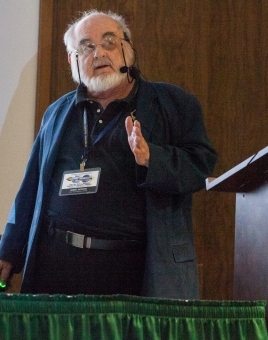

The interstellar ramjet conceived by Robert Bussard may have launched more physics careers than any other propulsion concept. Numerous scientists over the years have told me how captivated they were with Poul Anderson’s treatment of the idea in his novel Tau Zero. Al Jackson takes a look at Bussard’s concept in today’s essay, referencing its subsequent treatment in the literature and adding a few anecdotes about Bussard himself. The original paper was submitted on February 1, 1960 to Astronautica Acta, then edited by Theodore von Kármán (a ‘tough judge,’ Al notes) and published later that spring. Although the ramjet faces numerous engineering issues, its ability to resolve the mass-ratio problem in interstellar flight makes it certain to receive continued scrutiny.

by A. A. Jackson

Writers of science fiction prose noticed the difference between interplanetary flight and interstellar flight earlier than anyone. Various fictional methods of faster-than-light (FTL) were invented in the 1930s, John Campbell even inventing the term ‘warp drive’. Asimov’s Galactic Empire is only facilitated by FTL ‘jump-drives’. Slower than light interstellar travel made an appearance in Goddard and Tsiolkovsky’s writings in the form of ‘generation ships’, usually called ‘worldships’ now.

As far as I know, the first engineer to look at the very basic physics — quantitative calculations — of relativistic interstellar flight was Robert Esnault-Pelterie; he made relativistic calculations before 1920 that were published in his book L’Astronautique (1930). The first derivation of the relativistic rocket equation occurs in Esnault-Pelterie’s writings. This was long before Ackeret (J. Ackeret, “Zur Theorie der Raketen,” Helvetica Physica Acta 19, p.103, 1946). The classical mass ratio rocket equation of Tsiolkovsky showed the difficulty of space travel. The relativistic rocket equation showed that interstellar flight was even more difficult.

Eugen Sänger, who had been interested in interstellar flight in the 1930s, addressed the interstellar mass ratio problem in 1953 with a paper on photon rockets, “Zur Theorie der Photonenraketen” (Vortrag auf dem 4. Internationalen Astronautischen Kongreß in Zürich 1953). Sänger, more than almost anyone before him, studied the hard physics of antimatter rockets and relativistic rocket mechanics. Using the most energetic energy source, antimatter, would require tons of it in a conventional rocket. There was sore need of a better method.

Bussard

Robert W Bussard was a rangy man who looked like he walked the halls of power. I had dinner with him at a San Francisco section of the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics meeting in 1979. We had invited Poul Anderson, author of Tau Zero; Anderson and Bussard had never met. Over dinner Bussard told me he started working on nuclear propulsion at Los Alamos in 1955, and that he and R. DeLauer wrote the first monograph on atomic powered rockets in 1959 [1]. He also said he had been looking at work at Lawrence Radiation Laboratory in 1959.

Bussard told me he had always been interested in interstellar flight. One day at breakfast at Los Alamos he got a tortilla rolled up with scrambled egg in it. That cylinder made him think of a fusion ram starship! I have to wonder if that story is true, for had he been looking at Livermore’s lab papers he probably saw Project Pluto, the nuclear powered atmospheric ramjet.

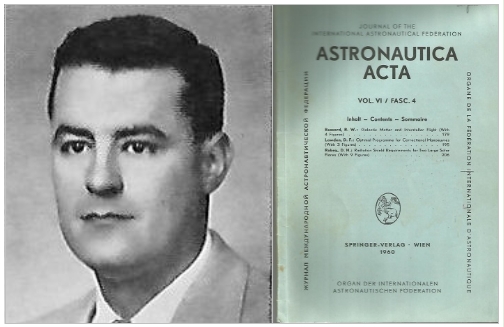

Bussard sat down in 1959 and wrote the paper “Galactic matter and interstellar flight,” published in Astronautica Acta in 1960. This paper is thoroughly technical; Bussard summarizes Ackeret, Sänger and Les Shepherd’s studies of interstellar flight [2]. Sänger had shown that even using antimatter one still had a mass ratio problem with a conventional rocket. Bussard then presents an amazing new concept that solved the mass ratio problem [3]. He notes that one can scoop interstellar hydrogen and fuse it to produce a propulsion system.

The treatment is rigorously special relativistic; using conservation of energy and momentum he derives the equations of motion of an interstellar ramjet. He accounts for the energy production and propulsion efficiency of the vehicle in general terms. He uses the most energetic fusion mechanism, the proton-proton fusion reaction which converts .0071 of the rest mass of collected protons to energy. Bussard derives the property that the ramjet will need to be boosted to an initial speed.

Image: Robert Bussard in 1959 with his Astronutica Acta issue.

Bussard discusses the engineering physics problems; the difficulty of using the p-p chain is enormous. He notes that interstellar hydrogen can be unevenly distributed, there being rich and rarefied regions. He gives a simplified model for scooping and sometimes it is missed that he mentions magnetic fields as a ‘collector’. Bussard also notes both radiation losses and radiation hazards during the operation of the ramjet.

Sagan

The Bussard Ramjet got a boost in 1963 when Carl Sagan noted that there was a solution to the mass ratio problem for interstellar flight [4]. Sagan summarized this paper in Intelligent Life in the Universe in 1966 [5], probably the best popularization of the Ramjet. Sagan also noted that ships accelerating at one gravity could circumnavigate the universe, ship proper time, in about 50 years. He references Sänger in the paper version [4] and the calculation of the mechanics of a 1g starship. As far as I know, the 1957 paper of Sänger [6] is the first exposition of a constant acceleration starship and the consequences of time dilation when extreme interstellar distances are traveled. Bussard mentioned, very briefly, a magnetic field as a scoop, but Sagan describes such a collector in a more elaborated though qualitative way.

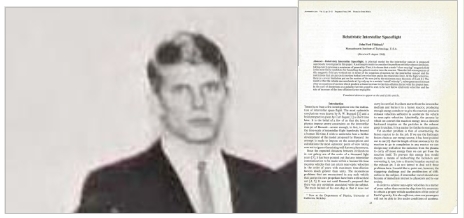

Fishback

John Ford Fishback published his MIT bachelor’s thesis in Astronautica Acta in 1969 [7]; this was supervised by Philip Morrison. Morrison and Cocconi were the fathers of radio SETI. Morrison seems to have taken an interest in Sagan’s mention of Bussard’s ramjet — I’m not sure if it was Morrison or Fishback who suggested the study. The paper is a remarkable marshalling of electrodynamics, charged particle motion, plasma physics, the physics of materials and special relativity.

Fishback constructs a model for the magnetic scoop field taking into account the fraction of hydrogen ingested and reflected. Using conservation laws, he derives the most detailed equations of motion accounting for mass and radiation losses that had been published anywhere. In the scooping process, Fishback examines the statistical distribution of gas in the galaxy and derives a relativistic expression for ship proper acceleration with ‘drag’. An important consequence, expressed for the first time, is the mechanical stress on the scoop field magnets. He derived an upper limit on the maximum Lorentz factor that can be obtained as a ramjet accelerates at 1 g for a long time due to stress on the source of the scoop field.

[For more on Fishback, see Al’s John Ford Fishback and the Leonora Christine from 2016, with further thoughts by Greg Benford.]

Image: John Ford Fishback in 1967 and first page of his paper in Astronautica Acta. Sadly, Fishback would take his own life in 1970 at the age of 23.

Martin

In 1971 [8] and 1973 [9] Tony Martin reviewed Fishback’s paper, making useful clarifying observations. Martin provides details of calculation that Fishback leaves to the reader on the relation of the fraction of particles that are magnetically confined to the reactor intake as a function of the confining field and the starship’s speed. In his second paper, Martin corrects a numerical error by Fishback showing that the cutoff speed due to the stress properties of the magnetic source is 10 times larger than was calculated. Martin also gives a nice calculation of the size of the magnetic scoop field. Fishback and Martin’s papers account for the ‘drag’ due to reflected particles; this result seems unknown to later critics of the ramjet.

