The end of one year and the beginning of the next seems like a good time to back out to the big picture. The really big picture, where cosmology interacts with metaphysics. Thus today’s discussion of evolution and development in a cosmic context. John Smart wrote me after the recent death of Russian astronomer Alexander Zaitsev, having been with Sasha at the 2010 conference I discussed in my remembrance of Zaitsev. We also turned out to connect through the work of Clément Vidal, whose book The Beginning and the End tackles meaning from the cosmological perspective (see The Zen of SETI). As you’ll see, Smart and Vidal now work together on concepts described below, one of whose startling implications is that a tendency toward ethics and empathy may be a natural outgrowth of networked intelligence. Is our future invariably post-biological, and does such an outcome enhance or preclude journeys to the stars? John Smart is a global futurist, and a scholar of foresight process, science and technology, life sciences, and complex systems. His book Evolution, Development and Complexity: Multiscale Evolutionary Models of Complex Adaptive Systems (Springer) appeared in 2019. His latest title, Introduction to Foresight, 2021, is likewise available on Amazon.

by John Smart

In 2010, physicists Martin Dominik and John Zarnecki ran a Royal Society conference, Towards a Scientific and Societal Agenda on Extra-Terrestrial Life addressing scientific, legal, ethical, and political issues around the search for extra-terrestrial intelligence (SETI). Philosopher Clement Vidal and I both spoke at that conference. It was the first academic venue where I presented my Transcension Hypothesis, the idea that advanced intelligence everywhere may be developmentally-fated to venture into inner space, into increasingly local and miniaturized domains, with ever-greater density and interiority (simulation capacity, feelings, consciousness), rather than to expand into “outer space”, the more complex it becomes. When this process is taken to its physical limit, we get black-hole-like domains, which a few astrophysicists have speculated may allow us to “instantly” connect with all the other advanced civilizations which have entered a similar domain. Presumably each of these intelligent civilizations will then compare and contrast our locally unique, finite and incomplete science, experiences and wisdom, and if we are lucky, go on to make something even more complex and adaptive (a new network? a universe?) in the next cycle.

Clement and I co-founded our Evo-Devo Universe complexity research and discussion community in 2008 to explore the nature of our universe and its subsystems. Just as there are both evolutionary and developmental processes operating in living systems, with evolutionary processes being experimental, divergent, and unpredictable, and developmental processes being conservative, convergent, and predictable, we think that both evo and devo processes operate in our universe as well. If our universe is a replicating system, as several cosmologists believe, and if it exists in some larger environment, aka, the multiverse, it is plausible that both evolutionary and developmental processes would self-organize, under selection, to be of use to the universe as complex system. With respect to universal intelligence, it seems reasonable that both evolutionary diversity, with many unique local intelligences, and developmental convergence, with all such intelligences going through predictable hierarchical emergences and a life cycle, would emerge, just as both evolutionary and developmental processes regulate all living intelligences.

Once we grant that developmental processes exist, we can ask what kind of convergences might we predict for all advanced civilizations. One of those processes, accelerating change, seems particularly obvious, even though we still don’t have a science of that acceleration. (In 2003 I started a small nonprofit, ASF, to make that case). But what else might we expect? Does surviving universal intelligence become increasingly good, on average? Is there an “arc of progress” for the universe itself?

Developmental processes become increasingly regulated, predictable, and stable as function of their complexity and developmental history. Think of how much more predictable an adult organism is than a youth (try to predict your young kids thinking or behavior!), or how many less developmental failures occur in an adult versus a newly fertilized embryo. Development uses local chaos and contingency to converge predictably on a large set of far-future forms and functions, including youth, maturity, replication, senescence, and death, so the next generation may best continue the journey. At its core, life has never been about either individual or group success. Instead, life’s processes have self-organized, under selection, to advance network success. Well-built networks, not individuals or even groups, always progress. As a network, life is immortal, increasingly diverse and complex, and always improving its stability, resiliency, and intelligence.

But does universal intelligence also become increasingly good, on average, at the leading edge of network complexity? We humans are increasingly able to use our accelerating S&T to create evil, with ever-rising scale and intensity. But are we increasingly free to do so, or do we grow ever-more self-regulated and societally constrained? Steven Pinker, Rutger Bregman, and many others argue we have become increasingly self- and socially-constrained toward the good, for yet-unclear reasons, over our history. Read The Better Angels of Our Nature, 2012 and Humankind, 2021 for two influential books on that thesis. My own view on why we are increasingly constrained to be good is because there is a largely hidden but ever-growing network ethics and empathy holding human civilizations together. The subtlety, power, and value of our ethics and empathy grows incessantly in leading networks, apparently as a direct function of their complexity.

As a species, we are often unforesighted, coercive, and destructive. Individually, far too many of us are power-, possession- or wealth-oriented, zero-sum, cruel, selfish, and wasteful. Not seeing and valuing the big picture, we have created many new problems of progress, like climate change and environmental destruction, that we shamefully neglect. Yet we are also constantly progressing, always striving for positive visions of human empowerment, while imagining dystopias that we must prevent.

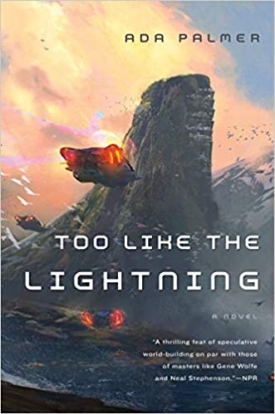

Ada Palmer’s science fiction debut, Too Like the Lightning, 2017 (I do not recommend the rest of the series), is a future world of technological abundance, accompanied by dehumanizing, centrally-planned control over what individuals can say, do, or believe. I don’t think Palmer has written a probable future. But it is plausible, under the wrong series of unfortunate and unforesighted future events, decisions and actions. Imagining such dystopias, and asking ourselves how to prevent them, is surely as important as positive visions to improving adaptiveness. I am also convinced we are rapidly and mostly unconsciously creating a civilization that will be ever more organized around our increasingly life-like machines. We can already see that these machines will be far smarter, faster, more capable, more miniaturized, more resource-independent, and more sustainable than our biology. That fast-approaching future will be importantly different from (and better than?) anything Earth’s amazing, nurturing environment has developed to date, and it is not well-represented in science-fiction yet, in my view.

On average, then, I strongly believe our human and technological networks grow increasingly good, the longer we survive, as some real function of their complexity. I also believe that postbiological life is an inevitable development, on all the presumably ubiquitous Earthlike planets in our universe. Not only does it seem likely that we will increasingly choose to merge with such life, it seems likely that it will be far smarter, stabler, more capable, more ethical, empathic, and more self-constrained than biological life could ever be, as an adaptive network. There is little science today to prove or disprove such beliefs. But they are worth stating and arguing.

Arguing the goodness of advanced intelligence was the subtext of the main debate at the SETI conference mentioned above. The highlight of this event was a panel debate on whether it is a good idea to not only listen for signs of extraterrrestrial intelligence (SETI), but to send messages (METI), broadcasting our existence, and hopefully, increase the chance that other advanced intelligences will communicate with us earlier, rather than later.

One of the most forceful proponents for such METI, Alexander Zaitsev, spoke at this conference. Clement and I had some good chats with him there (see picture below). Since 1999, Zaitsev has been using a radiotelescope in the Ukraine, RT-70, to broadcast “Hello” messages to nearby interesting stars. He did not ask permission, or consult with many others, before sending these messages. He simply acted on his belief that doing so would be a good act, and that those able to receive them would not only be more advanced, but would be inherently more good (ethical, empathic) than us.

