The key lesson of exoplanetary science is surely humility. Over and over again, starting with the discovery of the first ‘hot Jupiters,’ we’ve been brought face to face with the fact that assumptions long enshrined in our thinking have to be reevaluated. Thus it’s no surprise to learn of a new study identifying what appear to be enormous debris disks around two giant stars. In the past, stars of their size were considered unlikely candidates for planetary systems.

The stars are R 66 and R 126, both located in the Large Magellanic Cloud; the former is 30 times more massive than our Sun, the latter 70 times. Both are thought to be descendants of the massive objects called type O stars, large enough that, if they were located in our own Solar System, they would swallow all the inner planets including Earth.

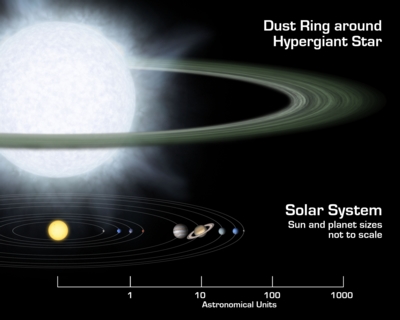

Image: This illustration compares the size of a gargantuan star and its surrounding dusty disk (top) to that of our solar system. Monstrous disks like this one were discovered around two “hypergiant” stars by NASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope. Astronomers believe these disks might contain the early “seeds” of planets or, possibly, leftover debris from planets that already formed. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/R. Hurt.

NOTE: The orbital distances in this picture are plotted on a logarithmic scale. This means that a given distance shown here represents proportionally smaller actual distances as you move to the right. The sun and planets in our solar system have been scaled up in size for better viewing.

Studied with the Spitzer Space Telescope, the two stars show dust disks that spread 60 times as far as Pluto’s orbit around the Sun, and seem to contain ten times the mass currently estimated to be in the Kuiper Belt. Are we looking at planetary formation? Joel Kastner of the Rochester Institute of Technology in New York, first author of a paper on this work that is about to appear in the Astrophysical Journal Letters, thinks the answer may well be yes. “These disks may be well-populated with comets and other larger bodies called planetesimals,” said Kastner. “They might be thought of as Kuiper Belts on steroids.”

Further evidence: the dust seems to show the presence of silicates, and the disk around R66 showed signs of dust clumping in the form of silicate crystals and larger dust grains. These are the processes astronomers believe lead to planets, but whatever worlds might form will likely have a short life. Massive stars like these burn out quickly and become supernovae, leaving little time for life to evolve. Ahead for the team is the study of new Spitzer spectra of other hypergiant stars to see how many more are circled by disks of dust.

Hmm a star that could burn the moose nugget necklace off an enviromentalist’s neck at 100 AU…… I read this and thought immediately of Campbell’s classic SF “The Mightiest Machine”.

I wonder if it will ever be possible to record full spectra from such a material ring? It would be interesting to see what the element composition would be.

Planets around bluewhite supergiants, planets in binary systems, planets around red and brown dwarf stars. All the suppositions that were declared impossible not so many years ago. Perhaps the more inventive SF writters had more on the ball than the science community would give them credit for :)

Well said! And on the subject of planetary disks, be sure to check out the Systemic site, where exoplanet-hunter Greg Laughlin has just published his thoughts on, among other things, a photograph taken by Hubble of a protostellar disk, or proplyd, in the Orion star-forming region:

http://oklo.org/?p=38

Quoting Laughlin: “From the frigid depths of the Orion proplyd, planets will eventually form. Perhaps life, and even a future alien civilization will emerge.” And that’s the kind of thing that keeps planet hunters up at night.