I had never considered the possibilities for life on Uranus until I read Geoffrey Landis’ story “Into the Blue Abyss,” which first ran in Asimov’s in 1999, and later became a part of his collection Impact Parameter. Landis’ characters looked past the lifeless upper clouds of the 7th planet to go deep into warm, dark Uranian oceans, his protagonist a submersible pilot and physicist set to explore:

Below the clouds, way below, was an ocean of liquid water. Uranus was the true water-world of the solar system, a sphere of water surrounded by a thick atmosphere. Unlike the other planets, Uranus has a rocky core too small to measure, or perhaps no solid core at all, but only ocean, an ocean that has actually dissolved the silicate core of the planet away, a bottomless ocean of liquid water twenty thousand kilometers deep.

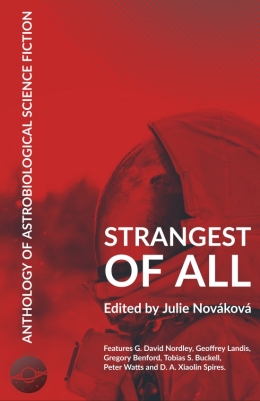

It would be churlish to give away what turns up in this ocean, so I’m going to direct you to the story itself, now available for free in a new anthology edited by Julie Novakova. Strangest of All is stuffed with good science fiction by the likes of David Nordley, Gregory Benford, Geoffrey Landis and Peter Watts. Each story is followed by an essay about the science involved and the implications for astrobiology.

Although I’ve been reading science fiction for decades, our discussions of it in these pages are generally sparse, related to specific scientific investigations. That’s because SF is a world in itself, and one I can cheerfully get lost in. I have to tread carefully to be able to stay on topic. But now and then something comes along that tracks precisely with the subject matter of Centauri Dreams. Strangest of All is such a title, downloadable as a PDF, .mobi or .epub file. I use both a Kindle Oasis and a Kobo Forma for varying reading tasks, and I’ve downloaded the .epub for use on the Forma, but .mobi works just fine for the Kindle.

What we have here is a collaborative volume, developed through the European Astrobiology Institute, containing work by authors we’ve talked about in these pages before because of their tight adherence to physics amidst literary skills beyond the norm. The quote introducing the volume still puts a bit of a chill down my spine:

“…this strangest of all things that ever came to earth from outer space must have fallen while I was sitting there, visible to me had I only looked up as it passed.”

That’s H. G. Wells from The War of the Worlds (1898), still a great read since the first time I tackled it as a teenager. What Novakova wants to do is use science fiction to make astrobiology more accessible, which is why the science commentaries following each story are useful. Strangest of All looks to be a classroom resource for those who teach, part of what the European Astrobiology Institute plans to be a continuing publishing program in outreach and education. We’ve talked before about science fiction’s role as a career starter for budding physicists and engineers.

Gerald Nordley’s “War, Ice, Egg, Universe” takes us to an ocean world with a frozen surface on top, a place like Europa, where the tale has implications for how we approach the exploration of Europa and Enceladus, and perhaps Ganymede as well. In fact, with oceans now defensibly proposed for objects ranging from Titan to Pluto, we are looking at potential venues for astrobiology that defy conventional descriptions of habitable zones as orbital arcs supporting liquid water on the surface. Referring to characters in the story, the EAI essay following Nordley’s tale comments:

Chyba (2000) and Chyba & Phillips (2001) tried to work even with these unknowns and calculate the amount of energy for putative Europan life, and to describe what ecosystems might potentially thrive there. According to these estimates, even a purely surface radiation-driven ecosystem might yield cell counts of over one cell per cubic centimeter; perhaps even a thousand cells per cubic centimeter in the uppermost ocean layers. Putative hydrothermal vents, of course, would create a different source of energy and chemicals for life (albeit one much more difficult to discover – in contrast, life near the icy shell might erupt into space in the geysers and be discovered by “simple” flybys). Any macrofauna, though, seems highly improbable given the energy estimates. Since Loudpincers was about eight times larger than the human Cyndi, by his own account, we’ll really have to look for his civilization elsewhere, perhaps on a larger moon of some warm Jupiter.

You see the method — the follow-up essay explores the ideas, but goes beyond that to provide references for continuing the investigation in the professional literature. This essay also speculates about Ganymede, where a liquid water ocean may be caught between two layers of ice. The ‘club sandwich’ model for Ganymede posits several layers of oceans and ice, which would make Ganymede perhaps the most bizarre ocean-bearing world in the Solar System, one with incredible pressures bearing down on high-pressure ice at the bottom (20 times the pressure of the bottom of the Mariana Trench on Earth).

