While I’m immersed in the mechanics of exoplanet detection and speculation about the worlds uncovered by Kepler, TESS and soon, the Roman Space Telescope (not to mention what’s coming with Extremely Large Telescopes), I’m daunted by a single fact. We keep producing great art showing what exoplanets in their multitudes look like, but we can’t actually see them. Or I should say that the few visual images we have captured thus far are less than satisfying blobs of light marking hot young worlds.

Please don’t interpret this as in any way downplaying the heroic work of scientists like Anne-Marie Lagrange (LESIA, Observatoire de Paris) on Beta Pictoris b and all the effort that has gone into producing the 70 or so images of exoplanets thus far found. I’m actually just pointing out how difficult seeing an exoplanet close up would be, for the goal of interstellar flight that animates our discussions remains hugely elusive. The work continues, and who knows, maybe in a century we’ll get a close-up of Proxima Centauri b. Until then, I need periodically to return to deep sky objects to refresh the part of me that needs sensual imagery (and also accounts for my love of Monet).

Herewith some images that would challenge even the greatest of the Impressionists to equal. We’re looking at the Milky Way with new eyes thanks to two related projects, the VISTA Variables in the Vía Láctea (VVV) survey and the companion VVV eXtended (VVVX) survey. Roberto Saito (Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina, Brazil) is lead author of the paper introducing this work, which includes close to 100 co-authors. VISTA is the European Southern Observatory’s Visible and Infrared Survey Telescope for Astronomy, run out of the Paranal Observatory in Chile. Its great tool is the infrared camera VIRCAM, which opens up areas otherwise hidden by dust and gas.

Image: This collage highlights a small selection of regions of the Milky Way imaged as part of the most detailed infrared map ever of our galaxy. Here we see, from left to right and top to bottom: NGC 3576, NGC 6357, Messier 17, NGC 6188, Messier 22 and NGC 3603. All of them are clouds of gas and dust where stars are forming, except Messier 22, which is a very dense group of old stars. The images were captured with ESO’s Visible and Infrared Survey Telescope for Astronomy (VISTA) and its infrared camera VIRCAM. The gigantic map to which these images belong contains 1.5 billion objects. The data were gathered over the course of 13 years as part of the VISTA Variables in the Vía Láctea (VVV) survey and its companion project, the VVV eXtended survey (VVVX). Credit: ESO/VVVX survey.

We’re dealing with some 200,000 images covering an area of sky that is equivalent to 8600 full moons, according to ESO, and 10 times more objects than released by the same team in 2012, based on observations that began two years earlier and ended early in 2023. Working over that timeframe allowed scientists to chart brightness changes and movement that can be useful in calculating distances on this huge scale.

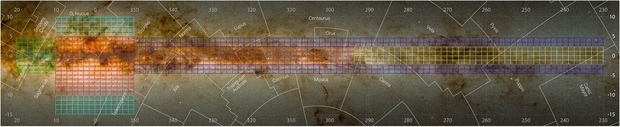

Image: This image shows the regions of the Milky Way mapped by the VISTA Variables in the Vía Láctea (VVV) survey and its companion project, the VVV eXtended survey (VVVX). The total area covered is equivalent to 8600 full moons. The Milky Way comprises a central bulge — a dense, bright and puffed-up conglomeration of stars — and a flat disc around it. Red squares mark the central areas of our galaxy originally covered by VVV and later re-observed by VVVX: most of the bulge and part of the disc at one side of it. The other squares indicate regions observed only as part of the extended VVVX survey: even more regions of the disc at both sides (yellow and green), areas of the disc above and below the plane of the galaxy (dark blue) and above and below the bulge (light blue). The numbers indicate the galactic longitude and latitude, which astronomers use to chart objects in our galaxy. The names of various constellations are also shown. Credit: ESO/VVVX survey.

The twin surveys have already spawned more than 300 scientific papers while producing a dataset too large to release as a single image, although the processed data and objects catalog can be found at the ESO Science Portal. More than 4000 hours of observation went into the work, and while the twin projects cover about 4 percent of the celestial sphere, the region covered contains the majority of the Milky Way’s stars and the largest concentration of gas and dust in the galaxy.

Clearly, a survey like this will be useful for observations from future instruments like the Vera Rubin Observatory, which will deploy an 8.4-meter mirror and the largest camera ever built for astronomy and astrophysics in a deep survey of the southern hemisphere at optical wavelengths. Instruments like the James Webb Space Telescope are obviously able to home in on objects with much higher resolution but cannot be used for broad area surveys of this kind. Next generation ground-based instruments will use the survey in compiling their target lists, and eventually the Roman Space Telescope will be able to produce deep infrared images of large regions with higher resolution.

