Exactly how astrophysicists model entire stellar systems through computer simulations has always struck me as something akin to magic. Of course, the same thought applies to any computational methods that involve interactions between huge numbers of objects, from molecular dynamics to plasma physics. My amazement is the result of my own inability to work within any programming language whatsoever. The work I’m looking at this morning investigates planet formation within protoplanetary disks. It reminds me again just how complex so-called N-body simulations have to be.

Two scientists from Rice University – Sho Shibata and Andre Izidoro – have been investigating how super-Earths and mini-Neptunes form. That means simulating the formation of planets by studying the gravitational interactions of a vast number of objects. N-body simulations can predict the results of such interactions in systems as complex as protoplanetary disks, and can model formation scenarios from the collisions of planetesimals to planet accretion from pebbles and small rocks. All this, of course, has to be set in motion in processes occurring over millions of years.

Image: Super-Earths and mini-Neptunes abound. New work helps us see a possible mechanism for their formation. Credit: Stock image.

Throw in planetary migration forced by conditions within the disk and you are talking about complex scenarios indeed. The paper runs through the parameters set by the researchers as to disk viscosity and metallicity and uses hydrodynamical simulations to model the movement of gas within the disk. What is significant in this study is that the authors deduce planet formation within two rings at specific locations within the disk, instead of setting the disk model as a continuous and widespread distribution. Drawing on prior work he published in Nature Astronomy in 2021, Izidoro comments:

“Our results suggest that super-Earths and mini-Neptunes do not form from a continuous distribution of solid material but rather from rings that concentrate most of the mass in solids.“

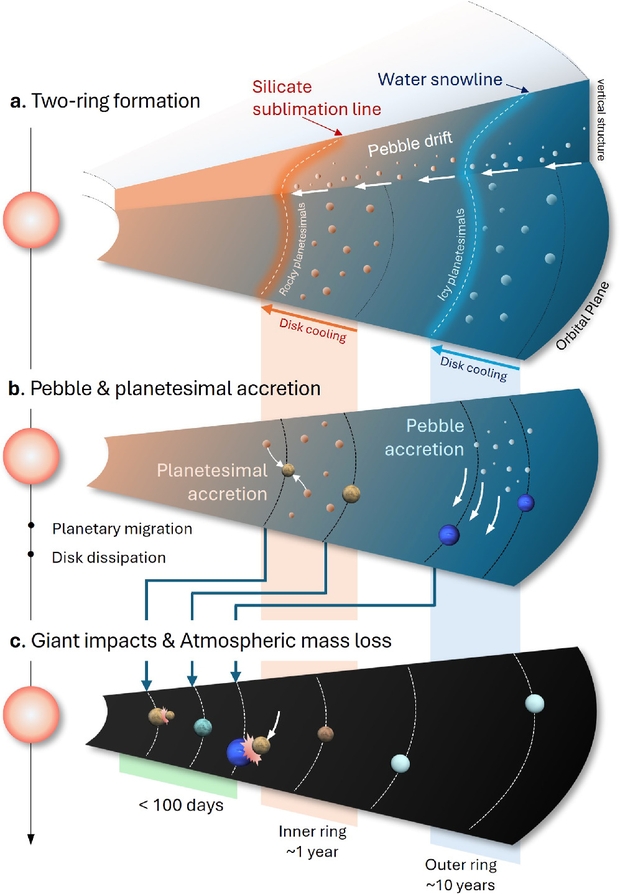

Image: This is Figure 7 from the paper. Caption: Schematic view of where and how super-Earths and mini-Neptunes form. Planetesimal formation occurs at different locations in the disk, associated with sublimation and condensation lines of silicates and water. Planetesimals and pebbles in the inner and outer rings have different compositions, as indicated by the different color coding (a). In the inner ring, planetesimal accretion dominates over pebble accretion, while in the outer ring, pebble accretion is relatively more efficient than planetesimal accretion (b). As planetesimals grow, they migrate inward, forming resonant chains anchored at the disk’s inner edge. After gas disk dispersal, resonant chains are broken, leading to giant impacts that sculpt planetary atmospheres and orbital reconfiguration (c). Credit: Shibata & Izidoro.

