One of my better memories involving space exploration is getting the chance to be at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory to see the Mars rovers Spirit and Opportunity just days before they were shipped off to Florida for their eventual launch. Being near an object that, though crafted by human hands, is about to be a presence on another world is an unusual experience, one that made me reflect on artifacts from deep in the human past and their excavation by archaeologists today. Will future humans one day recover our early robotic explorers?

That reflection was prompted by news from JPL that engineers have delivered the key elements of a critical ice-penetrating radar instrument for the European Space Agency’s mission to three of Jupiter’s icy moons. JUICE — JUpiter ICy moons Explorer — is scheduled for a launch in 2022, with plans to orbit Jupiter for three years, involving multiple flybys of both Europa and Callisto, with eventual orbital insertion at Ganymede. Analyses of the interiors as well as surfaces of the three moons should vastly improve our knowledge of their composition.

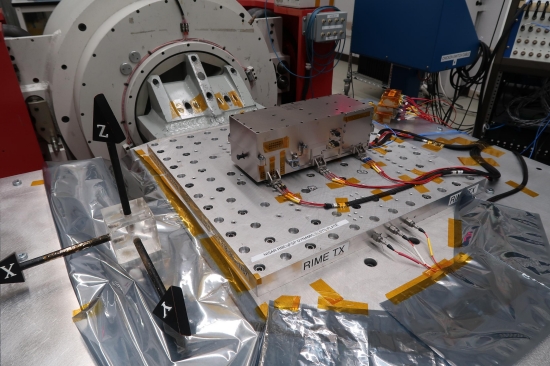

Image: NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory built and shipped the receiver, transmitter, and electronics necessary to complete the radar instrument for Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer (JUICE), the ESA (European Space Agency) mission to explore Jupiter and its three large icy moons. In this photo, shot at JPL on April 27, 2020, the transmitter undergoes random vibration testing to ensure the instrument can survive the shaking that comes with launch. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech.

Here again we’re looking at something in the hands of humans on Earth that will one day move out beyond our orbit, in this case to the moons of our system’s largest planet, sending back priceless data. On a practical level, this is what people in the space exploration business do. On the level of sheer human response, my own at least, looking at how we build our spacecraft puts a bit of a chill up my spine, the good kind of chill that signals being in the presence of something profound, something caught up in what seems a hard-wired human need to explore.

The words “ice-penetrating radar” should resonate among all of those who wonder about the ocean under the ice at Europa. But of course we also have reason to believe that both Ganymede and Callisto have oceans whose depths we have yet to measure. Getting a sense for how thick the ice is on these worlds will be part of what the JUICE mission’s RIME instrument will, we can hope, deliver. RIME — Radar for Icy Moon Exploration — is said to have the capability of sending out radio waves that can penetrate up to 10 kilometers deep, reflecting off subsurface features and helping us figure out the thickness of the ice.

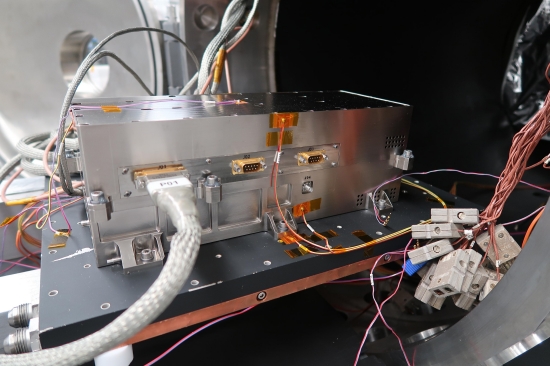

Image: The Radar for Icy Moon Exploration, or RIME, instrument is a collaboration by JPL and the Italian Space Agency (ASI) and is one of ten that will fly aboard JUICE. This photo, shot at JPL on July 23, 2020, shows the transmitter as it exits a thermal vacuum chamber. The test is one of several designed to ensure the hardware can survive the conditions of space travel. The thermal chamber simulates deep space by creating a vacuum and by varying the temperatures to match those the instrument will experience over the life of the mission. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech.

And as we all know, work on anything these days is complicated by COVID-19, with many JPL employees forced to work remotely, and necessary delays to equipment testing including vibration, shock and thermal vacuum tests to ensure the equipment is ready for the deep space environment. The engineers returning to work after the delay under new safety protocols faced a tight schedule, but they made it work. JPL delivered the transmitter and receiver for RIME along with electronics necessary for communicating with its antenna.

All this occurs as part of a collaboration between JPL and the Italian Space Agency (ASI). The RIME instrument is led by principal investigator Lorenzo Bruzzone (University of Trento, Italy). As to JPL’s role under trying pandemic conditions, co-principal investigator Jeffrey Plaut says:

“I’m really impressed that the engineers working on this project were able to pull this off. We are so proud of them, because it was incredibly challenging. We had a commitment to our partners overseas, and we met that – which is very gratifying.”

Gratifying indeed, and a reminder that along with JUICE, we can also anticipate NASA’s Europa Clipper, set to launch some time in the mid-2020s. Europa Clipper should arrive about the same time as JUICE, and will perform multiple flybys of Europa. Will we be able to determine the thickness of Europa’s frozen surface from the combined data of both missions? A relatively thin crust would make for the possibility of eventual penetration by instruments for a look at what lies beneath, but a shell of 15 to 25 kilometers in thickness would call for other strategies.

