or in the corporate world, or even with the military, for that matter. His devotion to science is, if nothing else, certainly not for show but a genuine passion.

The words put into Dr. Carrington’s mouth by the scriptwriters show their biases on science and its practitioners in general. This reveals a genuine real world fear of what they don’t quite understand. In an ironic but hardly unexpected contrast for the era, the filmmakers turn to and lionize the ones whose main tasks are to monitor the region for (usually) terrestrial threats and to deal destruction and death when the situation calls for it – or even when told not to take the offensive in the particular case of this film.

These “regular Joes” are the kind our popular culture likes to measure by the “test” of who you would want to have a beer with. Whether you would want to drink beer or any other kind of liquid with either these airmen or Dr. Carrington and his cadre of scientists depends upon what kind of conversation topics and activities you prefer.

The other social hierarchy test portrayed in The Thing is who would prefer whom as a relationship partner. As the film takes place in late 1950, this naturally involves the designated Alpha Male (Captain Hendry) and the most prominent woman in the film, in this case Nikki Nicholson, who as a “bonus” happens to be Dr. Carrington’s secretary in terms of adding an extra layer of dramatic tension. Whole scenes are dedicated to establishing that the two have a form of romantic past together and will definitely upgrade to a serious relationship in the near future once this annoying ordeal with the asexually reproducing alien menace is over.

Ms. Nicholson shows definite signs of sympathy and respect for her work boss, as she constantly has to remind an increasingly frustrated Hendry that Dr. Carrington’s continually stubborn and life-threatening actions are due to his being both overexcited by the presence of an actual living ETI and very tired from lack of sleep over this major scientific discovery. However, in standard Hollywood tradition, it is made quite clear who is going to end up with whom by the time the film credits roll, though the scientist shows no non-work-related interest in Nikki or anyone else, from this planet at least.

One last point on this topic: I was made to wonder if there was originally going to be more of a romantic rivalry between Captain Hendry and Dr. Carrington over Nikki Nicholson when I read the following introductory description of the head scientist from the 1950 draft script:

“At a large flat-topped table in the room sits Dr. Arthur Carrington. He is a man of 43 with an alert, cheerful face. He is good looking, well built, soft spoken. His dominant characteristic is a smile that seems never to leave his lips. It is present always on his face like an extra feature. He is a genius of science and a man whose brain is focused like a microscope on the secrets of nature. But the intensity of his preoccupation with science is not to be heard in the easy tones of his voice. It will be seen in the things he does, in his point of view – but never in his manner. Outwardly, he seems only a good looking man full of child-like enthusiasm for a task and with a soothing, amiable way for his fellow man.”

…

“Captain Henry stands silently in the doorway, his eyes moodily on his scientific rival. The doctor is studying the indicator dials of a complex instrument on the table. Bill Stone greets the arrivals.”

The final result for Dr. Carrington created a character who was indeed a rival for Captain Hendry, but in a manner rather different from the usual thematic pattern.

Putting Things in Perspective

Just as the appearance and actions of the alien did with the airmen at the research station, the rapid pace of science and technology after the Second World War frightened the general public, many of whom did not really understand such concepts as nuclear physics, except to focus on the fact that one version of it could annihilate the world in large enough quantities with little warning.

They also often understood the practitioners of science even less, except for what they saw portrayed in their entertainment media. The Thing did its level best to make Dr. Carrington the catch-all example of scientists as a whole through a somewhat distorted and not entirely cloudless cultural lens.

Had The Thing been produced after October of 1957, when the Soviet Union lobbed the first artificial satellite into Earth orbit called Sputnik 1, then Dr. Carrington may have instead been turned into the true hero of the story.

That 184-pound silver ball with four radio whip antennae trailing off its sides shocked Americans into the realization that if the USSR could make an object circle the entire planet over and over with one of their rockets, then they could just as easily deliver a nuclear bomb to any part of the United States in a manner of minutes using the same technology.

American authorities at multiple levels felt it had fallen behind in educating its citizens in the sciences and technology, particularly in regards to space. Almost immediately an overhaul of the nation’s education system began with an emphasis on those subjects to close up what they perceived to be a serious gap with and lag behind the Soviet (and therefore Communist) system.

Thus my prediction that had The Thing been produced after 1957, Dr. Carrington’s high scientific knowledge and enthusiasm would have gone from being a suspicious hindrance and danger to the group to become the very qualities that literally save the day. In the actual 1951 film, he did mention multiple times how science was the only real tool that could “defeat” the alien visitor, at least in terms of understanding and communicating with the being to hopefully avoid the outcome that ultimately unfolded.

