Milan M. ?irkovi?’s work has been frequently discussed on Centauri Dreams, as a glance in the archives will show. My own fascination with SETI and the implications of what has been called ‘the Fermi question’ led me early on to his papers, which explore the theoretical, cultural and philosophical space in which SETI proceeds. And there are few books in which I have put more annotations than his 2018 title The Great Silence: The Science and Philosophy of Fermi’s Paradox (Oxford University Press). Today Dr. ?irkovi? celebrates Stanislaw Lem, an author I first discovered way back in grad school and continue to admire today. A research professor at the Astronomical Observatory of Belgrade, (Serbia), ?irkovi? obtained his PhD at the Dept. of Physics, State University of New York in Stony Brook in 2000 with a thesis in astrophysical cosmology. He tells me his primary research interests are in the fields of astrobiology (habitable zones, habitability of galaxies, SETI studies), philosophy of science (futures studies, philosophy of cosmology), and risk analysis (global catastrophes, observation selection effects and the epistemology of risk). He co-edited the widely-cited anthology Global Catastrophic Risks (Oxford University Press, 2008) with Nick Bostrom, has published three research monographs and four popular science/general nonfiction books, and has authored about 200 research and professional papers.

by Milan ?irkovi?

This year we celebrate a centennial of the birth of a truly great author and thinker who is still, unfortunately, insufficiently well-known and read. Stanislaw Lem was born in 1921 in then Lwów, Poland (now Lviv, Ukraine). That was the year ?apek’s revolutionary drama R.U.R. premiered in Prague’s National Theatre and defined the word “robot”, Albert Einstein was awarded the Nobel Prize in physics for his work on the photoelectric effect in the course of which he effectively discovered photons, and one Adolf Hitler became the leader of a small far-right political party in Weimar Germany.

All three of these central-European developments have exerted a strong influence on Lem’s life and career. His studies of medicine, inspired by both his father’s distinguished medical career and his early-acquired mechanistic view of human beings, have been interrupted three times due to the chaos of WW2 and post-war changes. He narrowly escaped being executed by German authorities during the war for his resistance work. Finally, when he was on the verge of acquiring a diploma at the famous Jagiellonian University of Krakow, in 1949, he abandoned the pursuit in order to avoid the compulsory draft to which physicians were susceptible in the new communist Poland. He did some practical medical work in a maternity ward, but very quickly left medicine for good and became a full-time writer.

The apex of Lem’s creative career spans about three decades, from The Investigation published in 1958, to the publication of Fiasco and Peace on Earth in 1987. During that period, he published his greatest novels, in particular Solaris (1961), The Invincible (1966), His Master’s Voice (1968), and The Chain of Chance (1976), along with numerous short story anthologies, the most important being The Cyberiad (1965), as well as the Ijon Tichy and Pilot Pirx story cycles.

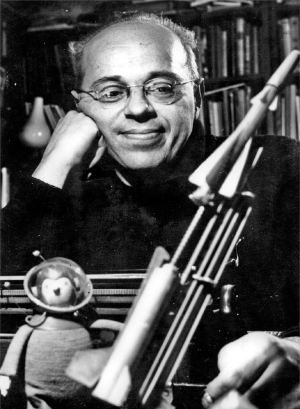

Image: Polish science fiction writer Stanislaw Lem. Credit: Wojciech Zemek.

Finally, several works in the Borgesian meta-genre of imaginary forewords, introductions, and book reviews, notably The Perfect Vacuum of 1971. This has been complemented by very extensive non-fiction writing, mainly in several fields of philosophy of science, futures studies, and literary criticism. The last two decades of Lem’s life were characterized by essayistic and publishing activity, as well as receiving innumerable prizes and awards, but no original fiction writing. Lem passed away peacefully on March 27, 2006, at the age of 84 in his home in Krakow.

Lem was obssessed by the theme of Contact: from his very first science-fiction novel, The Astronauts in 1951 (which he himself denounced as “childish”) to the last, great and deeply disturbing Fiasco, which is a kind of literary and philosophical testament. Nowhere, however, is his thought more in touch with the practical aspects of our SETI/search for technosignatures projects as in His Master’s Voice (originally published in 1968, that is only 8 years after the original Ozma Project! Translated into English by Michael Kandel only in 1983).

