Robert Gray was something of an outsider in the community of SETI scientists, spending most of his career in the world of big data, calculating mortgage lending patterns and examining issues in urban planning from his office in Chicago. As an independent consultant specializing in data analysis, his talents were widely deployed. But SETI was a passion more than a hobby for Gray, and he became highly regarded by scientists he worked with, many of whom were both surprised to hear of his death on December 6, 2021. It was Jim Benford who gave me the news just recently, and it humbles me to think that a Centauri Dreams post I worked with Gray to publish (How Far Can Civilization Go?) appeared just months before he died.

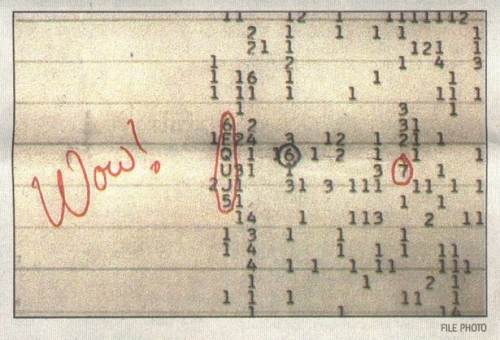

Gray’s independent status accounts for the lack of publicity about his death in our community, but I’m still startled that I’m only now learning about it. His name certainly has resonance on this site, particularly his book The Elusive Wow: Searching for Extraterrestrial Intelligence (Palmer Square Press, 2011), which should be on the bookshelf of anyone with a serious interest in SETI. The eponymous 1977 signal, received at Ohio State’s ‘Big Ear’ observatory, with Jerry Ehman’s enthusiastic ‘Wow!’ penciled in next to the printout, remains an enigma.

So obsessed was Gray with the signal – and with SETI investigation in general – that he built a radio telescope with a 12-foot dish in his backyard and pursued the work at professional installations like the Harvard/Smithsonian META radio telescope at Harvard’s Oak Ridge Observatory as well as the Very Large Array in New Mexico. He included Mount Pleasant Radio Observatory in Hobart, Tasmania in his world-spanning list of hunting grounds. His papers appeared in the likes of The Astrophysical Journal and Icarus; other essays went to such venues as Sky & Telescope, The Planetary Report, and Scientific American.

SETI has historically dealt in short ‘dwell’ times, meaning the observing instrument looks at a star and moves on so as to widen the search to as many stars as possible. Gray became interested in what would happen if we attempted long, fixed stares at high-interest stars, thus searching for signals that are intermittent as opposed to continuous. An interstellar beacon, whether targeted at specific stars or not, might send a signal that appeared and then disappeared for an arbitrary amount of time.

When I talked to Jim Benford about Gray’s work, he reminded me of his own prediction that the Wow Signal would never repeat. Interstellar applications of power beaming of the sort even now being investigated by Breakthrough Starshot would produce a small slew rate that would be consistent with a signal like the Wow as it moved across our sky. See Was the Wow Signal Due to Power Beaming Leakage for more, where Jim notes that:

The power beaming explanation for the Wow! accounts for all four of the Wow! parameters: the power density received, the duration of the signal, its frequency, and the reason why the Wow! has not occurred again. The Wow! power beam leakage hypothesis gets stronger the longer that listening for the Wow! to recur doesn’t observe it repeat.

Jim discussed power beaming as an option to explain the signal with Gray, who evidently found it one of several feasible explanations. When I first discussed it with Gray a few years back, he told me that a terrestrial explanation couldn’t be ruled out, but he found it hard to come up with a plausible one. On the phone with Jim Benford last night, I learned that Gray felt the signal was deeply enigmatic. The idea that we might never know what it was, as per Jim’s idea, would have deepened the mystery.

As to a terrestrial origin for the enigmatic reception, we would have to explain a signal that appeared at 1.42 GHz, while the band from 1.4 to 1.427 GHz is protected internationally – no emissions allowed. Aircraft can be ruled out because they would not remain static in the sky; moreover, the Ohio State observatory had excellent RFI rejection. You can see why the Wow! Signal retains its interest after all these years (see The Elusive Wow for much more). If power beaming is indeed in use in the galaxy, we may find SETI happening upon many such one-off signals as they sweep past, without serious hope of ever pinning them down to a definite source.