As will be discussed in more detail later on, even though Dr. Carrington would fail to sway the alien with his preferred methods, the scientific knowledge he and his colleagues did provide from their examination of the extraterrestrial did give the airmen the knowledge they needed to bring down their adversary after their more traditional weapons fell short due to the alien’s unconventional physiology.

The Thing itself may also have been turned into a more sympathetic character if the film had been released once the Space Age had begun in earnest, rather than a largely inhuman antagonist. One example of this theme was given early on in this essay with the 1953 science fiction film It Came from Outer Space. Another example comes from a 1967 episode of the original Star Trek television series titled “The Devil in the Dark”. The ETI in this case is a being called a Horta, a large silicon-based organism that is essentially a living rock.

In a future interstellar society called the United Federation of Planets (UFP), there exists far below the surface of an alien planet in its territory labeled Janus 6 a being that calls itself a Horta. This decidedly non-humanoid life form looks like a large blob of molten lava and can move through solid rock with ease thanks to a highly corrosive acid it produces from its body.

As we learn early on, this Horta has been attacking and killing dozens of the human residents of a Federation mining colony stationed on Janus 6 without seeming provocation. The being’s physical appearance and behavior has left the miners convinced that it is nothing less or more than a dangerous monster acting on instinct towards the humans which cannot possibly be reasoned with. Therefore, the creature must be exterminated before the mining facility has to be abandoned, losing access to the planet’s great stores of valuable mineral resources for the greater Federation.

Starfleet, the quasi-military organization that conducts both exploration and defense for the UFP, is called upon to stop this threat and save the miners and their operation. At first the officers of the starship assigned to handle this situation, the USS Enterprise, are led to similar thoughts about the native life form when they encounter it deep in the planet’s dim caverns. They too think the Horta is a purely destructive force that needs to be eliminated before they are all killed by it.

However, a series of events convinces the starship officers that this “living rock” is actually a highly intelligent and sensitive being. Eventually direct communications are established with the Horta. They learn that this alien is a mother who was defending her eggs, which are the thousands of silicon nodules found by the miners throughout the vast network of tunnels and chambers far beneath the surface of Janus 6. These spherical objects were being casually destroyed by the humans during their mining operations, as they did not recognize the nodules as the biological product of an ancient and highly intelligent organism – the last of its kind, in fact.

The mother Horta naturally viewed these strange alien bipedal creatures invading her world and killing her unborn children as monsters and acted accordingly.

An understanding is reached between the two species: The young Hortas who later hatched from those surviving nodules would help the human miners find all sorts of mineral deposits and with much greater efficiency, ensuring both the survival of the Horta and the continuation of the UFP colony and its importance to the galactic civilization that spawned it. Both sides also learned to tolerate and accept each other despite their initial mutually visceral reactions to the other’s wildly different physiologies.

This famous episode of the Star Trek series and many other entries from that franchise add further examples to the premise that when it comes to humanity encountering the unknown Other, the situation does not automatically have to turn into an Us-Versus-Them battle for survival with only one winner arising from the conflict. Most often it is when one of the groups make a genuine attempt to understand and communicate with the other that a non-lethal resolution has a chance to happen, while not sacrificing the entertainment demands for action and drama in the process. Writing such stories also gives our species one more roleplay example to practice with and learn from for the day when humanity finally does meet with real beings from other worlds.

Now That We’ve Got Them Just Where They Want Us

“Right, now that we’ve got them just where they want us.” – Captain James T. Kirk, quoted in Star Trek: The Motion Picture (1979)

You have read throughout this essay that The Thing from Another World was biased towards its alien (and potential ETI in general) being hostile and threatening not only to the hapless crew at the remote Arctic research station, but all life on Earth. So how did a small collection of military men and scientists, who before encountering the crashed alien starship and its lone occupant would have considered the idea of beings from other worlds to be science fiction at best, if they contemplated the concept at all, suddenly become experts on the motives of such a life form? In particular, one that the humans had destroyed its vessel through their hurried ignorance of the ship’s composition and was clearly in no mood to convey any information about itself or its actions to such comparatively primitive and violent creatures.

The answer would seem to come from human intuition, which in the case of the film’s characters, the non-scientists had the upper hand on. The airmen, being trained in the ways of military thinking and having participated in combat in World War Two just half a decade earlier were suspicious of the alien from the moment they learned that the “aircraft” the research scientists detected showed unusual flight behavior.