Image: Alexander Zaitsev and John Smart, Royal Society SETI Conference, Chicheley Hall, UK, 2010. Credit: John Smart.

Sadly, Zaitsev has now passed away (see Paul Gilster’s beautiful elegy for him in these pages). It explains the 2010 conference, where Zaitsev debated others on the METI question, including David Brin. Brin advocates the most helpful position, one that asks for international and interdisciplinary debate prior to sending of messages. Such debate, and any guidelines it might lead to, can only help us with these important and long-neglected questions.

It was great listening to these titans debate at the conference, yet I also realized how far we are from a science that tells us the general Goodness of the Universe, to validate Zaitsev’s belief. We are a long way from his views being popular, or even discussed, today. Many scientists assume that we live in a randomness-dominated, “evolutionary” universe, when it seems much more likely that it is an evo-devo universe, with both many unpredictable and predictable things we can say about the nature of advanced complexity. Also, far too many of us still believe we are headed for the stars, when our history to date shows that the most complex networks are always headed inward, into zones of ever-greater locality, miniaturization, complexity, consciousness, ethics, empathy, and adaptiveness. As I say in my books, it seems that our destiny is density, and dematerialization. Perhaps all of this will even be proven in some future network science. We shall see.

I don’t think this has anything to do with development, but rather cultural norming. That is a very different thing. Human beings should all end up the same according to a developmental model, but in reality, which culture they develop in makes all the difference in beliefs, attitudes, and behavior.

You may be confusing this with survivorship bias. Any genetic defect will quickly eliminate the fetus, whist those without the defects will develop normally.

What do you mean by network here? What evidence is there to indicate this “network” has any bearing on evolution by the accepted current version of neo-Darwinism?

I am sure you must be aware of the criticisms of Pinker’s thesis on violence. Is the “violence” in western countries just more subtle? For example, is the cruelty of imposed inequality the new form of violence in our anglophone countries dominated by extreme shareholder vs stakeholder laissez-faire capitalism?

All that progressive thought might be lost if our collective inability to mitigate the climate crisis results in a degraded civilization, even an eventual collapse. Would the thesis only survive if the next civilization proves better than our current one? It took more than a millennium after the collapse of the Western Roman Empire for western civilization to reassert the equivalent greatness again. Rather a long timescale for that arc of progress to recover.

I agree with this, although I am not convinced humans will merge with our robotic intelligence rather than remain separated, and that the robots will become the dominant space-faring “species”. Whether they will have advanced intellectually as you suggest, or just extend the “paperclip maximizers” of our corporate beings is uncertain.

Unless there are other civilizations overlapping with ours and close enough to communicate with beyond just a 1-way signal, METI will be as useless as all that prayer for divine guidance and intervention that so many religions promulgate. Religion might have cultural advantages to hold societies together, but there is zero evidence any benefit comes from the gods it abases itself to. METI is probably just shouting into the void, and arguably just a technology-based religion hoping for some sort of communion and possibly salvation. Wouldn’t it be interesting if by some surprise we get a message back, saying in effect, “Don’t bother to call again. You are on your own. You must solve your problems yourselves. If you don’t survive, we may note your passing in the Encyclopedia Galactica.”

In this alternative future, the HHGTTU’s Ford Prefect might again amend the Hitchhikers Guide entry for Earth from “Mostly harmless”, to “Mostly stupid. Now dead”.

“For example, is the cruelty of imposed inequality the new form of violence in our anglophone countries dominated by extreme shareholder vs stakeholder laissez-faire capitalism?”

Huh??? If something characterises recent decades in the anglophone and in general western countries (the Americas and Europe) is a sustained increase in regulation and dictatorship, which has exploded in the pandemic years.

Anglophone countries are UK, US, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand. Europe is not Anglophone. It is the these countries that have run with the maximizing shareholder return approach to running corporations which has also resulted in tax reductions and tax manipulation by these entities, control of the legislatures (using these excess returns), and the undeniable increase in inequality, incarceration rates (especially the US), poor treatment of outgroups in society (especially Australia) and a general hardening of attitudes by victim blaming the poorest.

One wonders if there are any other civilizations out there, whether this is the convergence they aspire to.

Alex, your analysis here is spot on. Right-wing “Libertarianism” aka authoritarianism-in-practice aka closet authoritarianism leading to Oligarchy has been the dominant strain in the Anglophone countries during the last 40 years. Your point about progress being negated if ways to balance the individual, the collective, and the environment are not improved on upon in short order. The ship has sailed for incremental tweaks of the system.

Hello Alex!

I have long enjoyed the rigor and clarity of your posts on this site, and it is a pleasure to get this kind of detailed and thoughtful feedback. Let me respond in line to your points (A: and J: are you and I, I don’t know if this cut and paste will preserve indents).

J: Developmental processes become increasingly regulated, predictable, and stable as function of their complexity and developmental history. Think of how much more predictable an adult organism is than a youth (try to predict your young kids thinking or behavior!)

A: I don’t think this has anything to do with development, but rather cultural norming. That is a very different thing. Human beings should all end up the same according to a developmental model, but in reality, which culture they develop in makes all the difference in beliefs, attitudes, and behavior.

J: Actually, it does. The further along in the life cycle any organism gets, the more it has a set of highly predictable behaviors. Culture of course influences these developmental features, but that is evolutionary variety (of beliefs, norms, ideas) overlaid on the developmental plan. Any developmental psychologist will cite many predictable features of all adults. Youth are the most unpredictable, in all cultures, on many axes. Elders the most predictable. Even elders with no children and few social ties, and thus little to culturally inhibit them, do not “re-radicalize” their behaviors as they did in youth. Instead, they have self-constrained, into routines whose future you can predict greatly from just a few days of study. Can’t do that with kids.

J: how many less developmental failures occur in an adult versus a newly fertilized embryo.

A: You may be confusing this with survivorship bias. Any genetic defect will quickly eliminate the fetus, whist those without the defects will develop normally.

J: I’m describing a survivor curve, and it the opposite of survivorship bias. Survivorship bias would exist if we assume that just because adults are more developmentally stable, development has always been stable. What happens is actually the opposite. Survival is very questionable for an embryo, early in its developmental unfolding. There is less tolerance for errors of a certain type, including certain obviously checkable genetic defects as you describe. But many defects don’t threaten development, only adaptability of the organism. Besides a growing tolerance for errors, as complex regulatory processes and circuits mature, they themselves stabilize the organism in ways not possible in the less developed organism. It is not clear to me which of these two factors is more important to stability. My intuition is that it is the developed complexity of the mature organism that is the dominant factor in its growing stability. The mature networks stabilize the adult organism further (and in an elderly organism, overstabilize it, setting it up for brittleness and eventual failure and recycling).

J: At its core, life has never been about either individual or group success. Instead, life’s processes have self-organized, under selection, to advance network success. Well-built networks, not individuals or even groups, always progress.

A: What do you mean by network here? What evidence is there to indicate this “network” has any bearing on evolution by the accepted current version of neo-Darwinism?