Power beaming aside, Gray was quite interested in intermittency as an antidote to the idea that we should look primarily for continuous isotropic broadcast signals. In a 2020 paper on the matter, he wrote:

…reducing the duty cycle to 1% could provide a 100-fold reduction in average power required, perhaps radiating for 1 s out of every 100 s. Searches observing targets for a matter of minutes might detect such signals, such as the Ohio State and META transit surveys which observed objects for 72 s and 120 s respectively, or Breakthrough Listen observing targets for three five minute periods…, or a targeted search such as Phoenix observing objects for 1,000 s in each of several spectral windows…, or the ATA observing for 30 minutes… Reducing duty cycle further yields further savings—for example a 10-4 duty cycle with a 104 reduction in average power might result in a 1 s signal every three hours, but most searches to date would be likely to miss such signals. Assuming longer signal duration does not help much; a 1-hour signal present every 100 or 10,000 hours would be very unlikely to be found by most current search strategies unless the population of such signals is large.

Gray had an excellent reputation among radio astronomers for the quality of his work; he was independent, disliked self-promotion (and particularly social media), and remained dogged in the pursuit of high-quality data. David Kipping (Columbia University), who worked with Gray on a recent paper in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, remembered him this way in an email this morning:

“I didn’t know Robert well, we only interacted virtually. I can say that I found his passion and persistence of the Wow signal to be an inspiration and reminded me that often the scientific investigative journey itself is the most valuable product of our endeavors. He’s an inspiration to amateur astronomers everywhere, a man who taught himself everything there was to know about that signal and more, and ended up using some of the largest radio telescopes in the world in pursuit of his dream. He was a gentleman to collaborate with and I only wish we’d had more time. It gives me a certain sense of satisfaction that his last paper with me demonstrated that for the Wow signal, hope still persists that it could repeat, not a lot of hope, but a little. And I think that’s a wonderful bookend to his publishing career.”

Beyond his work in SETI observations, Gray also looked at extending the familiar Kardashev scale, which ranks civilizations based on the energy they are able to use. In How Far Can Civilization Go?, which ran in these pages in 2021 and referenced an Astronomical Journal paper he had written on the subject, he noted that choosing what to look for in a SETI search depends on what we assume about the future course of a civilization and its power capabilities:

Whether any interstellar signals exist is unknown, and the question of how far civilization can go is critical in deciding what sort of signals to look for. If we think that civilizations can’t go hundreds or thousands of times further than our energy resources, then searches for broadcasts in all directions all of the time like many in progress might not succeed. But civilizations of roughly our level have plenty of power to signal by pointing a big antenna or telescope our way, although they might not revisit us very often, so we might need to find ways to listen to more of the sky more of the time.

I really admired the self-actualizing nature of Robert Gray’s scientific career. The man was a highly disciplined polymath whose academic background involved urban planning and policy, not physics, but without academic affiliation he made himself into a force in a highly specialized field and won the admiration of astronomers wherever he traveled. His papers are shrewd, thoughtful and provocative. I like what Jill Tarter told the Chicago Tribune shortly after his death. Calling Gray “larger than life,” Tarter added: “Bob was a constant. He really was intrigued and wanting to help, and he did — he actually followed through and was very forceful.”

Of the Gray papers I’ve mentioned above, his paper on SETI and intermittent reception is “Intermittent Signals and Planetary Days in SETI,” International Journal of Astrobiology 4 April 2020 (abstract). His paper on Kardashev is “The Extended Kardashev Scale,” Astronomical Journal 159, 228-232 (2020). Abstract. See also Kipping and Gray, “Could the ‘Wow’ signal have originated from a stochastic repeating beacon?” Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society Vol. 515, Issue 1 (September 2022), 1122-1129 (abstract).

I’ve always been troubled by the Wow! signal’s frequency, that of the interstellar hydrogen line. Sure, it is right in the Waterhole, an area of the microwave spectrum where there is little interference or noise from natural sources, but it is also at precisely a frequency where, at great distances, it could be lost in the ubiquitous 21-cm hiss of hydrogen gas in space. It can be argued that it is a frequency likely to be monitored by any civilization with astronomical interests, but transmitting at that precise frequency would mean the signal would be quickly overwhelmed by the roar from neutral hydrogen in the galactic disk. The Waterhole is deep, but there are narrowband spikes in it, mostly other atomic or molecular species found in the interstellar medium. Wouldn’t it make more sense to broadcast at some harmonic of the 21-cm line? Either double or half the frequency would be reasonable, or the frequency times a constant, like e or pi, and the signal would still be in the Waterhole where there is little noise to contend with.