This was the early height of the Cold War. The airmen would have been stationed in Alaska as part of the United States presence to monitor the relatively nearby Soviet Union across the Bering Strait. They would also be there to dissuade their geopolitical rival from deciding to occupy such close American territory (Alaska had been part of the United States since its purchase from Russia in 1867, but it would not become an official state until 1959) or engage in even more elevated military actions on a larger scale.

The Korean War was also underway when The Thing took place: There is no mention of that conflict or that these men were directly involved with it. However, this early major “police action” of the Cold War heightened real world fears that things could expand beyond the Korean peninsula and trigger a nuclear response. Assuming this event was also occurring in the reality of the film, our military characters would be on alert to respond to any type of activity deemed suspicious – at least the terrestrial kind.

As noted earlier, the soldiers assigned to guard the alien while it is still in the block of ice are terrified of its appearance, with its “crazy hands and no hair” – although if the filmmakers had been able to make the alien look more like the description of the Thing in the founding 1938 story, they might have really had something to be terrified of. They can only assume anything which they see as frighteningly ugly is therefore also automatically dangerous with evil intentions.

Image: Dr. Carrington and his fellow scientists of Polar Expedition 6 studying how the Thing reproduces in the greenhouse of the Arctic research station.

Once the alien has responded to being shot by the guards and attacked by the sled dogs and then it is discovered that it uses blood for nourishment and can reproduce asexually via seed pods, it is Dr. Carrington’s secretary, Nikki Nicholson, who voices a theory as to why the alien has come to Earth in the first place.

Nikki has this discussion with her boss, which has been taken from the 1950 draft script as it adds some useful details which were left out in the final film version.

Nikki: “You’re not thinking of what’s happening in the greenhouse. You saw what one of them can do! Well, just imagine if there are a thousand, or a hundred thousand!

Carrington: “I have imagined it.”

Nikki: “And you won’t do anything?”

Carrington: “I’m doing all that can be done, Nikki – discovering its secrets.”

Nikki: “I know! And that’s quite wonderful. But what if that ship came here not just to visit the earth, but to conquer it! To start growing some kind of a horrible army. And turn the human race into – into food for it! And kill the whole world.”

Carrington: “There are many things threatening to kill our world, Nikki. New stars and comets shooting through space. Atmospheric changes. A sudden cooling of the sun. And even human wars – that may release deadly global gases.”

Nikki: “But those are theories, Arthur! This is an enemy – near us – and – ”

Carrington: “There are no enemies in science. There are only phenomena to study. We are studying one.”

Nikki: “You’re not afraid?”

Carrington: “I’d be a traitor to human reason if I allowed my fears to destroy what has come to us – or let anyone else destroy it. I want you to believe in my way, Nikki – the way of the mind.”

In the dialogue where Dr. Carrington is describing other possible threats to humanity, he is more on target than they probably knew in 1950. We now know better than ever how dangerous a rogue comet or planetoid could be to Earth if one impacted our planet (the idea of one wiping out the dinosaurs 65 million years ago did not gain wide scientific acceptance until the early 1980s). Climate change and industrial pollution have certainly played a role in causing major changes to Earth’s atmosphere, not to mention the rest of our planet. If nothing else, it would be difficult for Nikki to casually cast off the idea of human wars creating deadly gasses and other weaponry that could threaten our species as just a theory, in both her time period and ours.

This dialogue also lends credence that while Nikki may be right about the alien at the research station being a real and immediate threat at least to them, in the wider context of the whole debate about the intentions of any actual ETI, natural objects in nearby space and certain real humans on Earth have much higher chances of causing disaster and death for us than beings for whom there is still no solid evidence of their existence, let alone their intentions.

In regards to Nikki’s declaration that the alien has come here to create “some kind of a horrible army” and use terrestrial life as a source of food, her response undoubtedly came from the fact that the alien can and did reproduce rather rapidly by producing seed pods from its body, then feeding the developing young inside them with human and dog blood.

The film bends us to think that Nikki’s speculation is the true intent of the alien. To take a page from Dr. Carrington calling upon real terrestrial examples of plant life that can seem to behave like animals, it could also be that the crash-landed and stranded alien might have been trying to preserve, if not its actual self, then its genetic material.

This scenario reminded me of an event that I personally witnessed when I once went salmon fishing with my family. I discovered that male salmon, when caught and pulled out of the water, do something which rather surprised me: The males shoot out a stream of sperm in what can only be described as a last ditch attempt to carry on its genes, desperate and hopeless as this gesture may otherwise seem (the things they do not tell you in most nature documentaries).

