While we talk often about subsurface oceans in places like Europa, the mechanisms for getting through layers of ice remain problematic. We’ll need a lot of data through missions like Europa Clipper and JUICE just to make the call on how thick Europa’s ice is before determining which ice penetration technology is feasible. But it’s exciting to see how much preliminary work is going into the issue, because the day will come when one or another icy moon yields the secrets of its ocean to a surface lander.

By way of comparison, the thickest ice sheet on Earth is said to reach close to 5,000 meters. This is at the Astrolabe Subglacial Basin, which lies at the southern end of Antarctica’s Adélie Coast. Here we have glacial ice covering continental crust, as opposed to ice atop an ocean (although there appears to be an actively circulating groundwater system, which has been recently mapped in West Antarctica). The deepest bore into this ice has been 2,152 meters, a 63 hour continuous drilling session that will one day be dwarfed by whatever ice-penetrating technologies we take to Europa.

Consider the challenge. We may, on Europa, be dealing with an ice sheet up to 25 kilometers thick – figuring out just how thick it actually is may take decades if the above missions get ambiguous results. In any case, we will need hardware that can operate at cryogenic temperatures in a hard vacuum, with radiation shielding adequate to the Jovian surface environment. The lander, after all, remains on the surface to sustain communications with the Earth.

Moreover, we need a system that is reliable, meaning one that can work its way around problems it finds in the ice as it moves downward. Here again we need ice profiles that can be developed by future missions. We do know the ice we encounter will contain salts, sulfuric acids and other materials whose composition is currently unknown. And we will surely have to cope with liquid water ‘pockets’ on the way down, as well as the fact that the ice may be brittle near the surface and warmer at greater depths.

SESAME Program Targets Europan Ice

NASA’s SESAME program at Glenn Research Center, which coordinates work from a number of researchers, is doing vital early work on all these problems. On its website, the agency has listed a number of assumptions and constraints for a lander/ice penetrator mission, including the ability to reach up to 15 kilometers within three years (assuming we learn that the ice isn’t thicker than this). For preliminary study, a total system mass of less than 200 kg is assumed, and the overall penetration system must be able to survive three years of operations in this hostile environment.

So far this program is Europa-specific, the acronym translating to Scientific Exploration Subsurface Access Mechanism for Europa. The idea is to identify which penetration systems can reach liquid water. It’s early days for thinking about penetrating Europa and other icy moon oceans, but you have to begin somewhere, and SESAME is about figuring out which approach is most likely to work and developing prototype hardware.

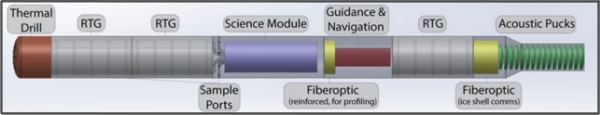

SESAME is dealing with proposals from a number of sources. Johns Hopkins, for example, will be testing communication tether designs and analyzing problems with RF communications. Stone Aerospace is studying a closed-cycle hot water drilling technology running on a fission reactor. Georgia Tech is contributing data from projects in Antarctica and studying a subsurface access drill design, hoping to get it up to TRL 4. Honeybee Robotics is focused on a “hybrid, thermomechanical drill system combining thermal (melting) and mechanical (cutting) penetration approaches.”

Image: A preliminary VERNE design from Georgia Tech showing conceptual component layout. Credit: Georgia Tech.

We’re pretty far down on the TRL scale (standing for Technology Readiness Level), which goes from 1 to 9, or from back of the cocktail lounge napkin drawings up to tested flight-ready hardware. Well, I shouldn’t be so cavalier about TRL 1, which NASA defines as “scientific research is beginning and those results are being translated into future research and development.” The real point is that it’s a long haul from TRL 1 to TRL 9, and the nitty gritty work is occurring now for missions we haven’t designed yet, but which will one day take us to an icy moon and drill down into its ocean.