Whitmire

I met Dan Whitmire in 1973, when we were both working on doctorates in physics at the University of Texas at Austin. Dan and I were talking about interstellar flight one day and I showed him Bussard’s paper. Dan was in the nuclear physics group at Texas and took an immediate interest in the problem with proton-proton fusion as had been pointed out by Bussard and Martin. Then he came up with an ingenious solution: Carry carbon on board the starship and use it as a catalyst to implement the CNO fusion cycle [10]. The CNO process is 1018 times faster than the PP chain at the fusion reactor temperatures under consideration. This reduces the fusion reactor size to 10s (and more) of meters in dimension. Since carbon cycles in the process, in theory one would only need to carry a small amount; however it is not clear how under dynamic conditions one would recover all the catalysis needed.

Later Developments

The above are the core studies of the interstellar ramjet. Hybrid methods occurred to several researchers. Alan Bond [11] proposed a vehicle that carried a separate energy source yet scooped-up interstellar hydrogen not as fuel but simply as reaction mass, this is known as the augmented interstellar ramjet. Conley Powell [12] presented a refined analysis of this system. The author [13] presented a study using antimatter added to the scooped reaction mass for propulsion as an augmented method. Relevant to the augmented ramjet is antimatter combined with matter for propulsion as studied by Forward and Kammash [14, 15].

T. A. Heppenheimer published a paper in the Journal of the British Interplanetary Society [16] noting the problems with the p-p chain for fusion without citing Dan Whitmire’s solution. Heppenheimer notes radiation losses but does not cite Whitmire and Fishback, who addressed the problems of bremsstrahlung and synchrotron radiation in the reactor and the scoop field.

Matloff and Fennelly [17] have interesting papers on charged particle scooping with superconducting coils. Cassenti looked at several modifications and aspects of the ramjet [18].

Recently Semay and Silvestre-Brac [21, 22] re-derived the equations of motion of the interstellar ramjet, first done by Bussard and Fishback. They find some new extensions with solutions of the relativistic equations for distance and time.

Dan Whitmire and the author [23] removed the fusion reactor by taking the energy source out of the ship and placing it in the Solar System. If one scoops hydrogen but energizes it with a laser system it is possible to make a ramjet that is smaller and less massive. Such a system probably has a limited range similar to laser pushed sails.

An excellent survey of interstellar ramjets and hybrid ram systems can be found in the books by Mallove and Matloff [24] and a recent monograph by Matloff [25], see these books and the references listed in them. See also Ian Crawford’s paper [26].

The Interstellar Ramjet in Science Fiction

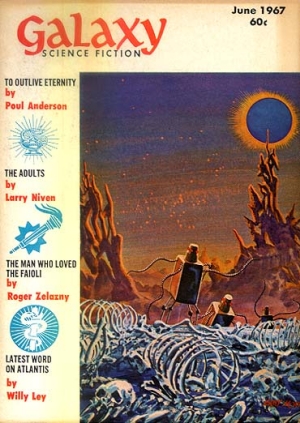

It seems the Bussard Ramjet first appeared in a Larry Niven short story called “The Warriors” (1966). Later Niven used the Ramjet in his other fiction, inventing, I think, the term Ram Scoop. However I think the best known use of the Ramjet is Poul Anderson’s Tau Zero [26]. The core story in Tau Zero is not the Interstellar Ramjet but the constant acceleration circumnavigate-the-universe calculation first done by Eugen Sänger.

My guess is that Anderson only saw Carl Sagan’s exposition on this in Intelligent Life in the Universe. The Greek letter ‘Tau’ was introduced by Hermann Minkowski in 1908; it is the time measured by the travelers in the starship Leonora Christine, while the time measured by people back on earth is t. Special relativistic time dilation leads to (ship time)/(Earth Time) going to almost zero. Accelerate at one g for 50 years and one covers a distance of about 93 billion light years that is roughly the size of the universe.

Image: What would become Tau Zero first appeared in shortened form as “To Outlive Eternity” in the pages of Galaxy in June, 1967.

The Bussard Ramjet Leonora Christine sets out for Beta Virginis, approximately 36 light years away. A mid-trip mishap robs the ship of its ability to slow down. Repairs are impossible unless they shut down the ramjet, but if the crew did that, they would instantly be exposed to lethal radiation. There’s no choice but to keep accelerating and hope that the ship will eventually encounter a region in the intergalactic depths with a sufficiently hard vacuum so that the ramjet could be safely shut down. They do find such a region and repair the ship.

Anderson then introduces the mother of all twists. The Leonora Christine has accelerated for so long that the crew discover relative to the universe a cosmological amount of time has elapsed. The universe is not ‘open’ but fits the re-collapse model, it is going for the big crunch. I know of no other science fiction novel with more extreme problem solving that this hard SF story.

Anderson’s cosmology for Tau Zero seems to come totally from George Gamow [28]. Gamow and his students did pioneering work on early time cosmology, an elaboration of earlier work done by Georges Lemaître. When Poul Anderson wrote the novel, he may have been aware that Big Bang cosmology had evolved beyond Gamow’s models …. However, having his starship eventually orbit the ‘Cosmic Egg’ or Ylem was a solution to the crew’s problem. Alas, even in Gamow’s cosmology the ‘Ylem’ is the universe, so no way to ‘orbit’ it. Poetic license for the sake of a Ripping Yarn! (An intersecting exercise is to see what the trajectory of the Leonora Christine‘s plot problem is in current accelerating universe cosmology.)

After Niven and Anderson, the Bussard Ramjet became common currency in science fiction, although it has faded somewhat in recent times. Recently a fusion ramjet, SunSeeker, appears as an integral part of the Bowl of Heaven series by Greg Benford and Larry Niven [29].

Final Thoughts

There seems to be a thread of pessimism about the Bussard Ramjet centered around drag on the ramjet due to interaction with the scoop field. This is an issue that Fishback deals with in his analysis; he shows one cannot just use a dipole magnetic field. A more complex collector field is needed. Fishback and Martin do show there is a fundamental physics limitation. Even using the strongest material theoretically possible, there is an upper limit to a mission Lorentz factor, probably equal to 10,000. Above this one will bust the scoop coil due to magnetic stress. The cosmological peril of the Leonora Christine depicted in Tau Zero is not physically possible.

The main show stopper for the ramjet is the engineering. There is no way with foreseeable technology to build all the components of an interstellar ram scoop starship. Several aspects should be revisited. (1) The source of the magnetic scoop field, Fishback [7] derived one, Cassenti elaborated another [20]; (2) the fusion reactor — the aneutronic fusion concept is direct conversion of fusion to energy [30]; (3) hybrid systems, especially laser-boosted ramjets.

Since basic physics does not rule a ramjet out, it is possible that an advanced civilization might build one. Freeman Dyson [31] pointed out many times that what we could not do might be done by some advanced civilization as long as the fundamental physics allows it. An interesting consequence of this is that interstellar ramjets may have been built and might have observable properties. Doppler-boosted waste heat from such ships might be observable. Plowing into HII regions in the galaxy, a starship’s magnetic scoop field might produce a bow-shock which could be observable. Isolated objects in this galaxy with Lorentz factors in the thousands would be unusual and if they are accelerating even more unusual.

The idea of picking up your fuel along the way in your journey across interstellar space may be the optimal solution to the mass ratio problem in interstellar flight. The interstellar ramjet warrants more technical study.

Appendix

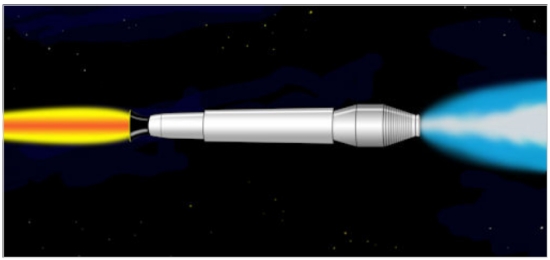

Because Robert Bussard sketched a ramjet with a physical ‘funnel’ …all the many illustrations I have seen since seem to have some kind of ‘cow catcher’ on the front. Though it is reasonable that such a structure is the source of an electromagnetic device, I think it more likely that the ‘scoop’ field will be produced by a magnetic configuration that directs the incoming stream into the mouth of the reactor without any extra funnel-like forward structure. Here is a rough schematic done for me by artist Doug Potter. There is a ‘bulb’ representing the magnetic source field (maybe the parabolic magnetic field calculated by Fishback), a reactor section and an exhaust. Not a very elegant representation of the ramjet but a suggested configuration.