Gregory Benford’s “Backscatter” is likewise ice-oriented, this time in the remote reaches of the Kuiper Belt and the Oort Cloud beyond. From the essay following the story:

Although it’s difficult to imagine a path from putative simple life in early water-soaked asteroids heated by the radioactive aluminum to vacflowers blooming on the surface of an iceteroid, life in the Kuiper Belt, the Oort Cloud and beyond cannot be ruled out – and we haven’t even touched the issue of rogue planets, which might have vastly varying surface conditions stemming from their size, mass, composition, history and any orbiting bodies.

The essay gives us an overview of the science that, as in Benford’s story, conceives of possible life sustained by sparse inner heat and the presence of ammonia and salts, perhaps with tidal heating thrown in for good measure. Cold brines would demand chemical and energy gradients to sustain life, a difficult thing to discover or measure unless cryovolcano activity coughs up evidence of the ocean below the ice. Some silicon compounds may support a form of life in ice as far out as the Oort, or perhaps in liquid nitrogen. Usefully, the essay on “Backscatter” runs through the scholarship.

The European Astrobology Institute has put together a project team around “Science Fiction as a Tool for Astrobiology Outreach and Education,” out of which has come this initial volume. The references in the science essays make Strangest of All valuable even for those of us who have encountered some of these stories before, for the fiction has lost none of its punch. Thomas Bucknell’s “A Jar of Goodwill” looks at new forms of plant metabolism on a world dominated by chlorine and a key question in addressing alien life: Will we know intelligence when we see it? Peter Watts’ “The Island” looks at Dyson spheres in an astrobiologically relevant form that Dyson himself never thought of (well, he probably did — I bet it’s somewhere in his notebooks).

All told, there are eight stories here along with the essays that explore their implications, an easy volume to recommend given the EAI’s willingness to make the volume available at no cost to readers. See what you think about the Fermi paradox as addressed in D. A. Xiaolin Spires “But Still I Smile.” Plenty of material here for discussion of the sort we routinely do here on Centauri Dreams!

Ahem. If Uranus was a water world as described, shouldn’t it be in the HZ. Clearly it is not.

Uranus describes this mantle as:

The base of the troposphere seems quite clement, even if somewhat under high pressure:

If we care about surface liquid oceans as an abode for life, why do we exclude such worlds? Could we, even in principle detect biosignatures on such worlds?

When Gerard O’Neill introduced teh idea of space habitats, I recall that Asimov said that assuming we needed planets to colonize was “planetary chauvinism”. Is the exclusion of outer planet worlds like Uranus a case of classic HZs being influenced by “rocky planet chauvinism?”

“Uranus’ core density is around 9 g/cm3, …”

ONLY 9 g/cm3 !?! Seems kind of low …

Hi Alex,

There’s a recent suggestion from the latest modelling is that Uranus might actually be *solid* beneath the H2/He layers:

Thermal Evolution of Uranus with a Frozen Interior

Nestled between that solid core and the clouds, it’s entirely possible there’s an distinct boundary due to a miscibility change in the Water/Hydrogen mix.

Hi all

Good points, I was thinking this too, an ocean is much more likely on Planets between 3-to say 8 Earth masses with a much smaller atmosphere, (Super Earths/Mini Neptune planets) when you get the masses of Uranus/Neptune it would be high pressure hot ices under the He/H atmosphere

At TVIW in 2019 there was this topic:

Preparing for First Contact: Protocols and Implications

A Seminar/Working Group

“First contact scenarios are fairly common in Science Fiction. But, what would we do, what should we do, if we actually encountered intelligent, perhaps very advanced, aliens in real life?

On the scale of the universe, or even our galaxy, our physical “encounter cross section” is very small, but it is increasing as we begin to send probes and eventually humans throughout the solar system and beyond. Also, our technological ability to detect alien signals and other artifacts is booming. Thus, though our chances of an encounter are very small, they are not zero and indeed are increasing. In the world of risk management, potential events are commonly rated in terms of probability and impact. In these terms an alien encounter is not very probable but the impact could be beyond measure and therefore must be taken seriously. In that vein, it is worth the relatively small effort to plan ahead on how to handle an encounter rather than be forced to “wing it” when the potential downside risk of a miscalculation extends to human extinction.