Swarming Technologies at JPL

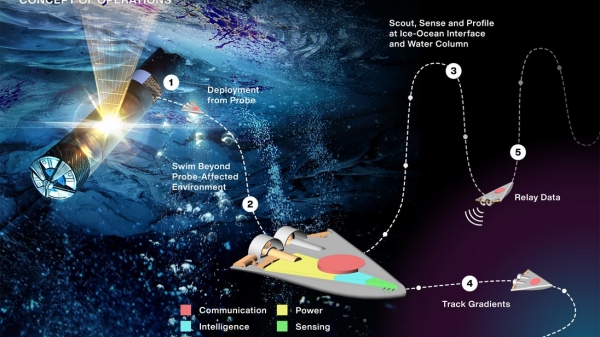

Let’s home in on work that’s going on at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, in the form of SWIM (Sensing With Independent Micro-Swimmers), a concept that, in the hands of JPL’s Ethan Schaler, has just moved into Phase II funding from NASA’s Innovative Advanced Concepts program. The $600,000 award should allow Schaler’s team to develop and test 3D printed prototypes over the next two years. The plan is to design miniaturized robots of cellphone size that would swarm through subsurface oceans, released underwater from the ice-melting probe that drilled through the surface.

Schaler, a robotics mechanical engineer, focuses on miniaturization because of the opportunity it offers to widen the search space:

“My idea is, where can we take miniaturized robotics and apply them in interesting new ways for exploring our solar system? With a swarm of small swimming robots, we are able to explore a much larger volume of ocean water and improve our measurements by having multiple robots collecting data in the same area.”

Image: In the Sensing With Independent Micro-Swimmers (SWIM) concept, illustrated here, dozens of small robots would descend through the icy shell of a distant moon via a cryobot – depicted at left – to the ocean below. The project has received funding from the NASA Innovative Advanced Concepts program. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech.

We are talking about robots described as ‘wedge-shaped,’ each about 12 centimeters long and 60 to 75 cubic centimeters in volume. Space is tight on the cryobot that delivers the package to the Europan surface, but up to 50 of these robots could fit into the envisioned 10-centimeter long (25 centimeters in diameter) delivery package, while leaving enough room for accompanying instruments that will remain stationary under the ice.

I mentioned the Johns Hopkins work on communications tethers, and here the plan would be to connect to the surface lander (obviously ferociously shielded from radiation in this environment), allowing an open channel for data to flow to controllers on Earth. The swarm notion expands the possibilities for what the ice penetrating technology can do, as project scientist Samuel Howell, likewise at JPL, explains:

“What if, after all those years it took to get into an ocean, you come through the ice shell in the wrong place? What if there’s signs of life over there but not where you entered the ocean? By bringing these swarms of robots with us, we’d be able to look ‘over there’ to explore much more of our environment than a single cryobot would allow.”

Image: This illustration shows the NASA cryobot concept called Probe using Radioisotopes for Icy Moons Exploration (PRIME) deploying tiny wedge-shaped robots into the ocean miles below a lander on the frozen surface of an ocean world. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech.

One of the assumptions built into the SESAME effort is that the surface lander will use one of two nuclear power systems along with whatever technologies are built into the penetration hardware. Thus for the surface cryobot we have the option of a “small fission reactor providing 420 We and 43,000 Wth waste heat” or a “radioisotope power system providing up to 110 We and 2,000 Wth waste heat.” SWIM counts on nuclear waste heat to melt through the ice and also to produce a thermal bubble whose reactions with the ice above could be analyzed in terms of water chemistry.

The robots envisioned here have to be semi-autonomous, each with its own propulsion system, ultrasound communications capability and basic sensors, including chemical sensors to look for biomarkers. Overlapping measurements should allow this ‘flock’ of instrumentation to examine temperature or salinity gradients and more broadly characterize the chemistry of the subsurface water. We’ll follow SWIM with interest not only in the context of Europa but other ocean worlds that may be of astrobiological significance. If life can exist in these conditions, just how much biomass may turn up if we consider all the potential ice-covered oceans on moons and dwarf planets in the Solar System?