As the paper notes:

…there are many more applications of this ESO Public Survey for the community to exploit for future studies of Galactic structure, stellar populations, variable stars, star clusters of all ages, among other exciting research areas, from stellar and (exo)planetary astrophysics to extragalactic studies. The image processing, data analysis and scientific exploitation will continue for the next few years, with many discoveries yet to come. The VVVX Survey will also be combined with future facilities to boost its scientific outcome in unpredictable ways: we are sure that this survey will remain a goldmine for MW studies for a long time.

But I fall back on sheer aesthetics this morning. As witness starbirth:

Image: A new view of NGC 3603 (left) and NGC 3576 (right), two stunning nebulas imaged with ESO’s Visible and Infrared Survey Telescope for Astronomy (VISTA). This infrared image peers through the dust in these nebulas, revealing details hidden in optical images. NGC 3603 and NGC 3576 are 22,000 and 9,000 lightyears away from us, respectively. Inside these extended clouds of dust and gas, new stars are born, gradually changing the shapes of the nebulas via intense radiation and powerful winds of charged particles. Given their proximity, astronomers have the opportunity to study the intense star formation process that is as common in other galaxies but harder to observe due to the vast distances. The two nebulas were catalogued by John Frederick William Herschel in 1834 during a trip to South Africa, where he wanted to compile stars, nebulas and other objects in the sky of the southern hemisphere. This catalogue was then expanded by John Louis Emil Dreyer in 1888 into the New General Catalogue, hence the NGC identifier in these and other astronomical objects. Credit: ESO/VVVX survey,

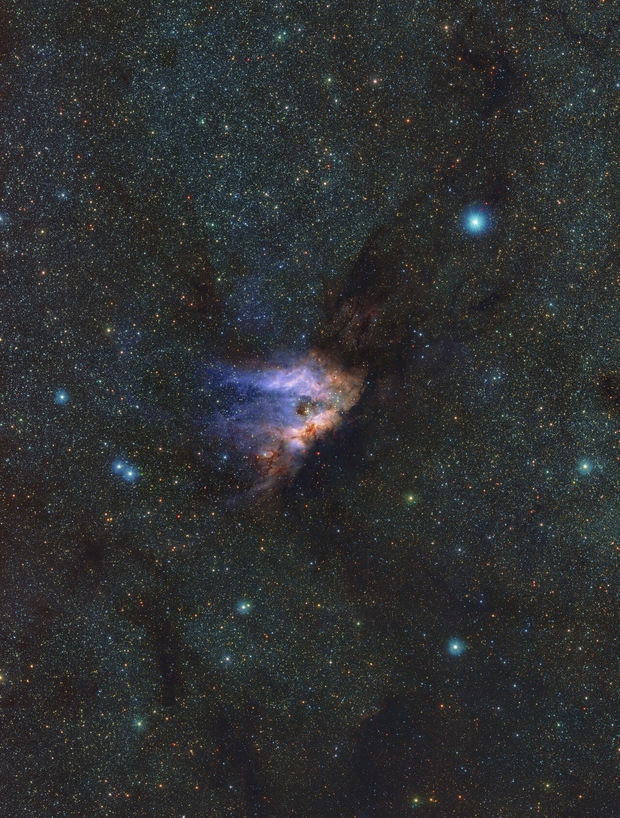

And a nebula inset into a riotous field of stars:

Image: This image shows a detailed infrared view of Messier 17, also known as the Omega Nebula or Swan Nebula, a stellar nursery located about 5500 light-years away in the constellation Sagittarius. This image is part of a record-breaking infrared map of the Milky Way containing more than 1.5 billion objects. ESO’s VISTA ― the Visible and Infrared Survey Telescope for Astronomy ― captured the images with its infrared camera VIRCAM. The data were gathered as part of the VISTA Variables in the Vía Láctea (VVV) survey and its companion project, the VVV eXtended survey (VVVX). Credit: ESO/VVVX survey.

The vistas opening up with our new technologies inspire a deep sense of humility. We are within and a part of what we are observing, which forces us continually to look with new eyes. I think of Carl Sagan’s frequent admonition that we are made of star-stuff. Or as T. S. Eliot put it in the “The Dry Salvages” (from Four Quartets):

For most of us, there is only the unattended

Moment, the moment in and out of time,

The distraction fit, lost in a shaft of sunlight,

The wild thyme unseen, or the winter lightning

Or the waterfall, or music heard so deeply

That it is not heard at all, but you are the music

While the music lasts.

We are the music. The immense VISTA data-trove will advance further discovery while igniting and shaping our imagination. Perspective frames the seasoned mind.