This action is very likely not a conscious response in the fish’s case, but rather an automatic survival reaction similar to the famous fight-or-flee response to danger. Perhaps the alien was doing something similar, even though of course it would have been aware of its purpose in producing seed pods. Highly intelligent and advanced or not, the alien still had basic instincts like all living creatures and acted upon them – with the survival of itself and its species no doubt being on the forefront of its list of important activities to conduct.

You could say this too is just speculation, but then again so is Nikki’s, lacking any direct confirmation or denial from the alien itself. Dr. Carrington was not wrong when he said communication is key to understanding.

Nikki, the lone major woman character in The Thing (there was one woman scientist at the research station, the wife of Dr. Chapman, but her role was small) had yet another collection of expressed thoughts in regards not just to their alien “visitor” but about the idea of ETI coming to Earth in general.

This conversation comes from the released film when the alien is still considered to be a dead specimen frozen in that block of ice:

Nikki: “What does that boogeyman in ice really mean?”

Hendry: “I don’t know, Nikki.”

Nikki: “Well, does it mean that we’ll have visitors from other planets dropping in on us? Do we have to return the call, or… Oh, jeepers.”

Hendry: “I know. Yesterday I’d said it was crazy.”

Nikki: “I’d say it’s crazy now.”

Hendry: “Forget it. Tomorrow it’ll all seem different.”

Nikki’s facial expressions and gestures during this scene make it clear that she is not very enamored of the idea that extraterrestrial beings may now be coming to Earth on a regular basis and that humanity might actually have to talk to and associate with them. The very idea itself is not one she or her companion Hendry ever took seriously until they personally found that alien ship and its living occupant in the ice. It is safe to say that these two and the rest of the non-scientists at the station have little interest in ever joining any type of Galactic Club, should one exist.

The scene itself seems mild, an almost casual conversation about a subject that would have been esoteric if not outright embarrassing for our two characters just the day before. That it is such a simple, short, and straightforward “evaluation” of the idea of ETI contact only makes it that much more palatable to the audience, who are continually conditioned to root for the “alien-is-bad” line of reasoning and its mouthpieces.

It is also interesting to note that it is Nikki who first comes up with the idea of how to dispatch the alien after bullets and even cruder methods have failed. While she and the airmen are speculating on how to stop their unwanted guest, someone asks what does one do with a vegetable. Nikki responds with: “Boil it. Stew it. Bake it. Fry it.”

This idea spark leads the men to attempt to burn it to death by dousing it in kerosene then setting it aflame. When that effort fails (in a scene that quite frankly looks like it had the potential to turn deadly for the cast and production crew in real life), they then try an electrical trap, which does succeed.

Image: The Thing as it is about to walk into what the human protagonists hope will be a successful trap to stop it from turning them all into dinner.

No one outside of Dr. Carrington even ventures the idea of communicating with the alien in any way; they only want the creature killed or otherwise destroyed by some method of brute force. The airmen did make some earlier vague suggestions about confining the alien after it escaped the ice block, which is what their superior officers wanted to be done with it, but even capturing the alien alive goes out the window once the danger of the situation escalates.

Another piece of speculation on the alien and its motives that was in the 1950 script draft but removed completely for the final film were its reasons for landing at the North Pole as opposed to anywhere else on Earth.

The scientists first speculate that the alien came from a world that was generally colder than Earth with a thinner atmosphere based on such things as its seeming lack of ears for hearing sounds (they guess that the being “receives magnetic impressions” rather than hearing and seeing as humans do, even though it definitely has eyes that appear and act like ours) and the way it can survive out in the Arctic snow storm even after it has been presumably injured multiple times and with only a thin type of coverall on its body. Also, in the final makeup form of the Thing, the being definitely has human-shaped ears located on either side of its head.

Then they and Captain Hendry come up with some ideas as to why the alien would choose to land in the frigid and desolate Arctic, presuming it did not arrive there by accident due to some technical issues with its ship:

Voorhees: “It ran out into the cold. I think our surmise that it requires a cold temperature is correct.”

Laurenz: “Obviously. That’s why the saucer tried to land in our Polar regions. They corresponded to the conditions of its own planet.”

Hendry: “There might be another reason. Its passengers could have wanted to keep their arrival secret.”

Note how the scientists are thinking about the alien’s motives based on its physiological needs first, as if it were here only to explore. Captain Hendry is thinking in terms of its strategic motives for conquering the planet. Of course the scientists could argue that the alien would want to remain hidden from humans in order to study us without causing any disruption, just like human scientists study animals in the wild using blinds and other means of camouflage in order to witness and record the true behaviors of their subjects.