It is a brilliant work, perhaps the best novel ever written about SETI, but also a dense tract indeed. So, instead of many examples, I shall concentrate upon this one as a case study for the tremendous usefulness of reading Lem for anyone interested in astrobiology/SETI studies.

The study of the motives and ideas relevant for these fields would require a book-length treatment, as is obvious from the list of auxiliary topics Lem masterfully weaves into the narrative: from the ontological status of mathematical objects to the psyche of the Holocaust survivors, from preconditions for abiogenesis to the origin of the arrow of time. It is a challenging text in more than one sense; there is almost no dialogue and no manifest action beyond the recounting of a SETI project that not only failed but was never truly comprehended in the first place.

Image: A 1983 English edition of His Master’s Voice from Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, one of many editions available worldwide.

And this is a book whose plot should not be spoilt, since it is not as widely read as it should be half a century later. Without revealing too much, His Master’s Voice is set at a time when neutrino astrophysics is advanced enough to be able to detect possible modulations (imagined to have occurred near the end of the 20th century in the continued Cold War world). A neutrino signal repeating every 416 hours is discovered from a point in the sky within 1.5° of Alpha Canis Minoris. An eponymous top-secret project is then formed in order to decrypt the extraterrestrial signal, burdened by all the Cold-War paranoia and heavy-handed bureaucracy of the second half of the twentieth century. The project has its ups and downs, including some quite dramatic and literally threatening the survival of human civilization, but it is—obviously—mostly unsuccessful. The protagonist, a mathematical genius and cynic named Peter Hogarth, is neither a hero nor a villain; the SETI plot ends in anticlimactic uncertainty.

An intriguing consequence of Lem’s scenario is a realization that, while detectability generally increases with the progress of our astronomical detector technology, it does so very unevenly, in jumps or bursts. Although the powerful source of the “message” in the novel (presumably an alien beacon) had been present for a billion years or more, it became detectable only after a sophisticated neutrino-detecting hardware was developed. And even then, the detection of the signal happened serendipitously. Thus, in a rational approach to SETI—not often followed in practice, alas—the issue of detectability should be entirely decoupled from the issue of synchronization (the extent to which other intelligent species are contemporary to us).

Fermi’s paradox does not figure explicitly in His Master’s Voice (in contrast to many other of Lem’s works, especially his late and in my opinion equally magnificent Fiasco), and for an apparently obvious reason: “the starry letter” has always been here, or at least long enough on geological timescales. Detectability is, at least in part, a function of historical human development.

And there is a very real possibility, in the context of the plot, that “the letter” does not originate with intentional beings at all. The fulcrum of the book is reached when three radical hypotheses are presented to weary researchers, including the one attributing the signal to purely natural astrophysical processes! But even in this revisionist case, there are other problems, especially in light of the fact that the signal manifests “biophilic” properties: it helps complex biochemical reactions, and scientists in the novel speculate about whether it helped the abiogenesis on Earth. If it did so, the same necessarily occurred on many other planets in the Galaxy, so even if we abstract the mysterious Senders, it is natural to ask: where are our peers? This leads to more severe versions of Fermi’s paradox. In the same time, it makes us think about the various forms directed panspermia could, in fact, take when we reject our anthropocentric thinking.

There is another key lesson. While the discovery of even a single extraterrestrial artefact (and Lem’s neutrino message can surely be regarded as an artefact in the sense of the contemporary search for technosignatures), would be a great step forward, it would not, at least not immediately, resolve the problem. If one could conclude, as some of the protagonists of His Master’s Voice do, that there exist just two civilizations in the Galaxy, us and the mysterious Senders, that would still require explanation. Two is, in this particular context, sufficiently close if not equal to one.