If the signal is not a deliberate hail, but an accidentally intercepted by-product of some other industrial process (perhaps a navigational beacon, a planetary defense radar, or a local communications feed) then why transmit at such an iconic wavelength? What advantages would there be to utilize that wavelength for some routine purpose?

The fact that the signal was only observed briefly is of no particular significance, a beam of radio emission could sweep by the earth and be intercepted only briefly and probably never again, both transmitters and receivers are in constant motion and only an omnidirectional broadcast signal, or one carefully and deliberately aimed at the earth and tracking it, would likely stay put long enough to be detected more than once. Think of the flash of a lighthouse…the only reason ships can see it at great distances is that it is carefully aimed at the horizon, and that it repeats periodically.

Although the Wow! cannot be ruled out as being of interstellar origin, I believe it is most likely of human origin. It is either a hoax, an accidental transmission from some other nearby source or experiment, or a clandestine transmitter deliberating operating at a restricted frequency in order to avoid detection.

Coincidently, yesterday, the SETI Institute’s monthly online presentation was about the VLA and its real-time signal processing. The subject of the “Wow signal” was raised but dismissed as probably RFI.

Perhaps naively, it seems to me that local noise, even from satellites, could be eliminated by using 2 telescopes widely separated on Earth pointed in the same direction. Expensive perhaps especially if as large and complex as the VLA and their claim to be able to scan 40 million stars.

If transients are common, and perhaps the most likely state of ETI emissions, then we should use detection strategies that do not rely on serendipity. All-sky detection by 2 or more facilities, whether based on Earth, in Earth orbit, in radio-silent locations like lunar farside, and/or in deep space, might be the better solution to find transients and their patterns of transmission that would confirm that these are real, not RFI or natural phenomena, and then use directed search knowing when and where to look. Not an easy or cheap approach, but it might well test the hypothesis of ETI more thoroughly. As with SETI’s Hat Creek array, there is no need to make these dedicated SETI telescopes, but rather general survey ones that SETI piggybacks on.

Alex, as a start, we would have to know what terrestrial satellites were in range of Big Ear on August 15, 1977. We would also need to check if any military aircraft (or civilian ones for that matter) were flying over the area that day and trespassing into the radio Water Hole, but that might be even more difficult almost 46 years later. Did the Big Ear staff or anyone else take these into account at the time?

It really needs to be pointed out that the Big Ear SETI program consisted mainly of an automated search with data being printed out and having one or two technical folks check on it later – sometimes hours later. No immediate double checking and alerts to staff as would happen in modern times. I am not sure how much people appreciate that SETI in its early days was often sporadic and included token operations done largely by tenured astronomers in their off hours.

A few years back I read about even better candidate signals than the Wow but they never got the publicity that has turned the Wow! Signal into legendary status. I tried to find them again online but no luck so far. Does anyone happen to have information on these better candidates for potential ETI transmissions? One of the was detected from Australia for over one hour – compared to 72 seconds for the Wow! Signal of 1977.

FYI, I found this article from 2012 on Robert Gray and his search:

https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2012/02/the-wow-signal-one-mans-search-for-setis-most-tantalizing-trace-of-alien-life/253093/

Includes a link to this very relevant paper from January 10, 2001 on a VLA search for the Wow! Signal:

http://www.bigear.org/Gray-Marvel.pdf

Sad to hear about the loss of someone who made such contributions to the field – I clearly need to read his book on the WOW. I went to see what he’d written for SciAm and found, amusingly, an article on a subject I’m very fond of, the misinterpretation of the Fermi “Paradox”.

https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/guest-blog/the-fermi-paradox-is-not-fermi-s-and-it-is-not-a-paradox/

I argue against radio frequency interference (RFI) as a cause for the following reasons:

The Wow! Signal was at 1.42 GHz. the band from 1.4 to 1.427 GHz is protected internationally, meaning, as Kraus says, “all emissions are prohibited”. The band was set aside to allow radio astronomy of the H 1 line. Therefore it is very doubtful that the Wow! Was a transmission from Earth satellites or aircraft because they are forbidden to transmit in such bands. Secret satellites would avoid it because they would be detected by radio astronomers. (Emissions in this band are sometimes detected, but at very low levels. These are likely due to intermodulation products, which are nonlinear effects in electronics.)

Aircraft move in the sky, so would be unlikely to mimic that static signature; most spacecraft would pass through the beam much faster.

