Bear with me today while I explore the pleasures of the Infinite Monkey Theorem. We’re all familiar with it: Set a monkey typing for an infinite amount of time and eventually the works of Shakespeare emerge. It’s a pleasing thought experiment because it’s so visual and involves animals that are like us in many ways. Now we learn from a new paper that the amount of time involved to reproduce the Bard is actually longer than the age of the universe. About which more in a moment, but indulge me again as I explore infinite monkeys as they appear in fictional form in the mid-20th Century.

In “Inflexible Logic,” which ran in The New Yorker‘s February 3, 1940 issue, Russell Maloney tells the tale of a man named Bainbridge, a bachelor, dilettante and wealthy New Yorker who lived in luxury in a remote part of Connecticut, “in a large old house with a carriage drive, a conservatory, a tennis court, and a well-selected library.” He has about him the air of an English country gentlemen of the 18th Century, interested in both the arts and science. An eccentric.

One night at a party in the city, Bainbridge enters into conversation with literary critic Bernard Weiss, who he overhears saying of a lionized author: “Of course he wrote one good novel. It’s not surprising. After all, we know that if six chimpanzees were set to work pounding six typewriters at random, they would, in a million years, write all the books in the British Museum.”

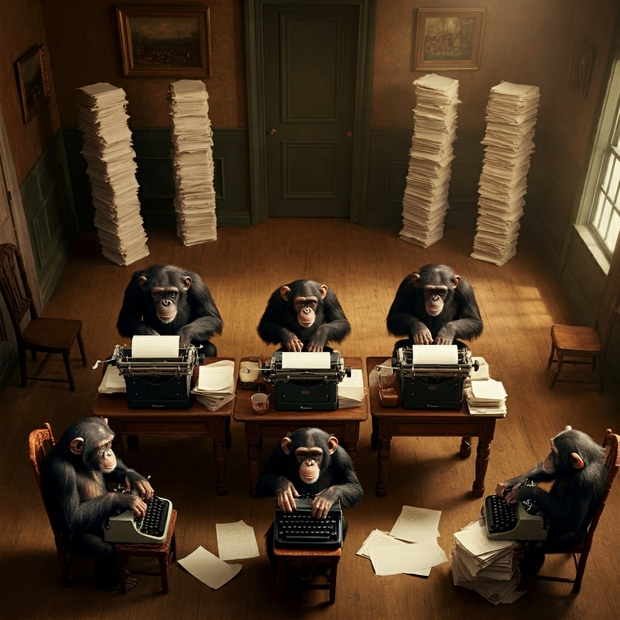

Impressed, Bainbridge learns that the experiment has never been tried. He acquires six chimpanzees and provides them with paper and typewriters. Some weeks later, he is with James Mallard, an assistant professor of mathematics at Yale, whom he has asked to his estate to discuss the ongoing experiment. Showing him the monkeys at work, he points to tall piles of manuscript along the wall, containing in each complete works by writers such as Charles Dickens, Anatole France, Somerset Maugham and Marcel Proust.

Image credit: Amazingly generated by Gemini AI. Note that the three foreground monkeys have their typewriters facing the wrong way, but I suppose it doesn’t matter, as they can still reach the keys.

Indeed, since the beginning of the experiment over a month before, not a single monkey has spoiled a single sheet of paper. Great literary works continue to pile up. After Mallard leaves, the weeks go by and the monkeys never cease their labors. They produce Trevelyan’s Life of Macaulay, The Confessions of St. Augustine, Vanity Fair and more. Bainbridge keeps passing this information on to Mallard, who grows increasingly confounded. And worried.

Finally, when leafing through a manuscript of Pepys’ Diary produced by Chimpanzee F (named Corky), a work that contains material not in his own abridged edition, Bainbridge is again visited by Mallard at his home. Taken back to the scene of the experiment, Mallard pulls out two revolvers and shoots the chimpanzees. Both men end up, after a fight, shooting each other and both die. Mallard’s last words: “The human equation…always the enemy of science… I deserve a Nobel.”