J: This is a great question that may be difficult to answer well today. But I can offer some starter answers. One way to define what I mean by network is to look at life itself. It has so many levels and scales of structure and function, yet it is a network, with vast connections between it. Constant communication, feedback, and dynamic balancing exists across it, at so many scales. Estimates are that fully 10% of even our genome is viral in origin. All of life acts like bacteria, which with their horizontal gene transfer can be considered both a single network and a collection of groups (species). What I’m describing here is that we need what the theoretical biologists call an Extended Evolutionary Synthesis. Standard neo-Darwinism is so narrow a view of what is actually happening that it is dangerous to assume that it is the dominant set of drivers for macrobiological complexity. I wrote a post last year about molecular convergent evolution that speaks to both of these points (centrality of networks and the limits of Darwinian models). (https://eversmarterworld.com/2020/01/22/the-tangled-tree-isnt-so-tangled-telling-the-story-of-molecular-convergent-evolution/)

A: I am sure you must be aware of the criticisms of Pinker’s thesis on violence. Is the “violence” in western countries just more subtle? For example, is the cruelty of imposed inequality the new form of violence in our anglophone countries dominated by extreme shareholder vs stakeholder laissez-faire capitalism?

J: Yes, Pinker took on a mammoth and thankless task, trying to show the curve of goodness in human history. He was by no means the first. Many others have seen this “arc of self-constraint” and have commented on it or attempted to document it. Norbert Elias did a great job in The Civilizing Process, 1939, covering Europe’s arc of chaotic improvement in ethics and empathy from 800-1900 CE. Rutger Bregman’s Humankind, 2019, is a great update to Pinker’s work. It deftly describes Pinker’s work, deals with his many ideologically motivated critics, and shows the mistakes he made in not describing how much less violent conditions were in the period before the age of empires. So the arc has more humps than Pinker portrayed, but discerning folks knew that anyway. Bregman endorses Pinker’s thesis and then goes well beyond it. I think you in particular may enjoy the book as he exposes many false assumptions in 20th century popular anthropology in the process.

J: Not seeing and valuing the big picture, we have created many new problems of progress, like climate change and environmental destruction, that we shamefully neglect. Yet we are also constantly progressing, always striving for positive visions of human empowerment, while imagining dystopias that we must prevent.

A: All that progressive thought might be lost if our collective inability to mitigate the climate crisis results in a degraded civilization, even an eventual collapse. Would the thesis only survive if the next civilization proves better than our current one? It took more than a millennium after the collapse of the Western Roman Empire for western civilization to reassert the equivalent greatness again. Rather a long timescale for that arc of progress to recover.

J: Yes, climate change is important, and we must greatly decarbonize our food, energy, manufacturing, and lifestyle, but are we not doing so exponentially on an annual basis now? Population is collapsing globally. Everyone with electronics is choosing increasingly dematerialized lifestyles and sustainability ethics. (See Andrew McAfee’s More From Less, 2019 for a great recent account). Are you not yourself slipping into political fashionability to intimate our climate crisis as something that might lead to civilizational “collapse?” Climate change is surely a major problem of human adaptation, yes. But of human survival? I think not. The best brief piece on climate change I’ve ever read is Matt Ridley’s Why Climate Change is Good for the World, in the UK’s The Spectator, 2013. (https://www.spectator.co.uk/article/why-climate-change-is-good-for-the-world). I like to go back and reread that at least once a year, to give me perspective. That is the true assessment that will never be front page news, in my view. It would be reckless to shirk our responsibility to change, assuming it will occur without us, but it is the accurate assessment when we do change. At the same time we need ever heightening panic stories to get ourselves to change. That’s just a political and psychological reality. But those stories never describe the most probable future—that we always adapt.

Your point on the Roman Empire is one I originally believed as well, until I looked closer at the “fall”, and started to see that it was not much of a fall for the network, or even for civilization, but rather, for the particular set of organizations and priorities that was Rome. It is hard to briefly defend this view, but let me try anyway. In evo-devo models, there is a constant tension between bottom-up, exploratory, unpredictable evolutionary change, and top-down, convergent, conservative, developmental change. That tension is evident in phases where one or the other (evolutionary or developmental processes) dominates network complexification, for a time and context, before giving way to the other again. The incredible organizational and technical progress we made during the Roman Empire was one of those dominant developmental phases, in my book. Not for science (we can thank the Greeks for that, and the East after Rome’s fall), but for technical and organizational advances. Many parallels there to how China is advancing today. That empire (but not the network!) eventually became overdeveloped, brittle, senescent, and had to fail and reorganize. It was replaced with another top-down empire, based on Christian monotheism, that devalued many Roman advances (engineering, cities, commerce, warfare, etc), kept others (authoritarianism and Rome’s late conversion to Christianity) and tried to just as ruthlessly prevent bottom-up, creative, individualized progress and experimentation. Nevertheless, as Medieval scholars like Anne RJ Turgot and Lesley White have shown, technological and organizational progress continued throughout the Dark Ages, and remained on a slow exponential (ran increasingly fast) over time. It was now far more local and practical in scale. Benedictine monks were a network spreading “the useful arts” (technology practices). Water wheel networks sprouted across Europe, driving productivity and commerce. Eventually we got the Renaissance, and a shift to a bottom up (evolutionary) phase of progress, and our first democracies. In this network-centric view I’ve sketched, network complexity and acceleration, and the cumulative knowledge within the network, is very, very hard to stop, or slow down. It is redundantly stored (one basic feature of adaptive networks), and the centers will often shift location after local catastrophes. Scientific advances and knowledge shifted to the Middle East after Rome fell, for example. The network, in this story, is always accelerating, at its leading edge, and it is almost always progressing somewhere. Sorry for the long-winded response.

J: I also believe that postbiological life is an inevitable development, on all the presumably ubiquitous Earthlike planets in our universe.

A: I agree with this, although I am not convinced humans will merge with our robotic intelligence rather than remain separated, and that the robots will become the dominant space-faring “species”. Whether they will have advanced intellectually as you suggest, or just extend the “paperclip maximizers” of our corporate beings is uncertain.

J: Wonderful! I did not expect your agreement on the postbiological life development on Earthlikes topic. I am very curious as to how you personally come to this conclusion. I came to this conclusion via the phenomenon of accelerating change. Carl Sagan’s Cosmic Calendar made a deep impression on me as a youth. You don’t see any long periods of stasis in that calendar. Even in the places where you might expect them, such as Earth’s many extinction events, when you look closer, you can see network acceleration everywhere, as with the Dark Ages. Earth’s major extinction events, for example, seem to have done little to reduce the diversity of the genetic network. Yes, most species were lost, but very little (amazingly little!) of our *genetic diversity* (especially of the conserved core of developmental genes), and its intrinsic evolutionary molecular, functional and morphological diversity. That was the *network that mattered most,* in keeping the biological morphofunctional acceleration going. In fact, immediately after each extinction, the record shows a new acceleration of evolutionary diversity in the surviving forms. So the catastrophes themselves are *catalytic* to network complexity. I think that is one defining feature of well-built networks. Not only are they redundant and fault-tolerant, they are antifragile. They get stronger and more innovative under stress. That will have to be a central feature of leading postbiological life, in my view. As for the postbiological issue, even as our current primitive neuroscience and AI advance, we’re learning to put ever more critical features of our own biological and neural networks into our bio-inspired machines. There are research programs to make them both more evolutionary and developmental, in both hardware and software. Deep learning AIs are today trained, no longer coded. No one understand their algorithms. They are associative, like human neural algorithms. And they can think, and simulate, at electronic rather than electrochemical speeds. That is at least a *seven-million-fold faster rate of learning*. I think General AI is still many decades away, but with this learning differential (and once they are self-improving, a similar evolutionary and simulation differential) I don’t see how biology remains influential for much longer, from a cosmic perspective. Many others have written on this for a century now, so I won’t belabor the point. But I do have a few posts on the future of human and machine mind and their merger that might be of interest.