Thus super-Earths and mini-Neptunes, known to be common in the galaxy, form at specific locations within the protoplanetary disk. Ranging in size from 1 to 4 times the size of Earth, such worlds emerge in two bands, one of them inside about 1.5 AU from the host star, and the other beyond 5 AU, near the water snowline. We learn that super-Earths form through planetesimal accretion in the inner disk. Mini-Neptunes, on the other hand, result from the accretion of pebbles beyond the 5 AU range.

A good theory needs to make predictions, and the work at Rice University turns out to replicate a number of features of known exoplanetary systems. That includes the ‘radius valley,’ which is the scarcity of planets about 1.8 times the size of Earth. What we observe is that exoplanets generally form at roughly 1.4 or 2.4 Earth size. This ‘valley’ implies, according to the researchers, that planets smaller than 1.8 times Earth radius would be rocky super-Earths. Larger worlds become gaseous mini-Neptunes.

And what of Earth-class planets in orbits within a star’s habitable zone? Let me quote the paper on this:

Our formation model predicts that most planets with orbital periods between 100 days < P < 400 days are icy planets (>10% water content). This is because when icy planets migrate inward from the outer ring, they scatter and accrete rocky planets around 1 au. However, in a small fraction of our simulations, rocky Earthlike planets form around 1 au (A. Izidoro et al. 2014)… While the essential conditions for planetary habitability are not yet fully understood, taking our planet at face value, it may be reasonable to define Earthlike planets as those at around 1 au with rocky-dominated compositions, protracted accretion, and relatively low water content. Our formation model suggests that such planets may also exist in systems of super-Earths and mini-Neptunes, although their overall occurrence rate seems to be reasonably low, about ∼1%.

That 1 percent is a figure to linger on. If the planet formation mechanisms studied by the authors are correct in assuming two rings of distinct growth, then we can account for the high number of super-Earths and mini-Neptunes astronomers continue to find. Such planets are currently thought to orbit about 30 percent of Sun-like stars, meaning that there would be no more than one Earth-like planet around every 300 such stars.

How seriously to take such results? Recognizing that the kind of computation in play here take us into realms we cannot verify through experiment, it’s important to remember that we have to use tools like N-body simulations to delve deeply into emergent phenomena like planets (or stars, or galaxies) in formation. The key is always to judge computational results against actual observation, so that insights can turn into hard data. Being a part of making that happen is what I can only call the joy of astrophysics.

The paper is Shibata & Izidoro, “Formation of Super-Earths and Mini-Neptunes from Rings of Planetesimals,” Astrophysical Journal Letters Vol. 979, No. 2 (21 January 2025), L23 (full text). The earlier paper by Izidoro and team is “Planetesimal rings as the cause of the Solar System’s planetary architecture,” Nature Astronomy Vol. 6 (30 December 2021), 357-366 (abstract).

Does this analysis have anything to say about habitability, especially where rocky super-earths end up in orbits within or outside their star’s HZ? Their greater mass implies that their atmospheres may be thicker and denser, and less likely to be stripped. What about water content? For life, a planet doesn’t need to be Earth-sized, although a super-Earth’s civilization may have more difficulty reaching space without more energetic propulsion systems for rockets, and space elevators may be out of the question. But that doesn’t mean that they couldn’t be space faring. What would life be like on such worlds – would the denser atmosphere more than compensate for the higher gravity allowing more animals to fly or even float (like fish)? Could the biosphere be richer and more diverse than our own. If a hycean world, would we see mostly swimming and flying/floating animals, but few legged animals, except on the ocean bottom? What would the atmosphere composition be – more CO2 and H2? How would that impact energy capture and presumably carbon fixation? Would it affect our expectations of biosignatures?