And this shows, finally, the true gift of Lem’s thought to astrobiology and SETI studies: a capacity to go one step beyond in strangeness, to kick us sufficiently strongly out of the grooves of conventional thinking, to disturb us—and offend us, if necessary—and make us reject the comfortable and usual and mundane. In a general sense, all philosophy should do the same for us; that it usually does not is indeed discouraging and depressing. From time to time, however, a thinker passes with a bright torch illuminating the path and indicating how clueless we in fact are.

Lem was just such a figure. Reading him is indeed the highest form of celebration of reason and wisdom.

Spotted a few typos: the first name should be Stanis?aw. The Polish spelling of Lviv is Lwów not Lwov. The university in Kraków is known in English as the Jagiellonian University (Polish: Uniwersytet Jagiello?ski), not the Jagellonian University.

Thanks, andy. Will check with Milan on this and edit as necessary.

Stanislav Lem unknown? In USA perhaps, the rest of us consider him a grand master of SciFi. Reading the bestselling Solaris in my youth most likely triggered both my interest in space, life elsewhere as well as SETI and in the end the reason I make the post on this forum today.

He limited his serious writing to the alien encounters where he avoided bug eyed monster descriptions, and made them either incomprehensible (drifting coloured clouds in a crashed and dying biotech spacehip, nuclear powered spheres etc) or so grand that humans were mere insignificant ants like the child/juvenile superbeing ocean of Solaris. That each story never got a full explanation, only speculation, left the reader with a sense of wonder. So I have a hunch it also left me with a subconscious lesson that everything need not be explained or found the explanation for, which set me up for a career in blue sky research.

Besides he was a funny chap, who claimed that the moon lander lunar excursion module LEM was named after him. =)

I have read a number of Lem’s books (including HMV), but only the transplantations, some of which appear rather clunky. Has anyone here read the originals in Polish and compared them to the English translations? Does the humor translate well in the Tichy stories for example? Is the writing more subtle and interesting in the original Polish, or have the better translations captured it well?

The humour is more Polish language specific in some cases. The Fables for Robots especially. The more serious works are easier to translate ironically as they don’t use so much word play using language specific traits and sentences.

Solaris, the Russian version of the movie by Andrei Tarkovsky, is a masterpiece near to 2001 in its impact. IMHO

Thank you for the other novels which I’ve heard of but now must read!

I like to read Solaris as book, but do not like absolutely Andrei Tarkovsky movie.

While 2001 is a movie with very nice believable models of spacecraft, I prefer Andrej Arsenjevitj Tarkovskij for the discussions and implications made. The ending made me cry.

The Russian film industry also made a Hitchhiker guide to the galaxy type of film named Kin-dza-dza.

This one?

https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0091341

Looks like it is available on youtube with English subtitles.

Andrei, thank you for the Kin-dza-dza recommendation! I just watched it. Reminds me of the Fifth element x Mad Max x Monty Python

@Mr Tolley Yes you found it. @Scott Guerin: Glad you like it, yes the absurdities have similarities to Python also.

Andrei, I meant to add the comparison to an original Star Trek episode “Let that be your Last Battlefield” where the conflict people on Cheron, are black on their right sides, while Lokai’s people are all white on their right sides. As absurd as the pants distinctions!

That episode and Abraham Lincoln in space were examples of “jumping the shark” – a phrase used to characterize a television series that has run out of ideas and resorts to gimmicks to gain attention.

I enjoyed Star Trek in its first few years but found it annoyingly banal later on. The series Star Trek – the Next Generation brought new life, much better effects, thoughtful scripts and vastly better acting to the franchise.

Well, the original series only lasted three seasons, and declined in the third one (which included the Lincoln episode). My understanding is that many fans only regard the first two seasons as “canonical”.

I liked what I saw of Deep Space 9 but found Next Generation and especially Voyager to be authoritarian and smug (which of course reflects changes in the U.S. itself; it’s no longer the country I grew up in).

Yes, the Russian movie “Solaris” was a masterpiece on many levels. Roger Egbert, a highly regarded movie reviewer, agrees.