To match that motion, an Earth Satellite would have to be millions of kilometers distant, out far beyond the Moon.

The Big Ear had good RFI rejection because what was recorded was the difference between two offset beams, so a local signal appearing in both horns simultaneously would cancel. This was frequently verified.

The possibility that the Signal was a harmonic or sub-harmonic of a local signal is countered by Ohio State having monitored the 21 cm band for many years and presumably would have noticed a local interfering signal.

A deliberate hoax? This lacks credibility, as hoaxes are a practical joke, which succeed if they are later revealed. Then why keep it secret for decades?

Why not unshielded equipment emissions or even a cosmic FRB emission? RFI is not only from ordered transmissions. Computers are supposed to be shielded to prevent emissions, and who can forget the radio interference from electric shavers (showing my age)? I am sure that there are good reasons to eliminate electrical and electronic equipment RFI, but FRBs weren’t even known in 1979.

Now, this star:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2MASS_19281982-2640123

Was near the signal location—now, I cannot help but wonder if Earth passed through its Focal Line, and we heard some type of catastrophe on the other side of it?

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sagittarius_A

In 1977, 1.42GHz was not a frequency easily achievable at the time with readily available equipment. It is highly unlikely some ordinary industrial or hobbyist gear could have been emitting at that frequency. It had to be on purpose! Neither is it a wavelength common to any natural processes (except, of course, the quantum spin flip of the monoatomic hydrogen electron).

I don’t know much about electronics, but I suppose its possible that some military radar operated at that frequency, or used oscillators in superheterodyne electronics that might have emitted a leaked signal that the telescope accidentally picked up. Radio astronomy receivers are extremely sensitive.

As for it being a “forbidden freq”, I remember in a conversation with Charles Seeger that he could recall several instances in which radio astronomers had to call up government spies and scold them for emitting at frequencies reserved for scientific use.. The spooks invariably claimed they were not at fault, but soon after they were warned the outlaw transmissions always stopped.

The only other possibility was that it was a transient formed by an alien, directional signal that just happened to accidentally intersect our solar system on its way to somewhere else. All the stars nearby to Sol have proper motions relative to our system on the order of 10 to 100 km/sec. This is also on the order of our own orbital velocity about the sun. If the beam was narrow enough, it is not unreasonable to assume the earth was illuminated only once. I suspect the brief (72s) appearance of the Wow! was caused by the Earth’s rotation, At any rate, by the time the Earth (and the Big Ear) rotated for a full 24 hours, we were no longer in the beam. We will never hear it again.

Robert was an inspiration to those of us who are, for lack of a better description, ‘educated laymen’ who are interested/fascinated in fields that are not part of our formal education.

Is it possible that transient radio signals might be gravitationally lensed images of distant objects focused temporarily on our solar system by some intervening mass?

I suspect gravitational lensing is frequency-dependent, so the fact that the Wow! signal was precisely at a well-studied spike in the radio spectrum is really stretching coincidence, but stranger things have been know to happen. Consider, a distant, monoatomic hydrogen-rich galaxy or other nebular H1 concentration is gravitationally lensed by a planet, or black hole or some other mass between us and it.. All the other frequencies are unfocussed and invisible but by luck, we are at the precise spot where the 1.4 GHz radiation form the lensed H1 is focused. Actually, at such a long wavelength (compared to optical frequencies) that’ precise spot” might spatially, be quite large and spread out, spatially. All the other EM frequencies refracted by the Einstein Lens would be totally out of focus, and unobservable.

The lensing spacing would be so geometrically critical that the slightest movement over a sidereal day would be enough to alter the alignment and the signal would vanish forever.

Yeah, I know its a long shot, but it can’t be ruled out, eh?

Does the “focus” just need to be a stronger signal than the background h2 emissions? The source could just be any reasonable H2 emission which is then focused to increase the signal strength as you suggest. What is the probability that the Earth has crossed that focused (or at least strengthened) signal? Is it very low or could it be much higher than intuition might suggest?

I’m afraid I’m not qualified to answer your questions. I am not an astronomer or a physicist, just an enthusiastic amateur. But you have raised valid points.

As we pass through a lensing event we would see an increase in signal before the main ring event and then a decrease in signal after it. The increase and decrease part would not be as bright as the ring but I would have thought over 24hr we would still have seen the signal.

https://www.wikiwand.com/en/Strong_gravitational_lensing#Media/File:Imageedit_6_2578820362.gif

Most of the lensing events I’m familiar with are of distant galaxies refracting the light of even more distant galaxies. The angular motions of these objects relative to one another are probably insignificant. That is, if we see a lensing event of an object many megaparsecs away, it is not likely to be gone if we look for it again tomorrow.

