The problem with Alpha Centauri is that the system is too close. I don’t refer to its 4.3 light year distance from Sol, which makes these stars targets for future interstellar probes, but rather the distance of the two primary stars, Centauri A and B, from each other. The G-class Centauri A and K-class Centauri B orbit a common barycenter that takes them from a maximum of 35.6 AU to 11.2 AU during the roughly 80 year orbital period. That puts their average distance from each other at 23 AU.

So the average orbital distance here is a bit further than Uranus’ orbit of the Sun, while the closest approach takes the two stars almost as close as the Sun and Saturn. Habitable zone orbits are possible around both stars, making for interesting scenarios indeed, but finding out just how the system is populated with planets is not easy. We’ve learned a great deal about Proxima Centauri’s planets, but teasing out a planetary signature from our data on Centauri A and B has been frustrating despite many attempts. Alpha Centauri Bb, announced in 2012, is no longer considered a valid detection.

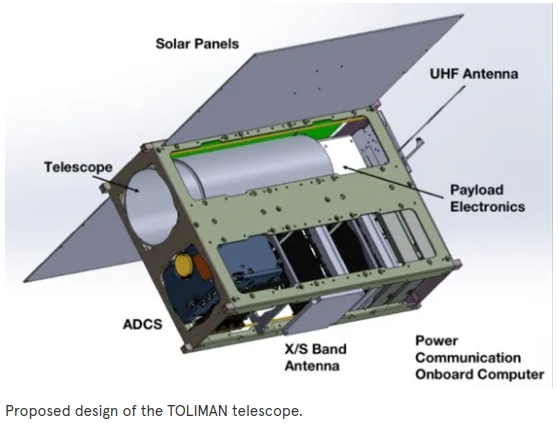

But the work continues. I was pleased to see just the other day that Peter Tuthill (University of Sydney) is continuing to advance a mission called TOLIMAN, which we’ve discussed in earlier articles (citations below). The acronym here stands for Telescope for Orbit Locus Interferometric Monitoring of our Astronomical Neighborhood, a mission designed around astrometry and a small 30cm narrow-field telescope. The project has signed a contract with Sofia-based satellite and space services company EnduroSat, whose MicroSat technology can downlink data at 125+ Mbps, and if the mission goes as planned, there will be data aplenty.

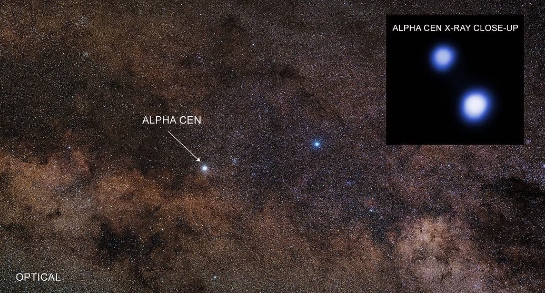

Image: Alpha Centauri is our nearest star system, best known in the Southern Hemisphere as the bottom of the two pointers to the Southern Cross. The stars are seen here in optical and x-ray spectra. Source: NASA.

The technology here is quite interesting, and a departure from other astrometry missions. Astrometry is all about tracking the minute changes in the position of stars as they are affected by the gravitational pull of planets orbiting them, a series of angular displacements that can result in calculations of the planet’s mass and orbit. Whereas both transit and radial velocity methods work best when dealing with planets close to their star, astrometry is the reverse, becoming more effective with separation.

Finding an Earth-class planet in the habitable zone around one of these two stars requires us to identify a signal in the range of 2.5 micro-arcseconds for Centauri A, an amount that is halved for a planet around Centauri B. Not an easy catch, but the ingenious TOLIMAN technology uses a ‘diffractive pupil’ to spread the starlight and increase the ability to spot and subtract systematic errors. I’ve quoted the team’s online description before but it usefully encapsulates the method, which has no need of field stars as references because it uses the binary companion to the star being examined as a reference, making a small aperture suitable for the work.

With the fortuitous presence of a bright phase reference only arcseconds away, measurements are immediately 2 – 3 orders of magnitude more precise than for a randomly chosen bright field star where many-arcminute fields (or larger) are required to find background stars for this task. Maintaining the instrument imaging distortions stable over a few arcseconds is considerably easier than requiring similar stability over arcminutes or degrees. Alpha Cen’s proximity to Earth means that the angular deviations on the sky are proportionately larger (typically a factor of ~10-100 compared to a population of comparably bright stars).

Image: Telescope design: The proposed TOLIMAN space telescope with a candidate telescope mirror pattern known as a diffractive pupil. Rather than concentrating the starlight into a tight focused beam as is usually done for optical systems, TOLIMAN has a strongly featured pattern, spreading starlight into a complex flower pattern that, paradoxically, makes it easier to register the fine detail required in the measurement to detect the small wobbles a planet would make in the star’s motion. Credit: Peter Tuthill / University of Sydney.