Hi Paul

Yes some very interesting missions, I’d like to see a surface lander to Europa planned in the near future.

And just as your email arrived in I was reading the following papers.

Different ice shell geometries on Europa and Enceladus due to their different sizes

https://arxiv.org/abs/2206.15325

Dynamics or Geysers and tracer transport over the south pole of Enceladus

https://arxiv.org/abs/2205.15732

Energetics govern ocean circulation on icy ocean worlds

https://arxiv.org/abs/2206.00732

Tidal insights into rocky and icy bodies

https://arxiv.org/abs/2206.04370

Laboratory Experiments on the Radiation Astrochemistry of Water Ice Phases

https://arxiv.org/abs/2206.11614

Cheers Edwin

By the way, thanks for this material!

If the robotic probes can be kept warm, then the only serious exposure is to the radiation in the Jupiter system. Once the drill gets well below the surface, the radiation exposure is eliminated. Once in the subsurface ocean, the environment is likely to be almost benign. BUT…do we expect the ocean surface pressure to be what would be expected with 25 km of ice “floating” on top of it?

IDK how the probes are intended to communicate back to the surface, radio won’t work. ROVs are generally tethered AFAIK.

I would hope that several of the probes are able to descend towards the ocean bottom recording conditions as they go. It would be a bonus if the drilling was over a hotspot that was caused by a hot ocean vent, as this is where we might best encounter life, should there be any.

Maybe the cryobot would not have to go the bottom of the ocean but stay near the ice layer above it in order to get useful information.

It might, but can we detect life in terrestrial hot vents with samples at the surface? Life is most prolific at optimal temperatures for their biology, and near-freezing water is nowhere near-optimal. A robot that can sink down to the seabed, preferable over a vent, could take physical readings throughout the water column, and samples of the water, as well as a seabed sample that might be a haven for bacteria. The difficulties include being over a hot spot, surviving the pressure at depth, and communicating any results, or returning to a collection point for retrieval and analysis by an equipped lander.

Some kind of onboard chemical laboratory could take a sample of the frozen ice which was from the cryovolcano crater opening and detect biomolecules, the DNA Chonps Carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, phosphorous and sulfur assuming there is a enough biomolecules so they would be in the water vapor from a hot spot in the ocean.

I am not sure if any kind of spectrometer can detect DNA in water vapor, maybe a mass spectrometer?

Why not assume a 100 ton payload as per Starship? We are already almost there this year. No need to pussyfoot about. Oh, and do something NASA never does – take a lab with microscopes.

The extra mass comes in useful (I have read that Starship is capable of carrying 80 tons to Jupiter, but have not verified the numbers). But the future of space exploration is not just extra mass, it is deploying smaller interconnected devices that can cover large areas, instead of concentrating all the power on a single target.

By the way, from working in the field I get the sense that people are waiting to see Starship successfully launch a few times before it will be taken seriously. Elon Musk makes a lot of claims, but it is hard to commit serious money and time without solid proof it works.

wouldn’t the drill hole collapse due to shifting ice ?

Maybe. The pressures at depth, ice state and mineral impurities must be known. But I suspect you may be right that the hole will not be stable, movement or not.

Maybe an orbiter with several different spectrometers including infra red can tell us if the cryovolcanoes are active and if there is any water vapor in their plumes. The cryobot idea is very innovative. The problem with a cryobot is that there is no way to get the information from it one it is in an ocean with such thick ice blocking any transmission of data with radio waves. Maybe it would have to have cameras and radar to be right under the volcano, so the radio transmissions could get to the surface. Another idea is sonar, which goes through water. If the cryovolcanoes are active, a lander with can sample the water or ice from it is the cheapest way to get information about the ocean beneath the ice on Europa. No doubt in the distant future, we will be able to move equipment there which could drill through the ice.