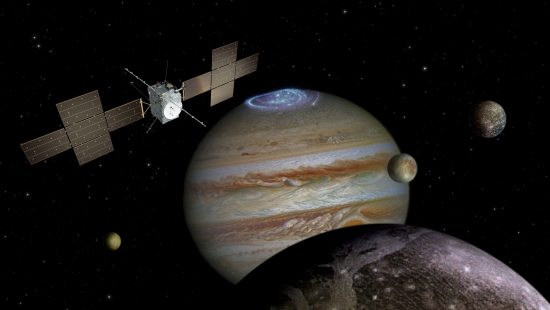

Image: The European Space Agency (ESA) Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer (JUICE) spacecraft explores the Jovian system in this illustration. Credit: ESA/NASA/ATG medialab/University of Leicester/DLR/JPL-Caltech/University of Arizona.

Ground penetrating radar from a distance and flyby. Awesome.

Thank you for a nice presentation, the RIME instrument page state 9 km penetration. While the text mention the generally assumed thickness of the ice of Europa 15-25 km. If this is correct the instrument might be able to see diapir formations (warm ice) and sites of geysers. But it will settle the question of the lenticulae have been caused by warmer ice or water. But for Ganymede and Callisto the ice sheet will be too thick, RIME might be useful in settling the question if the ice on Ganymede once have had continental drift. The idea have turned up from more than one researcher, and I guess in part of the surface appearance of this moon.

Will they be able to identify the motion of solid objects beneath the ice (dolphin-sized or tuna-sized)?

Yes, amazing to think of these hand crafted instruments operating in the awe inspiring Jovian system.

As has been already pointed out in the comments the nominal penetrating depth for RIME is 9km. This goal was set very early in the planning stages. In the mission statement there is speculation about possibly detecting the ice ocean interface which seems a little strange. Even 10 years ago the consensus was that Europa’s ice shell was much thicker than the 9km RIME penetrative capacity. While there is clear value in examining the structure of the subsurface ice, I can’t help but regret that the instrument’s capacity was not expanded to enable it to penetrate the more likely depth of the Europan ice shell even at the possible cost of lower spacial resolution.

I have this feeling that the cracks due to flexion actions will allow a liquid phase nearer the surface and maybe even less than 9km.

Just noticed JUICE’s RIME is Europa Clipper’s REASON. Somebody has a sense of humor.

Wonderful. Glad you caught this.

Might be a swipe at ESA for their unclear motivation to shoot for 9km with NASA showing more “reason”. But, that’s almost passive aggressive.

I suppose knowing the rock distribution in the ice would allow us to date the ice sheets better, i.e. more space rock less melting of the ice sheets as the rocks would fall out. I believe this rock debris would act as little oasis for life if they have got started on these moons by providing nutrients and protect from harsh radiation.

Interesting article on Europa,

https://www.lpi.usra.edu/publications/newsletters/lpib/new/radiation-maps-jupiters-moon-europa-key-future-missions/

https://www.nasa.gov/europa

Where to next in the outer solar system? Scientists have big ideas to explore icy moons and more.

By Meghan Bartels 20 hours ago

If you had a few billion dollars and some of the most talented space scientists and engineers in the world, where would you go?

There’s no wrong answer, really. Even if you narrow it down to just the outer solar system — planets, moons, rings and other cosmic rubble — you’ll never get bored. But that abundance of solar system destinations has downsides, of course, since there’s little chance of ever flying all the missions scientists can dream of. But dreaming up those missions anyway is a vital piece of space exploration, and one that scientists do regularly.

During a recent virtual meeting of the Outer Planets Assessment Group (OPAG), a science advisory group focused on everything past the asteroid belt, scientists walked the audience through three different mission concept studies that were commissioned to inform the Planetary Science Decadal Survey, which will guide NASA programs between 2023 and 2032.

https://www.space.com/outer-solar-system-flagship-mission-concepts

I found the write-up of RIME at https://meetingorganizer.copernicus.org/EPSC2013/EPSC2013-744-1.pdf – it sounds like they’re using 10 watts of power, a 16 meter antenna, and their stab at a best frequency (albeit one that will not let them image the side facing Jupiter due to noise). While I’d love to see them get deeper than 9 km, hopefully they should find *some* region where the internal ocean comes up toward the surface? The humans want to drill at one 0f those spots anyway.

I suppose the depth of penetration is dependent on power and frequency so perhaps they could use some orbital dynamics in the Jupiter system to change the range to tune into the best penetration depth.

Interesting idea of Jupiter’s magnetic field creating flows in the subsurface ocean and perhaps causing polar wonder.

https://phys.org/news/2019-03-jupiter-magnetic-field-europa-ocean.html

If we ever could put a coil around europa, it’s poles or even buried vertically it would create an enormous amount of power by induction. Perhaps a source of power for a drilling or laser driller machine.

It’s a pity they could not at least try a tether setup, jupiter’s field power is around 100 Terra Watts, even a fraction would amazing !

https://www.nextbigfuture.com/2014/11/jupiters-magnetic-field-can-provide.html