The paper is Saito et al, “The VISTA Variables in the Vía Láctea extended (VVVX) ESO public survey: Completion of the observations and legacy,” Astronomy & Astrophysics Vol. 689, A148 (September 2024). Full text.

As you like Monet, there is a new exhibition in London of his paintings of the Thames river at London.London calling: Claude Monet’s views of the Thames – in pictures

They seem to offer a new approach to the effects to J M W Turner’s earlier paintings, e.g. The Burning of the Houses of Lords and Commons.

`

Turner was remarkable. I’d love to see the exhibition in person if they are drawing some Monet/Turner connections.

Hi Paul

Monnet and the “impressionists” were the painters of light : do you not find the paralel fun with pictures of the universe ? For fun, visit here the house of Claude Monnet in Giverny and especially his worderfull gardens.

https://claudemonetgiverny.fr/en/useful-information/

https://claudemonetgiverny.fr/visite-virtuelle/index.htm

Yes, I’ve had the pleasure of touring the Giverny site, where my wife and I spent a lovely afternoon. As you can imagine, it was the thrill of a lifetime for someone devoted to Monet.

The denizens of the Thames riverbanks of that era must have suffered from chronic lung conditions including bronchitis and emphysema: perhaps the “blue bloater” and “pink puffer” designations for those two conditions may have had their origins about the same time.

IDK if it was much worse then, but as a resident of London from the 1950s, I can assure you the smogs were a major annual mortality factor. One had to wear a scarf over the face to reduce inhaling the smog particles, a way of life that was learned from childhood walking to school during the winter months. With the banning of coal for heating in the 1970s, the smogs vanished. Those fogs [ really smogs ] seen in old Hollywood movies of Victorian London are now a fading memory and no longer exist. As a result, it made sense to clean the outsides of historic buildings to restore their color. For example, the Houses of Parliament that used to be blackened by the soot are now restored to the pale sandstone color of today. City air is now poisoned with other noxious gases.

“The vistas opening up with our new technologies inspire a deep sense of humility. We are within and a part of what we are observing, which forces us continually to look with new eyes.”

I agree with this sentiment as do, I believe, the majority of regular CD readers. But it is far from universal, and by many is seen, at best, as an esoteric interest.

From my own experience, I see more common reactions to photos like these. The most benign are those that think “pretty” and flip to the next page in their media of choice without any real interest.

Another group, though less numerous, turn their backs on these picture, even while admiring the technology and scientific interest, as irrelevant. They focus on what they believe are far more important issues closer to home and are annoyed at the effort and funds expended that could be put to better use. To a degree, they perhaps have a point.

A far smaller group gets quite excited by these images and strives to make them better. There is a community of astrophotographers that go to extreme efforts to take their own images which they extensively process to produce beautiful pictures. An old friend of mine does this, and they are indeed striking and quite attractive.

However, not only has the scientific value been diluted out in that intense processing, I can’t help a feeling of sterility as I flipped through his albums of these pictures. They are no longer “real”. It’s particularly interesting since he was a working scientist throughout his career, though in an entirely different field.

I prefer the raw telescope images, or ones that have been moderately processed to improve their visibility or beauty for human eyes but, importantly, preserve or enhance their science value. While less visually stunning these images are more beautiful to my eyes.

@Ron

We are condemned to be “in the aquarium”; we can only observe our universe from within.

What you describe is related to the profusion of images now; there are so many and at such a rate, that the mind no longer fixes.

Before, it took several weeks to paint a painting and it was single. The world had time to admire it; to comment on it, to criticize it (Giotto, Raphael; the stained glass windows etc. even the peasant who can’t read could ask himself.)

The democratization of the picture has accelerated with technology inversely proportional to the time of reading these images (see : autochrome ; photo on glass plate & photo film)

This relationship is no longer because time has accelerated for three large numbers of people. You express it very well: “we SEE and turn the page”. From the Colosseum in Rome to the Parthenon in Athens, passing through the Effeil Tower, I have never seen anyone admire or question these things: a seflie and we leave. I find it sad. (nb : l Parthenon has very special proportions that are an architectural marvel ;)

There is a huge difference between “see” and “look”. We must learn not only to “make” an image – that is, what do we want to show, which portion of the real one is cut? Why? but also to interpret a work, in other words: reflect. What do R. Capa, R. Doineaux, D.Lange say us ? the question should be the same with Hubble, JWT & so on… Taking a photo is not pressing the button.

Here, the function of images is essentially a technical information value for scientists. However the photos are also beautiful and majestic by themselves.

The beauty of the universe – which is nothing empty cold and static in people’s minds – forces us to question ourselves. We cannot be insensitive to these images because they refer us to our own condition. Is it for that reason that these same people even if they do not always understand what a nebula is, they do not want to look at them? Too bad for them…

Astronomy & cosmology are rare accessible disciplines that advance.