I saw his 1972 film “Solaris” at the Chicago Film Festival that year. It was my first experience of Tarkovsky, and at first I balked. It was long and slow and the dialogue seemed deliberately dry. But then the overall shape of the film floated into view, there were images of startling beauty, then developments that questioned the fundamental being of the characters themselves, and finally an ending that teasingly suggested that everything in the film needed to be seen in a new light. There was so much to think about afterwards, and so much that remained in my memory. With other Tarkovsky films–“Andrei Rublev,” “Nostalgia,” “The Sacrifice”–I had the same experience.

Thoughtful viewers will see the beauty in the movie so this movie is definitely not for everyone. It is a good thing that such movies put an engulfing and provocative message above commercialism. The movie 2001 is another example.

Star Wars and its numerous spinoffs are examples of deliberately made dumb movies aimed to maximize box office revenue and sales of relates toys. My grandchildren run around the house with their Star Wars customs going Peew Peew Peew with their lasers or whatever. Its a lot of fun but the movies are a wasteland of ideas.

By the way, Lem himself hated Tarkovsky’s movie version. He didn’t elaborate much, but it was obvious that Tarkovsky’s moral deliberations/lessons irritated him.

Lem strongly rejected the idea of universality of human morals and values in almost all his works. He even found the idea of us imposing our values on our own robots repulsive.

That is an interesting bit regarding Lem’s view on human morals. I wonder if an argument can be made for a universal morality for intelligent life based on fundamental characteristics of intelligence/awareness or ecological imperatives (way too speculative, I know).

Morality seems fundamentally driven by a desire for orderliness and stability so I would hope robots would be given a moral code such as proposed by Asimov

Here is the 1968 Soviet version of Solaris online with English subtitles:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=O1tnAyARsmA

Had it been better and more widely known back then, would this Solaris now be up there with 2001: A Space Odyssey, also released in 1968?

That movie is not the one under discussion which was released in 1972. I was not aware that there was an earlier version. Here are scenes from the 1972 version:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BBYJH6UAAfw

In any event, the 1972 version was not aimed at a mass audience. Both 2001 and Solaris were great movies but aimed at different markets.

Reading this post made me get out the only Lem novel in our collection, Memoirs of a Space Traveler. I think I will now try to read several of his other famous novels. Thank you for this beautifully written commentary on Stanislaw Lem and his life’s work Milan.

IIRC in “His Master’s Voice” Lem compares the human understanding of the alien signal to that of a caveman who finds a library, and thinks he’s discovered a really good source of fuel for his campfire. I’ll be surprised if we’re even able to make that much sense of something truly alien. Michio Kaku’s ant nest next to the freeway analogy is probably closer to our actual situation…

Back in the 1980s a number of Lem’s borderline short stories or essays appeared in the New Yorker magazine (in translation). Some of them were reviews of books never or not yet written. But one was a very interesting autobiography looking back into his possible antecedents.

Whether fictional or not, it posed questions that have stuck in my mind since: “Chance and Order.”

http://csc.ucdavis.edu/~chaos/courses/poci/Readings/Lem_CAO_NY1984.html

Having located this link, I am not sure if I am re-reading the original article or not. In this particular case, Lem speaks of his own origin in terms of his father’s near death by firing squad at the end of WWI and how chancy were the circumstances. But I distinctly recall in the account that I had read an examination of several generations of Lem predecessors, including an earlier chance meeting of a soldier in a field hospital and a nurse from divided parts of central Europe. Lem’s point was that both the meetings were highly unlikely – and likely that the ones before that were as well. The message being that individuals are often highly improbable products from the very start, powers of tens odds provided. Perhaps this elaboration was in another entry.

Other species here on Earth are not necessarily as individual as we are in their genetics or social heritages, but somehow, it is something Lem has given to ponder about life here on Earth or elsewhere.

I too, am of the opinion that alien intelligence will develop so differently from ours that communication with them (indeed, even recognizing them as intelligent) may be next to impossible. The constraint that we are a physics-oriented species will only allow us to locate other physics-oriented species. Analyzing electromagnetic radiation is our only current conceivable way of detecting alien activity, so only those civilizations which will generate powerful EMR as part of their communication or industrial activity will be detectable. Others who have favored other technologies (chemical, genetic, acoustic, bio- organic, linguistic, etc) may not leave any signals or traces for us, and will probably not be seeking anything we’re likely to routinely transmit into the void.

