The space elevator concept has been in the public eye since the publication of Arthur C. Clarke’s The Fountains of Paradise in 1979. Its pedigree among scientists is older still. With obvious benefits in terms of moving people and materials into space, elevators seize the imagination because of their scale and the engineering they would require. But we needn’t confine space elevators to Earth. As Alex Tolley explains in today’s essay, a new idea being discussed in the literature explores anchoring one end of the elevator to the Moon. Balanced by Earth’s gravity (and extending all the way into the domain of geosynchronous satellites), such an elevator opens the possibility of moving water and materials between Earth and a lunar colony, though the engineering proves as tricky as that needed for a system anchored on Earth. Is it even possible given the orbital characteristics of the Moon? Read on.

by Alex Tolley

Image: Space elevator connecting the moon to a space habitat. Credit: coolboy.

It is 2101, and the 22nd century has proven the skeptics wrong about space. Sitting comfortably in an Aries-1B moon shuttle on its way to Amundsen City in the Aitken basin at the lunar south pole, I am enjoying a bulb of hot Earl Grey tea. Sadly, without artificial gravity, no one has worked out how to dunk a digestive biscuit in hot drinks. The viewscreen shows the second movie of our almost 24-hour trip. Having been transferred from a spaceplane (far better than those giant VTOL rockets that reduced the cost of space access and paved the way for our multi-planetary advances), the moon-bound shuttle has crossed the Clarke orbit, past the remaining telecomm birds that haven’t been obsoleted by the swarms of comsats in low earth orbit (LEO).

A strange string of bright glints catches my eye. They are arrayed in an arrow-straight line, looking like dew on an invisible spiderweb seeking infinity. Nothing seems to move, the objects just apparently hanging in space. The flight attendant notices my apparent confusion. “What are they?” I ask as she crouches down beside me. “That is the newly operational Spaceline, a geosynchronous orbit to lunar surface space elevator. Those lights are the elevator cars carrying supplies to and from the moon. “But they are not moving,” I say. “They are moving, but too slowly to notice at this distance”, she replies, smiling, as this was probably a common observational mistake by passengers on the Moon run. “We should be seeing the expanding set of facilities at the Earth-Moon Lagrange Point 1 (EML1) nearer the Moon. The captain usually puts a magnified image on the viewscreens as we pass.”

This post is about space elevators, but not the Earth to Geosynchronous orbit that is most known, but rather a lesser known lunar space elevator {LSE), and in particular the one that rises from the lunar surface and terminates somewhere between the Earth’s surface and the Earth-Moon Lagrange Point 1 (EML1).

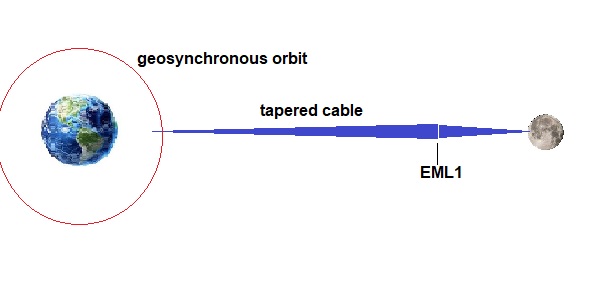

Because the Moon is tidally locked to Earth, an LSE from its surface can hang over the Earth, with the cable tension maintained by the gravitational pull of the Earth. Deployment of the cable is similar to the Earth space elevator (SE) which uses the Clarke orbit as a stable position that keeps the same point on the Earth below it, but in the case of the Moon, that deployment position is at the gravitationally neutral EML1. The cable is then simultaneously unrolled towards the Moon’s surface, and balanced by cable unrolled towards Earth and pulled towards Earth by gravity.

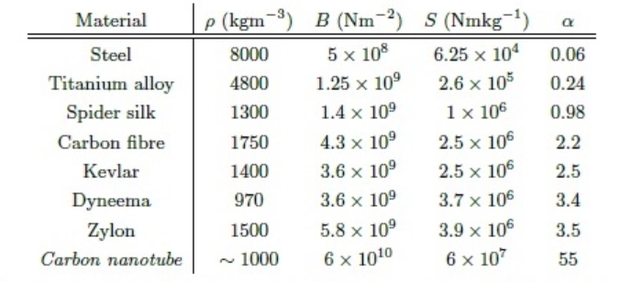

The idea of an LSE is not new and may even predate that of the Earth space elevator with a 1910 note by Friedrich Zander. Unlike the Earth space elevator that cannot be built as no material available can support its own mass, existing high-strength plastics like Zylon® can in principle be used today to build an LSE. Prior work by Pearson in 1979 on the LSE, and in 2005, with collaborators Levin, Oldson and Wykes published a NASA report on the LSE for two LSE cases, one passing through EML1 and the other anchored on the lunar farside passing through EML2 (using centrifugal force to tension the cable). These works and others demonstrated that an LSE could be built that would reduce the cost of transporting water and regolith to and from the Moon.

Prior work assumed that the cable would terminate in the Earth direction with a mass to provide the tension. The shorter the EML1 to terminus length, the greater the mass, and also the total mass of the LSE. A design tradeoff.

Image: The Lunar Space Elevator concept. A tapered cable from the Moon’s surface, through EML1 and terminating inside the geosynchronous orbit.

A 2019 arXiv preprint by Penoyre and Sandford adds their calculations for an LSE that they call the “Spaceline”. The authors show that a cable can be created without any counterweight between the Earth and the Moon, with the end of the cable dipping inside the geosynchronous orbital height. The total length of their optimal design is about 340,000 km, with a total mass of 40,000 kg (40 MT). The deployment facility and payload carriers are extra mass. The total mass of the system would therefore be lower than a design with a shorter cable and terminus mass. The authors also indicated that with the cable terminating inside the geosynchronous orbit, it would be easier to reach the cable from Earth and therefore reduce the transport costs further.

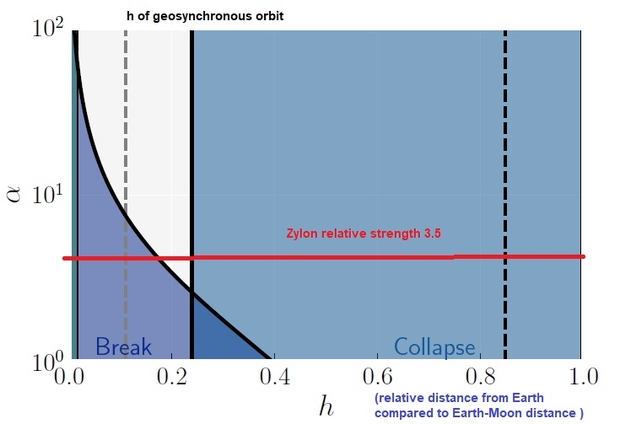

As with prior work, this all-cable design ensures that maximum tension in the cable is at the EML1 point, and declines towards both ends. The design ensures that the cable cannot collapse onto the Moon, nor break under load and fall towards Earth.

Table 1. Materials with values for density (ρ), breaking stress (B), specific strength (S), and relative strength (α). Materials with relative strength greater than 1.0 can be used in an LSE. Zylon have the highest relative strength that can be mass-manufactured. Carbon nanotubes can only be made in very short lengths at present. Source – Penoyre & Sandford.

This paper is primarily an exercise in designing an all-cable system using fixed area cross-sections, tapered cross-sections, and a hybrid of these two designs to simplify manufacture, deployment, and operation. Figure 2 shows that a Zylon cable of uniform cross-section suffices as an LSE that neither collapses nor breaks. Their calculations show that the tapered design is the most efficient with total mass, but the hybrid design using mostly uniform cross-section cable is a good compromise that simplifies manufacture and operation that reaches geosynchronous orbit.

Image: The white area is a feasible space for a cable of a uniform cross-section. With a relative strength above a critical value, a cable length can be constructed that neither collapses back to the Moon nor breaks under its own mass. Zylon can achieve this, albeit not to the desired geosynchronous orbit height. Not shown are the cases for a tapered and hybrid cable that can reach geosynchronous orbit. Source modified from Penoyre & Sandford

No attempt is made to determine other masses to support, such as the crawlers to carry payloads, how many could be supported, and the deployment hardware that must be transported to EML1. The assumption is that scaling up the area or number of cables will allow for the payload masses to be carried.

The authors do not justify the construction of the cable beyond showing that the cost of delivering payloads to the Moon, as well as returning material to space or Earth, is significantly reduced using a cable compared to spacecraft requiring propellant to transport the payloads.

The cost savings are not new, and no doubt a cable would be built if there were no other issues. But as with the SE, some issues complicate the construction of an LSE. Other authors have analyzed the LSE in more detail including survivability to space hazards [Eubanks], payload capability, speed of crawlers, ROI, and even transport of materials to and from the lunar South Pole to the LSE base on the lunar surface [Pearson et al, 2005].

So far so good. Penoyre and Sandford have shown that an unweighted cable can be used as an LSE which can stretch from the lunar surface to geosynchronous orbit, a mere 36,000 km from the Earth’s surface. Not quite as complete as the web between Earth and Moon in Aldiss’ Hothouse, but close. To reach the start of the cable, a spaceplane needn’t have to maintain geosynchronous orbit, but rather make a ballistic trajectory with the apogee reaching the terminus of the cable, and be captured by it similar to that of a skyhook, but with less difficulty.

But wait. Isn’t the paper skipping some important issues that could make this LSE impractical?

With the SE the geosynchronous orbit is circular. Once the orbital station is constructed and the cables reeled out to Earth and the counterweight, the system is very stable. This is not the case for the LSE.

The Moon’s orbit, with an eccentricity of 0.055, varies in distance from the Earth over its period from 362,600 km at perigee to 405,400 km at apogee, a difference of 42,800 km. This will result in the EML1 point moving back and forth towards the lunar surface about 36,300 km over the orbit, or about 18,000 km back and forth over the average EML1 distance. As the semi-major axis distance of EML1 to the lunar surface is about 57,000km, this is about a 2/3rd change in distance. Therefore the extra mass of the cable from EML1 to the lunar surface at apogee must be balanced by an extra length of the cable from EML1 to geosynchronous orbit, and vice versa at perigee. The base station at EML1 must therefore reel in or out cable continuously over the Moon’s orbital period. This is a dynamic situation that cannot fail or the LSE will be destabilized and potentially break or collapse.

Eubanks [2016] calculated that the micrometeoroid impacts would break a cable of uniform circular cross-section within hours, effectively breaking the cable before it could be deployed. The longer the cable, especially the long section between EML1 and geosynchronous orbit, the more quickly the break. A break in the cable would result in the section attached to the lunar surface falling back onto the Moon, wrapping itself around the Moon as it continued its orbit.

The other section would fall towards Earth, crossing the lower orbits and probably having a perigee that would enter the Earth’s atmosphere and likely burn up on entry over some time. Eubanks calculated that making the cable with a flat cross-section would ensure a lifetime between possible breaks of 5 years. Penoyre and Sandford acknowledged the danger of such breaks and also suggested a flat cross-section, although this would be less effective where the cable tapered.

While the LSE is relatively free of satellites and other artifacts, the question arises why the Earth’s terminus of the cable is inside the geosynchronous orbit. Geosynchronous satellites have a relative velocity of about 3 km/s relative to the end of the cable, posing a hazard to both satellites and cable. This is made worse if the cable length is not adjusted fast enough as it would dip deeper into the orbits of satellites with corresponding higher impact velocities and increased numbers of possible impacts. All this for the advantage of easier access to the end of the cable.

While accepting that cables with moving payloads are a cheaper way to transport material to and from the lunar surface, the speed at which these payloads can be moved is also relevant. An analogy might be that while walking across a country might be the cheapest form of travel, it is far slower than taking powered transport and time is important for commercial transport.

Various authors have used different assumptions of travel speed on the cable, up to 3600 kph (1.0 kps) [Radley 2017]. A more realistic speed might be 100 kph. At this speed, a payload from geosynchronous orbit to the lunar surface would take about 20 weeks. This is the same order of time to reach Mars on a Hohman orbit and similar to transoceanic voyages in the age of square-rigged sailing ships, This is entirely unsuited for transportation of humans or goods that can perish or be damaged by radiation from the solar wind or galactic cosmic rays. It would be suited for carrying bulk materials and equipment.

If the cable were a constant area flat ribbon, probably woven into a Hoytether [Eubanks 2016, Radley 2017], the payloads may not need to be self-powered but simply attached to the cable and moved like a cable car. Transport from the lunar surface to a station at EML1 would take about 3-4 weeks. Therefore people and some food supplies would still need to be ferried by rocket to and from the Moon.

While we think of the Moon as tightly locked facing the Earth, in practice it has a libration that would move the relative position of the lunar surface sideways back and forth over the month. This would send waves up the cable with a velocity dependent on the design of the cable. The dynamics of this oscillation would need to be investigated. Similarly, while Coriolis forces do not affect a static LSE, they will be a factor with the carriers moving on a cable from a low velocity at geosynchronous orbit to the Moon’s orbital velocity of about 1 kps. This is an order of magnitude higher than at the Earth terminus of the cable, and these forces will need to be determined for their effect on cable dynamics.

The authors also state that a base station of potentially immense size could be positioned at EML1 where the cable would be deployed. EML1 would be a convenient place to expand facilities making use of the zero gravity at that point. While Arthur Clarke had a manned telescope at EML1 in his novel A Fall of Moondust, EML1 is not a stable point or attractor, but rather unstable. This is made even worse by the orbit of the Moon which changes the position of this point and the surface over its orbit, as well as its position in orbit. As a result, the proposed Lunar Gateway space station is not placed at EML1 but rather in a Near Rectilinear Halo Orbit (NRHO) that requires far less fuel for station keeping. While the idea of a station at EML1 sounds attractive, it might be a costly facility to maintain, even with the advantage of having a cable to adjust its position.

Despite these caveats, there are good scientific and potential commercial reasons for reducing the cost of transporting mass to and from the Moon, as well as maintaining a facility close to the EML1. These have been explained in more detail by [Pearson 2005, Eubanks 2016]. I would add, as a fan of solar and beamed sails, that this could be a good place to deploy and launch these sails. There are no satellite hazards to navigate, and the low to zero gravity would allow these sails to reach escape velocity without needing the slow spiral out from Earth if started at LEO.

I propose that rather than having a cable reach geosynchronous orbit, it might be better to have a shorter weighted cable as proposed by Pearson even at the cost of a greater total mass of the LSE. Used in combination with a rotating tether in LEO (skyhook), transport to the tether could be achieved with an aircraft or suborbital rocket, attaching the payload to the skyhook, and having it launched into a high orbit to reach the end of the LSE. This would have to be a well-coordinated maneuver, reducing the costs even further albeit with the potential problems of skyhook and satellite impacts, especially with satellite swarms in LEO.

Our journey to the Moon has nearly ended. On the surface, I can see the long tracks of what looks like monorail lines. They were designed to launch packages of regolith or basic metal components into space, as originally envisaged by Gerard O’Neill in the late 20th century, to construct space solar power satellites and habitats. China’s AE Corp’s Spaceline (太空线) proved more economic, obsoleting the mass driver’s original purpose. They were repurposed to accelerate probes brought up from the Earth to the Moon, into deep space. One day their larger descendants will launch crewed spaceships on their journeys to the planets.

References

Penoyre, Z, Sandford E, (2019) The Spaceline: A Practical Space Elevator Alternative Achievable With Current Technology https://arxiv.org/abs/1908.09339

Pearson J, et al (2005) Lunar Space Elevators For Cislunar Space Development. Phase I Final Technical Report.

Eubanks, T. M. (2013). A space elevator for the far side of the moon. Annual Meeting of the Lunar Exploration Analysis Group, 1748, 7047. http://ui.adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2013LPICo1748.7047E/abstract

Eubanks, T. M., & Radley, C. F. (2017). Extra-Terrestrial space elevators and the NASA 2050 Strategic Vision. Planetary Science Vision 2050 Workshop, 1989, 8172. https://ui.adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2017LPICo1989.8172E/abstract

Eubanks, T. M., & Radley, C. F. (2016). Scientific return of a lunar elevator. Space Policy, 37, 97–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spacepol.2016.08.005

Radley, C. F. (2017). The Lunar Space Elevator, a near term means to reduce cost of lunar access. 2018 AIAA SPACE and Astronautics Forum and Exposition. https://doi.org/10.2514/6.2017-5372

In SF the oldest Space Elevator from a moon I know of is a yarn called “Atom Drive” in which a fluoride based cable is used to catch a Mars launched plane from Phobos. Arthur Clarke actually has the Mars Space Elevator built before the Terran version, though Phobos is treated as a hazard rather than an anchor.

Interesting, Adam. Who wrote the “Atom Drive” story, and where did it run?

Paul, I think that is this one by Charles L. Fontenay P58:

https://s3.us-west-1.wasabisys.com/luminist/SF/IF/IF_1956_04.pdf

Thanks, Fred. You really know your SF!

Do you have a reference? I cannot recall that from any of his stories, but memory fails me these days.

“Fountains of Paradise”, Chapter 23: “Moondozer” Alex Tolley.

Thank you. I read forward and got as far as the Martian elevator was going to be built, but it was unclear whether it was before Earth’s elevator. Morgan returns to building the Earth’s space elevator (the chapters on the tests) after the Martian test is done. I will need to reread much of the novel’s parts III-V to determine whether the Martian elevator is completed before the Earth’s. I will grant that the novel makes clear that the Martian elevator is easier to build and that the solution to avoid Phobos is mooted as a tourist feature!

Adam – the best chapter is 37. The billion-ton diamond. It is clear that the Mars’ Pavonic elevator has been built and Morgan expects it to be the first of many. The Earth elevator is still being built after the successful tests.

Clarke posited diamond as the material for the space elevator. Since then, the focus has been on carbon nanotubes. However, to date, we cannot manufacture these CNTs of sufficient length to be useful, even for terrestrial uses such as suspension bridges.

Ironically, the “Diamond Age” has arrived as we can now manufacture perfect synthetic diamonds cheaply in sizes that can be used in jewelry and at a price that is leaving De Beers in a dilemma as they are losing their cartel pricing control. This suggests to me that perhaps diamond nanofiber is indeed the material to manufacture a space elevator after all. [There is a carbon “diamond” with a hexagonal structure found as microscopic crystals in meteorites – Lonsdaleite – which is harder than diamond, although idk if it has better tensile strength than diamond.

So perhaps Clarke may be able to claim another “prediction” albeit posthumously.

[I’m just waiting for diamond coatings on surfaces to be common.]

As much as space elevators have fascinated sci-fi readers, the concept does need more creative development. Here it does look like they put the thing in the worst possible place, and not only because it would slice through the entire geostationary satellite ring. The tension can’t be reduced with statite propulsion achieved by mounting adjustable mirrors along those hundreds of megameters of cable, because much or all of the cable would be plunged into darkness during a solar eclipse. Yet it’s illuminating to show that moving the goalposts really is a way to win this game.

It would be interesting to see more about networks of momentum exchange tethers. Suppose you become genuinely confident that a ship can latch onto an orbital tether. Is it possible to play Space Frogger? Take a toy spaceship like the VSS Unity, snag onto a short disposable rotating tether that slices backward through the upper atmosphere, get released at the top of this merry-go-round with a higher, orbital, velocity, snag onto another rotating tether, get released again … at some point, dock with a geosynchronous elevator that is oriented straight up and down so that it doesn’t disturb other satellites, ride it upward, get released again, find another tether to fly into interplanetary space…

I agree with the suggestion to use space tethers (or rigid sky hooks). They do seem to be cropping up more in Sci-Fi. With two-way transport, momentum exchange maintains the system. It also seems a far better idea than “gravity highways” where low-energy transport utilizes favorable gravity gradients to navigate the solar system but with the trade-off of increased time. The key for momentum exchange is whether they can increase the average velocity of spacecraft over independent propulsion. In some cases, they probably can. In others, alternative approaches are better (e.g. magnetic “rail guns”). However, I suspect that these are all best used for cargo as targeting inaccuracies could spell disaster for passengers, whilst we tolerate cargo losses. There is also that human need to “be in control”. It provides mental comfort even if that control is illusory. [C.f. Clarke’s short story “Maelstrom II.]

Two-way traffic is to be encouraged, but I don’t feel like it should be necessary for an orbital tether. Suppose you have a 2000 km diameter tether from the Karman line to the top end of LEO, with one end close to “stationary” and the other moving 7 km/s, so I get the centripetal acceleration is (3.5km/s)^2/1000km = 1.25 gee. Anything shorter would have more acceleration to deal with. Well, if you have a 1 cm strip of mirror on each side of the cable, or alternatively a diffraction grating which can be tuned by an applied voltage (apparently several types of these are known), well, that’s 40,000 square meters of solar sail! More than enough to maintain position under the burden of a limited amount of one-way traffic, I presume, and also potentially useful for reducing the tension on the tether (which can be much shorter since it just needs to move you from one orbit to a somewhat higher one). Making the first tether any smaller than this would be nerve-racking because you don’t want to leave passengers falling back to the Earth while they wait to attach to the next tether. Such a 2000 km tether would be an enormous project, but at least it’s not 350,000 km.

However much the tether has to be raised to overcome momentum loss of one-way traffic, this approach is clearly a better one than the elevator for reaching space. It does have to deal with atmospheric drag and good rendezvous timing, but in return, it is cheaper and faster for humans to reach space. Whether it is still a good idea in our current situation with satellite swarms, idk. Is it worse to be hit by a satellite or debris in an independent space vehicle, or the higher probability of a tether cut and the vehicle released before orbit is released? [I applauded swarms of Earth observation satellites, comsat swarms not so much – although undersea cable cuts are clearly “sabotage” and not as reliable a solution as we had once hoped in a more peaceful world.]

Hmm, I found a figure from Robert Forward of 2.7 cuts per square meter per year from small meteoroids. Large debris was only 1/4 as likely as that to cut the tether, but he was writing in 2002… maybe it is the biggest risk now. It does seem that this is a large risk indeed when a tether this long is considered (2700 cuts a year for a half-mm cable?!) – and it’s not really a “cut” per se, but a plasma explosion neatly erasing everything within a small radius.

This was looked at quite a lot for the Earth space elevator an a number of solutions evaluated. The lowest mass solution is the Hoytether design which is a web-like design that reduces the exposed threads to the damage radius.

This shows the design. Hoytether multiline design. The greater length of the LSE makes this even more of a problem.

For rotating tethers the problem is far less. The mass of a [rotating] skyhook mitigates the meteoroid problem.

However, micrometeoroids are not the only objects in LEO. There are small parts like the tiny object that damaged a space shuttle window. Then there are the increasing number of fragments due to satellite collisions and the deliberate destruction of same. A rotating tether is moving through the satellites and debris, where even a small collision could break the tether, letting any attached spacecraft to be released before it makes it correct trajectory.

The same issue applies to space elevators. In 1979, when Clarke’s “The Fountains of Paradise” was published, the number of satellites was far fewer. There were geosync comsats, and a some large orbiting earth observation satellites (e.g. LandSat), spy satellites, and other satellites, but nothing like the number we have today. The Lunar space elevator that doesn’t reach geosyn orbit as proposed by most designs would avoid the hazard these satellite swarms present.

[BTW, I checked out the Isaac Arthur videos on space elevators and he clearly bases his video on the Pearson et al design that allows for reaching the lunar south pole. He also uses the term “rotorvator” for a rotating skyhook. I have Michael van Pelt’s “Space Tethers and Space Elevators” in my home library, which goes into some detail on these devices.]

Although I’ve always found the engineering challenges of such structures to be very interesting, it remains a solution in search of a problem. Considering those challenges, I’m willing to wager that advancements in propulsion will come long before the needed technology is sufficiently within reach to develop a positive business case for any kind of space elevator.

The same issue is raised on Earth. Build an expensive bridge or tunnel or leave the existing ferry service? For space or lunar elevators, the problem of destruction is everpresent, as was the Tacoma Narrows Bridge. I recall even the difficulty of building the Channel Tunnel between Britain and France in the 1970s/1980s before it was finally built. We have the same issue with the high-speed rail in California, where the escalating costs are likely making it economically nonviable (What would the Hyperloop system have cost when the idea was briefly in vogue?}. But as we saw with the collapse of a span of the Bay Bridge from Oakland to San Francisco in 1989, however expensive and delayed, it had to be rebuilt as road transport now required it.

I tend to agree with you that space elevators are currently economically too risky to build without existing demand to justify it. There seems no reason to “build it and they will come” for such structures.

We build systems to increase the capacity for humans. Cargo not so much. Apart from the Suez and Panama canals, we rely on cargo ships to transport goods across oceans, even as once proposals for transAtlantic tunnels were mooted. But for humans, air travel across oceans remains the better solution. Both the space elevator and the lunar space elevator are really only suitable for cargo. I cannot imagine such systems ever making more sense unless the travel pods were the size of cruise ships to spend the [long] journey time in.

“Build an expensive bridge or tunnel or leave the existing ferry service?”

Large, lengthy projects entail risk. I call to mind a recent multi-year rapid transit project that, when completed, ran into COVID and WFH. Reduced need for commuting therefore low usage of the new system.

“For space or lunar elevators, the problem of destruction is everpresent…”

Indeed, and the problem starts when construction starts. Until it can be made extremely robust it’s untouchable. Right now we can only predict technology that is marginally capable in a risk-free environment.

“But for humans, air travel across oceans remains the better solution.”

We alter behavior to fit the available technology. Air travel enabled more travel, but on the other hand I’ve flown overseas for a half day business meeting. Easy to do but absurd. At least with slow options (ocean liners or SE) you need a good reason to incur the time expense. Fast travel begets poor choices.

I agree that cargo is likely to be the business case if there is one. But I think that new space resources will stay in space for space projects, not funneled up and down gravity wells.

I have often thought would it not be better to have a tube instead of a cable, you can then send gases up the tube like oxygen, nitrogen and other energy gases.

Hi Michael

While that seems reasonable at first, a bit of thought you will realise it needs to work like hyper-velocity gas-gun to push the gas to orbital altitude.

For the moon or low g world such as ceres elevator just increase the pressure inside the tube and the gases eventually rise up the tube and leak out. Nothing really stops us putting a magnetic plug inside the tube either which pushes the gases up with say a magnetic relay system on the outside. It would be a challenge on earth or higher g worlds because the pressure at the bottom would be very high. Perhaps we could use a laser up the tube to heat the gases as well to encourage leakage out the top.

On Ceres water could happily be pumped up as well as the pressure would not be excessive at the bottom, it would allow us to move huge amounts of water around the solar system.

It can be used in reverse to decelerate a ship. The gas could be compressed as the ship travels down against the tube, compressing the gas, until it stops gently at the surface. There is no need to lose the gas/water vapor for either launch or landing.

Yes, the magnetic plug in the tube could be used to compress gas inside to slow craft down attached to the outside. But its main purpose would be to allow for large amounts of fuel or other mainly gaseous products to be sent up or down with craft traveling on the outside.

Beyond the mechanical and economic constraints, could it be envisaged that the structure is compensated in real time for all its deformations by hundreds of micro-sensors (G)PS positioned around it, which would constantly adjust it

by a actuator system or winch ? Modern electronics like Starlink should be an advantage…

Another paper about this project : https://www.thebrighterside.news/post/riding-a-space-elevator-to-the-moon-is-possible-using-todays-technology/

What I find interesting in the concept of “space cable” is that the human mind has found another way to free itself from the earth’s gravity without using considerable energy (propellant) simply by playing on the forces present. This is a nice idea because if you think about it, there are no multiple ways to leave our planet currently (let’s leave aside the dematerialization of Startrek ;) If it is only about transporting materials by cable, then the problem is limited “simply” to technical constraints (solidity; durability of materials…) since there is no need to worry about the safety of the Human outside his planet. If we want to use cable, then the problem becomes more complex.

Finally all this makes me think of the spider; it starts by pulling a thread that cannot bear its own weight then it increases the rigidity of the structure by other judiciously arranged wires (note that this way of doing is fascinating; where does it come from?) to finally create an ultra-light structure, occupying a maximum of space with a minimum of material or it can be walked.

Let’s be crazy: imagine a spider web between some objects of our solar system; the company would be collosal but once set up, wouldn’t it be more profitable for our short-range interstellar exploration missions? Of course it would be a little more visible for an ETI but this is another story;)

From a low mercantile point of view and to have an order of magnitude: what would be the total cost of this kind of cable moon-earth ?

#Fred – the article you referenced is based on the paper behind my post. There is no Earth surface to Moon surface cable. It cannot be built with existing materials and the relative movement of the 2 bodies prohibits this.

However, I am reminded of a far future in Aldiss’ novel (see the CD post The Long Afternoon of Earth. For the far greater distances between planets in our system, you are far better off using the friction-free vacuum of space to travel between points. The elimination of rockets is done by accelerating and decelerating the spacecraft at each end, whether by beamed sails, magnetic drivers, or other technologies that effectively use external energy sources. In KSR’s “Red Moon”, the Chinese Moonbase uses maglev to both launch and land small spacecraft on Earth.

Mike Serfas’s comment about momentum exchange tethers is another way to launch and capture spacecraft to avoid using rockets to escape gravity wells and provide the necessary delta_v for interplanetary travel.

erratum :

“the company” : read “the project”. Mistranslation from the french word.

I always like non-rocket launch ideas like this. Though instead of the spaceline, I prefer the space runway (an orbiting track which spacecraft land on to be accelerated to orbital speed; https://orionsarm.com/eg-article/6026bf4b007c9) and the aerovator (basically a space elevator that rotates horizontally to sling spacecraft into orbit; https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Space_elevator#Related_concepts).

A large gun would work quite well, the gases could be recycled somewhat by have vents to the side that go into cooling ducting.

This reminded me of when I was at school and part of a small group of friends playing with making solid fuel rockets with newspaper that was soaked in oxidant. We did not have any great success, but a solution I came up with was to launch the rocket in an enclosed tube. The gas pressure behind the rocket did most of the work to launch the projectile. This is very different from the open tube launchers used in the military with effective rocket propulsion.

Folks: Could someone explain the notion of ‘momentum transfer’ in the context of space elevators?

I’ve a good grasp of the underlying Newtonian equations, but application here really escapes me.

Opps!

A red-faced confession…the entire momentum exchange concept is the subject of a Wikipedia article. Worse: the article was linked above!

Look before leaping, as they say.

Michael

A well-done essay, Alex. Building a space elevator and/or rail launchers on the Moon certain makes sense, gravity wise. Now I just want to see if we can actually get humans back to the Moon and set up the necessary infrastructure for this to happen. I am not quite as certain that the US will be back there soon as I recently was, based on such recent events as delays with Artemis and the SLS.

Isaac Arthur always has something interesting to say on these grander and long reaching projects that may be of use:

https://isaacarthur.net/video/lunar-space-elevators/

https://isaacarthur.net/video/space-elevators-strategies-status/

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dc8_AuzeYKE

Earth orbit and the Moon are the keys to the rest of the Sol system and beyond.

I suppose we could have a smaller hanging elevator if we had an orbital velocity solid ring just above the atmosphere. We then hang our much smaller length cable on a magnetic system to the solid ring which moves at 8 to 9 km/s. But it seems a little complex for my liking though.

That would be the orbital ring, and it’s also been discussed quite a bit among space enthusiasts.

Space Towers

149,956 views – June 8, 2023

One day we may retire our rockets and instead reach the heavens by ascending towers so tall they dwarf mountains, and rise above the sky itself.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JALWHqUCLOM

Credits:

Space Towers

Science & Futurism with Isaac Arthur

Episode 398, June 8, 2023

Written, Produced & Narrated by Isaac Arthur

I thought about a tower a while back built in the deep sea where we store CO2 in the bottom of the tower to equalise the huge pressure and have a very large tower that reaches out most of the atmosphere. At great heights the temperature is very low allowing us to collect oxygen much more easily.

What if we swap length for surface area?

Awhile back I proposed two tethered statites.

The two tethers crossed each other in the shape of an “X”

Having the tethers use sunlight pressure to tack towards or away from each other—the intersection between the two cables can be raised or lowered.

Put a flying windlass at the intersection—it could play out or roll up a third cable.

If do-able, you save a very long elevator ride—and Muzak.

Speaking of space megastructures, this new paper on Dyson Swarms does not quite get how these things would work…

https://www.universetoday.com/articles/a-dyson-swarm-made-of-solar-panels-would-make-earth-uninhabitable

The paper:

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0927024825001904

I see no indication that the author has read about either Robert Bradbury’s take on Dyson Shells as hyperintelligent Artilects or James Nicolls’ view of Dyson Shells and Swarms as megaweapons.

Is this going to be as with SETI, where the scientists who finally start playing with notions beyond the traditional mainstream thoughts on the subject require several decades to catch up with the pioneers and mavericks who had the more daring and original ideas in the first place?