On the other hand, the remote Arctic may not be the best place if the alien wanted to find a large quantity and cross-section of humanity. For that matter, the alien (and any cohorts aboard that spaceship) could have stayed in Earth orbit and monitored us remotely if exoanthropology were among its motives.

As The Thing takes place and was made years before the first human-made satellites were sent into space, attempting to watch our activities from hundreds of miles above our planet’s surface or more may not have been taken into serious consideration at the time, being thought of as too remote to learn anything useful.

In addition, the idea of sending unmanned vessels using Artificial Intelligence (AI) to explore space and other worlds, instead of ships with living, organic crews, would have been another fairly novel concept at the time. Yes, by 1951 several nations were using unmanned V-2 rockets captured from Nazi Germany at the end of World War Two to carry cameras and other basic instruments on brief forays to the edge of space. However, the idea of “marrying” a complex computer with a launch vehicle would have been difficult at best: A typical “thinking machine” circa 1950 was very expensive, had weight ranges measured in the tons, and filled up a large room. Miniaturizing computer technologies to fit inside a spacecraft on top of a rocket were another concept that would have to wait for the real Space Age to begin on Earth.

Of course the alien may have detected the electromagnetic signals (radio, television, and radar) being leaked from our civilization as a motive for coming to Earth. His species may also have been able to detect our planet’s multitude of biological life signs, which could be accomplished as far away as their home world using an advanced form of spectroscopy.

While we know the plot scales are tipped in favor of a malevolent reason for the alien being on Earth, the previous examples show it could still have come here for purely scientific exploration, its landing near the North Pole an accident as much as a planned place to study us without disturbing the natives.

Dr. Carrington may have taken the more rational and peaceful approach towards the alien, but that did not mean he was without his own biases. As we have seen multiple times over, the lead scientist insisted that because the alien arrived on Earth via a starship, it was therefore much more knowledgeable about science and technology and therefore it must be automatically wiser – with the implicit addition that the being was therefore also more ethical and moral. In addition, Dr. Carrington was rather swept away by the fact that the alien did not reproduce via “messy” sex. For him this was yet another sign that the alien came from a superior species.

As we have seen on Earth, a technologically advanced human society does not automatically indicate a kinder and gentler populace. As history has shown, it often means that the nation or culture with the better technology is simply more efficient at subduing and even wiping out any opposition. Either that or subjugating less powerful and sophisticated groups for their land, resources, and other items that might increase their position.

Even for species that do not possess any real technology, a higher-functioning brain does not therefore mean they will be necessarily more ethical or even just “nicer”. Dolphins are among the most intelligent creatures on Earth, with brains perhaps comparable to humans. Yet certain types often behave within their own species and others in ways that, were they members of human society, would immediately label them criminals.

This analysis does lead into questions of how one can (or should) judge a non-human species by human standards of behavior, especially when even humanity is often divided on what is considered to be moral and ethical, good and bad. If the alien in The Thing did come here to propagate its species on a new world, how is it different from all the organisms on Earth that have competed with other terrestrial creatures for dominance on this planet since their first microbial ancestors appeared over four billion years ago?

Imagine a situation where Earth was becoming uninhabitable for its native organisms: Would it be considered wrong for humanity to seek out another world in the Milky Way galaxy to continue ourselves and whatever other terrestrial life forms they could bring with them? What if they found a suitable world to colonize that was already occupied by its own flora and fauna, including species deemed intelligent enough to compare to humanity? What if the natives of that planet did not want any new neighbors, yet our species’ survival depended upon settling their world? Who would be in the right: The original occupiers of this planet? The would-be human colonists? Or the species that may end up best dominating that globe?

Suppose the alien in The Thing came to Earth because their world could no longer support them? Would they have any less of a right to inhabit our planet to survive than we would if we needed their world to sustain our species? Even if a species had deliberately wrecked their own world through neglect, greed, or war so that their only other choice was extinction?

Evolution is often thought of by the rule of survival of the fittest. If the species of the alien in The Thing is more suited for surviving in this Universe than humanity – and its ability to withstand extreme environmental conditions and various trauma that would dispatch a typical human in short order was witnessed multiple times – does its kind deserve to overtake the stars?