References

1. Bussard, R. W., and R. D. DeLauer. Nuclear Rocket Propulsion, McGraw-Hill, New York, 1958

2. L. R. Shepherd, “Interstellar Flight,” Journal of the British Interplanetary Society, 11, 4, July 1952

3. R.W. Bussard, “Galactic matter and interstellar flight,” Astronautica Acta 6 (1960) 179-195

4. C. Sagan, “Direct contact among galactic civilizations by relativistic interstellar spaceflight,” Planet. Space Sci. 11 (1963) 485-498

5. Sagan, Carl; Shklovskii, I. S. (1966). Intelligent Life in the Universe. Random House

6. Sänger, E., “Zur Flugmechanik der Photonenraketen.” Astronautica Acta 3 (1957), S. 89-99

7. Fishback J F, “Relativistic interstellar spaceflight,” Astronautica Acta 15 25-35, 1969

8. Anthony R. Martin; “Structural limitations on interstellar spaceflight,” Astronautica Acta, 16, 353-357 , 1971

9. Anthony R. Martin; “Magnetic intake limitations on interstellar ramjets,” Astronautica Acta 18, 1-10 , 1973

10. Whitmire, Daniel P., “Relativistic Spaceflight and the Catalytic Nuclear Ramjet” Acta Astronautica 2 (5-6): 497-509, 1975

11. Bond, Alan, “An Analysis of the Potential Performance of the Ram Augmented Interstellar Rocket,” Journal of the British Interplanetary Society, Vol. 27, p.674,1974

12. Powell, Conley, “Flight Dynamics of the Ram-Augmented Interstellar Rocket,” Journal of the British Interplanetary Society, Vol. 28, p.553, 1975

13. Jackson, A. A., “Some Considerations on the Antimatter and Fusion Ram Augmented Interstellar Rocket,” Journal of the British Interplanetary Society, v33, 117, 1980.

14. R.L. Forward, “Antimatter Propulsion”, Journal of the British Interplanetary Society, 35, pp. 391-395, 1982

15. Kammash, T., and Galbraith, D. L., “Antimatter-Driven-Fusion Propulsion for Solar System Exploration,” Journal of Propulsion and Power, Vol. 8, No. 3, 1992, pp. 644 – 649

16. Heppenheimer, T.A. (1978). “On the Infeasibility of Interstellar Ramjets”. Journal of the British Interplanetary Society 31: 222

17. Matloff, G.L., and A.J. Fennelly, “A Superconducting Ion Scoop and Its Application to Interstellar Flight”, Journal of the British Interplanetary Society, Vol. 27, pp. 663-673, 1974

18. Matloff, G.L., and A.J. Fennelly, “Interstellar Applications and Limitations of Several Electrostatic/Electromagnetic Ion Collection Techniques”, Journal of the British Interplanetary Society, Vol. 30, pp. 213-222, 1980

19. Matloff, G.L., and A.J. Fennelly , B. N , “Design Considerations for the Interstellar Ramjet,” 44th AIAA/ASME/SAE/ASEE Joint Propulsion Conference & Exhibit, 2008

20. Cassenti, B. N , “The Interstellar Ramjet,” 40th AIAA/ASME/SAE/ASEE Joint Propulsion Conference and Exhibit, 2004

21. Claude Semay and Bernard Silvestre-Brac, “The equation of motion of an interstellar Bussard ramjet,” European Journal of Physics 26(1):75, 2004

22. Claude Semay and Bernard Silvestre-Brac, “Equation of motion of an interstellar Bussard ramjet with radiation loss,” Acta Astronautica 61(10):817-822, 2007

23. Whitmire, D. and Jackson, A, “Laser Powered Interstellar Ramjet,” Journal of the British Interplanetary Society Vol. 30pp. 223-226, 1977

24. Mallove, E. F., and G.L. Matloff, The Starflight Handbook, Wiley, New York, 1989

25. Matloff, G., Deep-Space Probes, Praxis Publishing, Chichester, UK, 2000

26. Ian A Crawford, “Direct Exoplanet Investigation Using Interstellar Space Probes.” In Handbook of Exoplanets Springer 2017

27. Anderson, Poul. Tau Zero. New York: Lancer Books (1970)

28. George Gamow, The Creation of the Universe (1952)

29. Benford, G. and Niven, L., Bowl of Heaven series, Macmillan.

30. Benford, G., Private communication.

31. Dyson, F. J., “The search for extraterrestrial technology,” in Marshak, R.E. (ed), Perspectives in Modern Physics, Interscience Publishers, New York, pp. 641-655

“The cosmological peril of the Leonora Christine depicted in Tau Zero is not physically possible.”

This was actually dealt with in Anderson’s story, by a bit of handwaving that the primary collection field wasn’t generated by the ship’s hardware, but instead by the plasma itself, and the ship’s hardware was only guiding the growth of that field. So that the faster the ship traveled, the stronger the field got, without hardware limits.

The description of the technology given by Anderson in Tau Zero avoids technobabble as all good science fiction writers do. He does finesse the physics of the instrumentality , somewhat poetically at times. The most direct description is given at the start of chapter 3. Explicityly he is describing the reactor and the scoop field as being electromagnetic at it’s base. So there is hardware very implicitly implied. I doubt he even knew about Fishback’s paper when he wrote the novel. .. Scanning the technicalities in the novel , Anderson has an odd thing which he need not have included, he has the ship doing 3g acceleration while the crew only feels 1g in the ship. His description of the ‘compensator’ is totally incomprehensible , I have no idea why he did this, a constant 1g will get you to .9 % the speed of light in 3 years for sure. No need to push that parameter.

The higher acceleration didn’t just speed up the ship, it sped up the plot. At only 1 G acceleration the events of the novel would have taken a couple centuries ship’s time, minimum.

Lets see, the destination was Beta Virginis at 35.65 light years. Making the calculation at 1g *, accounting for special relativity, that is 7 years ship time , 38 years back home ( tho all we really care about is proper time ship board). Of course to decelerate that’s probably approximately 14 years, could be a lot less if could decelerate quicker (Anderson is a bit vague about the deceleration mechanism). With breakdown, forced to accelerate at 1g it take about 50 years ship time to go 93 billion light years which is a characteristic size of the universe. Those are quite reasonable times to use in a story with interstellar flight. Seems this is set 200 to 300 years in the future, I don’t know if Anderson brings it up, but should be advances in the life sciences that extends lifetimes way beyond 100 years with a youthful body and mind. Anderson did not have to use 3g.

*Edwin F. Taylor & John Archibald Wheeler ,Spacetime Physics , (W.H. Freeman, San Francisco)

But the timeline in the story IS designed to be reasonable for people without life-extension. It was a colonization mission originally, intended to get there quick enough that the crew would still have a good number of fertile years by the time they arrived.

Poul Anderson did use life extension in at least one story, but only as a key plot element. It was not a general background element of his stories.

Looking over the novel I can’t really tell what time scale Anderson framed the narrative around. There is a definite indication that he had read Sagan , and maybe Saenger’s paper that one could circumnavigate the universe at 1g in 50 years ship time , which could put it at the ‘coordinate’ time of re-collapse in a cyclic cosmology. This was the most startling plot pivot point of the novel, or any SF novel I have ever seen.

An interstellar ramjet might break the light-speed barrier if it could be accelerated inside a gridded Casimir cavity. The spacecraft would need to achieve a Lorentz factor of close to a sub-canonical ensemble value. I use the phrase sub-canonical ensemble to denote a very large number of roughly 10 EXP 50 to 10 EXP 1,000.

The idea here would be to alter the inverse square-root of the magnetic permeability and electric permittivity of the free space within the Casimir tube by screening zero point field fluctuations of wave-lengths on the order of the grid-spacing or greater.

A gridded Casimir tube is preferable due to the mass requirement of a tube that would likely need to self-assemble itself over more than one cosmic light-cone diameter. The tube may need to be superconducting but perhaps not too much so if the capture area of the craft would have largest cross-sectional dimensions of say 30 kilometers corresponding to 10 kilohertz electromagnetic radiation.

An extremely conventional conducting tube may be preferable.

Very interesting idea! Do you have more information on this? Maybe websites or articles or books?

Oh, just googled you! Very good reads, what sites can I download your books from?

Although you can down-load my books at Xlibris Publishing, Amazon.com, Barnes and Noble, and Outskirts Press by searching my name in the associated catalogues, I would be happy to send you copies free of charge. Most of these books are really lengthy so I will need to send them to you by Drop Box or We Transfer. My email address is jamesmessig@aol,com I do not mind sharing my email address because if my work becomes more noticed, folks will need to be able to contact me anyhow. Thanks so much for showing interest Michael Fidler!