The piece says they’d probably have >10% water content. Not so much a “water world” as a planet with a layer of extremely hot water, high-pressure ices, etc.

Those are good questions and we have to take them as being theoretically a high probability since we use first principles. An Ocean world does not have a carbon cycle so the oceans would take all the carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere through solubility and without plate tectonics it would not be recycled. Volcanism should still exist and put some gases back into the atmosphere. It is frustrating that we still don’t have any spectra of super Earths as that data is slow in coming. It would tell us a lot.

Although there could be a period where pebbles and planetesimal accretion occur simultaneously, it would seem logical the the pebble accretion being more efficient preceded planetesimal collisions. Dust first and gas first, pebbles and then planetesimals to planets.

This highly innovative theory explains the origin of water on Earth.

Five million years after the Sun’s birth, asteroids in the main belt release water vapor under the influence of solar energy. This vapor bath gradually diffuses into the inner Solar System, eventually enveloping the planets, which capture part of it, contributing to ocean formation between 10 and 100 million years later.

https://www.techno-science.net/en/news/this-highly-innovative-theory-explains-the-origin-of-water-on-earth-N26276.html

A new theory explains how water first arrived on Earth.

https://phys.org/news/2025-02-theory-earth.html

What is particularly interesting is how this process could impact the development of super-Earths and the distinction between them and mini-Neptunes.

1 out of 300 isn’t bad odds, though. 40-80 billion G-Type main sequence stars means about 130 million to 260 million in our galaxy.

It sounds like we might be swinging back towards “Jupiter as a blessing” with this kind of thing. If it moved inward and expelled all the nascent super-earths/mini-Neptunes, maybe that made it easier for smaller rocky planets to form.

Gradually, set by step, we are learning the rules of planetary formation, which will tell us how common/rare Earth analogs are. And this is another step forward.

The big difference between our system and systems with close in planets is that our system had very little migration inward. The silicate condensation line in our system runs between Earth’s and Venus’s orbit and the terrestrial planets almost form a bell shaped mass curve around this point. So, it appears that to get Earth analogs, we need a gas giant to form at the snow line to stop the inward migration of material.

From my survey of K stars that I did earlier this year, if the resonant chain is four or more planets long, you get a planet in the habitable zone, but it’s probably an ocean world. There is also the odd scattered world in the habitable zone, but they have highly elliptical orbits.

However, these are all planets larger than Earth. There’s been some good news on the sub-Earth front though. Four planets have been discovered around Barnard’s star ranging in mass from fifth to a third of Earth’s mass in a system that resembles a scaled up version of Jupiter’s moons. They are all inside the habitable zone, the outer one getting the same sort of instellation as Mercury. If we consider Proxima Centauri as a single star, then the two closest single stars have planetary systems, which points to every single star having planets, just some are too small to detect yet.

To retain an atmosphere +/- 1 bar, how much smaller in mass can a planet become?

Does it need to be large enough to maintain a magnetic field? [If Mars had a magnetic field, would it have been able to retain a thicker atmosphere, or was it too low mass to matter?]

It isn’t clear from the paper, but I understood the water ricjh worlds would be formed in the outer disk band and would become icy worlds. If they migrate inwards, they become hycean worlds in the HZ. The paper’s figure 6 shows such a water-rich around 2 AU (outside Mar’s orbit but inside Ceres) which may be icy or watery depending on its atmosphere, and one well inside the orbit of Mercury so I wonder if that water would be lost leaving a dry rocky world.