In this seminar/workshop we will start with overview talks from a very diverse set of perspectives. We will discuss actual first contact protocols that seem to be in place today. We will then summarize first principles proposed so far – these are broad and basic, similar to the Hippocratic oath of “First do no harm”. We will also provide a diverse/cautionary perspective on first contact risks. We will wrap up the introductory talks with a reconnaissance of the rich exploration of first contact scenarios in science fiction. Then, an interactive session will enable attendees to express their ideas, insights, concerns, and hopes associated with first contact. Finally, this seminar/workshop has the potential to develop into a long-term working group to explore the topic in much greater detail and then synthesize the results into a coherent written report to be presented at the 7th TVIW Interstellar Symposium. Attendees will be asked if they wish to participate in such a long term effort. ”

Lead: Ken Wisian, Ph.D

Thanks for the plug, Al! The First Contact Working Group (FCWG–the name may change a bit as things develop) is still on-going. It’s development has been slowed quite a bit by the current virus panic, but it will be publicly unveiled sometime in the near future either under the auspices of TVIW or as a separate organization. When it is, we’ll be sure to let Paul know so he can either post about it here or can laugh and discard it. :)

Thanks Al and Doug

I strongly believe in Science Fiction as a powerful exploratory tool and this is a great example. I am teaching a course in the Fall – “Life in the Universe” and will look at incorporating Strangest of All.

Also, Doug, Ken Roy, John Traphagan and I are working to put on a physical/virtual conference on First Contact at UT Austin in the Fall. If we can get it together, you should see notice here in Centauri Dreams hopefully.

Hi Ken! We did a 2017 TVIW workshop together ending up with a SETI exhibition plan. Glad to be able to keep up with your thinking.

– Scott

Thank you so much for the link to Strangest of All. This blasted plague has closed the local library and I am dying for something good to read.

I look forward to a “good read”.

Happy to see the anthology covered here! I’ve been an avid reader (though very sparse commenter) of Centauri Dreams for years, so I’m excited about this. I hope the book makes readers who are new to astrobiology hungry for more, asking interesting questions and seeking resources such as your website.

And yes, we are definitely planning more :). In the most foreseeable future, we’ll see whether and how we can for instance collaborate with Europlanet on outreach activities for the first-ever virtual EPSC.

Great to have you here, Julie. And congratulations. You just did a splendid job on Strangest of All. Looking forward to what comes next.

Thanks for the anthology, Julie, and thanks CD for making it available to all!

I’m looking forward to some great short stories, after being sad I lost my copy of The Golden Age of Sci-Fi (can’t remember which volume), by Asimov.

This sounds intriguing. Recently I’ve been mulling over ideas for a life on Saturn story, except I’m not so good at things like characters, plot, pacing, and not writing something too boring for even me to read. But I don’t think my life forms are bad. They polymerize the impurities in Saturn’s atmosphere, most notably NH4SH and CH3, in a fibrous N-S-C based polymer (O, P, H, Ge, As are also available). I imagine them as a cell-free life form, as I imagine life on Earth arose, though you can argue insulating sheaths around fibers count as a “cell membrane” if you wish. Their energy source is the enstropy of the planet’s turbulent atmosphere – note the units of W/kg – which starts the fibers twisting rapidly and then stops them again, over and over. Harvesting this by piezoelectric effects, they use the energy for solid state flight. That, together with their thin membrane structure and tremendous tensile strength (I’ll allow them some graphene-like components to the fibers, I suppose) permits them to control their altitude long-term. I think it is much more plausible to evolve than the classic hot-hydrogen balloon. Germanium and germania (extracted from traces of germane in the air) provide a semiconducting matrix to harvest some sunlight, and form the lenses of their eyes. I imagine there are some interesting things that you could propose to do for biochemistry using focused coherent microwave bursts or transmission of phonons between adjacent strands of conductive polymer with protein-like functional groups? Not sure about that – any suggestions?

These organisms could make great platforms for symbionts that, improbably, found their way to Saturn from an ancient terrestrial impact, and more recently, for a certain crashed colony ship that had tried to aerobrake, dreaming of the caverns of Enceladus. (The initial shout of “Land Ho!” merited a skeptical reaction) With atmospheric pressure more than 10 bar, heliox – more hydrox! – breathing mixtures are appropriate, and available by supplementing the air with a bottle of oxygen, but the gravity is fine (1.07 g) and the temperature is OK with liquid water clouds. Some significant genetic reengineering to withstand caustic liquids and terrible odors (and motion sickness… all astronauts need that) would be highly advisable.