A nudge here to get back on topic — the Bussard ramjet is the subject of the post.

I will refrain from any more responses to the comments I have received. I respect Paul’s boundaries and this thread is indeed about the Bussard Ramjet, thus my decision not to respond to anymore comments. For those who wish to contact me, I am happy to continue the discussion but this is not the place to do so.

You realize that, even if this works, all it gets you is from 0.999999999 of light speed, to 1.0000000001 of light speed? Only with more 9’s and 0’s?

The Casmir effect is highly dependent on spacing, and only becomes significant as the spacing approaches actual contact. At any spacing you could fit a ship through, it’s so small as to be undetectable.

IOW, it’s perfectly useless, even if it works as theorized.

Faster than light travel velocities would enable backward time travel. In essence, one would arrive at a destination before they left.

A sub-canonical ensemble Lorentz factor in such a tube would more than make up for the reduced Casimir effect thus enabling faster than light travel with respect to the outside of the tube.

“An interstellar ramjet might break the light-speed barrier if it could be accelerated inside a gridded Casimir cavity.”

Why SHOULD a gridded Casimir cavity (whatever a gridded Casimir cavity is) even PERMIT a vehicle to exceed the light-speed barrier – I don’t see it. Can you explain the why it should work ??

A gridded Casimir cavity should work about as well as a monolithic Casimir cavity for screening out photons of wave-lengths longer than the diameter of the cavity and longer than the width of the grid openings. A Casimir cavity works because only wave-lengths for which nodes of the reflected photons exert pressure on the inner wall of the cavity as standing waves. On the outside of a monolithic cavity, zero point photons are not screened. The net imbalance in the forces causes the plates to be pushed together in laboratory experiments.

The idea here would be to alter the inverse square-root of the magnetic permeability and electric permittivity of the free space within the Casimir tube by screening zero point field fluctuations of wave-lengths on the order of the grid-spacing or greater.

The inverse square-root of the magnetic permeability and electric permittivity of the free space is equal to the velocity of light. Note that this velocity for a background for which there is no screening of zero point photon energy much as you would find in interstellar space.

A grid that is conducting or superconducting reflects radio-frequency radiation fairly easily for radiation half an order of magnitude or greater in wavelength than the width of the grid openings. Rf concentrators that are grid like are used all of the time in communication and in radio astronomy to reflect signals.

There are two things–one of which may matter, the other of which definitely matters (makes a difference, that is)–where interstellar travel vis-à-vis Special Relativity is concerned (and it could especially matter to the Bussard ramjet, due to Special Relativity effects):

As Arthur C. Clarke pointed out in his non-fiction book “The Promise of Space,” Einstein does *not* say that no material object can travel faster than light (plugging in figures for > c velocities in the relativity equations gives real-number solutions)–only that no material object can travel *at* the speed of light. Clarke then went on to say that modern physics is full of quantum jumps from one state of energy or velocity to another, ^without^ passing through the intermediate values (he gave as a common example the tunnel diode, in which electrons “tunnel” from one side of a dielectric barrier to the other, without passing through it). Maybe, he continued, we can do the same sort of thing at the light barrier, and:

The speed of light in a vacuum cannot–at least by any means that we know of at this time–be exceeded by simply accelerating through it. But in other media, such as water, particles routinely exceed the speed of light (the speed of light *in water*); Cerenkov luminescence around the parts of a “swimming pool” nuclear reactor results from this. Like intelligent pelagic fish–if they were able to reason–who could not conceive of being surrounded by air, or by a vacuum (and who would seldom even think of being surrounded by water), we have a hard time, being immersed in the space-time we know, to conceive of other possibilities, which might permit faster-than-light travel. Also:

It would be very strange–especially given that a unified field theory still eludes us (we currently have “The Standard Model of Physics, plus Gravity”)–if Einstein’s Special and General Theories of Relativity were the last word on the subject. Even General Relativity has a chink in its armor (or a missing link in its chain mail), as Clarke also pointed out:

GR says that acceleration forces due to gravity and physical acceleration (inertia, as in a spaceship under constant thrust and uniform acceleration) are indistinguishable. This is simply not true. If you measure the force of gravity above, on, and below the Earth’s surface, it will get stronger as you move closer to the Earth’s center, and weaker as you move farther away from it. But if you used the same instrument–a spring balance, say–to measure the “gravity” aboard a spacecraft accelerating at 9.8 meters per second per second, no matter where inside or on the outside of the ship you took measurements, they would always be 1 g, so the two forces are not indistinguishable, which means:

Given our incomplete knowledge, it is simply far premature for anyone to say that “We can definitely do X, given the technology,” or “We will *never* be able to do Y, no matter what level of technology we achieve, because it’s fundamentally impossible.” We are simply not yet in a position to say what is or isn’t impossible (including the Bussard ramjet, and even Alcubierre’s warp drive) with regard to interstellar travel. What a tragedy it would be, if all thought about certain types of propulsion was abandoned simply because of a belief that it is impossible. As the history of science & technology have amply shown, what is “impossible” for one generation often becomes almost ridiculously easy for subsequent ones, thanks to continuous, gradual work sprinkled with occasional, sudden (and often serendipitous) breakthroughs. Don’t count the Leonora Christine out…

Bravo Al. A wonderful in-depth treatment that truly enhanced my burnt baked beans on toast snack!

Something was definitely in the air when that issue of Galaxy was put together: Niven’s “The Adults” was the first section of the novel Protector, where a Pak scout arrives in our solar system on a ramjet spacecraft.

I may be wrong here but isn’t the Universe thought to be expanding faster than the speed of light? Hence the term visible Universe which denotes that portion of the Universe we will be able to observe at any time. So even at the speed of light nobody will ever traverse the Universe will they? A wonderful article Dr. Jackson. Thank you.

Could curvature distort our view of visible Universe, such as if the local Universe is in a depression, sinking? More complexity from observation or matter slowing expansion for a local area. Our positions as relative observers: in a volume perhaps so large as to have infinite surface area yet finite capacity. Position on the volume interior affects measurement of expansion velocity.

The best explanation I know of compares the speed of light in an expanding universe to walking on a moving sidewalk. So even though the universe is only 13.8 billion years old, the size of the universe can be much bigger when measured in light years.

I had not noticed , Poul Anderson defines tau incorrectly in the book.

If beta is the ratio of ship speed to the speed of light.. Anderson defines tau as the square root of one – beta squared. That Lorentz ‘factor’ (that is really the inverse Lorentz factor) is not tau , tau is the product of that factor time the ‘coordinate time’ in this case the clock ticking back on earth. It never literally goes to zero since v is always less than c. However most people are never going to notice that. More poetic license.

Well, yes, Tau Zero was poetic license. “Tau 1×10^-20” wouldn’t have made a good book title.

Having just read the novel–for the first time–two days ago, and having it very fresh in mind, I am quite certain that the title contains an implied word: (“*Approaching* Tau Zero”). On several occasions, each time they think they’ve finally got a solution in sight (which turns out not to be the case), either several of the characters or Poul Anderson–as the narrator–point out that pushing their Tau to smaller and smaller values (by accelerating ever closer to c) will enable them to reach more distant possible abodes in shorter ship times. Also:

Someone has ^GOT^ to make a movie of “Tau Zero.” (Maybe Morgan Freeman? He’s quite interested in producing a “Rendezvous with Rama” movie.) The scene in which the work gang performs an inter-galactic EVA at nearly c to fix the Bussard module, in the absolute darkness–with no detectable cosmic radio static on their suit radios–giga-light-years between galactic clans, is chilling, even though it goes smoothly. Altering the script to reflect the true state of the Cosmos (the super-massive black hole at the Milky Way’s core, the ever-accelerating and diffusing-apart [from each other] galaxies) could make a “Tau Zero” film even more exciting.

Lovely article! Nice to get some personal anecdotes about the pioneers recorded while we can. Bussard and later workers really did outstanding work, even if the particular technological solutions don’t pan out, they got people thinking about the problem in real terms. The whole field of magnetic sails is an offshoot of this work, for example.

Interesting; I had thought that all the people who had really tried to analyze it had all dismissed it as clever but unworkable; I hadn’t realized that there were still some people left who think that it might work.