It looks like the proposed vehicles employ acoustic pucks for communicating to the surface.

https://trs.jpl.nasa.gov/bitstream/handle/2014/54751/CL%2321-1437.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

There’s no reason the cryobot can’t trail an optic fiber cable behind it as it descends through the ice, or possibly a few isotope battery powered acoustic relay stations. Especially if you forget NASA’s usual miserly mass budget, and assume use of a Starship.

An enabling technology we should really revive for use in probes around the gas giants is the ‘integrated vacuum tube’; It uses the same etching and deposition techniques used to make integrated circuits to manufacture chips composed of microscopic vacuum tubes using field emission instead of heated emitters.

They’re perhaps not as small as current semiconductor transistor gates, nor as energy efficient, but they’re actually faster, and incredibly radiation tolerant.

https://www.science.org/content/article/return-vacuum-tube

25 km of optic cable? Calculate the weight of suitably armored cable that is to be transported, landed and deployed. The cable must also withstand the tension of 25 km of it hanging from the surface anchor, even considering the lower gravity.

The proposed “wireless” acoustic pucks are far lighter and entail far less risk during deployment and use.

A series of “pucks” makes more sense than a continuous cable if you’re worried about ice movements, dangling cables or things being crushed. When reading concerns about a long cable it occurred to me that you could use a chain of relays instead, and of course it had been thought of. The rate of transmission might not be “swift as an arrow from Tartar’s bow”, but hopefully it will work . If they ever drilled Titania and Oberon, “pucks” would be appropriate :-) .

“swift as an arrow from Tartar’s bow”?Perhaps Shakespeare was unacquainted with the Americas.

I would like to find out more about the capabilities of these robots using ultrasound for communication. I can find little literature on ultrasound communication. With velocities in the range of a few km/s, there is going to be a latency issue for any robot straying far from the receiver or transmitter. Bandwidth is limited too. Does this imply that the robots will use ultrasound primarily for control and navigation and not for the transmission of high bandwidth data? (Temperature, pH, salinity: yes, but images: no). With the depth of the subsurface ocean, how far/deep could a robot probe go and still remain in communication with a transmitter/receiver at the ocean-crust interface? Could this be extended using relays of robots?

The other issue is power. How will these small robotic craft be powered? Batteries seem likely. What would the expected range of such a robot be? Is the distance limited by battery energy storage or communication distance?

I might try one of the Tiger stripes to see if I could roll something down there.

Expand…warm…roll…expand…warm….roll.

Perhaps use a UV laser and fibre optic lead instead to breakdown the ice into gases that escape the hole, no need to worry about refreezing ice.

Your worry isn’t refreezing, it’s the ice creeping closed, and when you reach the liquid water, that water shooting up the hole.

You actually need the ice freezing again behind the probe to prevent that latter.

The ambient temperature is too low. It will likely be only seconds before the vapor condenses and then refreezes. Evacuating the material will not be easy, and vaporizing it can cause more severe difficulties than removing granular solids from a drill bit or other mechanical device.

The water is photo dissociated into oxygen and hydrogen which escapes as gases. Water can come up the column to be examined by on board systems and the fibre optic allows us to see at the bottom of the hole.

Looking at the 3rd image in Paul’s article it looks like there is some kind of relay from the Verne to the surface lander for communications.

The “EmberCore” from Ultra Safe Nuclear would be the new safer RTG generator for such probes. It should be available by 2027 and these probes look to be developed in the 2030 period.

Next Generation Radioisotope Nuclear Space Propulsion in the 3-Kilowatt Range.