And so the story concludes:

“When the old butler came running into the conservatory to investigate the noises, his eyes were met by a truly appalling sight. A newly risen moon shone in through the conservatory windows on the corpses of the two gentlemen, each clutching a smoking revolver. Five of the chimpanzees were dead. The sixth was Chimpanzee I. His right arm disabled, obviously bleeding to death, he was slumped before his typewriter. Painfully, with his left hand, he took from the machine the completed last page of Florio’s Montaigne. Groping for a fresh sheet, he inserted it, and typed with one finger, “UNCLE TOM’S CABIN, by Harriett Beecher Stowe. Chapte…” Then he too was dead.”

Maloney was a Harvard grad who seeded ideas for many of The New Yorker‘s cartoons; he became editor and writer of the Talk of the Town section. Here he shows us what happens when something absurd becomes true. The story was reprinted in Clifton Fadiman’s Fantasia Mathematica (Simon and Schuster, 1958).

What would actually happen if we set up Bainbridge’s test? The new work exploring this is out of the University of Sydney, where Stephen Woodcock and Jay Falletta considered the problem within a more spacious context. Bainbridge was dealing with a tiny cadre of six monkeys. But most versions of the thought experiment involve infinity. Woodcock explains:

“The Infinite Monkey Theorem only considers the infinite limit, with either an infinite number of monkeys or an infinite time period of monkey labour. We decided to look at the probability of a given string of letters being typed by a finite number of monkeys within a finite time period consistent with estimates for the lifespan of our universe.”

This is the kind of thing mathematicians do, and I have often wished I had the slightest gift for math so I could join the company of such a jolly group. Or maybe that’s only in Australia, because I’ve known a few grim mathematicians as well. Whatever the case, the new paper appears in a peer-reviewed journal called Franklin Open. The authors assume a keyboard with 30 keys, which allows for all the letters of English along with the most common of the punctuation marks. They assumed that one key would be pressed every second until the end of the universe in 10100 years.

The latter are bold assumptions considering monkey finger dexterity as well as attention span, and I’ll also note that the end of universe calculation is very much up for grabs, although excellent books like Fred Adams and Greg Laughlin’s The Five Ages of the Universe deal with numbers like this. Still, we’re not exactly sure that the accelerating expansion of the universe is stable, or what it might do one day.

But enough of that.

Get this: There is a 5% chance that a single chimpanzee might type the word ‘bananas’ in its lifetime. But Woodcock and Falletta worked out two sets calculations, the second involving a population of 200,000 chimpanzees (200,000 is apparently the current global population of chimpanzees, although that number seems low to me). Anyway, if you throw the entire 200,000-strong retinue at Shakespeare, the Bard’s 884,647 words will not be typed before the end of the universe. As the authors point out:

“It is not plausible that, even with improved typing speeds or an increase in chimpanzee populations, monkey labour will ever be a viable tool for developing non-trivial written works.”

AI is another matter…

Of course, Mr. Bainbridge used only six monkeys, and look what he got. I think we can take the ending of the Russell Maloney story to be saying something about our attitudes toward science. Our essential understanding of probability had better be right. If it turns out we unleash monkeys who begin typing out For Whom the Bell Tolls, we are confronted with not just an improbability, but an assault on the structure of the cosmos. We can see why professor Mallard lost his wits and blew the monkeys away, an outcome that, had the story been written in our more animal-considerate times, would not have been allowed by the editor.

Mallard thought an impossibility could not be allowed to exist. He had saved science.

And I have to add the delightful conclusion from the paper:

Given plausible estimates of the lifespan of the universe and the amount of possible monkey typists available, this still leaves huge orders of magnitude differences between the resources available and those required for non-trivial text generation. As such, we have to conclude that Shakespeare himself inadvertently provided the answer as to whether monkey labour could meaningfully be a replacement for human endeavour as a source of scholarship or creativity. To quote Hamlet, Act 3, Scene 3, Line 87: “No”.

The paper is Woodcock and Falletta, “A Numerical Evaluation of the Finite Monkeys Theorem,” Franklin Open Vol. 9 (December, 2024) 100171 (full text).