The Bussard fusion ramjet is a clever idea, but needs about a dozen miracles to work. I have a hard time trying talk myself into believing more than one miracle.

The first problem is hidden right in the middle of Bussard’s paper; at the time Bussard wrote, a best guess for the density of the interstellar hydrogen was “1-2 atoms/cm^3”. Most of his calculations are scaled to scoop mass divided by hydrogen density, and it is only in the example calculation at the conclusion of the article that he gives his assumption: for the calculation he assumes 10^3 protons/cm^3: that is, the example acceleration is for a ship flying through an interstellar hydrogen cloud. The real numbers, unfortunately, turn out to be worse, and not better, than Bussard assumed. The sun is at the edge of the “local cloud”, with a density of 0.1-0.2 partially-ionized hydrogen/cm^3. Our nearest target, however, alpha Centauri, is located outside the local cloud, in the local bubble, about 300 light years in diameter, with density ~0.001-0.05 hydrogen ions per cm^3. So, depending on the direction we go, the density (and hence the acceleration) is either an order of magnitude worse (and effectively worse than that, since most scoop designs only scoop the ionized fraction), or two to three orders of magnitude worse (but with the advantage of being mostly ionized)… and an astonishing four to six orders of magnitude worse than the numbers assumed in his example calculation.

But fuel turns out to be the LEAST important of the problems of the multiple problems. The technical problems can be cataloged basically in three categories: the scoop, the fusion reaction, and turning the fusion product into thrust, each of which categories includes multiple different problems, and each of which does not, as yet, have a credible path toward solution. Note that since fusion energy releases 0.8% of the mass energy of the incident protons, at speeds exceeding 13% of the speed of light, the fusion energy becomes only a small addition to the energy of the incident particles. The scoop has to gather the hydrogen with essentially no loss of energy whatsoever (that is, nearly zero drag). This is problematical for charged particles, which emit bremsstrahlung when decelerated (and of course neutral particles aren’t affected by fields and can’t be collected by any of the collector designs proposed). All of the collection devices suggested produce more drag than thrust (this is why Eder and Zubrin proposed using the collectors as decelerators, the “magsail”). The problem gets worse approximately as the square of the speed.

Arguably the hardest of these is the p-p fusion, a process that we don’t know how to do, and is simply assumed. At the center of the sun, at 15 million degrees C, p-p fusion does occur. At this temperature, the thermal radiation is in the form of x-rays at about 10^20 W/m^2… none of which can be allowed to escape. And here the fusion rate of an average hydrogen atom is roughly one fusion per billion years.

The final problem, turning fusion into thrust, seems almost trivial by comparison, although it is also unsolved (the fact that the reactor has to allow ions to enter the reactor, as well as leave, makes this difficult).

The difficulty is that all the proposed solutions to the many difficulties make the problems worse. The CNO cycle proposed is a perfect example of making the problem worse. The CNO cycle only takes place in massive stars, because it requires higher temperatures than simple p-p fusion. It also includes a rate-limiting step of 13N decay, with a half life of 10 minutes. And the catalysts, C, N, and O, significantly outweigh the hydrogen in the cycle, but can’t be collected from the interstellar medium, and hence can’t be left in the exhaust.

About the best summary of the Bussard ramscoop idea is that it doesn’t actually violate the laws of physics, but it includes steps that not only do we not know how to do yet, we don’t even have approaches to doing that work in principle.

The numerous technical problems you point out are why the website is called Centauri DREAMS.

Geoff

I will repeat my comment for elsewhere here.

(I would ask this question, have you ever read the Fishback paper?

Yes all those are problems but to you think those are problems that could not be solved by a K2 civilization?

Interesting objects moving in high density regions of the galaxy , maybe?)

…. my sense of things is that only a K2 civilization could build one … my further sense is that the engineering physics is so much trouble that one has never been built , there are easier ways (tho still hard to do). Like you say basic physics does not preclude it, tho the strength of materials does limit the Lorentz factor as Fishback shows. Fishback does derive an equation of motion with drag , synchrotron and bremsstrahlung losses in the scoop field and shows the ship can accelerate or at least he gives the conditions for it. Tony Martin’s papers are important too in this regard. The fusion reactor is also probably K2 level. It’s super science for sure but Fishback’s paper seems to get lost in studies of the ramjet, and there really are not that many studies of the ramjet since Dan Whitmire wrote about the catalytic ramjet.

Yes doing the CNO cycle is way beyond our technology probably for the next 500 (1000?) years, but I would not put it past a K2 civilization.

“My rule is there is nothing so big nor so crazy that one out of a million technological societies may not feel itself driven to do, provided it is physically possible.”

— Freeman Dyson

“Yes all those are problems but to you think those are problems that could not be solved by a K2 civilization?”

Kardashev civilization levels are defined by the amount of energy they control. A K2 civilization, controlling energy equal to the output of a star, about 10^26 watts, would have little or no need for mere fusion at levels of a few gigawatts.

But I think that the statement “we don’t know how to do this even in principle” is only poorly addressed by saying “well, if we knew how to do things we don’t have any idea how to do, we could do it.”

Originally Kardashev defined I, II and III level civilizations were defined in terms of how much energy they could bring to doing communication by electromagnetic or such-like means. However for Type II … any civilization that has mastered capturing all the energy from their local star for use will have mastered a myriad of other instrumentality’s. Whitmire shows that a CNO fusion reactor would need temperatures = 86 keV, number density = 5 x 10^19 cm^3, and confining magnetic fields = 1.8 x 10^7 G , way beyond any engineering physics we know, still engineering physics a K2 might do. My sense of things is also that K2 don’t build these reactors. I further think that if they do interstellar flight , if they do, they will have found ways to finesse the problem with much more subtlety. I think at the most fundamental level of knowledge a K2 will have mastered is the life sciences so well that individual life times (if they still have them) will be on such long time scales that their approach to interstellar travel will be with a billion times more patience current human civilization has.

There is no mention of the study that suggests that the drag would be greater than the thrust. Have I been led astray by this idea that supposedly invalidates the ramjet concept?

While I haven’t read up on the use of antimatter that uses the ISM, I do recall reading about the various ratios of matter:anti-matter for different mission types. The farther and faster you want to go, the more equal the ratio. For an interstellar flight, with a 50:50 ratio, the ISM would only cut the mass ratio by 1/2. For interplanetary flight, with much higher matter:anti-matter ratios, it suggests that the solar wind might make a good source of matter for the propellant. As with the laser propelled sails for interstellar travel of the probes, the easier and possibly more interesting near term application is for solar system flight. We might aim for the stars, but we gain the solar system in the meantime.

There is mention of drag. This is one of the things John Fishback worked out. He takes account of charged particle mirroring in the magnetic scoop field and particles that make it into the reactor. These processes are accounted for in the equations of motion and Fishback derives the conditions for acceleration. Tony Martin’s papers, listed above, also re-derive , a little more clearly, the conditions of mirrored charged particles, because it is mirroring by the magnetic scoop field that is the energy loss and leads to drag. John Fishback and Tony Martin’s papers have drag covered. How one would do the engineering physics of this , man!, it is far future technology, or the technology of an advanced civilization.

I’ll take the big old fashioned laser on Earth, and then more lasers spaced outward as far as we can get them (driven by some kind of nuclear power plant I guess so they last a long time) hitting a large light sail and driving whatever mass we can manage, up to a significant fraction of c for the next couple of hundred years. It gets our probes out to nearby star systems and if we can decelerate we can get a good look at whatever planets are there. That would be an amazing era to live in (i.e. when the probes actually arrive and start transmitting data). As for Bussard’s idea could the ram scoops be made much, much bigger since the interstellar hydrogen density is much lower than he hypothesized? We’re going for an idea in the far future anyway so might as well try to scale up :).

I sure hope I don’t embarrass myself because of my youth and inexperience, having been born in 1963 and knowing Bussard’s journal article was published in 1960, big however sigh coming…I have published two journal articles in Acta Astronautica. Paul even watched me fumble my way through one at a conference. If they changed the journal’s name or it’s a completely different journal that no longer exists, then I must have missed something on that dang clicky click thang those whipper snappers call the internet.

I remember your paper and you hardly fumbled your way through it! Anyway, in 1960 the journal was indeed Astronautica Acta. I don’t recall just when that changed to Acta Astronautica, but I’m thinking some time in the 70’s? Someone will know. Al?