But even if they do build spaceships, radio telescopes and com lasers, will they still think and act like us, will they be organized socially the way we are, will they resemble us psychologically? Not only are intelligent ecosystems possible, but what about hive entities like social insects, parasitic, symbiotic or commensal species, or other, even more bizarre possibilities (have you considered space-faring slime molds or fungi?). Even “primitive” life on our own world has organized itself in some pretty interesting ways. Lem’s conceptions of sentient biospheres are important because they are an artist’s way of thinking abstractly about things we know nothing about,. something which artists are extremely good at. I’ve read no Lem myself, but a man of his artistic intuition and scientific training deserves to be listened to. He has a head start on the rest of us.

That doesn’t mean he’s necessarily going to get it right, it just means he’s less likely to get it all wrong.

What is successful in regards to an advanced civilization?

How about people that know their history.

And/or people that know their future.

Or some small percentage the people knowing their history and/or future.

It seems unlikely any advanced civilization will know their history or future.

But perhaps a successful advanced civilization will and can reach a point of having enough fun, yet.

Humans have never achieved this.

One might ask if humans had longer lifetimes, that this might go in this direction.

One could imagine even if humans had shorter lifetimes, that progress in that direction could occur. Or if some alien civilization had shorter lifetimes than human, they could be having a lot more fun, than humans are having.

It seems if we are not stuck on planet Earth, we could be having more fun.

I have long thought that if we have settlements on Mars, we would then have ocean settlements. Or if we “merely” had sub-orbital travel, we should also get ocean settlements resulting from it.

Or if we had Mars settlements, they going to do sub-orbital travel, they are also going to Space Power satellites- one could simply see it as not bringing solar panels, all the way to Mars surface, but bring them to Mars orbit. Mars orbit also good place mine space rocks and one going need electrical power to do this.

A long standing and common “argument” is living on the ocean could be cheaper than living on Mars. Also tiring “debate” of Moon vs Mars.

Which really was, which to do first.

Which could make more economical sense {to do first} L-5, Moon, Mars, ocean settlements, sub-orbital travel, SPS, or mining space rocks, and ect, ect.

It seems currently, we don’t know. What is needed roughly falls into the bin, that exploration is needed. Or simply someone has to try to do it. Or simply, when can it be done and/or discovered it doesn’t “work” now.

It has seemed, and seems, that we should first explore the Moon to determine if there is minable lunar water. But NASA should think of exploring the Moon as way to explore Mars. Or NASA should explore lunar polar regions to determine “ground truth” regarding possibility of mineable lunar water, but really get started on “same thing” in regards to Mars, as soon as possible, is there mineable Mars water, and where on Mars is it most mineable. And point is not that NASA is going to get into the mining business. One can say NASA is involved in airline business{it’s part of their charter} but that doesn’t mean NASA should run airlines. NASA should not mine anything and nor should colonize space, but NASA can’t even avoid not being involved in some ways with all of this. Or exploration is first part of doing this, and probably most exploration in space will not be done by NASA. If you living on Mars, or you are a Martian, then there good chance you will be involved all kinds of exploration of Mars and endless amounts of it will be done.

But it seems to me ocean settlements will be connected to Mars settlements, and it seems we start start making ocean settlements.

If any Earth bureaucrat wants to involved in colonizing anywhere, ocean settlements would be what they should focus on. And it can start, now, or should started decades ago.

In terms of ocean settlements, it seems the focus should related making suburbs to town/cities which are near and in the ocean. And effort could related to making breakwaters FOR coastal beaches.

A key aspect of any ocean settlement appears to related stopping wave with floating breakwater. Though rather than just stopping waves, one regard it also as making surfing areas to make good waves for surfing.

And simple words, one should make low income housing in the ocean where people at “living on the beach” and very close to a good place to surf. And do other fun things in the ocean.