Their model seems to show inward migration is quite common, which seems to imply that super-earth but wet worlds may be quite common in the HZ. If so, we should consider what such life may be like and whether biosignatures need to be adapted for these worlds. For example, these worlds would not have shallow seas and shorelines. Photosynthesis would be from unicellular organisms, with any macro “plants” unanchored “floaters”. Would animal life be restricted to unicellular organisms, or could complex life live in these deep oceans (where would they reproduce?), possibly living in/on floating complex life like animals living on Sargassum in the Atlantic Ocean? There would not be bacterial stromatolites, but there would likely be bacterial colonies around hot ocean vents. Could complex life evolve at these locations or would life be restricted to unicellular types? I would like to think life is very adaptable and a large variety of complex life forms evolve in these oceans, perhaps with very unique life cycles adapted to the conditions on these water worlds.

>To retain an atmosphere +/- 1 bar, how much smaller in mass can a planet become?Does it need to be large enough to maintain a magnetic field?<

There's a lot of argument about this, but I would point out that Venus has no magnetic field yet retains a very healthy atmosphere.

What I would point out is the paper's results are frequency distributions over a large number of systems not an individual system. Rocky planets with a radius around 1.4 x Earth's are more likely to be in close orbits and icy-planets are more likely to be both more frequent and larger further out. (This is from fig. 5 which is hard to interpret as the lower panel has a different scale and its logarithmic.)

What I get from fig. 6 is that once the planetary cores form, they march relentlessly inwards until the gas disk disperses, all the while colliding with planetesimals, increasing their mass. The also perturb each other's orbits, increasing their eccentricity, which can result in orbital shuffling with outer planets moving inwards and inner planets moving outwards. The final arrangement of the systems is the result of a chaotic process. Neat resonant chains like the Trappist 1 system indicate a low level of chaos, but in any given system, counting out from the star, you cannot say were any given planet originated from, only what its statistical likelihood of were it came from. You could get a system were the planets go rocky, icy, rocky, icy, rocky, icy.

Given the density gradient of our solar system's terrestrial planets, they appear to be formed with very little chaotic shuffling, which is another indication of little migration as a result of late formation after the gas disk dispersed. In other words, our systems planetary formation is nothing like ones of those examined in the paper.

I'm not sure that ocean planets can develop life as at the bottom of their oceans, there is not rock, but high pressure ice, so it would be a sterile environment lacking the chemicals and minerals to catalyze life.

Hi Paul

“That 1 percent is a figure to linger on” your right there Paul and the model does seem to relate to a lot of exoplanet system discovered. I’m sure Jupiter has had an impact here in our solar system too.

An interesting post and one of my favorite research areas too.

Cheers Edwin

I have not read the publication but does it consider that the gravitation forces around the star and its accression disc are the same everywhere in its model? It seems to me that the rotation speeds of the accression disk will be lower if the star is close to a super-massive object, like black hole ?

Hive

They arrived at Beta Centauri,

a bubble emerging from the hot bath

of space/time, stirring, swelling, Pop!

Quantum Entanglement had set free

the perpetual wanderlust of humanity.

A first dangerous experiment in FTL

sent 8 brave souls to Beta Centauri D,

to test the systems: would it all work well,

navigation, communication, crew rotation

and to find out how it was going to be.

It took them 8 days to get past the moon,

then to arrive at the far destination, only

14 hours, arriving fast but not too soon. Relieved they didn’t arrive before they left, which had once been a major worry.

Planet D in the best orbit of that star

was uninhabitable, the others too.

All the moons were cold, by far too cold.

Nonetheless the mission. Ground stations orbital beacons, science labs deployed.

Everything confirmed working so they headed back, briefly stopped at Mars

to drop the same assets set out afar,

this to provide baseline and control

even though they knew it all worked.

Mars to our moon 2 minutes, it was grand.

Then 8 more days to reach home. Word

went out, every channel, in every tongue. We all soon knew, in every sovereign land

the age of interstellar travel had come.

Soon a thousand ships were launched,

one to every known destination, and more

planets were discovered everyday,

almost always habitable by something,

the whole universe was teaming with life.

Creatures could sing, as well as a whale

can sing, dance as well as a muskrat

dances on his burrow or duck and bob

like a parrot seeking a mate. Some could build too, as a small bird makes a nest.