Your Personal AI (Five Part Series), Medium, 2016 https://johnsmart.medium.com/your-personal-sim-a07d78ffdd40#.jhfytmbf9

Contemplating Mortality: Personal AIs, Mind Melds, and Other Paths to Our Postbiological Future, Medium, 2020

https://johnsmart.medium.com/contemplating-mortality-personal-ais-mind-melds-and-other-inevitable-paths-to-our-b37f091191c9

If you don’t mind Alex, I would love to ask you a few questions, to better understand the worldview and assumptions you use to understand complexity and change: What does the phrase “universal development” mean to you? What kinds of universal processes do you think are a candidate for being not simply an evolutionary (random, contingent, unpredictable) process, but a developmental (convergent, conservative, predictable) process? Do you see the mathematical case for at least some universal fine tuning? Do you find value in cosmology models that treat the universe as a replicating system, embedded in a multiverse, and possibly being under some sort of selection? Can you see the case that all interesting things in the universe (except galaxies and large scale structure which we can assume replicate as dependent elements of their parent universe) appear to be replicative, evolutionary and developmental? Suns, for example are clearly all of these three things, by the above definitions. Finally, would you agree with me that the process of *biological development* how it actually works and can be so consistent, as we see in two genetically “identical” twins even when separated at birth and raised in very different environments, is both the most amazing, and one of the most incompletely mathematically modeled, processes in our known universe? I’m not trying to be argumentative, I am just curious. It is very helpful for me to understand different worldviews.

Finally, on the subject of worldviews (cosmos views?) I would like to make one small observation about how our views may differ at present, at least as I see it today. It seems to me that some of your CD posts display a preference toward, or an assumption about, a “randomness-centric” view of complex systems change. For example, your exoplanet post of May 2021 https://centauri-dreams.org/2021/05/28/are-planets-with-continuous-surface-habitability-rare/ analyzed a paper by Tyrell in which “It is assumed that there is no inherent bias in the climate systems of planets as a whole towards either negative (stabilising) or positive (destabilising) feedbacks.” This is to me a poor assumption to make about such an important feature (feedback) in any complex system. I would argue that it leads to a math that is so one-sided and simplistic that its conclusions cannot be trusted. You have a great facility with math and rigor, and I am very impressed with it, but I do think it is easy for us to get our assumptions wrong when we set up our analysis. I’m sure you know that there are many geochemists, planetologists, astrobiologists, physicists, ecologists, and biologists who find value in some variation of the geo-chemo-bio-climate homeostatic Gaia Hypothesis. Not as aggressively as Lovelock stated it, but in some milder and much more qualified form. Earthlikes do appear to be very very good nurseries for life. Life sprang up on our Earth almost immediately as the crust was cooling. Earthlikes may be both a great nursery and a great “finishing school”, for taking life to the postbiological state, in an accelerating, network-centric process. Many of these climate stabilizing Gaia processes are prebiotic. Plate tectonics strongly stabilizes atomospheric CO2 buildup on Earthlikes, for example, even without ocean plankton. To make an assumption of feedback randomness in climate systems takes a piece of the whole complex puzzle and simplifies it dangerously, as I see it at least. Perhaps I am misunderstanding your analysis and the paper. To me, that kind of assumption makes sense if we live in a randomness-dominated universe. But if we live in an *evo-devo universe* where both random and predictable physics operate at all scales, in all hierarchies of complexity, and throughout the life cycle of the complex system (organism, star, planet) then we will need math of both types to describe such critical system properties. And if not just evolution but evolutionary development is occurring on our most complex planets we will need math that describes how the critical networks on those planets are increasingly stabilizing and antifragile (and in my view, ethical and empathic) as a function of their complexity, just as biological network development appears to be. Without that kind of math, I don’t think we can’t expect to rigorously address the big questions. I expect that math will come from biology and complex networks in coming decades, and we’ll eventually learn to apply it on cosmic scales.

This is all quite speculative of course, but I find great value in making our limited arguments today, as best we can. Thanks again for all you do for the CD community. Warmest regards, John

Hi John,

Thank you for what I think is the most thoughtful reply to my comments on CD to date.

1. development of networks and stability. Let’s just the brain as an example. The lower predictability of the pre-adult brain (those unruly teenagers) is due to the greater connections between neurons and chaotic firing. With aging, connections get reduced, reducing network complexity, in favor of predictability. I would argue that network complexity is reduced with age, not increased. A counterargument might be that effective network complexity is improved with age, at the cost of plasticity (old dogs, new tricks, etc.). What about bodily homeostasis? Anyone who has aged knows that homeostasis starts to fail with age, e.g. inability to stay warm in winter.

2. survivorship curve vs survivor bias. I am reminded of Freeman Dyson’s wartime experience when his team had to determine where the armor on the aircraft had to be reinforced. It wasn’t where the cannon holes were, but rather where they were not. Fetal development rapidly goes wrong at an early stage due to genetic and other defects. Miscarriages, early post-natal death, etc. Once those individuals have been removed, those that remain, the survivors are relatively free of defects. I apologize if I have the terms mixed up, but as far as I can tell, what we are seeing in adults is survivorship bias. It is why one does not pay attention to CEOs who succeed, or oldsters explaining why they have lived a long life. The reality is that they have just had the good fortune to be free of the problems (and random accidents) of their peers. Survivorship Bias.

3. I read your piece about the tangled world. I don’t think anyone doubts that the constraints of physics drive organisms to try to climb the same fitness hill using the assets they already have. We certainly see the classic morphological convergence between sharks, dolphins, and ichthyosaurs. Your example of the antifreeze proteins is similar. But what are the constraints for the non-physical world, e.g. abstract thought? As I said, McCarthy thought that this would cause convergence in intelligence as the universe seems to have common laws of physics, logic, and math. But we really cannot be sure that this will drive intelligence to converge, other than perhaps its subsystems that deal with these constraints. The average human spends more time thinking about other things, such as social interactions, which are surely not constrained. For example, the traits that drive sex selection appear entirely arbitrary, once one abandons the Kiplinesque “just so” explanations of the features.

Yes, I agree, that the web of life is likely more tangled than we thought. Lynn Margulis was one proponent of horizontal gene transfer between higher animals, and there may be some elements of this in different invertebrate life stages too. Retro-viruses do insert themselves into genomes, but AFAIK, most cause damage, such as cancer. Some will confer benefits when modified and given a promoter sequence to express them. Do we have any idea of how frequent retro-virus insertions are and how many confer advantages, rather than disadvantages?

lastly, the increasing complexity of ecological webs does confer robustness – usually. But bear in mind that it is highly dependent on network structure. Small-world networks often have single points of failure. In the animal world, the removal of just one species, such as a top predator can degrade the whole ecosystem that depended on a key function of that organism. One we are facing right now is the loss of honey bee pollinators. They are just one type of pollinator, but by far the most important. If honey bees disappeared tomorrow, an awful amount of plant diversity and our foods would disappear too.

4. I would really try to avoid Matt Ridley. I consider him as unreliable as Bjørn Lomborg (the Skeptical Environmentalist).

RegardingAncient Rome, I like the economic analysis of Paul Kennedy’s “The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers”. I would argue that the failure to be able to maintain the frontier represents a diminution of the network as peripheral networks gain relative power. Conditions in England certainly got worse for many after Rome abandoned the island. It was also the beginning of the dark ages. Travel became more unreliable. Trade was more difficult. I see all this as a breaking of established networks, not increasing them.

If the Pax Americana ends, and there is no replacement by a Pax Sinica, do you really believe that networks are getting more complex? The recent problems with supply chains show how brittle those “complex networks” are. And when broken, network effects can cause cascade failures.