Even on Earth we find examples of evolution in varying sociological paradigms. A slime mold is a bottom-up cooperative system with minimal division of labor and no hierarchy; some form separate cells, some don’t. Sponges have divisions of labor based on location of cells within the sponge, but the locations can change. In coelenterata the locations tend towards becoming fixed.

Among social insects such as ants and wasps there is a top-down hierarchy. Social vertebrates show hierarchical behavior and this is true of humans from the extant hunter-gatherer bands onwards.

Trees – and forests – form vast societies connected by underground fungal webs that transport nutrients and general information.

Alien life forms could have their historical origins in any of these kinds of organization, or more. Their motivations, values and behavior, language, culture and technology may be just as alien, eluding our understanding and even conceptualization.

An alien signal, even if characterizable as such, may be more undecipherable than some writings of lost human languages.

Thank you for articulating so succinctly some of the insights I was clumsily attempting to formulate in my post of 6/25/21. Recently, the SETI community has attempted to deal with these issues by proposing such concepts as Matrioshka brains, hive entities, distributed intelligences, machine civilizations and so on, but as followers of Stanislaw Lem have noted, writers have been successful at coming up with alternatives to the Bipedal Tool-using Naked Ape Straight Outta the Savanna paradigm.

What this means in practical terms to SETI researchers is that for alien civilizations interested in making contact with their neighbors, the traditional string of prime numbers broadcast in the Water Hole may still be the preferred beacon. But any real attempts at meaningful communication would probably be mutually unintelligible. In fact, I presume they would know this and never bother hailing us in the first place.

On the other hand, the possibility still exists that we may be able to eavesdrop on some of their other EM transmissions, either deliberate or accidental on their part, and if we can confidently determine they are artefacts rather than natural emissions we will finally know someone is out there.

What, or who, that someone is may still be as unknowable as ever.

My appreciation to Milan M. ?irkovi? for this fascinating post. IIRC, Lem stated that humans were not exploring space but merely taking the earth along with them. That was rather profound and can be applied to our limited potential to truly understand extraterrestrial intelligence. Actually we are clueless about our own intelligence/awareness (just my opinion).

Great post, thanks.

You mentioned Lem’s nonfiction and criticism work.

Here’s an essay Lem wrote about U.S. sf author P.K. Dick and some distinctions between popular scifi and the more literary and philosophical strain, among other things:

https://www.depauw.edu/sfs/backissues/5/lem5art.htm

I was not intending to read in its entirety upon seeing its length but, once started, it was hard to stop. I still have more to read but it comes across as brilliantly insightful and is causing a reassessment in my mind of what good Sci-Fi is.

Phillip K. Dick was a true visionary. His personal life was challenging but that can be expected when we see too much.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Philip_K._Dick

Ahem….Hitler became leader of the far LEFT National Socialist party. The work “National” leads to the convenient error.

Just no.

Nazi Party. The Nazis also used the slogan: “Arbeit macht frei” [“work sets you free”] at the entrance of the death camps. Very Orwellian.

The Two Cultures Revisited. Stanis?aw Lem’s His Master’s Voice

January 2020Interlitteraria 24(2):463-478

DOI:10.12697/IL.2019.24.2.15

Authors: Dominika Oramus

Abstract

I would like to take, as my starting point, the famous 1959 lecture of C. P. Snow, The Two Cultures, where science fiction is by and large ignored, and see how the consecutive points Snow is making are also discussed in the following decades of the 20th century by other philosophers of science, among them Stanis?aw Lem, Steven Weinberg, and Jonathan Gottschall.

In 1959 Snow postulated re-uniting the two cultures through the reform of education. In the 1960s and 1970s Lem did not believe in any reform, but prophesied that science left alone would procure the final war and, probably, the self-inflicted technological death of the West.