On the other hand, the lensing geometry of an object in our own galaxy by the mass of an even nearer gravitational lens may be much more a function of time. The motion of the sun around the galactic center, as well as its own motion relative to the LSR, might alter the geometry over relatively short periods of time, causing a gravitationally lensed image to be a temporary phenomenon. The earth-sun system, the lensing body, and the lensed object are all in motion relative to one another. It is not inconceivable that such an observation might be a short term phenomenon.

In the case of the Wow signal, or other radio transients, when viewed by a fixed antenna array like the Ohio State Big Ear, you also have to factor in the rotation of the earth into the equation. If the focusing object is relatively nearby and exhibits a large radial velocity and proper motion, the geometry of the lensed event may change rather quickly.

A I pointed out to Mr Tolley above, I am not technically qualified to do a rigorous analysis of the phenomenon, Hopefully, one of our readers is. The question may be phrased more precisely thusly:

“Are there combinations of lensing geometries and proper motions involving the object, the mass, and the earth that could produce a radio transient like the Wow signal?”

Secondly,

“Is it likely that these conditions, if they exist, are likely to produce additional transients at a frequency high enough to make it worthwhile to search for them?

Hopefully, a deep understanding of this type of phenomenon may establish criteria by which these events can be identified and the phenomena eliminated as possible ETI activity.

If we use our sun’s focal line as a model, then, IIRC, it starts around 550 AU, but loses effectiveness after 1000 AU. Planets have far longer starting focal points as their gravitational bending of light is weaker.

To get a transient signal seems to imply an object that moves against the sky, which implies a body relatively near to us so that the focal line will intersect the Earth but be lost as it moves in the sky. A black hole might work but it would have to be very close by. A dim star that has not shown up in the IR might work, or a rogue planet. Given the recent post by Andreas Hein on probes to 1000 AU and the ubiquity of different-sized celestial bodies, just possibly a Jupiter-plus-sized body might be out there and could fit the bill, unseen, but with a focal line that might well mimic a transient.

Just a thought since you raised the possibility..

“when viewed by a fixed antenna array like the Ohio State Big Ear, you also have to factor in the rotation of the earth into the equation”

I won’t attempt a general solution, however I am certain that it’s all laid out in the abundance of analyses that have accumulated over the decades. I’ll describe one simple aspect since it may be helpful.

Earth rotates 1 degree every 4 minutes. The length of the described arc is proportional to the cosine of the celestial latitude as seen from Earth’s surface. That is, a degree of celestial longitude gets shorter as approach the celestial poles, and is 0 at the poles (e.g. Polaris has an almost fixed position).

The beam width of the antenna is always known and varies with frequency (up to a maximum frequency where the geometry errors are more than about 1/8 of a wavelength).

Put those two factors together and you can calculate how long a signal at a given celestial position (where the antenna was pointed when the Wow! occurred) will appear at the receiver. I’m simplifying quite a lot.

I think you’ll find that pretty well any cosmological lensing event lasts far longer than it takes the beam to sweep past it. It’ll almost certain to be there the next day or even far longer. If the source is closer, moving, or of technical origin, and depending on the apparent diameter of the source, the reception window could fall anywhere in a range of a fraction of a second to days.

Further, duration of the signal is a factor. A technological signal could be only briefly transmitted or transmitted in our direction. Astronomical signals are usually of long duration except for particularly violent events like an object hitting or being disrupted by a high mass compact object, stellar flare, etc.

To the extent that Gray was inspired by the “Wow” signal to get involved, well that’s good. I only hope that he was never so fixated on it that it derailed him from more productive paths. I know nothing about him so I can’t say.

Every idea of what the signal might have been is at best a hypothesis. Sometimes reasonable and sometimes exceedingly wild. Numerous hypotheses have been tested to the extent possible, and have hit a brick wall. It is not valid to claim that any of these are more than hypotheses. There is no data to say anything more, and we are unlikely, after many decades, to ever be able to say more.

An unknown is an unknown. Frustrating but that’s how it is. Further hypothesis generation is speculation that can lead to interesting conversations or discussion, and nothing more.

A quote by Paul of Jim Benford is noteworthy: “The Wow! power beam leakage hypothesis gets stronger the longer that listening for the Wow! to recur doesn’t observe it repeat.”