Why do I think that we will be followed by postbiological “life”? Let me clarify and say that robots and artificial intelligence will be the dominant “life” in space. I have used this analogy many times: We are like Devonian fish wanting to colonize the dry land and needing to build aquaria to do so. It was evolution organisms, in the vertebrate case, of retiles that achieved this goal. Robots are pre-adapted to space, able to survive in many environments, effectively naked. They can slumber through long journeys and therefore achieve interstellar travel. Biological humans might follow in some cases, building supportive habitats and ingenious ways to travel vast distances, but robots have a clear advantage. On Earth, I see humans as remaining biological, albeit speciating with genetic engineering and becoming increasingly cyborg in some cases. But there will be immense variety, from humans 1.0, to all manner of species and biology-machine hybrids.

In the space of a mere century, we have seen robots develop from concept (Capek’s RUR), Asimov’s robots, to crude metal demos, to semi-intelligent humanoid robots, software AIs, and robotic probes. This pace will continue. Unless there is some limit that artificial computation comes up against to prevent AGI, then I see this as inevitable.

So a mix of fable and reality, some knowledge of symbolic and neural AI, and the likely merging of the 2. Because we can already assemble, disassemble and rebuild robots, transfer their brains electronically, robotic minds can spread across the galaxy at the speed of light as long as there is an assembler to recreate the physical form at the other end.

Re: Universal development. This is the first I have heard of the term. I have no thoughts on it at the moment.

Re: processes that are developmental. As I don’t know that I even agree with your viewpoint, this is difficult. I do think about attractors – whether purely mathematical, or embodied in life. Stuart Kauffman’s book “The Origin of Order” is full of attractors, computationally modeled, but reflecting what he sees in biology. It is that very problem that I am currently trying to deal with computationally to arrive at ways biology can display complex innate behaviors without learning. Given how stochastic so much neural growth seems to display, I am at a loss to understand how that development leads to innate behavior, such as requiring responses to intricate sensory input like mating dances in insects. As regards the fine-tuning of our universe, that could just be chance and the fact that we inhabit the only one that works. Without knowing the details of the creation of universes, I have no idea what factors could be involved in the natural selection of certain types of universe. I don’t accept the idea of a creator, but if there was proof that one exists[ed] then I would change my mind.

Re: The post on Tyrell’s paper. He and I had discussions about the model. I understood what he was trying to achieve, but personally, I think the real feedbacks are more stabilizing than he suggested. I ran a number of experiments altering his model parameters to understand it better and I know he is looking to try to incorporate more realistic models for planetary climates than his simple Matlab model used.

Having said that, randomness is a very powerful tool in computation. It solves a lot of problems in goal-seeking and optimization that breaks purely deterministic models. It should always be used as a null hypothesis to test against. I have David Raup’s book “Extinction” in which he shows that random models explain extinctions without resorting to external events, or even genetics. IOW, the idea that the 5 great extinctions are caused by cosmic or geologic events is coincidental. I don’t think that is true, but if randomness explains the extinctions, it is important to show why the extinctions are truly caused, not just coincidental, by external events.

I do agree with you that mathematical modeling is going to help find the answers to some big questions. I am always interested in models that appear to show how events happen, such as planetary formation, but at the same time, I am aware that bias can creep in to include “magic numbers” and the use of some functions that will result in the outcomes wanted. Science is a self-correcting process that will eventually find the truth, especially when anchored to data.

Hi Alex,

Fantastic response, thank you. Let me make brief reply (work starts again tomorrow).

1. Yes, I can see many ways network complexity reduces with age. I was referring to regulatory stability, a different concept. That goes up as those connections prune away. Half the brain cells disappear in the first five years, roughly. It’s a massive pruning, and a stabilization as well. That stabilization is a real hallmark of development (and overstabilization and brittleness in advanced age). We can find it this curve in people, ecosystems, organizations, cultures, and I’d argue, for all of biological life, prior to getting its developmental code rejuvenated.

2. We may be talking past each other here. Demographers have a concept, the survival curve, that describes the odds of continuing to survive from where you are at present. Your odds go up steadily until you hit maturity. That’s the stabilization I’m talking about that happens with normal development. You may misperceive the danger of the past (survivorship bias) or accurately know the past survival curve, but that’s a perception topic. I’m just talking about the a known feature of biological development, one that may operate if the universe is also developing. Developmental genetics, and metastable environmental boundary conditions presumably guide that process. The subset of universal parameters that appear to be finely tuned, and metastable multiversal boundary conditions, could simultaneously guide the same curiously smooth acceleration we see on Earth, and presumably, other Earthlikes. In other words, the core features intelligence, ethics, and empathy that all complex living networks may have to develop, along with our universe’s special physics that allows continual miniaturization digitization, and network redundancy, may be core to that stabilizing process (the “chaotic arc of progress” we are musing about.).

3. re: sex and cultural behaviors being “unconstrained.” I wonder if this analogy helps. Developmental processes always create an “envelope” to constrain evolutionary stochasticity. So for every “butterfly effect” there is an “envelope effect” to limit the size and scope of the downstream effect. The way the brain develops, for example, is enveloped by a small number of cell types creating a framework (radial glial cells, etc.). Their future is predictably fated. The rest of the cells populate and wire up stochastically. Culture and mating work like that. Lots of unpredictable violent actions on the individual level in a city. But it is always enveloped by space, time, and function. Much is predictable (predictive policing will tell you crime statistics down to the block, in advance). Individually, it is stochastic. Mating works the same way, in all species. Individually, it is stochastic. Observed over time the envelope of mating strategies used by each species, on average, are highly predictable. It is the subset of developmental genes that are creating that predictability. So I think we are both correct. We must see both the butterfly effect and the envelope effect, evo and devo, always operating simultaneously in any complex replicating system.

4. A: “It is that very problem that I am currently trying to deal with computationally to arrive at ways biology can display complex innate behaviors without learning. ”

This is a core question in evo-devo philosophy of biology. I would commend you to look into that literature, it may help you. As I understand instinct, it a form of evolutionary learning, but it required many previous developmental cycles, under selection. So the learning occurred in the past, by gene-protein regulatory networks, using evolution under selection, via accreting into (adding onto) the core set of developmental genes and regulatory systems (which has some heterochrony capacity, but not much). The DGT (developmental genetic toolkit) of a human is a kludge of accreted systems. We share the same trunk with many other much simpler organisms. And of course, there is also learning within the life cycle of the organism, epigenetic, individual, cultural, etc. overlaid on all this genetic learning.

I really think the evo-devo biologists are working on the most important problem for the future of AI, how do you take a cycling developmental system, give it the ability to evolve, and use that evolutionary variety under selection to keep updating (progressing) the developmental code. Part of what makes life so resilient is not just that it develops all manner of diverse forms, but that it develops higher intelligence, an intelligence which becomes *increasingly general*, increasingly able to represent anything and be useful in any context, at its leading edge of complexity. It is that *generality* of intelligence, along with its stabilizing ethics and empathy, and the knowledge accumulation and niche construction that intelligence affords, that really makes life so special, in my view.

Because of the generality of our intelligence, this acceleration train just keeps running faster, until you get postbiological life, then, as you and I both agree, you don’t even need planets, or suns. That’s a truly different state of existence, and it seems right around the corner for us, in astronomical time. We are doing a very poor job governing our planet, in many ways, as you point out. But we are also riding an accelerating train toward postbiology in the process, a train that we could not stop even if we wanted to. We are evolving unpredictably and developing predictably toward a very specific set of future capabilities. We don’t fully run the show. The universe, in my book, runs the developmental aspects of cosmic complexity, via past selection. We aren’t talking about a God or an entity here, simply the same processes that created us, and that drive certain predictable features of our own futures.