I am then going to juxtapose Snow’s argument with a science fiction novel concerned with the same civilizational crisis: Stanis law Lem’s His Master’s Voice.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/338613129_The_Two_Cultures_Revisited_Stanislaw_Lem's_His_Master's_Voice

A very interesting treatise. It seems clear that if science fiction was more respected as a genre it could provide the beginning of a bridge between the arts and the sciences. The current situation seems to prevent that from happening. People outside science don’t tend to read science fiction, any more than they tend to try to understand scientific concepts or discuss them. I know there are many people who associate fantasy with science fiction (I think that is a mistake) and therefore read a variety of literature that present fantasy as a genre (and may be of importance also) but it won’t bridge the gap between science and the arts I don’t think. The future may depend upon more people understanding scientific concepts and being able to reason carefully, and analytically. There is also a need for people to understand that dangers to humanity will not just disappear because they are unpleasant and therefore uncomfortable to think about realistically, and without attempts at denialism.

Thank you for this excellent article Milan and Centauri Dreams.

Suffice to say many Poles “grew up” on Lem’s works. Personally I started with Fables for Robots, which I would re-read a thousand times in my teenage years, and with that and his other works Lem became my gateway to all SF literature. Frankly it was difficult to find a matching level of cunningness, humour and insight in writing in the Western literature before I found Philip K. Dick (who was in conflict with Lem from what I know) and Douglas Adams.

In addition to SETI, Lem explored dozens of ideas which have not stopped fascinating us till today, including “brain in a vat” idea (popularized by the movie Matrix), meaning (or nonsense) of religion and the impossibility of pure faith, time travel, inability to communicate with alien beings, identity of robots (very similar concepts to Asimov), and many more. He also loved attaching very human qualities — greed, need for dominance, envy — to aliens, usually resulting in funny developments.

While Polish originals are very dear to my heart (Lem’s language is flamboyant, extravagant even, full of neologisms, and his inversions of word order are very slavic in nature), some of Lem’s English translations I’m aware of are rather brilliant I must say, trying to transpose Lem’s puns and plays on words. Have a look at this 5-minute read short story in English if you want a good sample of Lem’s humor: https://english.lem.pl/works/novels/the-cyberiad/146-how-the-world-was-saved

One last though on Lem – he had a thing for neutrinos. IIRC, the manifestations in Solaris were composed, at the subatomic scale, from stabilized collections of neutrinos. It’s handwavium but not bad handwavium.

Considering how prescient Lem was, he may have been on to something with neutrinos…

https://news.fnal.gov/tag/neutrino/

https://phys.org/tags/neutrinos/

This is when you know you have made the big time so far as general society is concerned…

https://www.thefirstnews.com/article/academic-creates-stanislaw-lem-lego-set-to-teach-youngsters-about-authors-works-23455

https://ideas.lego.com/projects/f88dac1b-321a-43b3-8e0f-f2c5fa368f68

Plus this video, the Visionary Sci-Fi World of Lem:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4TqLgD98Ioc

The details:

The First News

Often described as a prophet and visionary, world-renowned Sci-Fi writer and futurologist Stanis?aw Lem is the world’s most often translated Polish writer, whose book Solaris was perhaps his internationally best known work, twice made into a film, most recently directed by Steven Soderbergh with George Clooney in the starring role. His recognition is such that it was recently announced that European Space Agency astronauts travelling on Elon Musk’s SpaceX Crew Dragon spacecraft will honour Lem in space as part of their six-month mission.

With 2021 named in Poland as the year of Sci-Fi writer Stanis?aw Lem, who would have turned 100 this year, Heart of Poland’s Patrick Ney spoke to Szymon Kloska, curator of the Lem 2021 programme at the Kraków Festival Office about a fascinating man and the dozens of events being organised in his honour this year, including flagship project, Planet Lem.

“And yet we knew, for a certainty, that when first emissaries of Earth went walking among the planets, Earth’s other sons would be dreaming not about such expeditions but about a piece of bread.”

? Stanis?aw Lem, “His Master’s Voice”

Well said Jesus. People need basic human dignity and their basic needs fulfilled. Food, water, basic shelter, and health care. Just finished KSR’s Ministry of the Future. He speaks compellingly about these things. If I read it right he believes mankind’s hope of dealing with climate change will lie mainly with China, India, Europe, and an African federation of nations. You might notice what regions are startlingly absent. Russia is in many ways a rogue nation (like Canada as far as being a massive oil and gas producer and unwilling to move rapidly away from these wealth generating but extremely dangerous resources). He does say America will have a huge impact that will continue into the future but whether negative or positive (or both) is difficult to predict.

https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.3847/2515-5172/ac3428

Jules Verne’s Formulation of the Fermi Question

Graeme H. Smith1

Published November 2021 • © 2021. The Author(s). Published by the American Astronomical Society.