Thank you Paul! I may be young and inexperienced, but as Muhammad Ali would say “I’m still a pretty man.” ;-}

Acta Astronautica was first published in1955 as the official Journal of the International Astronautical Federation (IAF) with the title Astronautica Acta.

In 1962,the Astronautica Acta became the official Journal of the International Academy of Astronautics (IAA) established in 1960.

In 1974, the title changed to Acta Astronautica for the sake of

proper grammar.

In Latin, word order is not of grammatical importance. Acta Astronautica and Astronautica Acta are the same thing.

True enough, Geoff, but the bibliographer in me wants to know when the switch was made. It’s a compulsion, like remembering when Astounding went to Analog and how long Campbell used the twin logo trick.

The remark about proper grammar was not mine, I would not know. It is from a paper in Astronautica Acta, “Entering the 60th year of Acta Astronautica”, by Chang ,Chern and Jean-PierreMarec, Acta Astronautica 97 (2014) 172-193……

Campbell had always wanted to change the name from Astounding … he did so in 1960.. in an editorial he said he always thought ‘Astounding’ sounded too pulpish , like ‘Flabbergasting’ , he took over the editorship in 1938 and made Astounding as far apart from the then Pulp SF magazines as he could. I don’t know if in those days he ever approached Street and Smith about changing the name.

Al, I was responding to Geoff Landis on the grammar statement, not you. I have all those old Astounding issues when the transition was going on to Analog, and it was fun to watch how they handled it.

A K2 civilization could use the CNO process which happens in large stars at very high temperatures and pressures. It uses the triple alpha process. A civilization which has metal element fusion capability would not need to use an inefficient interstellar ram jet. A fusion rocket can have a very high specific impulse over 100,000, so why would one need an interstellar ramjet? An matter anti matter drive has a specific impulse of half to three quarters the speed of light.

There is no evidence that there is any negative energy in a Casimir cavity which only has less energy than the surrounding zero point energy outside the plates. The Casimir effect is only a crude analogy of negative energy to show that there can be less zero point energy than than average which makes the idea of negative energy possible. Consequently, a Warp drive can’t be constructed out of a Casimir cavity. Fusion reactors and matter anti matter annihilation have the energy needed to make a warp drive.

Geoffrey Hillend

“The Casimir effect is only a crude analogy of negative energy to show that there can be less zero point energy than average which makes the idea of negative energy possible. Consequently, a Warp drive can’t be constructed out of a Casimir cavity. Fusion reactors and matter anti matter annihilation have the energy needed to make a warp drive.”

I was under the impression that this particular type of warp drive didn’t require the application of negative energy but rather it required something called negative matter or something called exotic matter to create the warp effect. I’m sure that I’m stating the problem incorrectly and not using the proper terminology but I think it had something to do with a minimum energy condition that had to be satisfied by the equations of general relativity. But again I’m not certain of the particulars of the problem. Anyone out there who could shed some light on this problem?

The Casimir effect seems like an absurdly complicated explanation for some simple physics. As I understand the traditional story, there are “virtual particles” everywhere … except where a conductor doesn’t allow them to exist… and the force is caused by the absence of these virtual particles due to current that could flow if they were there.

The explanation I prefer – it’s in the Wikipedia article, cited to some rather challenging preprints – is that the force between the plates is simply a case of the Van der Waals force, or dispersive force, between two conductors a bit larger than the usual electron density cloud. If it works for atoms, why not groups of atoms? But if this is so, there is not a whiff of negativity in the air (except where charge is concerned) – which is why physics is better than politics.

This is a good point. It is important to realize that our mathematical models of nature are not nature, just useful models. That a current is said to flow from a positive potential to a negative potential does not imply the existence of a charge “hole” in list of fundamental particles. When a virtual particle pair appears at an event horizon and one of the pair falls in we may say that negative energy is added to the black hole. Similarly the mathematics of relativistic dynamics allow for tachyons even though there is no fundamental justification for their existence. Et cetera. So it is not too surprising that some choose to burden the Casimir effect with unrealistic expectations.

In terms of General Relativity, it doesn’t matter if you model the Casmir vacuum as a negative energy vacuum or simply as an attractive force in the empty space between the plates. An attractive force would be a negative pressure in the stress-energy tensor (albeit an anisotropic negative pressure), and negative pressure behaves like negative energy for the purposes of the Einstein equation.

Michio Kaku gives a more realistic specific impulse for an anti matter rocket or one to ten million and a maximum of two hundred thousand for a fusion rocket. P. 141, The Future of Humanity

To be direct, I don’t think there is any such thing as negative matter, but I do think there is negative energy and negative mass. Physicists and propulsion scientists are interested in designer space times using general relativity, and it seems to me that the idea of negative matter might have a practical payoff in that one could control it better or not have to worry about the problems of generating negative energy. For example; The energy conditions or quantum inequality law states that in order to make negative energy, one always has to have more positive energy. I don’t think that law can be broken based on quantum field theory. Consequently, there are series problems with the idea of negative matter being found somewhere naturally in space. Negative matter being compared to normal matter is a good example. A palm held size rock of normal matter does not have very much gravity; it does not emit much gravity waves so one needs a lot of it to have a weak gravitational field. The problems begin when one considers what could negative matter be made out of? It can’t be made of negative energy which does not clump together like ordinary matter. Also the positive energy in normal matter is locked up in the electromagnetic and strong nuclear forces so it would take energy, a lot of it to free those forces. A strong field of negative energy would draw energy from the negative matter or positive matter.

Also I have to admit I and using my scientific intuition to rule out what seems more imaginary from what potentially can’t exist using invariant principles and conservation laws. It says in the appendix of the book The Quantum World, the graviton has zero charge, zero spin, and zero mass and gravitons are their own anti particles. It’s easy to conclude the anti graviton is a force particle with the same qualities, but it expands space instead of contracts it. By plugging into scientific principles, I hope rule out all the speculative ideas and what is left over is real, and what is real can’t be invalidated. In otherwords, I assume that all the so called problems with the warp drive and faster than light can be solved if we rule out the ideas that say it can’t be done using thought experiments and scientific principles.

Its this particular confusion on the part of general relativity that creates a lot of uncertainty as to what should be done exactly in regards to creating faster than light drives. Should in fact there be needed to have some type of exotic matter to create the necessary conditions for this to physically occur ? This is some of the questions that I have had concerning how the general relativity theory fails to address what needs to be satisfied to permit this to have realization in the real world.

Regarding negative matter, see https://arxiv.org/pdf/1809.09615.pdf – apparently the ANITA project to detect cosmic rays in Antarctica has had the odd issue that some of them keep coming up out of the ground. So far all that the physicists are willing to say is that this is probably “beyond the standard model”, but disencumbered of such wisdom I can feel free to ask whether a particle with a small negative mass, colliding with the Earth at great speed, might result in a shower of normal particles that satisfy conservation of momentum by moving in the opposite direction.

The Quantum World is by Kenneth W. Ford. Since negative energy causes space to expand, I don’t see how it could hold together or clump together to make some kind of matter. Anti matter has positive energy density so it still clumps together by the attractive force of gravity, but negative energy has negative energy density.

If as a species we are to achieve interstellar flight of whatever kind I have a few ideas about what needs to occur before that happens (unless we want to act out our behaviour in Avatar or our historical behaviour in the European invasion of North and South America for example).

1. Reduce the human population by at least an order of magnitude to reduce our damage to Earth’s fragile ecosystems. This requires at the very least:

2. All children receive a good education. It has been shown repeatedly that more educated countries in general have much lower birth rates.

3. health care for everyone. Who knows how many geniuses have been lost due to tragic deaths from preventable or curable illnesses? Everyone deserves the same quality of health care.

4. a recognition that unbridled capitalism is destructive and unrealistic in the long run. It doesn’t work any better (and in fact probably much worse) than communism. Trillions of pieces of discarded plastic in the oceans is an example of a throw away society. An island of plastic the size of France in the Pacific Gyre.

Do we want to go to the stars? We had better start by learning how to live right here on Earth first.

While these are all laudable goals none are prerequisite to interstellar travel.

With respect Ron, survival as a planetary civilization might be a prerequisite to interstellar travel. Descent into fascism and barbarism might not work out so well as far as allowing for the technological advances required for such huge efforts to succeed. We don’t seem to be headed toward a stable civilization capable of sustaining the huge effort required for travel to other star systems (even discounting the current pandemic which is being poorly managed at the highest level it seems).

