Whenever I hear the word ‘serendipity,’ I think of my old mentor Norman Eliason, professor of medieval studies at UNC-Chapel Hill. During my years of grad work, Dr. Eliason passed along habits of precision and an eye for detail that I’ve tried, not always successfully, to emulate. One day when he asked about my work habits, I told him that I preferred to work outside the library, checking out books I needed or making copies of relevant journal articles.

I can still see him nodding slowly in his office chair, cigarette protruding from his hand, and I knew I’d said the wrong thing. “You need to be among the books,” he said. “Use your free time to look around and you’ll run into things in the stacks you never knew were there.” I took his advice and he was right. Serendipity –chance discovery, usually when looking for something else — worked. At least, it always has for me, but you have to put yourself in a place where discoveries are likely to be made.

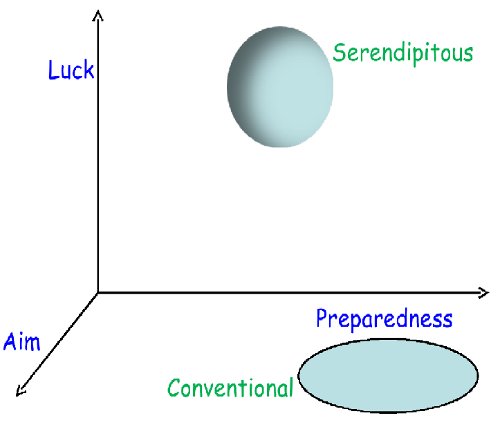

Image: Serendipitous discoveries combine luck (or chance), preparedness and aim. Conventional school science is usually concentrated on the preparedness, aim plane and totally new things are found on the preparedness, luck plane. There is usually, however, some aim to the observations, which is why I have tried through shading to make the region have volume. Credit (image and caption): A.C. Fabian.

‘Chance or unplanned discovery’ is how Andrew Fabian (University of Cambridge) defines serendipity, but I always add in a notion of good fortune. To me, serendipity means not only making an unexpected find, but making one that materially advances an investigation. Fabian probably wouldn’t disagree, based on the recent paper he wrote on the subject of serendipity in astronomy. Consider:

In contrast with school laboratory science where the aim is to plan and carry out an experiment in controlled conditions, in general astronomers cannot do this and must rely on finding something or a situation which suits. Often, the possibilities afforded by a phenomenon are only appreciated later, after the surprise of the discovery has worn off.

Fabian also quotes Pasteur’s famous “Chance favors the prepared mind.” In any case, we find by looking at examples of serendipity in astronomy that such discoveries often push our thinking into new areas. Fabian also notes the tension inherent in this process, contrasting a ‘fishing expedition’ against the tight methodology that science prefers. This is probably because serendipity seems entirely random, but its history of discovery is robust.

Some cases:

- Jocelyn Bell and team were looking for so-called ‘radio stars’ in the late 1960s and ran into 1.3-second pulses that led to the discovery of pulsars. Interestingly, earlier data also showed these pulses but were not analyzed sufficiently to reveal them.

- Gamma-ray bursts (GRBs) were discovered by US military satellites in the 1960s engaged in surveillance of Soviet military activity.

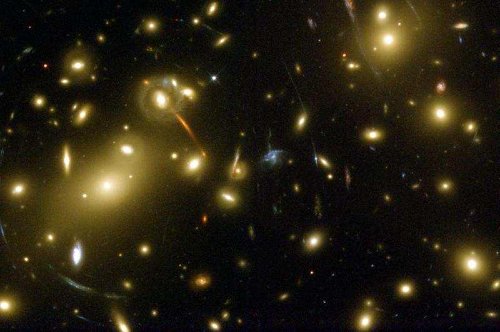

- A ‘double quasar’ discovered in 1979 turned out to be the gravitationally-lensed image of the same background object. The team investigating the image were making routine quasar measurements of a large number of quasars. Again, images like this one, and many later lensed objects, had been seen and published but not previously noticed as double images, nor their nature understood.

Image: A foreground galactic cluser whose total mass is gravitationally bending the light from distant galaxies into many arcs. How many such images were catalogued before gravitational lensing of galactic objects was understood? Credit: A.C. Fabian.