Research Notes of the AAS, Volume 5, Number 10

Citation Graeme H. Smith 2021 Res. Notes AAS 5 252

Abstract

Jules Verne’s novel Around the Moon envisions the circumlunar flight of a crewed projectile around the lunar farside ending with a safe return to Earth. The novel is justifiably famous, partly because of certain parallels it contains to the U.S. Apollo program a century later. What is less appreciated is that the novel contains a rather direct statement of what would later become known as the Fermi Question or Fermi Paradox.

Here are two articles on Lem from The New Yorker. The newest one details how his direct experiences with the Holocaust shaped his writing…

The Beautiful Mind-Bending of Stanislaw Lem

By Paul Grimstad

January 6, 2019

https://www.newyorker.com/culture/culture-desk/the-beautiful-mind-bending-of-stanislaw-lem

and…

January 17, 2022 Issue

A Holocaust Survivor’s Hardboiled Science Fiction

Though he rarely discussed them, Stanis?aw Lem’s experiences in wartime Poland weighed on him and affected his stories.

By Caleb Crain

January 10, 2022

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2022/01/17/a-holocaust-survivors-hardboiled-science-fiction

To quote:

In “His Master’s Voice,” a 1968 sci-fi novel by the Polish writer Stanis?aw Lem, a team of scientists and scholars convened by the American government try to decipher a neutrino signal from outer space. They manage to translate a fragment of the signal’s information, and a couple of the scientists use it to construct a powerful weapon, which the project’s senior mathematician fears could wipe out humanity. The intention behind the message remains elusive, but why would an advanced life-form have broadcast instructions that could be so dangerous?

Late one night, a philosopher on the team named Saul Rappaport, who emigrated from Europe in the last year of the Second World War, tells the mathematician about a time—“the year was 1942, I think”—when he nearly died in a mass execution. He was pulled off the street and put in a line of Jews waiting to be shot in a prison courtyard. Before his turn came, however, a German film crew arrived, and the killing was halted. Then a young Nazi officer asked for a volunteer to step forward. Rappaport couldn’t bring himself to, even though he sensed that, if no one did, everyone in line would be shot. Fortunately, another man volunteered; he was ordered to move cadavers but that was all. Why hadn’t the officer specified that the volunteer would not be harmed? Rappaport explains that this would never have occurred to the Nazi: “Although he spoke to us, you see, we were not people.” Maybe the senders of the neutrino message, Rappaport suggests, are similarly oblivious to human considerations. Maybe they can’t conceive of a life-form so rudimentary as to focus on the weaponizable part of the message. Rappaport’s interpretation turns out to be wrong, but his recollection, with its uncanny analogy between Nazis and aliens, feels like a key.

Lem, who died in 2006, would have celebrated his hundredth birthday this past fall, and M.I.T. Press has just republished six of his books and put out two in English for the first time. Lem is probably best known in the United States for his novel “Solaris” (1961)—the basis for sombre, eerie movies by Andrei Tarkovsky and Steven Soderbergh—about a distant planet where a sentient ocean confronts human visitors with a manifestation of a person whose memory they can’t get over. In former Warsaw Pact nations, his robot fables and astronaut tales sold in the millions. When he toured the Soviet Union in the nineteen-sixties, he was greeted by cosmonauts and astrophysicists, and addressed standing-room-only crowds. A self-described futurologist, he foresaw maps that could plot a route at a touch, immersive artificial realities, and instant, universal access to knowledge via “an enormous invisible web that encircles the world.”

A whole collection of Lem’s novels in English are free online here:

https://onlinereadfreenovel.com/stanislaw-lem/

Here is His Master’s Voice among the collection, which includes Solaris:

https://onlinereadfreenovel.com/stanislaw-lem/42040-his_masters_voice.html