You can imagine the thermal and mechanical stability issues involved here. Doubtless Tuthill’s experience in the design of NIRISS (Near-Infrared Imager and Slitless Spectrograph ) and the aperture masking interferometry for the instrument on the James Webb Space Telescope will inform the evolution of the TOLIMAN hardware. As to EnduroSat, Raycho Raychev, founder and CEO, has this to say:

“We are exceptionally proud to partner in this mission. The challenges are enormous, and it will drive our engineering efforts to the extreme. The mission is a first-of-its-kind exploration science effort and will help open the doors for low-cost astronomy missions.”

A successful TOLIMAN mission could lead to what the team has referred to as TOLIMAN+, a larger instrument capable of detecting Earth-class worlds around both 61 Cygni and 70 Ophiuchi. But let’s get the Alpha Centauri results first, perhaps leading to detections around a target whose planetary signals would be much stronger than those of these other systems. We’ve seen how larger instruments like those aboard HIPPARCOS and Gaia have used astrometry to upgrade our view of vast numbers of stars, but it may be a small, dedicated mission with a unique technology that finally settles the question of planets around the two nearest Sun-like stars.

For more on TOLIMAN, see two previous posts: TOLIMAN Targets Centauri A/B Planets and TOLIMAN: Looking for Earth Mass Planets at Alpha Centauri. Also see this useful backgrounder.

2-3 orders of magnitude seem like a huge “free” benefit in astrometry for binary stars. Is this improvement in precision and accuracy a general case? I assume it is given the suggestion that a larger telescope could do the same work around the binaries 61 Cygni and 70 Ophiuchi. If so, just what would the limits of different-sized space telescopes be for binary stars to detect various-sized worlds from brown dwarfs, Super-Jupiters, and down to Mars-sized worlds? Is there a formula to estimate this?

It’s hard to tell without something to give the scale but….are they planning to build this based on a standard computer case? That would be a heck of an accomplished use of off-the-shelf components! I skimmed the “backgrounder” but didn’t see any details of the design.

Thanks ! Just yesterday I was looking for an update on Toliman!

If I understand this (?), the TOLIMAN mission would detect a second order effect on the astrometric behavior of one or the other of the Alpha Centauri stars. And the happiest result would be detections of terrestrial planets in the HZ of each. For the A component and an “Earth”, the mass ratio would be akin to ours about 330,000 to one, A’s favor. But then, after that, the period of this phenomenon would be related to the period of the planet. My old studies had a baseline case of about 484 days. The binary system is about 79.92 years. So in this case there were dozens of low amplitude oscillations per binary period – in principle. The B case, would be based on period around 204 days.

Both these baselines were calculated with local equilibrium temperatures ( Stefan Boltzmann BB luminosity temperatures) stellar surface temperatures to 400 K locally. Add or subtract 25 or 50 K and then you are moving in a band around the terrestrial (1 AU) reference.

So, I supppose that if you had terrestrial planets in both systems, you would have overlays on those astrometric signals of different frequencies. Then, of course, if the systems have more than one planet, each, there would be more. Plus, Alpha Centauri system is eccentric, e ~ 0.52. So, if this works, and there are a lot of planets, then the signal extracted could be quite complex, if detectable above noise. And then, noise might look a lot like a horn of plenty full of various planets.

Very good video of Professor Tuthill explaining the surprising developments of the “diffractive pupil” for the TOLIMAN space telescope in relatively easy layman terms.

Habitable Zone Earth Analog Planets with the TOLIMAN Space Telescope.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=933auQYMqSM

Good article.

Journal of the Optical Society of America B.

Phase retrieval and design with automatic differentiation.

https://opg.optica.org/josab/fulltext.cfm?uri=josab-38-9-2465&id=455983

“By exploiting newly efficient and flexible technology for automatic differentiation, which in recent years has undergone rapid development driven by machine learning (AI), we can perform both phase retrieval and design in a way that is systematic, user-friendly, fast, and effective.

By using modern gradient descent techniques, this converges efficiently and is easily extended to incorporate constraints and regularization. We illustrate the wide-ranging potential for this approach using our new package, Morphine. Challenging applications performed with this code

include precise phase retrieval for both discrete and continuous phase distributions, even where information has been censored such as heavily-saturated sensor data. We also show that the same algorithms can optimize continuous or binary phase masks that are competitive with existing best solutions for two example problems: an Apodizing Phase Plate (APP) coronagraph for exoplanet direct imaging, and a diffractive pupil for narrow-angle astrometry”

This is the other area that is fast becoming practical from this research: Direct imaging of Exoplanets.

Another article detailing this with Professor Tuthill:

Building hybridized 28-baseline pupil-remapping photonic interferometers for future high-resolution imaging.

https://opg.optica.org/ao/abstract.cfm?uri=ao-60-19-D33

“The detection and the characterization of exoplanets close to their host star, and particularly within the habitable zone, is one of the most pressing instrumental challenges faced by contemporary astronomy. Such detections require a high angular resolution and ability to handle a high planet-to-star contrast ratio, the latter ranging from 10?4, for self luminous hot exoplanets observed in the mid-infrared to 10?10, for Earth-like exoplanets imaged in reflected light from their host star Schworer and Tuthill [2015]. Nulling interferometry fulfills both requirements by making an on-axis source (the star) destructively interfere while transmitting the light from an off-axis companion (a

planet).