>I prefer raw telescope images

So do I. First of all because we have the satisfaction of having spotted the object; of having handled its instrument. I have a 200mm I remember observing the ring nebula…a poor little gray circle pale and blurred as a round of cigarette smoke but I felt an immense emotion that night because it was MY observation.

Then because we are usually the only one to see the object in the occular, there is something possessive and magical. It’s a bit like when we developed a silver photo: there is a second “magic” when we see the photo appear in the bath: who did not understand can not. There is a satifaction that digital has killed.

Photo editing is an advantage for scientists (adaptive optics) that allows them to better extract information from a snapshot but at the general public level, it has become a “problem” in the sense that the raw photo is so “edited” by software to such an extent that it eventually loses its originality. Everyone wants to make the same photo as the one seen in a magazine, or copy those of Hubble…

It no longer really makes sense and especially the copy does not bring information. It is amazing.

A good picture is 80% success at the first shot when you press the shutter release which means work upstream and experience. You may be able to copy a Monnet or a Rembrandt but you will never make a Monnet or a Rembrandt because there is the sensitivity of the artist above all.

We can possibly CORRECT a picture but EDIT it, it is to make up and denature. Look at photos retouched in HDD they no longer have any meaning because we will never see such a landscape in reality…

What is interesting in the astrophotos that Paul presents us, is that we are spectators, we have a passive role which consists only of pointing at the instrument. The universe is revealed to our eyes in all its splendor… still have to look at it:)

I had the chance to study art history and an old teacher who taught us how to read pictures ;)

Our predecessors the mollusks inhabiting the ancient shallow seas saw a much bigger moon with a 21 day cycle reflected in the shell growth varying between high and low tide and between spring and neap tides.

We happen to be in a window of time and space where we are differently privileged in our access to views available to us; these views of this time and space and the technology to access them will inevitably flow by leaving this vista unique to our time and space.

Unprocessed images can have value, but they may often obscure much that can be displayed through processing. A common example was inappropriately exposed photographs which could be corrected by minimally capable Photoshop-like apps prior to the improved cameras on modern smartphones.

Even animals have varying visual abilities. There is one visual pigment for light and dark in the rods of the human retina and three pigments for three (human) primary colors in the retinal cones. Some folks have a variant of one of those three pigments. The pigments are encoded by the X chromosome, of which men have one and women have two. Those women who inherit the variant on one X chromosome and the normal pigment on the other have supernormal vision with four primary colors.

Four cone pigments in women

Some mollusks have fifteen visual pigments. Even honeybees see ultraviolet and patterns on flowers leading to the nectar. A raptor atop the Empire State Building is said to see a dime on sidewalk.

Original images are great, but even directly looking at objects we may not know what we are missing.

As you point out, we have very limited wavelengths that we can see, and some of us have greater or lesser capabilities in even that range.

Astronomy has made a wider range of wavelengths across the em spectrum, with the JWST focusing on NIR. On Earth, thermal imaging is used to expose information that we cannot see, and sound that we use poorly, but that other animals use with greater precision and detail.

To my mind, extracting information that is poorly displayed in raw camera images is useful, even to the layman. Don Dixon, known for his paintings still processes [digital] camera images to improve them in both layout and color, posting some to his Facebook account.

Given our variable eyesight abilities from color to acuity, any image is just within the capabilities of the instrument, from human paintings to cameras attached to telescopes or otherwise. Once the visible light images from Mt Palomar were the best we had, yet whatever that beauty, the newer images from better telescopes, digital cameras, and post-processing, enhance the images that, IMO, far exceed that of the old visible light images. Not for nothing is the Hubble image, “The Pillars of Creation” in the star-forming Orion nebula one of the most famous and well-known and reproduced astronomical images. IIRC, even this image has been superseded by JWST in resolution and detail.

While I think I understand Fred’s point about unprocessed images (and let’s not forget the amount of developing of the B&W image is dependent on who is developing the image), that argument reflects an older argument between paintings and camera images that was apparent in the C19th. While a camera cannot replicate the images of Monet (or Turner, or Van Gogh), it can show details that the painter cannot even imagine, such as thermal plumes and methane emissions over a city, the particulates in the air, or the UV reaching the ground, images that are just as expressive in their own way as paintings.

Don Dixon: astronomical art

I would like to share these photos of Leon FENET it was a French who lived in the 19th century in nord of France. He took extraordinary pictures of the moon with the means of the time that is photography on glass plate and his small telescope…

https://www.editions-libel.fr/maison-edition/boutique/de-loise-a-la-lune/