This paper illustrates a common fallacy involving probability. It is very easy to gloss over an assumption like “each key is selected with equal probability on each press, independent of all other keys selected”. If any one of the monkeys takes a liking to the “E” key – or perhaps the apostrophe, depending whether you’re reading one of the uncomfortably authentic editions of Shakespeare – then it will complete the task in an inconceivably more rapid fashion, though still much more longer than we can imagine. Of course, if you start the project, some wag is bound to try dosing the apes with an ARHGAP11B construct and other assorted nootropics, whether out of curiosity or in the hope they can be stimulated to rebel in pursuit of their rights. Before long, all the monkeys (a term we shall use in the erudite cladistic sense only, scorning with merited disdain all those who tell us we are making a vulgar error) may well be capable of looking up Shakespeare on the Internet, and carefully typing out and copy editing until they accomplish their goal. It should be accomplished well within the lifespan of the Earth, let alone the Universe … unless we become obsessed with variations in manuscripts and the proper spelling of words in Shakespearean English, at which point the cause may nonetheless be lost.

And think of the number of copies of each work where there is just one character difference from the “original”! A rough estimate is that there are 4.5 million characters in the complete works. Therefore 4.5E6 copies with any 1-character error.

As any one of those characters could have 1 of about 30 character errors => 1.35E8 unique copies. Easily enough copies to fill a vast library and several times the number of books in the Library of Congress.

Lacking the infinite number of monkeys (and bananas) it would take to produce our near-infinite appetite for gibberish, mankind invented the LLM.

This paper seems to have hit the news too. Universe would die before monkey with keyboard writes Shakespeare, study finds. It struck me as rather frivolous.

Regarding the 1 chimp might have a 5% chance of writing “bananas” in its lifetime, that is a simple calculation.

Prob = Keystrokes_needed/lifetime_of_keystrokes.

Keystrokes_needed = keys^bananas_string_length = 30^7

lifetime_of_keystrokes = maximum_age_in seconds.

A calculator can do this calculation in seconds.

However, for those of us educated in the slide rule era, using approximations will give you rough estimates:

Seconds in year = 3600*24*365 = 31,536,000 ~= 31.5*10^6

round numbers = 4000*20*400 = 4*2*4 * 10^6 = 32*10^6 ~= 30*10^6

Keystrokes needed = 30^7 = 21,870,000,000 = 21.9*10^9

simplify 30~=32 = 2^5

30^7 = (2^5)^7 = 2^35

as 2^32 ~= 4*10^9 [Max range of 4-byte integers]

the 2^35 = 2^32 * 2^3 = 4*10^9 * 8 ~= 32&10^9 ~= 30*10^9

Age of the chimp? Lookup suggests 40 years

lifetime_of_keystrokes = 31.5*10^6 * 40 = 1.26&10^9

So probability = 1.26&10^9/21.9*10^9 = 1/17.4 ~= 5.8%

Using rounded numbers (40*(30*10^6))/(30*10^9) ~= 40/(10^3) = ~= 4/10^-2

~= 4%.

A “good enough” estimate.

Without a lookup, I would assume a chimp’s lifetime is between 10 and 100 years.

this would suggest a probability of between 1and10%

IOW, this calculation can be done approximately using mental arithmetic, no electronic prostheses are required.

The only novelty of the paper is in discarding the infinite number of chimps and typewriters and eliminating the infinite time to achieve the result.

Quantum computing is analogous to a [near] infinite number of computers running in parallel.

Just a reminder that Clarke already wrote an excellent short adopting this theme: The Nine Billion Names of God that won the Hugo for best short story in 1954.

The monks at a Tibetan monastery substitute for the chimps. The works to be reproduced are the expected 9E10 names of God.

The story hinges on the idea that a computer can generate those names far faster than the slow handwriting of the monks.

The denouement I leave for those who have not read the story.

Alex, I don’t know that I’d cite “The Nine Billion Names of God” as an example of a story inspired by the infinite monkey theorem: the divine permutations were generated by following a fixed, possibly quite simple algorithm, not randomly — much as one might write a straightforward program to solve the Tower of Hanoi game. And the faster output of the resulting list of names was due at least as much to the high-speed printers connected to the computer as to the computer/software itself.

Also, it was actually a Retro Hugo that the story won, as 1954 was a bit too early for a traditional Hugo.

@jms

I will have to disagree with your assessment of the concept. The names were based on permutations of the characters with some constraints – e.g. :

names up to 9 characters in length. The same character cannot be more than 3 in succession.