No, that not a valid analysis. The hypothesis is weak and remains weak, and that will be true no matter how much time passes. To claim otherwise is to claim knowledge of the prior probabilities for all possible hypotheses, and that is far from the case.

Definitely fascinating! We have something that is hard to explain as non-technological. This can spur us on to search for other similar signals.

Perhaps there is a universal order of RF communicating civilizations.

If quantum teleportation of large craft can be figured out, then at least we have light-speed as perhaps effectively enabled. Perhaps the teleportation mediation can be a very short and powerful pulse of RF while the classical feedback loop can be a similar pulse.

Definitely fun stuff to ponder.

The “Wow” signal is what “Contact” and the “Star Trek Universe” were all about. Drake and Sagan thought the radio telescopes would be filled with the galactic chatter of many advanced civilizations! Very exciting times.

Unfortunately, silence is the truth, and even hard core SciFi lovers like me now have trouble watching the Star Trek Universe with humanoid aliens all around.

The perspective we grew up with was from Kepler. We occupy no special place in the galaxy and are far from the center, circling an “average” mundane star. So reasonable thinkers concluded that life must be “everywhere” and abundant! Gosh it’s hard to let go of that. But now the “Rare Earth” theory has gained prominence, and we also find that the sun “is not a Sun-like” star! It’s very stable and quiet.

Once again, for better or worse, we are very, very special. And alone.

You may very well be right. But I prefer to believe intelligent, technical, long-lived species are not impossible, just extremely rare and highly separated in space and time. We will probably never stumble across another one.

But I’m not sure I want to live in a universe where we are totally alone. If we’re the best God can do, then the Universe is a failed experiment.

The ubiquity and type of life seem to swing back and forth like a pendulum. Once it was thought that every celestial body was inhabited, even the sun. The Bat People Moon hoax was perpetrated 1n 1835, less than 2 centuries ago. Lowell was talking up Martians in the last century. The various space probes and landers on Mars seemed to have dimmed hopes, and The Rare Earth Hypothesis, plus the possibly the Fermi Question seems to have quashed hopes for ETI (but not unicellular life). Even the UFO craze seemed to subside somewhat. Then, for whatever reason, Nasa’s “follow the water” mantra plus new hypotheses concerning abiogenesis seems to have raised hopes that at least life is common, even if principally unicellular. It certainly has helped those now suggesting life in the subsurface oceans of icy worlds. But post Star Wars (1977) there have been many more Sci-Fi tv shows and movies, and aliens, usually depicted as humanoid, seem to have revived the bipedal ETI meme. Gould was one biologist who thought that if we could rewind evolution on Earth that we would end up with very different life forms, [and humans would be a very low probability event?] due to evolution being a contingent process. What we do see in evolution as each new major type emerges is increasing brain-to-body mass ratios suggesting that intelligence is a useful survival trick. Whether human-level intelligence is a survival trait remains to be seen. Like extreme body size, there may be limits to its value.

What is exciting is that we may be on the cusp of getting data on exoplanet biosignatures that will help decide the question of life being ubiquitous or not. It could go either way, a universe full of life, or a sterile one. Hopefully, it doesn’t prove as misleading as Lowell’s Martian canals. A successful technosignature detection would help to resolve the question of whether technological life emerges and is extant.

Either outcome should have profound implications. OTOH, if life appears rarely, with most planets being sterile, it will raise the question of whether we should “green” those sterile worlds when the capability arises.

I would disagree Paul Wilson. Your hypothesis is that we are very, very special and alone, but we don’t have anywhere near enough data to support that view. We haven’t looked very hard and we haven’t looked for very long. We could still be surrounded by other sentient organisms in other star systems within the galaxy who know nothing about RF transmissions, or gravitational lensing, or searching for other sentient species on other planets or interstellar travel. In a few hundred years we may know that there are no ETI within some constrained volume of space around our solar system such as a 100 light year “bubble”. But as of now we know almost nothing. It’s important to realize how in the dark we really are.

I understand and do not really disagree with you.

The fly in the ointment is the Fermi Paradox. If we are not very special and life, including intelligent life abounds in the galaxy (let alone the universe) then one of those civilizations should have broken out and established itself in space. They should have been able to come to Earth and long ago. They are not here, and with no sign that they were ever here, and no chatter from the galaxy, it’s silent and sobering.