June 28, 2022

https://www.nextbigfuture.com/2022/06/next-generation-radioisotope-nuclear-space-propulsion-in-the-3-kilowatt-range.html

Ultra Safe Nuclear.

https://usnc.com/EmberCore/

I hope the long time scale of this project will encourage more basic science before researchers resort to melting their way down through 25 km of ice with a hot nuclear reactor. This project speaks directly to a crucial invention we’re lacking: a cheap, efficient means to tunnel through bulk material. In thermodynamic terms, we should need no energy at all to send a dense probe down into Europa. It should be able to unmake ice in front of it and remake it behind it with no significant change in enthalpy.

Of course, I have no idea how we’d do that. But I’d hazard a guess that the kind of acoustic holography that can levitate particles through the air (see https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.abn7614 ) might one day allow blocks of ice to be cheaply and cleanly fractured from in front of the probe and moved to a position behind it, without heating them. Perhaps there is a way to “enzymatically” make cryogenic ice act like water when in contact with a probe, moving it around in a special surface environment without heating it. Something.

In any case, I’m pretty convinced living organisms can do something somewhat similar. There are absurd stories ( https://www.extremetech.com/extreme/335724-spore-in-the-core-830-million-year-old-microbes-in-rock-salt-might-be-alive ) that claim that bacteria can stay alive through 830 million years of background radiation exposure without so much as an energy source let alone a chance to reproduce. I don’t believe a word of it – I’d much sooner believe they are able to move through solid halite! Maybe they could teach us what we need to know.

We need similar but more advanced technology for transportation routes, nuke-proof infrastructure, containment of polluting industry, preservation of threatened biomes, and just plain living room for a growing population. If NASA can get the ball rolling with an efficient ice borer, it will already have great advantages for Antarctic research. All we need is for somebody … to figure it out!

I think this may be the answer;

Gyrotron beams, Quaise!

Tapping into the million-year energy source below our feet

MIT spinout Quaise Energy is working to create geothermal wells made from the deepest holes in the world.

Zach Winn | MIT News Office

Publication Date:June 28, 2022

https://news.mit.edu/2022/quaise-energy-geothermal-0628

This is interesting, but not what I’m hoping for. The rock still has to be vaporized, requiring a large energy source. It is still up in the air whether the vaporized rock will escape the hole before it condenses to liquid and eventually freezes, and the deeper the hole the harder the problem.

Contrast an “enzymatic” approach, where a catalyst would bind reversibly to ions at the surface of the stone, providing the activation energy to separate them from its internal structure or coenzymes, and then regenerate that energy by depositing them on another surface. Such a process, if perfectly efficient, conceptually uses no net energy at all. (The need for some sort of allosteric or “optogenetic” regulation means it won’t be perfectly efficient; you don’t want to merely diffuse the stone but to move it irreversibly in one direction) Now, I doubt an enzyme from Earth life can do this (though they may offer surprises), but synthetic biology is moving rapidly toward a place where protein-like structures with new functional groups might be able to do things that our proteins wouldn’t dream of. Alternatively, there may be some clever way to do this with a conventional chemical catalyst or good physical engineering – anything that can deliver the activation energy required AND reclaim it back again.

The gyrotron remains on the surface and can generate a hole up to 100 times deeper than the beam width? A 20 kilometer hole would require a beam width of 200 meters? No. Will a drill pipe casing be needed to prevent collapse as already required for oil wells of much shallower depths and temperatures.

Waving hands, assuming a 20 kilometer well can be drilled and lined with unobtanium, what next? Pipe water down 20 kilometers to heat (supercritical at those conditions) and have the supercritical water raise to the surface to be used directly by a steam turbine? And what about the rate of thermal conduction through the rock to the well pipe? If the goal is to extract, say, 300-400 megawatts of thermal energy, would that not cool the surrounding rock to a temperature that would no longer be useful? Geothermal power plants in service today use either naturally occurring hot water or pump water down one will with recovery the heated water through another well. At 20 kilometers, one would doubt that the necessary fractured rock would occur naturally nor could be created or maintained by fracking.