Survival of civilization is prerequisite to everything! Your mistake, in my opinion, is believing that if your stated ideals are not achieved that our civilization will end. We’ve come this far with poor adherence to those ideals and I see no reason for progress not to continue. Again, that does not mean your goals are not laudable, only that they are not necessary. There is a multitude of potential pathways that do not lead to global apocalypse, or at least not before we achieve interstellar flight.

Thank you for your comments Ron. I’m thinking hard about them and Alex’s. I’m not sure you’re right and I’m wrong. We’re doing the experiment and the answer will come out one way or the other whether we like the outcome or not. We are not old as a species. About 200,000 years as modern humans or roughly ten thousand generations. In that time we have reached a point where we are predicted to cause the extinction of a million species in the coming years. We need a drastic change and I don’t see it even beginning yet. Species that can’t change from a disastrous course can have a disastrous ending. I hope not but I fear far too few people are willing to make the changes required, especially those in power. I do enjoy reading both you and Alex’s comments. You are clearly experts in your fields and very clearly much more intelligent than I am but I still worry…..

That would immediately reduce the economy by 90% if done randomly, and a lot more if the worst polluters were selected first. As an interstellar species needs a large supporting economy, this will set back the potential for interstellar travel. Most likely we will need a solar system wide based economy, even if this is mostly robotic. Perhaps we end up like Asimov’s Solarians (“The Naked Sun”) with a large population of machine slaves instead of human slaves as we once did. I would be disappointed if we had to choose between preserving the Earth and galactic space faring, but that is possible.

No. Communist countries were far more polluted that western democracies as there was no incentive to maintain a clean manufacturing base. Just compare East vs West Germany. The Chernobyl disaster, whilst a one-off caused far more damage than nuclear incidents in teh west, even Japan’s Fukushima meltdown.

I would argue that it is the demand for lax regulations and little oversight that is the main cause of our problems, not capitalism as a system. We could change the rules to make it work far better if only we could wrest our legislators from its influence. As for other political and economic systems tried in the past, history is littered with their environmental impacts due to lack of knowledge and poor restraint. Jared Diamond’s “Collapse” is an easily accessible book to provide a glimpse in the problems cultures have had in teh past and which ones maintained their environment compared to those that destroyed it, and ultimately their own culture with it.

I see “going to the stars” and “learning to live with planet Earth” as orthogonal issues. We can do any combination of the two. If we had to drastically scale back our human population and economic systems to protect Earth, then I would suggest that this will make going to the stars less reachable unless we can find some way to compensate for the downsizing.

In the nation where I live – Norway – we were too many in the second half of the 1800s. North America became the solution for about 50% of us.

It is very difficult to determine carrying capacities for humans as we can do things that nature cannot. As we pack ourselves into cities and find better ways to grow and make food, it is quite possible we could even increase our populations by largely abandoning traditional farming, and even allow rewilding to replace farmed acreage. Reducing wastes and recycling far more efficiently will also be required. But unless we are concerned about falling back into a pre-industrial way of life with similar technology, I see no inherent reason why we should revert to some Malthusian limits with a lower population level. But it does mean we do have to change our current methods and it is the risk that we do not where I see the problem of maintaining a population of perhaps 10 billion later this century. The upside is that a well-nourished, educated, global population with access to information and technology could expand our economy and potentially bring forward our development as a space-faring, even star-faring, species assuming that is the direction we take.

My prediction, for what it’s worth is that we won’t make it to ten billion. We are struggling now with about 7.5 billion. Never underestimate the human capacity for greed and stupidity. A reduced human population which is adequately fed, educated, loved, and housed would allow for many laudable goals to be achieved. Yes, it is difficult to estimate the Earth’s carrying capacity especially when many members of the human race have short term goals centered around their own wealth. We have about 50 years left to drastically change our way of life (10 years until climate change becomes irreversible and in fact begins to become a runaway greenhouse effect). Many humans seek to remove all limits to their own greed. I can think of many in power right now who do so. I see Limits to Growth as the basis for learning how to proceed as well as its successor Beyond the Limits to Growth. Endless growth is the basis of most economic theory but the Earth has finite limits. How much did our economy grow this year? Isn’t that always economists main concern? If we’re talking about saving ourselves with a space economy I think we had better save as much of the Earth as we can to get there.

At the risk of going too far off-topic, it isn’t “the economy” per see that is teh problem, but how humans decide to create it.

Life has been growing its economy, with some setbacks, for over 3.5 bn years. The “profit” in this case is increasing biomass as ever more niches are exploited with ever more diverse forms. Only recyclable materials are allowed in this economy.

In contrast, humans have opted for an extractive economy where the material is mined, manufactured, and discarded, using mostly mined fossil energy. Our post-industrial economy has shifted increasingly to non-manufactured, intellectual goods. Until the bronze age, we had an economy that was effectively fully recyclable.

With an economy that moves increasingly to intellectual goods and services, we can continue to grow the economy just as life does, with the increasing diversity of intellectual products our proxy for life’s growing diversity.

While I don’t believe we can forego extraction and manufacturing products, but we could use, indeed we must use, only solar energy if we are to become a K2 civilization. With energy abundance, we can recycle everything, however inefficient that recycling is. Recycling everything will require we change a lot of our current crude practices. Whether we can do that is problematic, and as you say, human greed and laziness will tend to stymie our efforts.

In some ways, it is disheartening to read the same old arguments of the “colonize Mars to start again” true-believers that we had back in the 1970s, despite the knowledge we now have of our planet and how we require its myriad processes. It is almost like we are reverting to the simplistic, libertarian ideas of Heinlein novels. However, I do not want our civilization to reject expansion, even if it proves limited to the solar system. Without some way to maintain the sort of civilization implied in ST:TOS, we will likely revert to the historically more stable, authoritarian, hierarchical political and social systems. We are primates, and this is embedded in our genes over millions of years of evolution. It takes a lot of effort to overcome this.

On good days, I’m hopeful we can do this. On bad days…

Well said Alex. Let’s hope we get it right. It starts with people agreeing that change is absolutely essential. Meanwhile, on a lighter note I continue to feed the birds of the area, drive an electric car to buy our food, and harvest solar energy with our solar panels. (over 2 Megawatt hours in less than 5 months to date). All the best to all of our friends to the south. Canadians stand with you. We send many nurses to work in Detroit hospitals every day and we continue to strive to keep our trade in essential goods and services open in both directions.

A silver lining that may come out of the current Covid-19 pandemic is the realization that all that fossil fuel powered travel isn’t necessary. Many people can work from home as once predicted. That frequent air travel “for business” isn’t necessary. I can see that using robot avatars might even substitute for high touch services (see movie Sleep Dealer or less realistically, Surrogates) . I wouldn’t propose having a world as cooped up as E. M. Fosrter’s The Machine Stops but clearly we have options. There does seem to be a revival in watching webcams of places, ans I could definitely see a place for avatars to replace personal physical presence in a host of situations. OTOH, people do seem to have short memories, so maybe it will be back to business as usual in a few years. What will it take to really change things? One small light in this direction is Amsterdam to embrace ‘doughnut’ model to mend post-coronavirus economy.

It seems to me that it’s an open question regarding which type of society is best at accomplishing long term, very expensive projects requiring technological breakthroughs. After the moon landings and the end of the Cold War, capitalistic economies regulated by democratic governments seemed to be the obvious winner. But the rise of China with their one party system makes the answer less clear.

Excuse me the graviton has a spin of 2 according to The Quantum World, I wrote zero spin which is a mistake. It shows the graviton has zero charge , zero mass, and spin 2, and anti particle is itself. p. 256.

Odd problem. Some papers published in Acta Astronautica are found in searches (Whitmire for example) whereas others (Martin) fail. Perhaps this is a function of the publication vintage but it would be nice to access the papers.

Yes. Bussard’s paper seems to have been OCR’ed in or typed in and put on the net , there is a link:

https://web.archive.org/web/20180417180616/http://www.askmar.com/Robert%20Bussard/Galactic%20Matter%20and%20Interstellar%20Flight.pdf

but beware there are typos in this in the equations, equation 24 is repeated as equation 25 for instance.

Dan Whitmire’s paper is also here:

http://www.askmar.com/Robert Bussard/Catalytic Nuclear Ramjet.pdf

That one too has some typos in the equations.

I don’t know if Acta Astronautica has scanned in back issues yet are not.

The BIS has not scanned in all the JBIS issues tho that is their plan.

Some libraries have hard copy of the journals.