Imo, Robert Gray was too optimistic about the Wow! signal but very reasonable in his criticism of Tipping’s and Hart’s approach to the Fermi question. I would be less gentlemanly than Gray and describe their approach, and the general assumption that there is a paradox, as inherently dishonest. A galactic reach is not equivalent to colonizing every star system. The carrying capacity of an environment is completely dependent on a people’s or specie’s lifestyle. To be a paradox, the Fermi question must assume a narrow band of lifestyles. Tipping’s and Hart’s premise insists that the only lifestyle available to a space faring people after leaving their home world is grabby. This is an absurd assumption.

If there are lots of civilizations out there, then you have to explain why they all chose to be non-grabby.

There are so many “explanations” of why aliens seem to be absent (as well as those who suggest we are blind because they are in our skies, and also abducting people).

I wouldn’t call their hypothesis dishonest, although it might say a lot about Proxmire and other legislators who supposedly used their testimony to defund SETI. We’ve seen how stupid some legislators can be with regard to Covid public health management and the use of bogus treatments vs vaccines. Are “high public debt is a disaster for the USA” Cassandras also dishonest [as well as a host of other economic myths expounded]?

Rather than making definitive statements, we should accept our current ignorance and keep trying to detect ETI[s]. If humanity is still around in a million years with vastly superior technology, even interstellar travel, we should have an answer by then, either way.

Unicorns are a conceptually perfect animal, they can’t be excluded from the probability space for Earth life. However, they are nowhere to be found and their absence can be explained by the very same theory that provides for their conceptualization. Same applies to grabby aliens. Grabby describes a larger set of traits beyond leaving their home world.

Economics, especially the Chicago school, is plagued by physics envy, the desire to reduce their field to perfect theories. Friedman’s theory for inflation doesn’t explain how money realistically is created (through lending) and is dishonestly described as economic law.

Tipping and Hart’s premise is similar physics envy. I would describe any theory that camouflages its assumptions as dishonest and their premise requires the assumption that leaving your homeworld is equivalent to colonizing every star system. Their space faring people are just a mathematical reduction. SETI is a soft science and the Fermi question can only be answered by searching.

regarding unicorns. You may recall that once it was believed all swans were white. It was only when Europeans reached Australia that black swans were found. My point is that we can never prove negatives. Unicorns don’t exist on Earth, although someone may gene engineer one in the future, they may exist elsewhere or elsewhen.

Not sure how Friedman’s theory of money supply and inflation entered into this discussion, but I think saying it is called a law is a strawman argument. A Google search confirms my recollection that it was called a rule. IMO, Keynesian economics is still the better explanation and there is no law in any of his theories, afaik.

I don’t disagree with you that the Tipler-Hart explanation is nothing more than another speculation, but whether it has anything to do with physics envy or dishonesty in the way it was promoted, I don’t have any opinion on that. Yes, they used Fermi’s name to fallaciously argue from authority. Yes, legislators, especially the grandstanding, agendared Proxmire used that as an excuse to defund SETI. Was it dishonesty or just a successfully promoted viewpoint that made the decision easier for him?

Absolutely agree. The only arguments should be over what methods to use.

The “first means only” premise doesn’t theorize that a collection of traits, unicorn, black swan or grabby alien, may exist but that all life must, everywhere and everywhen, contain that collection of traits. You are using the possibility of grabby aliens as a defense for a theory that states only grabby aliens can exist. It doesn’t work. The potential for variation is diametrically opposed to the premise that variation is impossible.

I do not know much about Hart, but Tipler’s ideas have long since gone off the rails into pseudoscience:

http://web.archive.org/web/20090106004121/www.geocities.com/theophysics/

I know that no small part of why we haven’t found ETI yet is because those in authority, when they either do not think about the concept or just dismiss it outright due to limited cultural thinking, fear the idea of more powerful beings who could descend upon us and remove them from their self-appointed thrones. That they might also take out all of humanity is only of concern to them that they then lose subjects to manipulate.

An interesting read. Tipler’s reasoning was sound, though it rested on a rickety basis. The black hole information paradox seemed insoluble (compare https://physics.mit.edu/

news/has-the-black-hole-information-paradox-evaporated/ ), and I think a closed universe, though deemed improbable even then, was not as well excluded. And when physicists start talking about life in the latter days of a closed universe, they all start sounding like that. The most doubtful of Tipler’s assumptions is that human consciousness can be coded into arbitrarily small regions of semiconductor, and improved without limit; but that is widely believed to this day.