Finally, thank you for your points on randomness. It indeed is a very powerful and useful tool, all I am saying is that it is easy to overuse it. To study complex systems, I think we need a math that includes both butterfly effects and envelope effects. Consider Conway’s Game of Life. That is an interesting model, because it has developmental predictability (gliders, guns, etc.) and evolutionary randomness (not knowing where the matrix will go next, if there is randomness in initial conditions. I’m not saying the universe is a deterministic cellular automata. What I am saying is that we need models that have both functions, complex, hierarchical predictability and stochastic unpredictability. When I see only Monte Carlo methods in a model, I immediately realize there is no developmental thinking going into that model. It can describe individual and evolutionary effects quite well, but there are also environmental and developmental effects that are cumulative, on a life cycle curve (fetus, youth, maturity, replication, senescence, reycling). If we aren’t using both kinds of math in our models, we can’t accurately model long run dynamics in any system that is both evolutionary and developmental. Thanks for the conversation!

Hi Alex,

I’d like to add a bit more on the randomness point. I had a day to think about what you said here:

“randomness is a very powerful tool in computation. It solves a lot of problems in goal-seeking and optimization that breaks purely deterministic models. It should always be used as a null hypothesis to test against. I have David Raup’s book “Extinction” in which he shows that random models explain extinctions without resorting to external events, or even genetics. IOW, the idea that the 5 great extinctions are caused by cosmic or geologic events is coincidental. I don’t think that is true, but if randomness explains the extinctions, it is important to show why the extinctions are truly caused, not just coincidental, by external events.”

Thanks for this. To me this is a good example (I expect to cite it in my next book) of how easily our randomness models can be misused. They are so powerful and flexible, and so true for the great majority of contexts, that we can use them to explain all kinds of phenomena, including ones we that we know, obviously, are not fully random. There are important causal processes and constraints operating at all levels, all the time. It’s just often very hard to see their history in the daa.

One of the key things I’ve learned about the intersection of evolutionary and developmental processes in complex living systems is the 95/5 Rule. In brief, it states that on average, roughly 95% of the change is unpredictable (evolutionary), and 5% is predictable (developmental). Yet the 5% of top-down, constraining and converging processes that are in-principle predictable (if you can see and model them) are easily as important, to long range dynamics, as the 95% that are bottom-up, exploratory, stochastic and contingent. For example, 95% of metazoan genes can and do change unpredictably from one replication to the next, in any organism, and 5% are highly conserved over replications (the “conserved core” developmental genes). This has many downstream consequences that work the same way. Remember those radial glial cells I described in the developing brain? They are part of a class of only 5% of cells (actually, less) that have predetermined spatiotemporal fates, driven by those developmental genes. The rest stochastically populate, bottom-up and locally, within the constraining envelope of those top-down, global, developmentally-controlled cells. Likewise for our psychological attributes, etc. I give many other examples of this 95/5 rule in my book, including in organizations and societies. Happy to send you and any others here a PDF if helpful.

Here’s a question: If the 95/5 rule is operating in a complex system, randomness will be a valid descriptor only for 95% of events (19:1 in the sample). What is the right approach to test for the existence of a few parameters that will have downstream convergent and constraining “envelope effects” on the stochasticity of the system ? That kind of statistical test would seem to be particularly important as a *counterpart* to the null hypothesis, in probing any replicative complex adaptive system, given that it seems to describe best how development works. Planet climates are clearly a replicative system. Our universe is hugely replicative of them, in many variations.

Predictable events are always occurring in every replicative complex system, but they aren’t the simple causal processes we learned in discrete math and logic. I’d call this test the “developmental hypothesis”, and in addition to the classic NH, the DH should have to be tested in a number of variations before we’d be confident it could be rejected, if we are probing any replicative complex system. If you know of any statistical work or terms that address this topic, seeking downstream convergent and enveloping effects, based sensitively on the values of a few system parameters, I’d be grateful for the guidance. Thanks.

The late John McCarthy of AI fame once stated that intelligence was likely convergent, rather than very varied. He based his argument on what he believed the commonality of math, physics, and logic across the universe would do. One could argue that if he was right, it might be extended to your thesis of universal goodness in the universe. A consequence of that, would be to indicate that the anti-METI people are wrong, and that Zaitsev would be doing no harm in broadcasting, whether or not ETI existed during the time of humanity’s L of the Drake equation.

Thank you for this great McCarthy reference. I’ll use it in my next book. Asking what converges, on a statistically reliable basis, at various levels of evolutionary complexity, seems core to understanding the nature and future of life, intelligence, values, and adaptiveness. Just as there is a continuum of statistical predictability in complex systems, around many variables, there is continuum of structural and functional convergence.

There seem to be two convergence groups especially worth discussing. Universal convergences, expected in all systems of a certain developmental complexity, and majority convergences, expected only in the majority (the bulk of the Gaussian) in a population at that level of complexity.

Human ethics and empathy clearly have both convergence types. We all have a few developmental universals, ethical and empathic algorithms encoded as instincts, expressed in all of us in normal development. These include things like prosociality, reciprocity, and a constant search for positive-sum games we can play and enforce (see Bob Wright’s Nonzero, 2000). We also have a much larger set of majority-only convergences. Yet well-built networks (including well-built democracies) can very effectively police the sociopaths, criminals, creatives, and geniuses as long as there is a majority convergence. I think most convergence is of this weaker (not universal) type, because each individual is so limited in our intelligence. Adaptive groups always need healthy experimentation away from the norm. Sometimes the outlier is what we need, especially when conditions suddenly change.

I expect this is true for our ETs as well. Frank Drake famously said that were we to look at ET from across a darkened room, he’d expect them to look like us, in general anthropoid form (and he said implicitly, in certain ethical and empathic universals), but curiously and helpfully not like us when we turned on the light. This is the kind of careful thinking that I believe we need a lot more of in evolutionary astrobiology. It will be speculative today, but we can build better models over time, and as our computational capacities improve, simulations from first principles will increasingly settle the issue of what is universal, what is majority, and what is unpredictable and unique.

What I would add to Drake’s observation is that when we turn on the light, we should expect to find a much larger class of majority convergences, things that are still the same in most ETs in a universal population, on average, but not all. Then the largest class of observations will be all the evolutionary differences.

An important insight, from an evo-devo perspective, is that all of those evolutionary differences will be occurring *within the constraint environment* imposed by those first two classes of convergence. That means the vast majority of them will not be extreme or large enough to threaten those convergences. When we see that level of evolutionary variation biological processes, development itself fails (as in your comment about genetic abnormalities in utero, or in cancer in an adult)

From the evo-devo perspective that I favor, all of life’s evolutionary variety, in other words, occurs within and services the developmental life cycle. The better we understand the predictabilities and the hierarchies of that life cycle, the better we understand the degrees and kinds of variation and uniqueness we will see. If our universe is an evo-devo system, all the evolutionary variety of our ETs will be kept in service to the successful development (and replication) of the universe as a system, by those two classes of constraint. We shall see if any of this holds up, but it seems to me to describe part of how life, as a network, has remained so successful for so long, in so many different environments. Life has a well built core of developmental regulatory systems that have, so far, carefully harnessed evolutionary variety to keep it in service to an ever-increasing network adaptiveness, at the leading edge of complexity. It can’t do that forever, in the biological substrate, because the code is accretive, and life cannot freely edit, by and large, its developmental code. There are good arguments that life’s developmental code, now over three billion years since LUCA, is increasingly restrictive, brittle, and sclerotic, in its most complex organisms. When life goes postbiological, it will be able to edit and rejuvenate that code. That seems yet another serious adaptive advantage. Yet if evo-devo processes are at the heart of all well-built complex networks, postbiological systems will continue to live in this tension between evolutionary creativity and developmental constraint. They won’t be able to escape that universal dynamic.