On other worlds the inhabitants were found more industrious and organized, seemingly. Though looking very different from honey bees, fire ants or wasps,

they work hard constructing their hives.

An LLM of life forms was set up to learn,

about a cosmos of creatures living lives

different in detail but not different in kind

to those we see on our own planet, amazing diversity, amazing life on Earth.

A monkey with a typewriter never wrote

a sonnet. Whales sing, but not an opera.

Elephants remember, what they can’t say.

Not one songbird could ever sing a note

that her mother hadn’t sung before.

All this was trained into the LLM,

then a thousand ships went to the stars

collecting data on everything alive,

observing and testing every nest and hive

for behaviors and capacities like ours.

But nowhere did anyone find

a creature resembling humankind.

Tool makers indeed were found,

using tools picked up the ground,

all of them victims of their environment.

A ship’s captain wrote home to her lover:

“I’ve traveled the universe,

searched the skies

but never found a match

For the beauty of your eyes.”

After an interminable amount of time

the LLM came up with an answer

couched in the form of a rhyme:

My serious conclusion is that you lot

had best learn to keep and protect

What you have already got…

One quibble: I think by Beta Centauri D you mean Alpha Centauri B d. Beta Centauri is actually another star, quite distant from the three Alpha Centauri stars. But I don’t mean to detract from a flight of imagination…

Thank you. I debated w myself about the choice of destinations. And this is still in revision for a workshop I’m in…

Got it. And looking back, I see that you intended Beta Centauri all along. Sorry. I see ‘Centauri’ and always think Alpha Centauri, but there are plenty of stars in Centaurus!

What’s the workshop you’re involved in? SF writer’s group of some kind?

Thanks again. It was a poetry workshop, which is now over thankfully. I’d like to find a syfy writer’s workshop but I haven’t even looked.

But in 1956, when I was nine, I cut my foot and was laid up for awhile. I read every syfy book in the Phoenix public library. Reading the masters is a pretty good workshop, eh?

Sounds like me in the St. Louis library system back in that same era!

If I understand the modeling correctly ( and I often don’t), this scenario is based on a G Main Sequence star similar to the sun, including its conditions of formation.

Well, if we assume that the case described above is based on a nascent star destined to grow into a G2V like the sun, it contrasts with most of our exoplanet database for HZ exoplanets, associated with red dwarfs ( M1V to M9V).

There are a couple of reasons for that. For one, despite their dimness from afar, there are so many more of them. Locally and likely far beyond the neighborhood where they can be detected. Like Lincoln’s common people except as inhabitants of our galaxy. Also, when we look for HZ planets of any size, the red dwarf habitats provide shorter years. The campaigns to detect the planets go faster. Who knows how many objects of interest remained so because Kepler or successors simply ran out of time. But it is not only because the Earths, Super Earths and such are on geometrically shorter orbital paths. They are moving faster as well because of the mass-luminosity relation. And since the HZ has an associated orbital velocity higher than here at home, … Well, are all the dynamic assumptions going to remain the same?

From time to time I try to track down stellar formation scenarios that distinguish between G and M stars. Extrapolating from what I can find, the sequence of events slows down for the less massive stars. Or my guess: If a G star’s circumstellar disk disperses within ten million years to reveal nascent Earths, it might take several times as long to get the M dwarf to do the same. So I am led to suspect.

Now there are, of course, some well known tightly packed ( w. r. t . orbital distances) systems of Exo-Earths such as orbiting in circular paths around Trappist 1. But then again, before transits dominated the discovery process, doppler radial velocity detections included many highly eccentric jovian mass planets closer to their G star primaries than Jupiter. Assuming transit discovery systems were never perfected, we would have had a very different view of exoplanets in the galaxy as a result. Based on the lowest hanging fruit for that detection method.

Based on all these disparate modeling and detection trends, it still might be too early to draw sweeping conclusions. Not necessarily a bad thing.