This is one of those ridiculous projects that may be funded to make politicians look good and make universities happy with grant money. Everyone knows it’s a death-march project but who cares if it extracts money from the government?.

Who said anything about 20 km, that’s through hard rock. A simple microwave in your kitchen at low power will heat the ice enough to bore through it. This is ice we are talking about and the Gyrotron is an example of what can be done here on earth. The power levels would be minimal to bore through through the ice on Europa. You know you have a real negative attitude when you do not know what you are talking about. You need to read up on the subject.

My response was regarding the project to drill 20 km wells on earth to access geothermal energy as should be abundantly clear in my posting,

I will be happy to discuss technical matters with those qualified for such

I think their project sounds like a profitable endeavor … just not for geothermal power. A 100-to-1 hole will still look very impressive in a Russian tank, and a less powerful but well-collimated X-ray beam could make quite a dent in an independent journalism conference without raising so much as a trace of steam. Like Breakthrough Starshot, but formally aimed in the opposite direction.

I am sure that Russia have folks who feel the same way about the US. Both are wrong,

But back to a technical discussion. A probe using a heated fluid (via RTG or small fission reactor) would provide precise control over the temperature at the probe’s surface thereby provide control over the melting rate and minimizing energy consumption. The probe would need be have a density many times greater than water to exert a significant downward force. Ideally, the ice would simply be melted and then refreeze behind the probe. As suggested by many, a wire/fiber optics line would be unwound from the probe to maintain communications with the lander (20 km line would be quite a stretch – ha ha). Other mentioned the challenges of drifting ice breaking the connection.

It may be possible to steer the probe on a curved trajectory by applying more heat on one side than the other but that would only make sense if an unexpected resistance was encountered (rocky debris in the ice?). Fun to speculate.

“A 100-to-1 hole will still look very impressive in a Russian tank, and a less powerful but well-collimated X-ray beam could make quite a dent in an independent journalism conference without raising so much as a trace of steam.”

will probably leave some carbon, though …

First, I misspoke: this beam is millimeter waves, not X-rays.

@Michael Fidler – I think I share the skepticism about the likelihood of drilling to record depths, 20 km, under the arbitrarily chosen location of a coal power plant, using an untested method of drilling. Can you make a microwave beam that won’t spread out too far to be effective when beamed 20 km through vaporized rock?

Well actually it not a beam but like a drill bit but no bite just microwaves right against the rock, melting them. They are testing near where I use to live on the giant Newberry Volcano in central Oregon.

http://altarockenergy.com/

In the US, technology development at supercritical conditions is occurring at Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, Ozark Integrated Circuits, and Quaise Energy, all of whom AltaRock has partnered with. AltaRock funding helped get Quaise Energy started, and they are developing a directed energy drilling technology which can vaporize rock to enable very deep geothermal wells for a reasonable cost. This technology is critical to scaling SHR globally.

Here is an update, they use a waveguide to send it down.

High-power millimetre wave drilling for geothermal energy .

Granite, basalt, and limestone can be vaporized to over 3000 °C in a few minutes.

https://medium.com/age-of-awareness/high-power-millimetre-wave-drilling-for-geothermal-energy-66bd4b9f038f

I should of realized that since I work around radars and high frequencies communications in the Air Force and FAA. Yes, I can actually say I worked in a Microwave Range.

200kg? 12cm?

“We all need to be thinking bigger and better and really inspirationally about what we can do,” Matthews said. “Anyone who has worked on hardware design for space application knows you’re fighting for kilograms, and sometimes you’re fighting for grams, and that takes up so much time and energy. It really limits ultimately what your system can do. That’s gone away entirely.”

https://arstechnica.com/science/2022/05/spacex-engineer-says-nasa-should-plan-for-starships-significant-capability/

If it is some consolation, Europa’s surface gravity is about 13% of terrestrial (1.315 m/sec^2 vs. 9.8 ) and Enceladus an order of magnitude less ( 0.113 m/s² ). This might make penetration of a 25 kilometer ice shelf a little less daunting, but a preferred site would be where there is evidence of venting or discolorations from earlier leaks.