To apply all this back to McCarthy’s observation, I’d like to cite the late, great mathematician Michael Atiyah, who famously said that math is both invented and discovered. We humans explore and experiment with most of our theoretical math (in an evolutionary process) and we discover and generalize with special subsets of applied math (a developmental process). To simplify, we could say that the first activity serves a universal value of Beauty, the second, of Truth. But note also that we can subdivide the “discovered math” into these two important constraint groups: There will be inevitable constraints (truths), like number theory, geometry, etc. discovered by all ETs. But there will also be only majority mathematical truths, some set of generally useful applied math that most ET civs, but not all, will discover. Then there will be a third class, a huge variety of evolutionary (creative, beautiful) theoretical maths, uniquely invented by each ET civilization, which none of us (not being omniscient or omnipotent) will be able to call true or useful, *yet.* As with our experience to date, some subset of that third category will be found true or useful, in the future, if our local environment, or the universe itself, attains some future more evolved and develop state of complexity.

To me, all this suggests the deep adaptive value of a universe that develops (self-organizes?), perhaps over many past cycles, in such a way that:

1) all the interesting intelligences are *kept spatially and informationally separated from each other,* over the great majority of their evolutionary development so that each evolves (varies) in usefully unique ways. In other words, the inaccessibility is self-organized, to benefit the whole. [PS: this is how Graafian follicles and ovulation works in the female ovary as well.]

2) has developmental laws which drive all evolved intelligences to accelerate their complexification, at the leading edge, toward a highly local, dense, and dematerialized network that looks increasingly like a black hole, or some Planck-scale structure. In other words, all the fastest growing ones go inward on average, not outward, and

3) requires all of them to exist in a universe with a special structure and topology (wormholes? Hyperspace? entanglement?) such that when we approach that black-hole-like or Planck-like domain, we all get to meet each other, and compare and contrast the limited science, intelligence and wisdom we have each obtained. All of them also learn, as their science, ethics and empathy improve, that it is best to let each civilization develop in its own unique way, to maximize local uniqueness prior to meeting and merger. [Arthur Clarke said something roughly like this, in a few of his essays].

I expect our future science to give us the outlines of these three things, long before we actually are able to “meet and greet” any ETs. My transcension hypothesis paper https://www.researchgate.net/publication/256935188_The_transcension_hypothesis_Sufficiently_advanced_civilizations_invariably_leave_our_universe_and_implications_for_METI_and_SETI describes the kind of optical SETI results that I think we will discover if this model is correct. Within a few decades, I predict our space-based SETI will see signs of Earthlikes “winking out”, and turning into something that to us, look like a black hole. It won’t be a black hole, it will be some kind of gateway to all the other ETs, but like black holes, it will be importantly outside of, and beyond, this ancient Universe, which will be simple, boring, senescent, and unaware by comparison to the complexity and consciousness that exists in all those special points (and network) of entities.

This is a lot of speculation. One day I hope we’ll see if any of it is even roughly correct. Thanks again for the comment.

If you are interested, here is the link to the SETI talk with John McCarthy. I was at that talk and got to ask a question.

Convergence of Intelligence – John McCarthy (SETI Talks)

Here is Matt Devlin giving a [partial?] counterargument.

Contact with ET using Math? Not so fast. – Keith Devlin (SETI Talks)

Thanks for sharing these. It would be interesting to see both of them debate. McCarthy would surely have laughed when Devlin wasn’t willing to concede that “any sufficiently intelligent life” wouldn’t necessarily have number theory and primes. Devlin takes Plato’s Cave way too far, into Idealism. There is a real objective world that all sufficiently advanced representation systems must find, in my view. We all use that representational grounding to build language and swap and vary memes, for example. That’s not saying that all ETs would share the same theoretical math, by any stretch. But they would all have to share core universal math, and most would share various applied maths. Just my perspective of course, feel free to disagree.

The evolution of morphology is highly contingent. If Drake is saying that of all the organisms that can attain technology that we might meet with, then only a humanoid form will work, then that is a very limited, almost anthropocentric-superior view. Far more likely is that any form that has appendages with fine manipulators and a good brain should be possible. But more importantly, he assumes ET will be biological. I think that ETs that we will meet will be machines with very different morphologies to humanoid. IOW, there is no convergence to humanoid form, either biologically, or artificial.

I disagree here. The DNA is more like a set of building blocks that can be arranged in many ways. Just as LEGO started with simple bricks, the company has diversified the range of pieces to allow a much greater variety of structures to be built. The same is true with DNA as the assembling of parts can be altered by a range of processes from breaking genes, evolving new genes, making different proteins from a single gene, turning on and off transcription promotors and enhancers, epigenetic controls, and so on. What is constrained is that each new structure must work, so it can only incrementally change from the parent. But over time we have seen an explosion of forms and capabilities. But there are constraints. IIRC Niles Eldredge thought that there were important morphological constraints and “good” forms that were not considered by the gene first proponents of evolution like Dawkins. For physical forms, there is none better than Darcy Thompson and his classic “On Growth and Form”.

Regarding Math. Mathematicians want proofs. Hence the need to prove conjectures that show universality. But the usefulness of all sorts of ideas and conjectures can be shown to be true up to a limit by brute force computations. I cannot prove Fermat’s Last Theorem (it would be so far above my capabilities), but I can write a program that can show that it holds for as many integer combinations and powers as I have computational resources as my disposal. David Gelernter has proposed this experimental approach to doing math. Whether ETI has a largely overlapping set of similar mathematical ideas or very different ones, IDK. I would be fascinated to find out what they do, as computation is likely universal and they will apply it to their problems.

IDK quite what to make of this. It seems to me that your argument about biological complexity and, rigidity, and senescence applies to this situation too. Unless they create lots of separate sub-networks that can loosely connect, then the centralized network will be likely robust but relatively static. Both biological and cultural evolution get major boosts when small populations are isolated – the “founder effect”. Change availability of alleles in small populations allows rapid evolution, through various means, such as genetic drift, whilst the big populations are constrained by the Hardy-Weinberg law. I believe the same is true of cultures. If ever there was a good reason for humans to form small colonies in widely separated space habitats it is to stimulate cultural diversity, which ultimately is more robust in toto than one large connected population that will be subject to an unexpected perturbation.

If we do transcend to another form or state, I think we must remain connected to the real universe. Even if the culture as a whole lives virtual lives, there will be those who wish to grapple with reality, just as there will always be mountain climbers tackling mountains, and not simulating those mountains in some virtual world, however real.

To mathematically capture both diversity and constraint, perhaps the math has to follow some logistic path. Early on it can model accelerate growth and test new ideas, and later converge to some constrained optimum. Technologies follow this logistic growth curve. Perhaps we need a math that can expand within this logistic envelope?

Alex: “The evolution of morphology is highly contingent.”

Yes, but there are also optimal morphologies and functions that exist that will be discovered by all that stochastic evolutionary search. We have to learn to see them and talk about them. It’s not anthropomorphic, its finding the outlines of universal development. Bilateral symmetry will win in multicellularity. That gets you to tetrapods. You only need two grasping appendages, and the ability to use them in air (not water), for collective tool use to make you dominant over all other non-tool users. There’s your anthropoid form. It’s an optimum, for all Earthlikes, sitting there in the middle of all that contingency. Dinosaurs were trending toward this form with the increasingly successful Troodon clades when the meteorite hit.

