Farewell to Spitzer after more than 16 years of infrared observations of the universe. We’ve recently looked at the observatory’s accomplishments (see Looking Back at the Spitzer Space Telescope), but I want to run the photo below to celebrate the team that managed it.

Image: Spitzer Project Manager Joseph Hunt stands in Mission Control at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, on Jan. 30, 2020, declaring the spacecraft decommissioned and the Spitzer mission concluded. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech.

Meanwhile, we have the good news that the European Space Agency’s CHEOPS (CHaracterising ExOPlanet Satellite), which was launched from Kourou (French Guiana) on December 18, has completed its early orbit phase, involving instrument tests and calibration, and has now opened its telescope cover, exposing the focal plane to starlight.

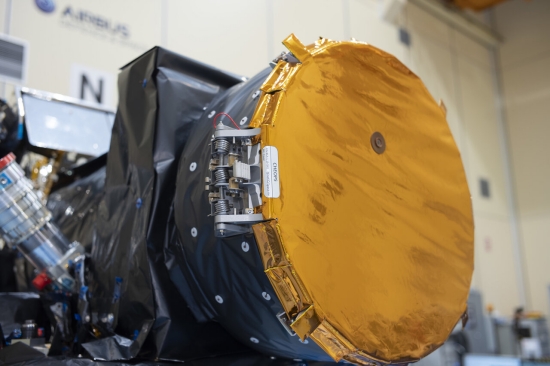

The space observatory carries a 95-cm long baffle that shields its telescope from stray light and minimizes light contamination from sources like the nearby Earth (CHEOPS is in a 700 kilometer heliosynchronous orbit, passing over any given point on Earth’s surface at the same local time). What has been removed is the baffle cover — ESA likens it to the lens cap of a camera — which had protected the instrument from dust and bright light during the initial phases of in-orbit commissioning. The procedure was considered mission-critical, and its successful completion means the telescope cover is now permanently locked in the open position.

Francesco Ratti is a CHEOPS instrument engineer for ESA:

“The opening mechanism is known to be extremely reliable, as it was extensively tested on the ground and already flown on previous space missions, but it was still quite a nerve-wracking moment to witness, and we are all very excited now that the telescope has opened its eye to the Universe.”

Image: The telescope baffle cover of the Cheops satellite, pictured here during spacecraft testings in the cleanroom at Airbus Defence and Space Spain, Madrid, protected the mission’s science instrument from dust and bright light during testing, launch and the early phases of in-orbit commissioning. The cover lid consists of an aluminium frame covered with copper-coloured, multi-layer insulation (MLI) sheeting. The spring-loaded hinge mechanism that connects the cover lid to the baffle is clearly visible in the foreground of the image. On the opposite side of the baffle (not visible in this photo), a locking mechanism held the cover closed. Credit: ESA.

Bear in mind that 80 percent of the observing time on CHEOPS is set aside for a program defined by the science team, but the remaining 20 percent is available to the astronomical community through ESA’s guest observer program, so proposals can be submitted for peer review in a competitive selection process. The observatory will study bright stars already known to host planets, using transit techniques to investigate their physical and chemical properties. For more, see CHEOPS Enters the Game, a Centauri Dreams post from late December.

I wonder whether the CHEOPS team will start a citizen science project, like it was done for Kepler and TESS.

A good question! I certainly hope ESA considers doing this.

Some nice targets for CHEOPS (and a link to the full list) can be found here:

https://www.zooniverse.org/projects/nora-dot-eisner/planet-hunters-tess/talk/2109/1195447?comment=1974480&page=2

I’m not so sure they are that nice. As far as I can see few if any of these stars have known transiting planets . Despite extensive ground observation. Cheops’ primary mission is to refine the transit ephemerides of known transiting planets lying within 40 degrees either side of the ecliptic . So presumably viewing this list would be as part of a highly spectulative fishing trip looking for previously unrecognised transits. Doesn’t sound like a very efficient or productive use of limited and thus highly precious telescope time.

“Cheops’ primary mission is to refine the transit ephemerides of known transiting planets”

No, it isn’t. See for example:

https://sci.esa.int/web/cheops/-/54030-summary

It will (1) use the transit method and (2) observe only stars known to have planets. AFAIK nowhere in the mission plan is stated that the stars must have known *transiting* planets. You mixed (1) into (2) but it isn’t actually in the plan.

Thank you Antonio.

And yes it’s nice to find that surprise finding Teegarden’s Star on the list. Teegardens star is not a flaring dwarf but very still and quiet.

(Contrary to Proxima centauri that burst out in tantrums all the time.)

Ross 128 is also on that list and again with an Earth size planet with a quiet red dwarf primary.

CHEOPS could have some very “CUTE” competition very soon. Check out David Charbonneau’s latest tweet for details.