Granted the permutations are determinative rather than random to reduce repeat names and eliminate checking each new name against the accumulating set of names in a database. If you are lazy, generating random sequences within the length range, eliminating those that failed the valid name test, and only printing out the name if it was new would work too, just less efficiently.

IOW, I see no particular fundamental issue of the approach used in the story which was to speed up the unfinished manual approach by the monks that had already taken 3 centuries. If we replaced the monkeys with a high-speed computer, the output would surely be greater, although the time would still likely exceed that of the rest of the universe. Could a quantum computer, in principle, generate and test all possible random works of Shakespeare and find a perfect match?

A Hugo is still a Hugo, regardless of how it was awarded. Do you doubt that the story deserved it?

In the animated series Return to the Planet of the Apes from 1975, simian society had a character named William Apespeare who undoubtedly wrote plays.

Not to throw a monkey wrench into that paper’s calculations, but just saying…

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Return_to_the_Planet_of_the_Apes

And as none of us can or should have to wait around for those chimps, here are The Complete Works of William Shakespeare as already written by a third-order chimpanzee primate of the late Sixteenth and early Seventeenth Centuries…

https://shakespeare.mit.edu/

For those who like to read Shakespeare in one collected bunch…

https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/100

and…

https://ia801304.us.archive.org/2/items/cu31924071108454/cu31924071108454.pdf

Using monkeys or chimpanzees in the analogy would work if they are actually random character generators when sitting in front of a type writer. It turns out they are not. “In 2002,[13] lecturers and students from the University of Plymouth MediaLab Arts course used a £2,000 grant from the Arts Council to study the literary output of real monkeys. They left a computer keyboard in the enclosure of six Celebes crested macaques in Paignton Zoo in Devon, England from May 1 to June 22, with a radio link to broadcast the results on a website.[14]

Not only did the monkeys produce nothing but five total pages[15] largely consisting of the letter “S”,[13] the lead male began striking the keyboard with a stone, and other monkeys followed by urinating and defecating on the machine.” From this link: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Infinite_monkey_theorem#:~:text=A%20quotation%20attributed%20to%20a,know%20that%20is%20not%20true.%22

Randomness is far more difficult than most people imagine. pRNG regularly fail randomness tests, and humans that attempt to be random (e.g. “pick a number, any number!”) are truly awful. This is a topic I studied many many years ago in university. Monkeys don’t understand the concept so why should we expect it, even as a metaphor for randomness.

I remember being very impressed by a graduate student (I was an undergrad at the time) who explained to me the algorithm he came up with to generate a hash from random text that very reliably (but certainly not perfectly) that had an exceptionally low probability of colliding with hashes of different strings of text, whether similar or completely different. He went on to earn his doctorate by further developing the mathematics.

Again, randomness is difficult, really really difficult. We fail at the attempt, as do monkeys and computer algorithms.

@Ron

We fail at perfect algorithmic randomness, but plenty of natural processes generate as true a random sequence as you could want.

I recall way back in the late 1960s [?] a paper that had a title something like “Unicorns in the sequences” – an analysis of random number sequences generated by algorithms that showed anomalous patterns in the sequences.

“We fail at perfect algorithmic randomness, but plenty of natural processes generate as true a random sequence as you could want.”

In general this may be acceptable, but not for the topic under discussion. The numbers we are discussing are extremely large: time, characters typed, monkeys (real or hypothetical). A tiny deviation from perfect randomness has an enormous impact on the outcome. Think about it.

On a related note, there is no finite algorithm that can generate perfectly random sequences. How close you can get depends on the objectives of the experiment; that is, how much deviation can be tolerated before the experiment fails.

Indeed. If the probability of each character is biased, based on the frequency of the original text, it will shorten the time to achieve a perfect copy. Whether that shorter time will still be within the bounds of the age of the universe, I have no idea.

But really, this is like the apocryphal “How many angels can dance on the head of a pin?”.

How do you define perfect randomness and the deviation from it?

“How do you define perfect randomness and the deviation from it?”

I don’t have to define since it’s been done. It’s a well studied concept in mathematics. As usual, Wikipedia has a decent introduction:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Randomness

Thank you for the wikipedia link, but it’s of no use. These are not mathematical definitions. How can you be certain there is no pattern or there is no determinism? For example, can you calculate the deviation of the digits of pi from randomness as a number?