Looks like Fishback’s father also killed himself:

https://img.newspapers.com/img/img?institutionId=0&user=0&id=107330554&width=557&height=463&crop=0_6105_1837_1557&rotation=0&brightness=0&contrast=0&invert=0&ts=1586136935&h=677b3386767665a6926f57b496934ddf

That is interesting , I did find an obit for John Fishback in a Kentucky newspaper. Seems the Fishbacks were known in Kentucky but have not been able to trace them.

There does seem to be an imperfect, but disturbing correlation between brilliance and mental illness/suicide. Ted Kaczynski comes to mind, but it’s an insult to Fishback to compare the two.

Is there any general idea of what kind of speed range such a craft might have? And minimum speed relative to the medium required for ‘ignition’?

Charlie, FTL propulsion does not violate general relativity which actually has made FTL possible since negative energy is what needed to make FTL propulsion, and if it was not for general relativity, we would not know anything about the possibility that there could be potentially such thing as negative energy and without the idea of negative energy, anti gravity would not be possible. The faster than light idea came first through the imagination.

Negative energy would be an invisible field which warps space just like gravity. There is the idea that the field might also might need to be connected to some kind of matter or solid object which emits a negatively warped field which expands space with a repulsive force like Cavorite in the science fiction movie, the First Men in the Moon. I think that the exotic matter idea is like Cavorite or is science fiction or a myth. IF we can invalidate and idea using scientific principles, it probably is a myth. The concrete mind wants to anchor and catch ideas in form and boundaries. Sometimes it concretizes things which should not be concretized. Since gravity comes from all matter, it is natural and logical to assume that there should be some kind of solid negative matter which emits negative energy waves and creates a field of negative energy surrounding it. So far there is no observational evidence of negative matter in our universe and all of the matter we know and see is bayonic matter. A gravitational field is not a solid mass but is made of wave particles which don’t have mass, but only energy.

All baryonic matter which is composted of three quarks has positive energy density, so it emits gravity waves and makes a gravitational field. Gravity contracts space with an attractive force. This is according to Einstein’s general relativity which states that matter and energy warp space and that warp is gravity. The warp curves space time, but space can be curved in more than one direction. For example gravity contracts space, so two perfectly parallel straight lines will converge, but an anti gravity field would do the opposite two straight lines or light beams would diverge traveling through a negative energy field. General relativity only says that space will curve, but how you want it to curve is dependent on the type of energy one puts in the space according to Einsteins curvature tensor. Miguel Alcubierre noticed that. Consequently, Negative energy does not violate general relativity which is always predicts how mass move through space and how a large amount of mass energy warps or curves space-time.

General relativity is intrinsically part of physical reality itself, so what is not supported by general relativity does not represent a physical reality, but is more imaginary. The same thing is true about quantum field theory which is why scientific first principles are considered to be mind independent and objective and why these systems of principles are physical laws work everywhere in our universe.

What I would like to know is if the graviton and anti graviton both have the same spin of 2, zero mass and zero charge, how are the different? How can we distinguish them? Why should the graviton warp with positive curvature and the anti graviton warp space with negative curvature but both of them can still have the same spin, and no mass or charge? Maybe a quantum theory of gravity will add some new features which distinguish them which is why I hope scientists will continue the search for the graviton with the LHC when it comes back online in May 2021.

I’m straying from the topic a bit, but I have to ask: has anyone proposed neutrino pair production as an energy source and/or propellant? Neutrino mass is less than 0.120 eV/c^2, and each neutrino produced at (for example) room temperature should carry 8.6E-5 eV/K * 300K * 3 = 0.079 eV of thermal energy. If the mass of one flavor turns out to be a lot less, maybe you could carry away much more thermal energy than it takes to make the neutrino. Ideally such a device might be used for cooling an area without appearing to pump the heat anywhere else (a true portable air conditioner), and maybe the heat difference could drive a thermal engine to recover the energy to make the neutrinos? The other question of course is whether you could send them both out at a high speed in one direction with reaction force on some other particle. This (I dub thee, I dunno, Gemino Drive) might have advantages as a propellant by comparison to a photon drive.

I’ll admit that everything I found about neutrino pair production last time I went over this one was very, very discouraging, but still … I wonder. Anyone working on it?

This is a particular question directed at Dr. Jackson.

I wonder is whether or not the question of having increasing acceleration by the ship is as crucial a matter as it might first appear. For example given there is a limitation in the hoop strength for the magnetic field, then the fact they cannot go above that particular hoop strength – is that really a show stopper ?

Even though there would be a limitation to how much outside matter flow rate could be imported into the ship’s reactor, would such a restriction prevent you achieving a change in velocity, not as rapidly as you would wish, but still being able to have as high a ultimate velocity as you wish but at a much lower rate.

Wouldn’t that be just as acceptable in this scenario as one where you would require greater and greater amounts of fuel to compensate for the mass increase of the ship ? I realize that the ques. is awkwardly worded.

Hi Charlie

Yes Fishback pointed out that one could accelerate taking into account the stress on the sources of the magnetic scoop field. Tony Martin quantified this and corrected a numerical error by Fishback. I wrote about it a little here:

https://www.lpi.usra.edu/lpi/contribution_docs/LPI-001977.pdf

(I plan to expand this paper and publish it someday.)

One notes that the acceleration profile drops very low after the stress limit is hit. Fundamental physics , I mean at the atomic level , limits the ultimate shear modulus of a material [1]. This limit implies an ultimate limit of a Lorentz factor of about 10,000, that is .9(bunch of 9s) percent the speed of light. A K2 civilization might be able to beat with limit with unknown engineering physics. (One always has to temper such comments… to paraphrase Issac Asimov…”There maybe engineering physic we know nothing about, but, we know nothing about it!”)…. I don’t think civilizations are sending out star ships with gammas of 10,000 (maybe ways to beat this with STL ships propelled in other ways). Way below this limit one has to deal with problems like the radiation processes produced in scooping, or worse, running into interstellar dust , or worse! It is interesting that Poul Anderson explicitly mentions these problems in Tau Zero and gives a somewhat non- Techno-Babble-yet-tenable-sounding explanation of the engineering shielding physics involved. (I wish movies and TV SF could do this.) ….

[1] W. H. Press and A. P. Lightman , Dependence of macrophysical phenomena on the values of the fundamental constants, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series A. ,Vol. 310, No. 1512, Dec. 20, 1983 ( A very clever paper.)

ques. Al,

in your paper :

https://www.lpi.usra.edu/lpi/contribution_docs/LPI-001977.pdf

you say :

“Graphene is close to the upper limit on the maximum tensile strength of a material; however it is possible the theoretical limit may be extrapolated to a limiting Lorentz factor to 10,000. (Note the material Carbyne is approximately twice as strong as Graphene.)”

Is Carbyne a fictitious material?

Sorry for late reply. Carbyne (Linear acetylenic carbon) is real and has twice the tensile strength of Graphene. However using the method of Press and Lightman (above) one gets an ultimate strength for ordinary matter (not something like Neutron Star Matter, say). That implies a Lorentz factor of about 10,000 , which would be monstrously large for a relativistic starship. For slower than light ships …Lorentz factors much less than this would suffice for interstellar travel.

It would seem to me that Jupiter would be the perfect place to launch the Interstellar Ramjet from, with its thick hydrogen atmosphere. ;-}

https://www.missionjuno.swri.edu/news/high_altitude_hazes_on_jupiter

But, it seems that somebody has already beat us to it!

Hmm, looks a bit like con-trails.

Michael,

Jupiter (or another gas giant, or ice giant planet) might make not only an ideal launch site for a ramjet starship or starprobe (starting from a close, atmosphere-grazing orbit [even at least some the the initial internal, “boost fuel” could come from the jovian atmosphere, perhaps collected via an electrostatic tether]), but also a desirable test site for developing the technology. (Think of it as the “Edwards Air Force Base” of fusion ramjet spacecraft.) Now:

Before we send off an interstellar probe–let alone a starship of any kind, even a “seedship”–to another star, the technologies of ramscoops, their electromagnetic and electrostatic field systems (and ^their^ control systems), and their “fast-burn” (or catalyzed reaction cycle) fusion reactors will need to be developed and perfected. Ramscoops can also be utilized as braking devices against the positively-charged solar wind and stellar wind particles (for starships in particular, the former would come in handy when returning home to our Solar System). But the required fields, and their control devices, will need some R & D work first, even before a fusion reactor is added to the mix, so: