Centauri Dreams tracks ongoing work on beamed sails out of the conviction that sail designs offer us the best hope of reaching another star system within this century, or at least, the next. No one knows how this will play out, of course, and a fusion breakthrough of spectacular nature could shift our thinking entirely – so, too, could advances in antimatter production, as Gerald Jackson’s work reminds us. But while we continue the effort on all alternative fronts, beamed sails currently have the edge.

On that score, take note of a soon to be available two-volume set from Philip Lubin (UC-Santa Barbara), which covers the work he and his team have been doing under the name Project Starlight and DEEP-IN for some years now. This is laser-beamed propulsion to a lightsail, an idea picked up by Breakthrough Starshot and central to its planning. The Path to Transformational Space Exploration pulls together Lubin and team’s work for NASA’s Innovative Advanced Concepts office, as well as work funded by donors and private foundations, for a deep dive into where we stand today. The set is expensive, lengthy (over 700 pages) and quite technical, definitely not for casual reading, but those of you with a nearby research library should be aware of it.

Just out in the journal Communications Materials is another contribution, this one examining the structure and materials needed for a lightsail that would fly such a mission. Giovanni Santi (CNR/IFN, Italy) and team are particularly interested in the question of layering the sail in an optimum way, not only to ensure the best balance between efficiency and weight but also to find the critical balance between reflectance and emissivity, because we have to build a sail that can survive its acceleration.

What this boils down to is that we are assuming a laser phased array producing a beam that is applied to an extremely thin, lightweight structure, with the intention of reaching a substantial percentage (20 percent) of lightspeed. The laser flux at the spacecraft is, the paper notes, on the order of 10 – 100 GW m-2, with the sail no further from the Earth than the Moon. Lubin’s work at UC-Santa Barbara (he is a co-author here) has demonstrated a directed energy source with emission at 1064 nm.

Thermal issues are critical. The sail has to survive the temperature increases of the acceleration phase, so we need materials that offer high reflectance as well as the ability to blow off that heat, meaning high emissivity in the infrared. The Santa Barbara laboratory work has used ytterbium-doped fiber laser amplifiers in what the paper describes as a ‘master oscillator phased array’ topology. And this gets fascinating from the relativistic point of view. Remember, we are trying to produce a spacecraft that can make the journey to a nearby star in a matter of decades, so relativistic effects have to be considered.

In terms of the sail itself, that means that our high-speed spacecraft will quickly see a longer wavelength in the beamed energy than was originally emitted. This is true despite the fact that the period of acceleration is short, on the order of minutes.

The authors suggest that there are two ways to cope with this. The laser can shorten its emission wavelength as the spacecraft accelerates, meaning that the received wavelength is constant. But the paper focuses on a second option: Make the reflecting surface broadband enough to allow a fairly large range of received wavelengths.

Thus the core of this paper is an analysis of the materials possible for such a sail and their thermal properties, keeping this wavelength change in mind, while at the same time studying – after the operative laser wavelength is determined – how the structure of the lightsail can be engineered to survive the extremities of the acceleration phase.

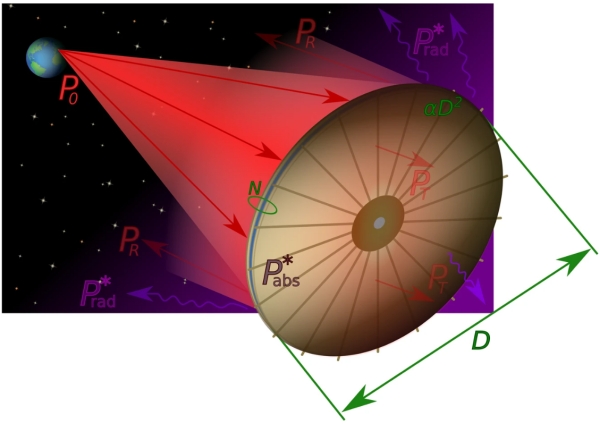

Image: This is Figure 1 from the paper. Caption: The red arrows denote the incident, transmitted and reflected laser power, while the violet ones indicate the thermal radiation leaving the structure from the front and back surfaces. The surface area is modeled as ?D2; ??=?1 for a squared lightsail of side D and ??=??/4 for a circular lightsail of diameter D. Credit: Santi et al.

The paper considers a range of possible materials for the sail, all of them low in density and widely used, so that their optical parameters are readily available in the literature. Optimization is carried out for stacks of different materials in combination to find structures with maximum optical properties and highest performance. Critical parameters are the reflectance and the areal density of the resulting sail.

Out of all this, titanium dioxide (TiO2) stands out in terms of thermal emission. This work suggests a combination of stacked materials:

The most promising structures to be used with a 1064?nm laser source result to be the TiO2-based ones, in the form of single layer or multilayer stack which include the SiO2 as a second material. In term of propulsion efficiency, the single layer results to be the most performing, while the multilayers offer some advantages in term[s] of thermal control and stiffness. The engineering process is fundamental to obtain proper optical characteristics, thus reducing the absorption of the lightsail in the Doppler-shifted wavelength of the laser in order to allow the use of high-power laser up to 100 GW. The use of a longer wavelength laser source could expand the choice of potential materials having the required optical characteristics.

So much remains to be determined as this work continues. The required mechanical strength of the multilayer structure means we need to learn a lot more about the properties of thin films. Also critical is the stability of the lightsail. We want a sail that survives acceleration not only physically but also in terms of staying aligned with the axis of the beam that is driving it. The slightest imperfection in the material, induced perhaps in manufacturing, could destroy this critical alignment. A variety of approaches to stability have emerged in the literature and are being examined.

The take-away from this paper is that thin-film multilayers are a way to produce a viable sail capable of being accelerated by beamed energy at these levels. We already have experience with thin films in areas like the coatings deposited on telescope mirrors, and because the propulsion efficiency is only slightly affected by the angle at which the beam strikes the sail, various forms of curved designs become feasible.

Can a sail survive the rigors of a journey through the gas and dust of the interstellar medium? At 20 percent of c, the question of how gas accumulates in materials needs work, as we’d like to arrive at destination with a sail that may double as a communications tool. Each of these areas, in turn, fragments into needed laboratory work on many levels, which is why a viable effort to design a beamed mission to a star demands a dedicated facility focusing on sail materials and performance. Breakthrough Starshot seems ideally placed to make such a facility happen.

The paper is Santi et al., “Multilayers for directed energy accelerated lightsails,” Communications Materials 3 (16 (2022). Abstract.

Something that may be another way to protect the sail is a plasma generated on the surface of the sail. Reading about X-ray laser an interesting effect was suggested where the material used to lase was also used as the absorber plasma at the receiving end. The space based X-ray laser would have an accelerator that could raise the frequency as the sail accelerated. Because the K electron shell closet to the nucleus absorbs the X-ray energy the propulsion may very effective and powerful. If the frequency is tuned correctly the X-rays may be totally absorbed by the plasma…

if an X-ray laser can be made

Charlie where have you been?

Building the world’s brightest X-ray laser.

The LCLS-II laser will be 10,000 times brighter than its predecessor.

https://www.cnet.com/science/building-the-worlds-brightest-x-ray-laser/

Table-top soft X-ray laser in the ‘water window’.

https://researchoutreach.org/articles/table-top-soft-x-ray-laser-in-the-water-window/

18 April 2021

Laser-driven compact free electron laser: from extreme ultraviolet radiation to x-rays.

https://www.spiedigitallibrary.org/conference-proceedings-of-spie/11777/117770N/Laser-driven-compact-free-electron-laser–from-extreme-ultraviolet/10.1117/12.2591994.short

China on brink of laser-matter breakthrough.

https://asiatimes.com/2021/05/china-on-brink-of-laser-matter-breakthrough/

“Station of Extreme Light” –‘A New Physics That Can Tear Apart the Fabric of Spacetime’.

https://dailygalaxy.com/2021/05/chinas-station-of-extreme-light-a-new-physics-that-can-tear-apart-the-fabric-of-spacetime-todays-most-popular/

Wikipedia:

“An X-ray laser is a device that uses stimulated emission to generate or amplify electromagnetic radiation in the near X-ray or extreme ultraviolet region of the spectrum, that is, usually on the order of several tens of nanometers (nm) wavelength.

Because of high gain in the lasing medium, short upper-state lifetimes (1–100 ps), and problems associated with construction of mirrors that could reflect X-rays, X-ray lasers usually operate without mirrors; the beam of X-rays is generated by a single pass through the gain medium. The emitted radiation, based on amplified spontaneous emission, has relatively low spatial coherence. The line is mostly Doppler broadened, which depends on the ions’ temperature.”

” … and problems associated with construction of mirrors that could reflect X-rays, X-ray lasers usually operate without mirrors; the beam of X-rays is generated by a single pass through the gain medium. ”

Maybe out-of-date; but ‘ …X-ray lasers usually operate without mirrors; the beam of X-rays is generated by a single pass through the gain medium. ‘ seems like a one-shot deal.

Didn’t the SDI “Star Wars” program have ideas for X-ray lasers using nuclear weapons as the pulsed energy source to generate the X-rays for the lasers? The targets would be acquired, the bomb triggered and multiple X-ray beams disable the targets. Definitely, a “one-shot” weapon, although it could hit multiple targets if it worked.

Hi Alex

The rumour was that the x-ray laser was tested in an underground test and failed rather dismally. Prior to the test, Edward Teller was bullish about the x-ray laser as an “Ultimate Defense” and went quiet after the test.

Wasn’t talking about bombs; how does a “one-shot” work for light sails ?

Good point, but here is an example of how fast the field is advancing:

Population inversion X-ray laser oscillator.

https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.2005360117

Use the X-ray energy contained in the beam to energize a propellant for propulsion or a material used to lase was also used as the absorber plasma at the receiving end.

“Pulsed Ablative-Plasma rockets have the highest exhaust velocities. Terawatt-level pulsed lasers depositing megajoule level pulses in microgram masses of propellant can create temperatures exceeding hundreds of billions of kelvin. Using the root mean square velocity of the gasses, we can estimate the exhaust velocity.”

For hydrogen (1g/mol, 22J/g/K), we can get 33672 km/s out of a 45.5 billion K gas, but it is hard to store.

Lithium (6g/mol, 3.56J/g/K) can produce an exhaust velocity of 34173km/s out of a 281 billion K gas.

Carbon (6g/mol, 0.52J/g/K) is the easiest to build a Pulsed Ablative-Plasma rocket out of, and reaches 63223km/s exhaust velocity from of a 1923 billion K gas.

Interstellar Trade Is Possible Part II: Travel.

http://toughsf.blogspot.com/2017/04/interstellar-trade-is-possible-part-ii.html

X-ray lasers can not penetrate through the earth’s atmosphere, so in orbit. No death rays for dictators or peasants and it can reach interstellar distances with a small beam and strength. Maybe a solar power desktop X-ray transmitter from Alpha Centauri A back to earth…

So we just had a post where the suggestion was to build the sail with a “parachute” design, almost a hemisphere, to best stay aligned and able to withstand the forces.

2 papers were discussed. The first used a film made of

, and the second was designed for high emissivity using a grid design, rather than a solid film.

Delving into the Interstellar Sail

In a relatively few short years we seem to be making a lot of headway in the research for designing these types of small, beamed sails.

Whether we manage to solve all of the problems for interstellar probes, I think we will have some interesting possibilities for exploring our solar system with these sails for very rapid propulsion of larger payloads to many targets that will provide a deluge of detailed data that we have not been able to acquire before with the emphasis on single probes and long planning and mission horizons. Also, just imagine the response possible to another transient visitor like ‘Oumuamua.

“Also, just imagine the response possible to another transient visitor like ‘Oumuamua.” Alex Tolley

Great point. On the way to development of a 20 percent of c beamed sail system, a system with a less powerful phased array laser and less demand on the sail material would open lots of new mission possibilities. So what would be required to catch `Oumuamua itself?

“So what would be required to catch `Oumuamua itself?”

So by catch, u mean fly by at 20 % light speed ?

Possible with a two stage sail, the main one to accelerate and a second stage that is pulsed with laser light near the catch up point and concentrated to slow a smaller sail into orbit around it.

I don’t think it is necessary to have complex multi layer sails, gratings can be very reflective and open structured to aid emission of heat.

https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/0957-0233/17/5/S12

The materials I have every confidence in been made, however the shear size of the laser array is daunting. If perhaps we could have a lens and properly designed mirror we could use multi bounce to reduce the capital expense of such a large system. If we had the mirror and lens and sail in a highly elliptical orbit as it returns to earth a laser beam is shone through the central lens and it bounces off the sail and mirrored surface. Although as the sail become more relativistic to the mirror it is less useful it would be very useful in testing sail materials and controls as well as allow for more slower probes around the solar system or solar lens line.