VIY, did you read the article and follow the relevant links? In there you’ll find mathematical procedures for testing (measuring) randomness and much more, including an answer to your last question. I mean, really, you could simply type “test for randomness” in any search engine and find what you want.

Again, this is a well studied field of mathematics. It is also especially important and studied today because so much of our modern dependence on privacy and security rely on measurably reliable randomness algorithms and tests.

‘But really, this is like the apocryphal “How many angels can dance on the head of a pin?”.’

I don’t disagree. I am simply engaging in the spirit of Paul’s article. I’m not taking it too seriously, even if there are interesting mathematical and physical ideas involved.

Ron has it pegged. I consider the infinite monkeys question a wonderful jest.

@ Ron. The answer is “all of them”. LOL

We are only considering mathematical monkeys here.

Not unlike spherical cows….

Spherical cows? That’s where meatballs come from.

No, computers can’t prove what Shakespeare really wrote

Story by Emma Smith • 1mo •

Did Shakespeare write Shakespeare? It’s unsurprising that Darren Freebury-Jones, a lecturer at the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust in Stratford-upon-Avon, asserts that he did. What’s more surprising is that, as this new book expertly shows, he did not write alone.

Shakespeare’s Borrowed Feathers is less about the “upstart crow” who upset the gossipy, close-knit world of the Elizabethan theatre, and more about those other writers whose influence, rivalry and collaboration shaped the canon we attribute to Shakespeare solo.

Here we encounter some familiar figures, including the luminary Christopher Marlowe, who transformed the stage through his poetic approach, as well as the Italianate John Fletcher, with whom Shakespeare wrote his last plays. The wit and gender fluidity of his comedies owe much to the courtly style of John Lyly, and his writing bears traces of some of Ben Jonson’s plays in which Shakespeare acted.

Noting some repeated phrases in Each in their own way [Every Man in His Humour, Jonson’s comedy], to Othello, Twelfth Night and Hamlet, Freebury-Jones makes an interesting case that Shakespeare was assigned the role of Jonson’s character – the role of Mateo, a wretch who wrote terrible poetry.

Full article here:

https://telegrafi.com/en/no%2C-computers-cannot-verify-what-Shakespeare-actually-wrote/

https://www.msn.com/en-us/news/world/no-computers-can-t-prove-what-shakespeare-really-wrote/

Regardless of teh results of textual analysis, we still cannot be sure who Shakespeare was. The glove-makers son, or the aristocrat Edward de Vere, Earl of Oxford, to name one candidate.

Of course this study is even more tongue in cheek and scientifically irrelevant than apparent. The projected life of the universe isn’t in any measure infinity.

Ah, but you overlook the concept of evolution! Monkeys typically live around 40 years as pets, so how many generations would it take for them to eventually develop an understanding of typing? If we provide them with bananas as a reward for every satisfactory attempt at typing, they might learn. Our ancestor primates evolved skills such as chipping rocks to create arrowhead spears for hunting large animals. By offering incentives, these monkeys could progressively enhance their abilities. Perhaps their specialty would be a book about the best types of bananas to eat!

Here is an example of a more advanced species trying to teach a less advanced technical species and not having much luck…

https://cufos.org/PDFs/books/UFO_REPORTS_INVOLVING_VEHICLE_INTERFERENCE.pdf

@Michael,

Well said. They might even write better versions of the plays and even excellent new ones that are better than the bard’s.

I grew up in a place where bananas grew natively, and every backyard had a few banana plants. Many varieties of bananas were available where bananas were sold.

Fortunately we don’t need to wait, the task has already been completed, without the need for any simian or silicon actors. If we merely scan through the infinite digits of pi we will find that the complete works of Shakespeare have been there all along. It may just take a while to find them but with an infinite sequence of digits that never repeats, the text must be there somewhere.

Indeed, we may expect to find them repeated there an infinite number of times. And within not only pi but any other transcendental number as well! Truly, Shakespeare is ubiquitous.

@Kevin

Channeling Sagan’s Contact? ;-D

I realized some time ago that I was unconsciously substituting “really, really, REALlY big” for infinity. That works for most things, but in mathematics you really need infinity. It started when I asked the question, “Which is bigger the set of positive integers or the set of real numbers?” The answer is they are the same size-both infinite. For any real number, say 3.141592654 you can assign an integer-since you have an infinite number of them. I then discovered there is whole branch of mathematics on really big numbers. Notwithstanding that (not being a mathematician) I think I can say that an infinite number of monkeys typing on an infinite number of typewriters for an infinite time could write an infinite number of copies of the works of Shakespeare. Which is the same size as one monkey on one typewriter writing for an infinite time. Or maybe one monkey on one typewriter writing infinitely fast. My head hurts.

Actually, there are infinities of different “size”. The set of real numbers is a larger infinity than the set of rational numbers (which includes integers).

Here’s a link if anyone is interested in learning more:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Infinity#Cardinality_of_the_continuum

This is why I prefaced my comment with stating I wasn’t a mathematician. I don’t have an intuitive feel for the relationship of cardinality and size for infinities. It’s fascinating stuff though.

It was Emile Borel, a French mathematician of the early 20th century who apparently proposed the idea of monkeys : https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/%C3%89mile_Borel#Works

Monkeys vs. apes: the difference is manifest even in the language: “monkeying” and “aping”.

As for monkeys as a proxy for randomness. Metaphorical monkeys throwing darts at a dartboard of stocks were posited to be as good a stock selection method as analysis. This was an assertion based on the Efficient Markets Hypothesis (weak or strong, take your pick).

The trouble is you can never find a good dart-throwing monkey when you need one. ;-D

A monkey is more likely to use just two keys. How does the probability of Hamlet in base 2 compare to Hamlet in more human language?

Within an infinite writing pool, a monkey sits typing the digits of pi. More importantly, are they within reach?

If we use 5 bits to code for the characters, it’s the difference between 30^n and (2^5)^n or 2^5n. If we have to use 8 bits, then it is much larger at 256^n.

However, if a modified morse code is used, just maybe it might be less time, but that would require some math that is much harder or more likely brute force simulation. ;-/

If the monkeys persist with that behavior we can always convert the binary sequences into Unicode text.

I think you’re on the right track looking for an alternate encoding that can be translated to the proper script, but perhaps not base 2. We need to consider compression algorithms … all of them. The tighter the compression, the more likely the monkey will come up with the right text. In any case, there’s an extra chance of a match for every algorithm we check. And if we invent one where “;” is a shorthand for the entire works of Shakespeare, well, then we’ll have a winner. :)

We can study the problem from different angles and this thought experiment has the merit of making us think about the notion of infinity. But I find that the paradox evokes above all the notion of determinism: either we assume that randomness will generate something structured (how ?); or we consider at first sight that a “mechanism” is some – for example, a genetic code ; computer, or basic “consciousness” – is included in the initial disorder which will interragate with its environment over time to structure itself and evolve towards a specific goal. There is randomness in our universes but today it is globally structured. Note that the “post-big-bang primordial soup is closer to our monkeys who start writing. So the question is : what makes it possible to structure things in a finite duration ?

It is difficult to see a universe in which there would be no time limits for any single factor present in this universe to bring something to the surface. In anticipation of this event, it would mean a “static” universe that would not interact with our monkeys until they produced Hamlet. This seems grotesque considering that interactions are everywhere.

Or you would have to imagine a universe that is totally and — constantly — chaotic, so without thermodynamics, in which I don’t think there’s much going out except…from disorder. Certainly, something is better than nothing;)

In our Big-bang model, the photons have finally sprung from the primodial “soup” of plasma following the cooling of the universe factor itself at its expansion. Of course it’s just a fun thought experiment.

here we learn that Cicero had already more or less formulated the problem :

https://www.newsweek.com/infinite-monkey-theorem-shakespeare-probability-universe-heat-death-1978099

@Fred

And don’t forget the formation of Boltzmann brains from randomness in the universe.

I was going to bring that up, in terms of the wildly improbable. Boltzmann brains give me nightmares if I think about them for any length of time.

Paul is having great fun with us. But I return to another topic.

Drake’s equation, and its updates, is ridiculously simplistic. The Fermi Paradox is the controlling observation.