Humanity has certainly considered itself the predominant life form of Earth for ages, even to the point of proclaiming our species was divinely ordained to rule over the planet and utilize its other organisms and resources as it sees fit, since they were presumably placed there specifically for humanity. It is hardly impossible to imagine that such an egocentric view might not be unique to our species across the stars, as dominating cultures rarely think less of themselves as a whole or tend to shy away from gaining more territory and power when the opportunity arises.

If the plot situation in The Thing from Another World had been reversed, where a team of Terran military personnel found themselves on a starship that crash-landed on the world of the alien from the film: Who would the audience be rooting for as the humans undoubtedly would do their very best -indeed, whatever they had to do, if necessary – to survive on a world where the life forms would very likely react to their presence in a manner quite similar to how they reacted to the alien, especially once it had been revived and free in the Arctic research station?

Furthermore, if these humans went so far as to attempt to secure their survival by becoming the new dominant species on that alien planet, either subjugating the natives or snuffing them out, would not many consider them to be brave and audacious heroes, especially back in the era of The Thing‘s first release. These humans would see the military men as warriors protecting and preserving the galaxy from dangerous aliens for our species.

That was certainly the theme in the 1997 film Starship Troopers, where a future fascist humanity is on a quest to rid the Milky Way of a nonhumanoid alien species they derisively nickname the Bugs. The few public calls to consider the situation from the Bugs’ point of view, including the possibility that we may have invaded their celestial territory first and thus their hostile response, are quickly dismissed and quelled. The leader of the Terran Federation, Sky Marshall Diennes, brings home the government’s position during a broadcast speech: “We must meet this threat with our courage, our valor, indeed with our very lives to ensure that human civilization, not insect, dominates this galaxy NOW AND ALWAYS!”

Here was Manifest Destiny taken to a stellar level. The film brings up the possibility that instead of an ETI civilization being the conquering aggressors bent on dominating the galaxy so often seen in science fiction, it could be humanity which becomes the “alien” invaders to be feared and despised by other societies across the stars.

This leads to another pertinent issue that was also tipped in favor of the human characters: Who and what would be considered either good or evil, or are these largely human judgement values that become increasingly parochial when compared on a literally cosmic scale? We naturally gravitate towards the idea that if something is beneficial to our species it is therefore good, whereas anything harmful is deemed bad or worse.

However, then how does one define something like a virus, which might be deadly to humans, yet we know that they act as they do with neither purposeful ill intent nor even a consciousness. They exist to make copies of themselves, just like virtually all known species do, just on a much more rudimentary – although certainly highly efficient – level.

Now take this perspective to a galactic scale: What if humanity or other similar types of intelligent biological life forms that may attempt to colonize the Milky Way galaxy are perceived by ETI of a very different makeup or are similar to a Kardashev Type 3 civilization, one that spans and utilizes the resources of an entire stellar island like the Milky Way, just as we generally look upon viruses.

We would not tend to see our interstellar expansion as a spreading disease because we have yet to become fully and truly conscious as a culture of the literally much wider picture. After all, humanity and the single planet it currently occupies at present are virtually microscopic in comparison to the rest of the Cosmos. Yet such a lack of cosmic awareness may not spare us from the more advanced ETI’s response to what they may well see as a form of virus infecting their society’s “body”.

Recall the quote at the beginning of this section from the 1979 science fiction film Star Trek: The Motion Picture: That first cinematic installment of the Star Trek franchise dealt with the mostly-human crew of the starship Enterprise encountering a vast alien being calling itself V’Ger. This ETI hailed from (though not originally) a planet occupied by “living machines”, also known as Artilects, or artificial intellects.

As a result, V’Ger perceived the Enterprise as a fellow living being, albeit much smaller and far less sophisticated, whereas the multiple organic creatures it found inside the vessel were labeled as “carbon units” and therefore were “not true lifeforms” so far as V’Ger was concerned. The artificial alien further thought these carbon units were actually infesting the starship like a disease, keeping it from properly functioning and undoubtedly a threat to its overall existence.

Obviously the scenario with V’Ger is a fictional one, but how often have humans dispatched other organisms they do not consider to be their equals – which is just about everything else on this planet – not only with little to no consideration, but also with the thinking that their duty to remove creatures they consider to be harmful or worse to their fellow humans.

For that matter, how often have humans committed acts of genocide against other human beings, often due to little more than minor differences in appearances and customs? There is usually a justification made for such aggressions; even slim ones can be enough to behave in ways that on an individual scale would be considered nothing less than assault and murder.

Image: The human denizens trapped in the Arctic research station prepare for their final confrontation with the Thing.