So yes, many forms are possible, but only a few will be deeply accelerative, and thus dominate their environment, via competitive exclusion. Octopi could never reach our level even though they have two prehensile limbs and can build huts, because they can’t use tools and groups to dominate their environment. Water is too dense a medium relative to the force that can be generated by creatures made of protein. Cultural acceleration had to emerge first on land, etc.

The convergence to humanoid form is only relevant to get you to the next stage of development. Yes once you have postbiological life, humans can go into any biological form. Some surely will. But will many? Or will most or all all find it by far the most valuable to migrate to postbiology? One thing is certain, the ethics and goals of the postbiologicals will drive the future at that point, if biology has an unbridgable multi-million-fold learning and action disadvantage, and all the other limitations of being dependent on biochemistry to survive.

Regarding the senescence of life’s developmental code, see figure 22 in my 2009 paper, Evo Devo Universe? here:

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/253514068_Evo_Devo_Universe_A_Framework_for_Speculations_on_Cosmic_Culture/citations?latestCitations=PB:356127378#fullTextFileContent

I’d love it if you have any feedback on any aspect of that paper (if you ever have a chance to skim it). Even life’s family origination rate has been saturating since the Cambrian. Constraint just goes up and up over time in any developing system. Not only does everything new still have to work, as you point out, it also can’t break a lot of the old legacy code its built on, and it has to compete with and adapt to increasingly complex actors and environment. Most evolutionary biologists entirely miss this process, but it is very real. I call it “terminal differentiation” in the paper. It’s just our familiar logistic curve, applied to all of biological life as a morphological explorer. I’d expect it to work the same on other Earthlikes. Within a few decades, I predict astrochemists will also know that liquid-phase organic chemistry is a unique developmental portal to complex cells, and that Earthlikes are needed to keep that chemistry stable for billennia. Many would call view that “Earth-centric”. I’d call it simply looking carefully for the special subset of circumstances that will sustain billions of years of predictable acceleration of complexity. I’m always looking for flaws in this argument however. It’s pretty speculative at present. If you find any in my paper, I’d be very appreciative to learn of them.

Thanks for the points about computation and math. Gelernter is a hero of mine. His book Mirror Worlds was very helpful to me in understanding simulation. Yes, evo-devo dynamics and life cycles, with eventual senescence, would seem to have to apply to any real physical entity, no matter how dense and dematerialized it becomes. But you know all the weird things that happen in general relativity when you get to physical extremes. When you are a near-black-hole entity, I would expect you’d surely still need to be an ecosystem of separate networks, each evolving differently yet in contact with the whole, as you point out, and you’d surely want to be in the physical world as well as in the virtual world.

But how much time would you spend in each? If the large scale physical world gets increasingly old, slow, boring and highly simulable, the more intelligent your civilization becomes, wouldn’t you spend most of your time living and experimenting in the small scale (pico, femto) physical world? And how much would you act vs “think”? As kids, we acted all day. As adults, we think much more, and act much less. Once we had enough action primitives simulated, we play much less in physical space, and much more in virtual space (imagination). This seems inevitable, as soon as the simulation gets sufficiently good. We always do both, but the ratios change, and at those extreme scales, the physical:virtual ratios may be simultaneously extreme.

I like your (implied?) idea that the math (theoretical and applied) we can learn follows a logistic path. There must be a limit to what we can learn, if we are finite creatures. The universe is big but apparently finite, and we know there is a limit to its lifespan and the acceleration that can occur. Once we hit the Planck scale, there’s no more room at the bottom for our own local acceleration. And if there is no faster than light capability, a constraint I expect is there for a very good (self-organized) reason, to keep us all evolutionarily isolated for a time, then there will be a limit to what we can all learn in a rapid timeframe. If our intelligence has been self-organized to be of use to the universe, it seems that that the big payoff, at that point, would be for all the finite understandings that each of us has made to be compared, via some way for all of us to meet each other by transcending the universe, just as the acceleration stops, rather than attempting to expand across it. We shall see if the physics bears that idea out. Thanks for the stimulating conversation Alex.

The aged, network tending people aren’t making themselves known to this youthful, network pillaging people. If this is a measure of their goodness or universal goodness, then I don’t understand how they could consider our messaging of nearby stars as good, or conscientious of the network.

Interesting topic. Consider the classic ‘The Day the Earth Stood Still.’ What is regarded as good for the cosmos might well be bad for the People of Earth, i.e., the greater good of the galaxy requires the subjugation or destruction of our planet’s unruly denizens. Also, increasing developmental consciousness would not be facilitated by walling ourselves off in a black-hole simulation but instead would be accommodated by an increase of sensitivity to the outer cosmos, as in the case of an advanced radio astronomy, that brings the ‘real’ universe to us. Beyond good and evil, we should consider if a non human intelligence in the universe will even be capable of making this kind of distinction (to be fair, we can equally well ask this of human intelligence). What would the ‘form of the Good’ be to an alien mind?

I’m reminded of Clarke’s “galaxy building” background in the odyssey series that the aliens who seeded the galaxy to cultivate mind WEEDED and well as harvested the results. In the last novel, 3001: The Final Odyssey, the plot included the idea that the monolith may have judged humans to be a species to be weeded.

Organized religion might get a severe jolt is we received a message that humanity was found forever unacceptable to join a galactic civilization and would therefore be terminated. However, if such an end was to come, I think is will be more like that of the Vogon constructor fleet demolishing Earth, except that the intelligences would no more notice us than we notice the insects during construction.

Perhaps a non-human intelligence (especially artificial) would be indistinguishable (as we see things) from evil. They (it?) would have no problem having all members on the same page because they’re equally intelligent. Here, not so much. Humans come in a wide variety of intelligence levels, and many aren’t overly bright. We have institutions like democracy guaranteeing that IQ isn’t the determining factor in voting for policies. Many of us seem to think it’s unsafe to eat GMO foods and are active in preventing GMO crops in poorer counties that really need the increased yields. At least part of this is IQ driven. An artifical intelligence wouldn’t likely be so fractured. Humans wouldn’t be able to have the universal focus.

I don’t understand why this would be the case. It certainly isn’t the case for our AIs.

IQ and voting in democracies. We have plenty of well-educated politicians and business leaders who hold very unscientific views. There is a long history of the elites wanting to restrict voting from “the masses” but I don’t think the results of this show improved outcomes, other than for the interests of those elites. Democracy seems to be the least worst approach of governance, offering a self-correcting mode. Not as self-correcting as the scientific method, but better than rule by restricted means – monarchs, oligarchs, plutocrats, etc.

Hi Project Studio,

Thank you for your great comment. It turns out, due to the way gravitational lensing works, a manufactured black hole is actually the ideal universal observational environment, via a “focal sphere” of microscopic entities orbiting it. Clement Vidal and I have both done some basic estimation work on this, based on Claudio Maccone’s great work with a Sol orbiting system. So you aren’t walling yourself off as you densify and miniaturize, you are actually becoming the best eye you can become.

What’s more, if you can miniaturize and densify your local civilization at a rate that is substantially faster than you can travel *through* the galaxy, you’re also learning, observationally, far faster by going to inner space than by sending any kind of eyes or probes into outer space. This is not to take away from all the ingenious work of many at this site, on solar sails and the like. But to me, we are in a situation similar to A E van Vogts sci-fi short, Far Centaurus, 1944 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Far_Centaurus where faster interstellar voyages were forever overtaking older programs.