Feynmann was the first, I think, to suggest that there was a long way to go in terms of increasing information density. While more like static RAM media, synthetic DNA has been used to store information and using isotopic carbon could increase the storage of a bit to the single-atom level. Reading this data is another issue.

I don’t know about “improving human consciousness without limit”. Without limit suggests god-like consciousness, and so far our religious texts don’t suggest this would be a “good thing” for non-god-like people. Is this really “widely believed” today?

It would be interesting to do a thought experiment where we have developed a drive capable of achieving speeds near the light limit, then go on a multi-year voyage to a relatively nearby star and then head back home. I’m not sure what the time dilation factor would be but let’s assume hundreds of years had passed on Earth. Upon return would we find a vibrant human civilization which had come to terms with living in harmony with Nature or would we be effectively extinct due to our destructive tendencies? If the former possibility prevailed I think we would have discovered numerous worlds with at least some type of life, and very rarely some form of sentience. There are obviously some interesting features about the Earth such as a large moon, tectonic activity, a strong magnetosphere etc., but I believe life can arise under many varied conditions if certain compounds and energy sources are available (and vast amounts of time of course). A sterile universe with the exception of the Earth does not seem likely at all. The Fermi paradox just isn’t relevant. Time and data collection are.

Earth life lives in “harmony” with Earth life and all life on Earth will spread to fill their current niche or evolve to fully inhabit a new niche. Living in “harmony” or “harmonic fitness” with an environment does not preclude expanding to fully inhabit a space.

When you offer that space faring people may never leave their homeworld as a reaction to the “first and only” premise you are validating the dysfunctional equivalency of expansion and footprint that the theory insists must be true. A better reaction is to point to the probability space describing all possible space faring lifestyles. It is impossible to regard that space and consider the ‘first and only” premise as a coherent answer to the Fermi question.

It is always inspiring to look back at the first pioneers of a field. Still, I hope that practical SETI will keep looking forward to new possibilities. You could detect radio waves in 1977, but now you can detect gravity waves also (to some extent). I just saw a paper about trying to detect “dark photons” that might be produced by gravitational interactions, which I imagine might fly straight through dust and gas, and each of which apparently would carry an intrinsic “rest energy” that sounds like it might be a frame-independent way to code information. https://arxiv.org/pdf/2208.06519.pdf Even if our correspondents are using plain EM, maybe they send up a weak coherent signal lost in the noise, and expect us to reflect and collect that light perfectly out of the noise with an “anti-laser”. https://phys.org/news/2023-01-anti-laser-device.html

The aliens (if any) are ahead of us. Maybe they even think it is unethical to communicate with too primitive a civilization. So SETI needs people working at every forefront of physics to find new ways to listen for them.

Now this will be a huge step towards Radio SETI, not to mention Radio Astronomy.

Finally someone is actually doing something in this area rather than writing yet another white paper on the subject!

https://www.universetoday.com/159803/astronomers-prepare-lusee-a-test-observatory-for-the-far-side-of-the-moon/

Yuri Milner’s Breakthrough Listen Joins the MeerKAT Observatory in the Hunt for Extraterrestrial Intelligence

Posted by Craig Zedwick

January 30, 2023

An astronomical program led by Yuri Milner is hoping to detect signals from alien civilizations, so they have teamed up with a giant radio telescope in the Southern Hemisphere. The MeerKAT Observatory, situated in a remote region of South Africa, is set to help Breakthrough Listen further the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence (SETI).

Listen is one of five Breakthrough Initiatives and space science projects from billionaire philanthropist Yuri Milner. A significant component of his Giving Pledge work, the Breakthrough Initiatives seek answers to the Universe’s most profound questions, such as “are we alone?” This, and other cosmic conundrums, are also the subject of Yuri Milner’s book Eureka Manifesto.

Full article here:

https://nerdsmagazine.com/yuri-milner-joins-meerkat-to-search-for-alien-life/

Download Yuri Milner’s book Eureka Manifesto here:

https://yurimilnermanifesto.org/

A NEW ERA OF OPTICAL SETI: THE SEARCH FOR ARTIFICIAL OBJECTS OF NON-HUMAN ORIGIN

BEATRIZ VILLARROEL AND GEOFF MARCY

FEBRUARY 20, 2023

https://thedebrief.org/a-new-era-of-optical-seti-the-search-for-artificial-objects-of-non-human-origin/