Now imagine how contemporary humanity might respond to beings that are truly alien to our world in virtually every way, and vice versa. The results may well be what we have seen in The Thing, with fear and aggression winning out over reason, logic, and overtures of peace, or at least neutrality.

At the end of The Thing, with the alien threat safely eliminated, we find the reporter Ned “Scotty” Scott finally able to broadcast his incredible story to the outside world via radio. Here he beseeches his listeners to tell “everybody wherever they are: Watch the skies everywhere. Keep looking. Keep watching the skies!”

While one can appreciate this warning from the reporter in the context of his reality’s encounter with an ETI, one may also imagine the heightened levels of paranoia and fear that will now be growing in that human society over anything foreign appearing in Earth’s skies. Authorities will be flooded with reports of unidentified flying objects beyond the already voluminous amounts of such sightings that already existed at the time: Some sighting stories will be legitimate and useful additions to the UFO database, but many more will be either misidentifications or outright hoaxes. Throw in a Cold War that was also a hot one in certain parts of the globe, and it will likely be only a matter of time before someone shoots down a non-hostile terrestrial aircraft, mistaking it for yet another alien invader.

Then there is the possibility that the next visitors to Earth will be either peaceful or at least neutral explorers, or have other motives for traveling here that may either benefit humanity or cause no real harm, if nothing else. All that may change and become a self-fulfilling prophecy if the military panics and attacks them without provocation. Or civilians could fall victim to a mob mentality and conduct equivalent harm on anyone who is not a terrestrial native, or at least attempt to cause their demise. This attitude could even extend to other humans who show any form of support or even sympathy for those do not come from Earth.

This is why we should not and cannot leave the “discussion” about alien life and its possible motivations to science fiction media, be it from over half a century ago or now. I have often said that the general public gets its “education” about the world and various concepts from the films, television programs, and written works produced by our cultures. They often tend to take these messages to heart, whether they are accurate or not.

Some try to dismiss such media as merely harmless entertainment designed purely for profit – “it’s just a movie,” as they like to say. Yet if one is presented with a work that involves thousands of people and multiple industries to create, costs many millions of dollars to produce, and has numerous deliberate messages implanted throughout for its audiences, then it is most definitely not mere entertainment.

The Thing from Another World falls squarely into this category, despite looking like a more-or-less typical monster horror film of its day. That The Thing does look so “harmless” on its surface makes the fact that it is so biased against rational science over a more warlike stance all the more problematic. How many could honestly walk away from this film and not sympathize and side with the protective and friendly airmen over the emotionally aloof Dr. Carrington and his cold logic, even though most of his scientist colleagues at the research station did not share his fanatical attitude towards the alien, no matter where your preferences usually lie?

This is why the professional science community needs to really ramp up both their science education and outreach with the general public on the subject of alien life and the possibilities for and consequences of contact. While we cannot know how, when, where, or exactly why this event may occur one day, we can at least attempt to prepare ourselves and our species.

Being armed with knowledge and not just weapons may make all the difference, especially since it is just as plausible that our first real experience with an ETI may not resemble what Hollywood and other science fiction works have come up with – which in many cases is a good thing for our species, seeing how often they focus on malevolent aliens.

Should the science community fall short in providing the public and non-scientific authorities with guidance in this arena if a contact scenario goes awry due to the actions or inactions of either parties, scientists may find themselves being thought of and reacted to in the same way the airmen and the film audience did with Dr. Carrington.

The science community also needs to work together and push for improved methods to detect extraterrestrial life in all its possible forms. This means both an increase in SETI and METI efforts and exploring other star systems directly with interstellar vehicles. Breakthrough Starshot has made notable opening efforts in all of these areas, bringing awareness, respectability, and proper funding to fields that were often treated as either mere academic exercises or ridicule by much of the professional community.

Nevertheless, we need to be cautious about any singular organization being representative of the whole arena. Until the late 1990s, most American SETI efforts were dominated largely by radio astronomers with only token responses allowed from other fields, including ones that should have been equally as prominent considering the subject matters involved.

As a result, SETI projects in those otherwise pioneering days were focused on listening for radio transmissions from beings dwelling on Earthlike exoplanets circling yellow dwarf stars. Interstellar travel was largely dismissed as either very difficult or impossible to achieve, discrediting the concept of UFOs as alien vessels in the process. In other words, they were looking for versions of ourselves, even though other authorities and other nations involved in the SETI effort, like the Soviet Union, said that the evolutionary odds of alien beings resembling and behaving like us were slim.

Hollywood went on to reinforce this notion of aliens either appearing or at least acting like humans, often if for no other reason than the early science fiction films and television series could neither afford nor do expensive and elaborate nonhumanoid costumes and makeup.