Alas, Uranus is tougher. You have to go to more like 100 bar to get decent watery temperatures in the atmosphere, but even so there is a lot more gas below it. Wikipedia says the base of the thermosphere is something like 1000 K, and you’re still not into the “icy ocean”. (Astronomer ice does not play well with mixed drinks) Neptune is anomalously hotter, if I remember correctly. Maybe after the Sun dies and some billions of years of cooling later there will be hope for fairly conventional life in those oceans.

Olaf Stapledon’s “Last and First Men” has the 18th (and last) men living on Neptune as the sun has made the inner system uninhabitable.

I should apologize for the hasty postscript in my comment above – the moral to take from it is if I’m being lazy enough to look up a figure in Wikipedia, I can be lazy enough to quote the *wrong* figure [the thermosphere is of course high above the cold layers of the atmosphere], plus failing to notice that the original story was by Geoffrey Landis, who knows a LOT more than I do about planets.

The blood-warm ocean model is certainly a departure from the “sea of liquid diamond” speculations you might see in some other places, but looking at https://arxiv.org/pdf/1909.04891.pdf it seems to hold up as plausible even in the face of much more recent data. See Figure 11 T(r) U-1 – in this model (though not in the others) pleasant temperatures appear to extend throughout the shallow depths explored in the story. What has been known since Voyager in 1987 is that there is very little heat flux coming away from Uranus – whether that is due to some sort of effective insulation around a very hot interior or because the original heat of the planet was somehow lost seems still to be open for debate.

I think my favorite “life on a gas giant” story will always be “A Meeting With Medusa”. Ever since I’ve loved the idea of long duration atmospheric probes for the gas giants. Not manned, of course, that would require nuclear propulsion to have a hope of leaving again.

But long duration. It seems a shame to spend years getting a probe to Jupiter or Saturn, and then lose it in the space of hours, when a simple hot hydrogen balloon kept warm by the isotope power supply powering the probe would allow a mission time of years.

Or an AI controlled atmospheric glider. There are clearly stable upwelling areas in Jupiter’s atmosphere where you could loiter at altitude for long periods of time with a glider, and have a lot of mobility.

“A Meeting with Medusa”! Great story.

I also recommend “The Medusa Chronicles” by Baxter and Reynolds. It is a good expansion of the core story with a lot more detail on the Jupiter life forms.

Yes, I thought that was a terrific read, and as you say, details well beyond the original.

I’m reading it now.

I hadn’t realize “A Meeting With Medusa” was set in an alternate history. Or is that something Baxter and Reynolds added?

I read Chronicles but was very dissapointed. Reynolds and Baxter do not make a good writing couple… I really don’t like Baxter’s novels very much.

Meeting, of course, is a great short story.

Thanks! Very interesting stories.

Julie,

Thanks for making this available and your commentary was very useful. Liked all the stories, yours is timely/relevant, and loved the one page thriller: SETI for Profit.

S

Thanks for the link to the new anthology!

I would like to ask about another book you discussed several years ago. I didn’t feel like I could afford it then, and I didn’t make a note of it. I searched your site for it.

The title was something like, Visions of Alien/Prehistoric/ Other Worlds.

The book displays illustrations, imagining how the skies and landscapes of Earth might have looked in prehistoric times, taking into account the motions and evolution of the stars over millions of years.

I hope somebody else remembers it. Thanks.

Vistas of Many Worlds, by Erik Anderson:

https://www.amazon.com/Vistas-Many-Worlds-Journey-Through/dp/0981986471/ref=sr_1_1?dchild=1&keywords=vistas+of+many+worlds&qid=1590444615&s=books&sr=1-1

Thank you for this great find. On my reading list after Stellaris-People of the Stars, which I am reading right now. Mr Benford and Nordley are excellent writers with thought provoking ideas and also quite open to discussing them with us lowly fans-as I had the pleasure to experience during WorldCon in London some years ago.

I recommend reading more on Peter Watts “Sunflowers” universe(“The Island” is part of this setting)-he uses his skills as scientists and writer to paint some interesting visions of interstellar exploration and necessary sacrifices humanity would have to make to change its outlook from planetary to galactic, and in the process changing its own nature.