The backgrounder section above provides some interesting background, of course, but it also raises more questions. It would appear that procedure fixes on star A or B and examines its motion with respect to background galactic stars. If there are perturbations, I presume, during a campaign of unspecified time, that would be evidence of other acting bodies, and that in the case of “A”, “B” would be less of a perturber than a local HZ Earth. And interesting argument.

On the other hand, we do know that Alpha Cen A and B are rotating around a center of mass in elliptic orbits. Our estimates of their mass are based on a ratio of mass and perceived separation. These are easier to establish than a planetary perturber in this case, and we should have some data bases for that. The most recent I can find are updates to original Hipparcos measures. There might be Gaia data, but I am yet to find them. Given that we have Gaia data, and assuming the two principal masses are known to have orbital elements to some level of determination as a result, departures from the elliptic traces of one or the other star against a Gaia catalog background would be what I would think would be the detection of a planet’s presence. Amplitude and period would determine the mass and radial distance from the star.

There might be arguments pro and con for which one gives you the lower arc-second fraction threshold, but I suspect that it is the one that I just described. And that you would need a couple of local years or planetary orbits to extract the data. And then that the table would be turning due to the primary bodies’ changing angular rates.

But at the very least, I wish I knew what the Gaia best estimates were for the Alpha Centauri system orbital elements and derived masses.

Including the error bars.

An essential mission

In an earlier note above, I mentioned an estimated orbital radius for an Earth analog at A with a semi-major axis of about 1.246 AU and a consequent period 484 days, based on data available when I had initiated the study and was still carrying in the late 90s. It seemed to serve well enough for the issue of dynamic stability and for comparison with other local stars known to about the same decimal accuracy.

Well, times have changed. We do have more accurate measures of the local stars, we know that there are exoplanets and we are busy trying to detect them.

The specific parameters of the Alpha Centauri system have been refined over decades – and since successful location or spotting ( at least astrometric) of planets is so dependent on their precise definition in the celestial sphere, it sent me searching for the latest updates. At first I thought they would be the result of Gaia results, but I believe that the short answer is either “no” or “not yet”. Gaia has data based on precise fixes of Alpha Centauri, but the data reduction, as far as I can tell thus far, has not been published. There is evidently a lag time for such products. However, the most recent material I have been able to find based on ALMA ( and Hipparcos) is worth examining:

Precision Millimeter Astrometry of the Alpha Centauri AB System

Rachel Akeson et al.

The Astronomical Journal, 162:24 (19 page) July, 2021.

https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.3847/1538-3881/abfaff

Abstract: … Here we describe initial results from an Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) program to search for planets in the Alpha Centauri system using differential astrometry at millimeter wavelengts of the proper motion, orbital motion and parallax of the Alpha Cen system. …Our estimeate of ALMA’s relative astrometric precision suggest we will ultimately be sensitive to planets of a few tens of Earth mass in orbits from 1 to 3 au where stable orbits are thought to exist.

====

In this report, with the corresponding Earth analog, the reference semi major axis somewhat narrower ( a = 1.2) and with a consequent shorter period. Fortunately, the paper derives just about any orbital element or celestial position parameter to high accuracy. Also some comparisons with some earlier estimates. And I should note, that since the time I gathered my database for stability analyses, Alpha Centauri’s did not stay static.

Here are some I’d like to point out:

ALMA 1985

a (arc seconds) 17.4930 +/-0.0097

P (year) 79.2430 79.92

mA 1.0788+/-0.0089 1.1

mB 0.9092+/-0.0025 0.85

mA/(mA+mB) 0.54266+/- 0.00011

e 0.519471 +/- 0.015 0.52

LA 1.2175+/- 0.0019 1.5

LB 0.4981 +/- 0.0007 0.4

radius rA 1.2175 +/- 0.0055

radius rB 0.8591 +/- 0.0019

An additional two columns for recent surveys are provided in the reference. They are closer to the ALMA values than mine; very close, but their own error bars do not enclose the values obtained by ALMA, perhaps for a number of reasons described in the paper. As for the values I used, they were likely based on a significant figure reliable enough to report ( nearest tenth), if I had not made any transcription errors myself. But they suggest that our calibration of the luminosity and mass of the two stars has shifted considerably since then and asymptotically tapered off in recent times. Overall, A less massive and B more; same with luminosity. And in addition I note lower estimates of system age with time, more frequently assumed that they were as much as 9 billion years old. Maybe now 6 billion or about the same as our system 4.8 billion.

Still, as the numerical bounds on parameters decrease, the orbital uncertainties for astrometric studies decrease as well. As the paper notes with their results, based on position definitions defined against deep space quasar sources rather than local stars, within the stability bounds of 3 AUs or less, planets with masses in terms of 20 to 30 times that of Earth. It is noted that Proxima Centauri had been examined with Gaia resources, and identified as a distant partner of the Alpha Centauri system. But examination of the other two components was hindered by their brightness – as would be the case for several other nearby stellar systems such Sirius. Too bad.

Still, in summary, I consider the ALMA report a gold mine.