For the fascinating and often otherwise untold history of SETI and astrobiology, please read this online thesis by Mark A. Sheridan:

http://www.daviddarling.info/encyclopedia/S/SETI_critical_history_contents.html

The Moment of Dr. Carrington

Throughout most of the events in The Thing, Dr. Carrington has been made to come across either as a naive fool at best (he and his fellow scientists were described as acting “like kids drooling over a new fire engine” in their initial reactions to the alien) or tantamount to working with the Thing against the best interest of his own species.

Even near the end, when the airmen had set up a way to electrocute the alien into oblivion, Dr. Carrington attempted to stop them by shutting off the station’s generator powering the trap and threatening them all with a revolver if they tried to turn it on again. The scientist was quickly subdued and hustled into another room for his own safety as much as theirs.

Then the unexpected occurs: Just as the alien is walking towards the airmen, brandishing a long wooden board as a weapon for the final standoff, Dr. Carrington suddenly emerges from behind them, bursting through the group and running straight towards the alien!

The scientist moves right up to the alien and stares into its face. Probably as astonished as the airmen are by this brazen act, the intruder stands still long enough to hear Dr. Carrington plead the following directly to it:

“I’m your friend. I have no weapons. I’m your friend. You’re wiser than I. You must understand what I’m trying to tell you. Don’t go farther. They’ll kill you. They think you’ll harm us. But I want to know you, to help you. Believe that. You’re wiser than anything on Earth. Use that intelligence. Look and know what I’m telling you. I’m not your enemy. I’m a scientist who’s trying – ”

Whether the alien truly understood anything Dr. Carrington was saying to it is debatable. However, it may not have mattered, as the alien decides it has had enough of this babbling member of a race that has done nothing but try to kill it: With one swing of its arm, the alien violently knocks the scientist across the corridor, where Dr. Carrington lands on the floor unconscious.

The Thing continues on its menacing path. As the alien steps into the trap, the airmen now give their own “speech” to the intruder: Thousands of volts of electricity, which burn into the being from three different angles. Screaming and flailing about, the alien slowly shrinks until it is nothing but a pile of smoldering ash. The research station – and humanity – are saved from the menace from outer space. This time.

Image: The Thing meets its shocking end at the hands of the United States Air Force.

After this it is clear that the airmen and the reporter now have a new level of respect for Dr. Carrington that before was only inclined towards his higher education and intellect compared to theirs, along with his prestigious reputation in the scientific community. Right or wrong, the scientist had proven that he was willing to put his own life on the line for what he believed in, doing something none of the others would have dared to attempt unless cornered – and certainly not unarmed!

When Scotty is giving his news report to the listening world via Anchorage, he informs his audience that “Dr. Carrington, leader of the scientific expedition, is recovering from wounds from the battle.” The scientist had received “a broken collarbone and a headache” from his one and only direct meeting with the alien. Captain Hendry gave his tacit approval by quietly responding with “Good for you” to Scotty.

This is a strong contrast to what the filmmakers had originally planned for Dr. Carrington’s final scenes. In the 1950 draft script, the climactic action and dialog largely parallels the released cut, including Dr. Carrington running up to the alien unarmed and attempting to appeal to the being’s presumably superior and therefore better nature.

However, when he pleads “I’m not your enemy – I’m a scientist – a scientist!” the following occurs:

“The Creature has paused before Carrington’s tirade as if studying him. Now, without haste, it lifts one arm, and flicks its hand at Carrington’s throat. Carrington falls to the floor almost decapitated, his last words still gurgling in his throat. The Creature steps over Carrington’s corpse and enters the tunnel. It advances five or six steps.”

In the draft script, the alien is destroyed by the electrical trap, disintegrating in essentially the same manner as it would be shown on screen. The surviving humans’ reactions regarding Dr. Carrington, however, are something rather different:

Nikki: “Dr. Carrington – what happened to him?”

Hendry: (quietly) “He’s dead.”

Skeely (Scotty the reporter): (to Henry. Kneeling over Carrington’s remains) “A clean sweep, Captain. Both monsters are dead.”

In this earlier version, Dr. Carrington is killed outright by the alien, and rather gruesomely at that. Instead of being considered brave and therefore receiving a degree of new understanding, respect, and forgiveness for his previous actions and words, the scientist (and by proxy his profession and field) is lumped in with the alien as just another type of dangerous and non-human creature in need of destruction by the brave, relatable, and very human American airmen.