Additionally, with satellites embedded in magnetospheres, you have charged particles tied to rotating magnetic fields and then cycling in paths within them as well. Leeward and leading surface sites

might have different exposures to this bombardment. In effect, are the satellites whipped by more flux on forward surfaces or aft, north polar or south? In the case of Enceladus, disregarding magnetosphere flux, the obvious best site selection would be the south pole. But based on Saturn ( or Jupiter ) magnetospheric effects, would that come out as a preferred site selection?

The venting could be a problem since it may push VERNE back to the surface, it may need claws on it to hold it and push it down through the ice.

Hmmm….

Then venting could be a problem wherever this boring strategy is applied once a pressurized reservoir is reached.

Just for more background, assuming at Enceladus, water vapor is lofted to 50km and zero velocity, it escaped with a velocity of 100 m/sec. Some reports suggest much higher speeds ( 3 to 6 x faster). Yet 50 km is about 0.2 radii altitude. I suspect that individual vents range higher and lower than my estimate.

Reflecting on these circumstances, have to wonder if exploring the interior might take something like dropping a dense(r) instrument package from a blimp-like spacecraft buffeted by an upwelling stream.

The Starship is only slightly more real than the USS Enterprise on Star Trek, Starship even if successful, would require multiple in-orbit refueling, decades of development for such a journey and would be rendered useless by radiation long before reaching Europa. Let’s not put so much hope in another of Elon’s crazed ideas (partial list – hyperloop, battery-powered vertical take off supersonic passenger jets, tunnels under cities with 120 mph skateboards, neuralink, solar roof tops, etc.) that were either swindles or delusional. Tesla was stolen from the original designers and SpaceX was good but the claimed savings have yet to be realized (charging NASA $60 million per seat?). Placing bets on Starship would be a huge diversion of resources from more deserving projects.

Back on topic (sort of), a scientist proposed reaching the center of our moon by detonation of a series of nuclear bombs creating a rubble filled shaft to the center. Tunneling through the rubble would be comparatively easy The rubble eliminates the very high stress gradients at the wall that would otherwise causes tunnel collapse.

Not suggesting this approach for many reasons but there may still be odd solutions lurking out there,

Well, Musk has done an excellent job of making fools of the aerospace industries. Sending probes to the gas giants and their satellites that would be built by JPL and have a second stage designed for such flights is not decades off but a few years. Yes, Musk is an eccentric but a very smart eccentric and should be given due credit. All the great geniuses that where a head of their time where ridiculed and some even imprisoned by the ones in power. We should be happy we have someone that is capable enough to develop such advanced technologies. What should be worked on is the second stage that can send huge probes to the planets.

Musk’s teams of engineers and designers at Tesla and SpaceX have indeed done a good job. I will credit him with that. But his understanding of engineering design is tenuous although he is a skilled regurgitater of sciency sounding tidbits.

The chances of the above type of mission getting done in the next 25 to 50 years is likely close to zero and somewhere much closer to the StarShip Enterprise than StarShipElon succeeding to the fullest capability – in terms of getting a definitive answer. For me the minute you talk about RTG and potential search for life, then the conversation ends to a degree. Yes we have landed on Mars, where I would question its use, it was fairly clear that there was unlikely to be any life in the vicinity of the landing sites – if this was not clear, then its use was a irresponsible.

To fully explore, we need grander space faring capabilities. Whether that’s going to be via Elon, Jef or a GO is irrelevant. Carrying out these “nice” budget type of missions, where even upon the success of getting there, the likelihood of getting definitive answers will still be missing. We need to go there (with excessive resource) or concentrate on less “grand” and more “local” missions.