Chinese astronomers are joining the effort to find other Earth-like planets, their proposal for space based telescope is quite impressive and will also work on refining the data obtained by Kepler telescope. If approved the mission would launch in 2026.

https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-022-01025-2

“The Earth 2.0 satellite is designed to carry seven telescopes that will observe the sky for four years. Six of the telescopes will work together to survey the Cygnus–Lyra constellations, the same patch of sky that the Kepler telescope scoured. “The Kepler field is a low-hanging fruit, because we have very good data from there,” says Jian Ge, the astronomer leading the Earth 2.0 mission at the Shanghai Astronomical Observatory of the Chinese Academy of Sciences.

The telescopes will look for exoplanets by detecting small changes in a star’s brightness that indicate that a planet has passed in front of it. Using multiple small telescopes together gives scientists a wider field of view than a single, large telescope such as Kepler. Earth 2.0’s 6 telescopes will together stare at about 1.2 million stars across a 500-square-degree patch of sky, which is about 5 times wider than Kepler’s view was. At the same time, Earth 2.0 will be able to observe dimmer and more distant stars than does NASA’s Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS), which surveys bright stars near Earth.

“Our satellite can be 10–15 times more powerful than NASA’s Kepler telescope in its sky-surveying capacity,” says Ge.”

(…)

four years into the Kepler mission, parts of the instrument failed, rendering the telescope unable to stare at one patch of the sky over an extended period of time. Kepler was on the cusp of finding some truly Earth-like planets, says Huang, who has worked with the Earth 2.0 team as a data-simulation consultant.

With Earth 2.0, astronomers could have another four years of data that, when combined with Kepler’s observations, could help to confirm which exoplanets are truly Earth-like. “I am very excited about the prospect of returning to the Kepler field,” says Christiansen, who hopes to study Earth 2.0’s data if they are made available.

Ge hopes to find a dozen Earth 2.0 planets. He says he plans to publish the data within one or two years of their collection. “There will be a lot of data, so we need all the hands we can get,” he says. The team already has about 300 scientists and engineers, mostly from China, but Ge hopes more astronomers worldwide will join. “Earth 2.0 is an opportunity for better international collaboration.”

Thanks!

I have a couple of layman’s questions about the multi-layer sail concept. Would a multi-layer sail allow the “shedding” of a layer as damage due to interstellar collisions with gas molecules etc. occurs as well as optimizing sail performance with layers composed of different materials as the wavelength of the laser light gets red shifted? It sounds like a brilliant concept.

That’s a good question and I’m afraid I don’t know the answer, but let me ask Phil Lubin about it.

An ablative layer might give a rocket push-thinning to fragile then when far from the laser.

AFAICS, once the minutes-long acceleration stage has ended, there is no further value of the sail as a propulsion unit. It seems to me that after acceleration, the best use of the sail would be to redeploy it as a shield for the payload. Assuming the payload has a far smaller frontal area than the sail, the sail should fold in on itself to provide the best shield possible, whether as a tightly folded sail or a loosely folded one acting more like a Whipple shield. This might be particularly useful as the probe enters the target system where the density of particles is higher and likely to be more damaging to the probe. After data collection, the sail should then redeploy to form a concave antenna to focus the data transmission back to earth, either directly, or once it has reached the gravity focal line and positioned directly to send the data to Earth.

If the sail cannot be folded, then just design it to optimize the acceleration phase and the data transmission, leaving the sail as is to shield the probe from damage in the ISM and at the target system, possibly traveling edge on to maximize the mass between the payload and the incoming particles.

It could be used as a comm dish…a feed horn at the focus.

1) what laser can hit at that accuracy?

2) not intended to slow down?

About that gigawatt laser…

How much is this laser going to cost?

Who is going to fund it? A business consortium? Universities? Governments? All three?

How much in terms of acreage and resources is it going to need?

Will it be built on Earth or in space? In either case, where would be the best places for it?

How will this laser be kept from being turned into a weapon? Current events show this is not a paranoid concern.

Who will guard and monitor the gigalaser? Please do not tell me the United Nations.

Can such a laser be kept running AND stay focused on a light sail as it crosses interstellar distances for decades?

Please either discuss these questions here or point me to where they have already been considered, thank you.

I still think some form of Orion nuclear pulse vessel would be relatively easier and quicker, but let’s play with the megapowerful laser that has never been built for such a purpose before first.