The number of factors leading to or away from the development of intelligence may not be infinite, but we should consider that there are a large number of factors that ultimately produced humanity on Earth. We can observe practical experiments on Earth where an intelligent species did not develop tool making (dolphins, elephants, octopi, etc). We also have practical experiments on Earth where an intelligent species with tool-making abilities did not develop a technological culture (chimpanzees, one example). Even more, we have practical experiments on Earth where intelligent, tool-making humanoids did not survive the variable environment (Neanderthals, Homo Floresiensis, Denisovans, others we haven’t noticed). Going back in our history, the ascendancy of mammals seems to have been an accident that only happened because a large ecological niche was opened up by a meteor strike. There is a factor for us to consider – how many planets have life evolving and then experience a favorable (to intelligence) extinction event?

I bring this up because I don’t have the practiced mathematics necessary to calculate the probable rarity of advanced technological cultures in the universe, particularly not near here nor near now. But I too wonder, if they exist, where are they?

This is not intended to be pessimistic nor fatalistic. Realizing how rare and precious humanity may be (is in my view) should inform our whole civilization. If we don’t populate the universe with art, poetry, science, philosophy, who will?

>Paul is having great fun with us

Really ? ;) I noticed that he knows how to slide this kind of “open” subject between two purely technical articles just to see if we follow the course in the background of the class :)

>If we don’t populate the universe with art, poetry, science, philosophy, who will?

I reverse this pretty proposal and I say that the universe is art, poetry, science & philo and it’s up to us to appreciate it.

Wow Fred, what a delightful statement at the end!

Thank you Paul. How can I not be sensitive to such perfection ?https://apod.nasa.gov/apod/ap241102.html

BTW, I found a (real) monkey who made a beautiful selfie :

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Monkey_selfie_copyright_dispute

so, sometime, random can generate something :) I must say that the photo was so well done that I believed in an image generated by the AI

Back to the monkeys: Why doesn’t someone set up a random character generator on a computer (call it a monkey if you wish) that produces random characters from a specified set of ~70 (lower and upper case letters = 52 + numbers 0 -9 = 62 + punctuation marks, special characters, and the space character = ~70), and see how long it takes to produce 1 complete sentence (pick any sentence) with all the spaces and punctuation?

Here is one generator, (there are others): https://www.gigacalculator.com/randomizers/random-alphanumeric-generator.php

10 strings it produced:

AhRlwc9yk0ACX.?CFBtf2XCHmCUGHfVZyVc;:Gy6SxDl?6″Wtl

0xj8QcmP5PA.R5OUzTG1pYVB4exGz!tP8kqzcu:h5Toq5ISW8w

;6un’dSz”EVBomKu3tclB4q:vDC2upnzwIlcTF8iJrRB76z’hA

‘JdJm1G!oVS5XIKTRsY9kRAKl”dd!ItjLw.z0V1g0gfh?xF;S1

ov97M;jdFsIu4YYtKDqlaee13Er;’uj.BYLZyTE6E4ycO9EYe?

wa3vnE”0nc!H!gka?FjU.zG5F2y.U”fDZ7tu7u6cPv8ZJe7y4X

Ts42klzZ2K;ld’zccTHX79X8hVZ;IYtnLPtqDIgRIeuO??D0.’

EtJiClKp6fY;qcO.H;knfFQb7YBpusV19ZFQP6EltkW0y4YRUQ

.i4l:e;bpos!k0Bd!vLC?vLq:gYG7jAM:LjGLgpG8FeUlhe3Vm

Am59I4x7Dy7?pXGPCR5YzLGEa8XHkLjP6′?9gPc18h6jxm1v??

J.L.Borges explored literature and infinity in The Library of Babel

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Library_of_Babel

A wonderful recent look at this is in William Egginton’s The Rigor of Angels Highlly recommended for those interested in Borges, not to mention Kant and Heisenberg.

Yes, I read that story a very long time ago. In relation to Paul’s article, even if those monkeys get the job done, somehow, there will be difficulties finding the books we want. They’re in there, somewhere.

here is a kind of version of Babel’s library online :

https://libraryofbabel.info/

Borges’ Library would contain every text and thought written by literary Extraterrestrials. Every conceivable technology would be explained, somewhere, the secrets of dark matter and energy would be elucidated.

True. But Borges’ library was many, many times larger than the visible universe. Hard to browse in those stacks.