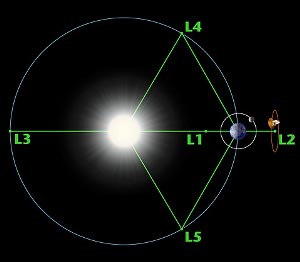

The idea that the Moon was formed through the impact of a Mars-sized object with the early Earth (the ‘big whack’) has gained credibility over the years. Call it ‘Theia,’ a hypothetical planet that may have formed in our system’s earliest era. And place it for argument’s sake at either the L4 or L5 Lagrangian point, where the gravitational influences of other developing planets like Venus may have destabilized its orbit, accounting for the subsequent impact.

It’s an interesting notion that helps us to understand why the Moon has such a small iron core. In the early Solar System, both Theia and Earth would still have been molten, so that heavier elements like iron sank into their cores. The effect of the impact, say Princeton University’s Edward Belbruno and Richard Gott, would have been to strip away primarily the lighter elements on the outer layers of the two planets, providing the building blocks for the Moon.

Image: The Lagrangian points of the Earth-Sun system (note the James Webb Space Telescope at L2). Credit: NASA.

It’s helpful that where an object forms tells us much about its characteristics. Consider water, for example, The gas and dust that gave birth to our Solar System changed as temperature varied, with the Earth at a warm 1 AU forming largely out of silicon, magnesium and iron, with enough oxygen to oxidize much of the former. Proximity to the Sun meant that the infant Earth had little water, especially compared to bodies that formed further out in the system, and volatiles like ice may have been delivered to our world by incoming objects from the outer regions of the cloud — beyond the so-called ‘snow line’ — where water is more common.

In the case of the Theia investigation, we can assume that any L4 or L5 asteroids with the same composition as the Moon and the Earth would therefore have formed in roughly the same orbital location. And evidently it is precisely in these L4 and L5 regions where Belbruno and Gott’s calculations show Theia could have grown.

How to learn more? As we’ve noted earlier in these pages, NASA’s twin Solar Terrestrial Relations Observatory (STEREO) spacecraft are about to enter the L4 and L5 regions, each 93 million miles away along Earth’s orbit. “These places may hold small asteroids, which could be leftovers from a Mars-sized planet that formed billions of years ago,” says Michael Kaiser, project scientist for STEREO at NASA GSFC. If so, STEREO’s imaging instruments may be able to spot one or more of them.

With STEREO now nearing both regions, and with both remaining in the field of view of the two craft after passage through these huge swathes of space, we have an opportunity to put the Theia theory to a useful test. Want to get involved? Anyone with an Internet connection can help in the painstaking work of spotting an asteroid as it changes position against background stars. The data can be viewed at the Sungrazing Comets site, where both STEREO and SOHO (Solar and Heliospheric Observatory) data are available for access.

I’m sure this seems like a dumb question to your readers, but I have read a few Lagrangian explanations without gaining an understanding of why the L3, L4 and L5 sites are any different than a normal orbit. The other two offer an “unnatural” orbit in that they remain inside or outside the “correct” orbit for their speed of revolution around the sun, thereby matching the Earth or Moon.

But the L3, 4, 5 all look like normal orbits for the same distance and speed as the Earth is from the Sun.

What am I missing? Wouldn’t any object anywhere along Earth’s orbital track remain in place, just as the Earth does?

Thanks for any assistance.

I would think that the solar-earth L4 and L5 points would be rather unstable in that the gravitational influences of some of the other planets would cause objects there to move around. If there are asteroids in these places (like Jupiter’s Trojan asteroids), they must be very small.

this seems like a credible theory to me. after all, the moon is a very large satellite relative to the earth. its size, mass, and gravity are similar to the large moons of the gas giants (namely jupiters galilean moons and saturns titan) which you wouldnt expect to find around a terrestrial planet.

Has anyone actually figured out how do access the data/photos for this project? I spent 20 minutes going form one page to the next and never figure out how to get the data. Very poor thinking considering they called for public help. I think they could have looked at Galaxy Zoo to see how to make a user friendly portal for a science project.

Hi Mike

The L3 position is unstable and liable to drift, but L4 & L5 are mirror images of each other and they’re stable. If an object drifted slightly away from them, the sum of forces – from the Earth, Sun and centrifugal forces – actually pushes the object back towards the L4 or L5 points. At no other L-point does that happen, which is why they’re not stable.

They’re defined mathematically by working out the effect of gravity on a small particle in the same reference frame as the Earth’s orbit. When you do that you have to take into account centrifugal force which acts to counteract the Sun’s influence somewhat. When you plot all the relevant forces points of equal force appear at the Lagrange Points, but only the L4 & L5 points have the resulting forces pointing back to them.

However if an object in the L point gets too big, about 4.5% of the Earth’s mass, then it’s gravitational attraction towards the Sun or the Earth starts to overwhelm the stabilising forces. Eventually a growing object will drift around the orbit and ultimately interact violently with the Earth – either being thrown into a new orbit or colliding. Thus what happened to Theia when it massed 10% of Earth.

How is the stability of the L4 and L5 points affected by how elliptical the orbit is?

Hi Dave

Good question. Small amounts of ellipticity don’t affect the L4 & L5 potentials very much, but high levels cause the “points” to become ellipses that lengthen as the ellipticity increases. Objects orbitting them end up doing horse-shoe orbits that oscillate from one to the other. Perturbations by other planets also produce horse-shoe orbits on objects in the L4/5 points, but the effect is stronger in highly elliptical orbits.

Hey D.M. Would those L4/5 regions with say, an extream elliptical orbit: expand and contract in volume? Sorta like – ‘breathing’ chili peppers? Or maybe the L4/5 points of a comet or something more massive? Thus causing a reduced stabillity in those regions. What, with, all the ‘breathing’ and shape shifting and such?

Thanks for the reply, Adam. I appreciate it. If I understand you correctly, there really can’t be another object sharing Earth’s orbital track. (Except the L points, for small objects.) Eventually, physics will drive both objects together or one out of the orbit.

Does the physics work quickly enough to affect a human launched mission (tens/hundreds of years versus thousands/millions)?

I don’t know about that Mike J. – Gerry Anderson said there was

another Earth on the exact opposite side of the Sun in 1969:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Journey_to_the_Far_Side_of_the_Sun

There was also a TV film made circa 1972 that was a pilot for a

series that never happened with a similar premise of a parallel

Earth on the other side of our star and what happens when an

astronaut from our world crash lands there.

I recall one of the differences was that this parallel world had

three moons among other things that became apparent once the

astronaut realized he was not on his planet of origin. Anyone

remember the title?

Sorry, no joy on the TV series, but I found the link interesting.

I also remember the TV pilot but unfortunately not the title. Besides the borrowing from the movie, it had some “1984” elements as well.

OK, here it is. I just Googled “parallel earth tv movie” and it popped right up:

http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0070742/

“The Stranger”, made in 1973 according to the link.

May 20, 2009

A Benevolent Sort of Asteroid Bombardment?

Written by Anne Minard

Celestial impacts can bring life as well as wipe it out, say the authors of a new study out of the University of Colorado at Boulder.

A case in point: the bombardment of Earth nearly 4 billion years ago by asteroids as large as Kansas would not have had the firepower to extinguish potential early life on the planet and may even have given it a boost.

In a new paper in the journal Nature, Oleg Abramov and Stephen Mojzsis report on their study of impact evidence from lunar samples, meteorites and the pockmarked surfaces of the inner planets. The evidence paints a picture of a violent environment in the solar system during the Hadean Eon 4.5 to 3.8 billion years ago, particularly through a cataclysmic event known as the Late Heavy Bombardment about 3.9 million years ago.

Although many believe the bombardment would have sterilized Earth, the new study shows it would have melted only a fraction of Earth’s crust, and that microbes could well have survived in subsurface habitats, insulated from the destruction.

“These new results push back the possible beginnings of life on Earth to well before the bombardment period 3.9 billion years ago,” Abramov said. “It opens up the possibility that life emerged as far back as 4.4 billion years ago, about the time the first oceans are thought to have formed.”

Full article here:

http://www.universetoday.com/2009/05/20/a-benevolent-sort-of-asteroid-bombardment/

Needless to say, this is good news for the chances of life appearing and surviving

on other planets throughout the Universe. Whether they eventually evolve enough

to create their own version of the Internet is another matter.

What happened to Theia after the collision?