The laser is not going to be used across interstellar space. The range is not much further than the Moon, hence the need for a powerful laser, a short acceleration period, and very high g forced on the sail. [At least that is the Breakthrough Starshot approach AIUI.]

Location, on Earth, is in the high desert of Peru, where the sky is clear, the air dry, and thin[ner]. Same locations at the telescopes, but using lots of acreage. Even with SpaceX Starship, the cost of space location multiplies the costs. Maybe if we can build solar arrays on the Moon and ship them to Earth orbit, the cost could be mitigated somewhat.

A phased laser array in the Southern hemisphere, on the surface, is not a good place for a weapon as it cannot easily hit interesting targets. Worse, it is a sitting duck as a target for suborbital, partial orbital weapons, and hypersonic cruise missiles. [Remember when Reagan wanted to move ICBMs around to reduce the vulnerability of fixed position silos?]

Cost is still going to be very high. But it is reusable for many, many launches of sails, from tiny to larger, and with differing payload sizes (see Lubin’s roadmap). The comparison should be made between the total cost of construction, maintenance, and and operation including electric supply, for the various missions, and the alternative. [Even Orion cannot reach 0.2 c which ensures that laser sail missions have a least one performance case that cannot be met by the Orion technology.] For comparable mission velocities, what is the cost comparisons for total payload masses of many beamed sails vs Orion? How many targets can be reached? What is the scientific return of the 2 approaches. I think there are likely to be pros and cons for each approach depending on the desired science goals. Is there a hybrid option where a large ship like Orion carries the laser array and sail probes, distributing them once it reaches its target to gain the spatial coverage?

@ljk

Intergration of the laser system is a must if it is pay for itself, it can be used to melt the surface of the Moon and allow under ground dwellings, roads and flat surfaces for solar cells for perhaps retransmission back to earth. It can also be used to push craft to the moon, land and back again. Without this Intergration into a wide system no one will foot the bill.

The atoms that hit the sail which is edge on could be used to power the probe as they will be ionized with parts of the sail sputtered off.

OT.

@Michael Fidler. Doesn’t this story indicate the DoD does track meteors?

US military confirms an interstellar meteor collided with Earth

Oh, Yes Alex…

The meaning of BOLIDE is a large meteor : fireball; especially : one that explodes.

And so does the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

https://neo-bolide.ndc.nasa.gov/#/

So if I had used the term bolide or fireball, you would have said: “Of course, NORAD tracks those”? ;)

There are potentially a huge number of modes a primary interstellar sailing craft could use. Some of these are sailing modes and others are non-sail propulsion systems that would augment interstellar sails. I have four published books on the subject which are huge e-books of PC downloadable PDFs. The books range from a few hundred thousand pages to on the order of one million pages each. The reason the books are so lengthy is that they provide numerical algorithms for computing the Lorentz factors of the sails.

Interstellar sails are likely about as good as any other relativistic propulsion mechanism. Likely, interstellar sails should have secondary propulsion modes such as relativistic rockets and the like for finer course correction.

Currently, I am working on my 5th book on space sails.

Light-sails are really cool. I like to view them as somewhere in the exotic between still conjectural mechanisms of warp drive, wormhole transport and the like and reactionary thrust systems such as rockets.

Light-sails can actually work as The Planetary Society’s Light Sail 1, 2, and 3 indicate.

Lightsail as used by the Planetary Society is a straightforward solar sail. I usually use ‘lightsail’ to refer to sails with beamed propulsion of some kind, as I think is fairly common in the literature.

Thanks for the clarification Paul. It is wise for folks into this stuff to use correct language. So I welcome the corrections.

Regarding Lightsail-3, although a bit off topic, have you any more details about when it will launch. Last time I checked Lightsail-3 online, all I could find is the reports for Lightsail 1 and 2.

None-the-less, the materials developed for Lightsail 1 and 2 might have relevance for beamed power sails. A good example would include a system of inflatable or otherwise rigidizable membranous optics that focus sunlight into a very powerful beam but one that obtains its power not so much for areal flux density but instead a large cross-sectional area.

My brother John and I obtained patents for a variety of solar energy concentrators and obtained a mass specific power density of 10 kilowatts per kilogram and solar light concentration factor of over 100. These were meant to be solar cookers and solar heaters but we included scenarios for space-based use.

All our patents expired as we could not afford the maintenance fees or the times of patent duration expired.

I’m not aware of any Planetary Society plans for a third LightSail.