I agree with you on the RTG, no way to recover it, but hay the NAVY has dump tons of radioactive material off the coast of California from the nuclear test in the Marshall islands, but that’s another story. I’m sure the UES (Unidentified Exterrestrial Spacecraft) will not be happy with use dumping highly radioactive material material in Europa oceans…

This would be awesome! I can imagine how great a sensation it would be if we find animal life in planetary moon oceans. I can imagine the front cover of National Geographic graced with a photo of an extraterrestrial octopus. It is conceivable that any animal lifeforms in such environments may have developed technology.

I agree with you on the RTG, no way to recover it,

–> Thanks.

but hay the NAVY has dump tons of radioactive material off the coast of California from the nuclear test in the Marshall islands, but that’s another story.

–> Agreed, we don’t mind pooping in our own nest so we shouldn’t mind doing so in someone else’s!

I’m sure the UES (Unidentified Exterrestrial Spacecraft) will not be happy with use dumping highly radioactive material material in Europa oceans…

–> Well, if the UES’s let us know then I will have to eat my hat as the mission will have succeeded beyond my (or indeed anyone’s) wildest dreams!

Arthur C. Clark has some pretty wild dreams!

Europa.

https://2001.fandom.com/wiki/Europa

Excellent discussion and very close to my academic specialty – geothermal energy. I’ve talked with Quaise and Hypersciences and others doing innovative drilling – very promising, but still at low TRL – melt drilling looks most promising. I had really hoped the the Europa Clipper would have a melt drill, but no luck. If you can drill through a (relatively) thin part of the ice to get to the subsurface ocean, and if you can overcome all the engineering issues, you could likely generate a few Megawatts of electricity per well. Paper submitted to JBIS on the subject.

I had not thought of it in that form, as a power source on Europa, but it might work if the temperature of the ocean is high enough. The core may have a very high temperature but how to get the supercritical hot water to the surface?

Ocean Geothermal Energy Foundation.

Super Critical Water

Media

Professor Wilfred Elders explains super critical water and why it can make the power of a geothermal well 10x stronger. There are many favorable conditions for generating power in deep water on the mid ocean ridges. Most important is achieving super critical water. That is when the combination of high pressure (220 bars) and high heat (375c) make a fluid that is highly efficient at transferring heat to a turbine. Go to 5:20 in the video.

https://www.oceangeothermal.org/super-critical-water/

https://youtu.be/10DcCCLOMMg

Wow.

Well, good luck with this one. I won’t be holding my breath for the green light.

Enceladus’s oceans may be the right saltiness to sustain life

The geometry of the icy shell around Saturn’s moon Enceladus suggests that the ocean beneath is a little less salty than Earth’s oceans and could potentially sustain life.

SPACE 20 July 2022

By Karmela Padavic-Callaghan

The way ice covers the surface of Saturn’s moon Enceladus suggests that the oceans trapped beneath it may be only a little less salty than Earth’s oceans. The finding adds to the possibility that this moon might be able to sustain life.

The surface of Enceladus is encased in clean, bright ice. Wanying Kang at Massachusetts Institute of Technology and her colleagues wanted to determine what the characteristics of this ice shell indicate about the ocean beneath it.

Samples taken by the Cassini spacecraft of geyser-like jets of water from Enceladus’s surface previously showed that there is some organic matter that could sustain potential life on the icy moon. Considering the waters under Enceladus’s ice was the logical next step for inferring its habitability, says Kang.

The team devised a theoretical model detailing how ocean salinity, ocean currents and ice geometry affect each other on a planet or a moon, then tweaked it to best reproduce the properties of Enceladus’s ice.

Full article here…

https://www.newscientist.com/article/2329739-enceladuss-oceans-may-be-the-right-saltiness-to-sustain-life/

We need to explore the ice giants and their moons!

https://www.planetary.org/articles/nasa-mission-uranus-moons-ariel-miranda