In the cases Fabian is most interested in, people looking for one thing ran into quite another. He runs through other cases of unexpected discovery, making the reader wonder how many significant things are waiting to be found in data already on our hard disks and even locked up in old astronomical images. Who knows what mysteries might still unfold from a decades old Palomar photograph?

Fabian wonders whether there is a way to turn serendipity into a tool that can facilitate further discovery:

Does it not then make sense to tailor our research funding, both for the hardware – the telescopes – and for the modes of working, to take [serendipity] into account? This leads to a current dilemma. Facilities (and people) are increasingly expensive. Funding agencies using public funds want value for money so are most likely to fund projects and telescopes and teams where a successful outcome is predicted. This tends to mean looking into areas close to where we know, rather than stepping out into the unknown. In the case of serendipitous discovery there is little that can be predicted with certainty, we can only argue on the basis of past success. It means stepping out boldly in discovery space.

He goes on to argue in this paper that direct approaches to fundamental problems may sometimes make us too narrow in our investigation. Recalling that a good view of many celestial objects comes with averted vision rather than direct focus, he champions ‘general astronomical observatories of all wavebands’ as the best way to target the unexpected, adding:

It is ironic that our telescopes are remembered mostly for the serendipitous discoveries they made… and not for the issues for which the original science case was made, yet we put most of our efforts into the known science aspects of the science case for a new telescope. Rather like the common view of democracy, or peer review, this common approach is highly flawed but is however the best available.

I take this to mean that there may be no way to channel serendipity, but we should not forget the role it has played in past discovery. Fabian can cite examples from the Keck telescopes ranging from studies of Type I supernovae and the accelerating universe to the discovery of Pluto-sized dwarf planets. The paper is an intriguing survey of the chance element in discovery and one that emphasizes the importance of both preparation and openness to the unknown.

The paper is Fabian, “Serendipity in Astronomy,” to be published in Serendipity and available online.

One approach to serendipity might be saving as much raw data as possible from every instrument, even if much of it is not needed by the nominal project the instrument was built for. I recall reading about a situation where a scientist wanted to analyze seisomograph data to look for an effect, but found out the existing data was useless because the effect he was looking for was filtered out when the data was processed for conventional analysis. It’s hard to justify building expensive devices without specific achievable goals, but at least we could try build them in ways that allow for things we didn’t think of.

That’s all very well, but surely there’s the problem of cost involved? A targeted search is always going to be cheaper to build telescopes and missions for than general surveys that try to cover more sky and wavelengths to the same sensitivity. Fabian does touch on the problem of getting funding for something that only *might* discover something of interest as opposed to specified goals with a reasonable chance of increasing our knowledge about a specific aspect of the universe.

To be honest, having skimmed through the paper, I’m not entirely sure what his point is apart from “do more observing at more wavelengths.” That’s very nice in principle, but what practical steps should be taken to acheive that goal? There are any number of survey-type projects going on — the Sloan Digital Sky Survey and the All Sky Optical SETI Survey, for example. Is it worth funding this efforts with bigger and better equipment? What about putting money into investigating tweaks to telescope design and operations to make them and the data they produce more open to serendipitous discoveries?

And surely serendipity already has its place in mission and telescope proposals? I am sure the mission proposals for COROT and Kepler must be chock full of examples of what they might discover about variable stars, eclipsing binaries, and all kinds of other stellar phenomena in addition to finding extra-solar planets. The longer the list of “piggy-back” ideas, the greater the chances of serendipitous discoveries, and I would be extremely surprised if that didn’t factor into the decisions of the bean-counters at NASA and elsewhere at least to some extent.

Finally, I’m not sure that a more general approach to observing (if that’s the right term for it) would help find as many serendipitous discoveries as one might thing. Collecting the data is just the start — and it would certainly pile up the data, to–ahem–astronomical proportions. But someone still has to have the willingness, know how, funding, and–yes–inspiration to look in the right places and analyze the data in just the right way to dig out that unexpected result. With missions as they are currently design, the dataset is necessarily more limited and anomalies and unexpected events that lead to serendipitous (boy I am glad Firefox has a spellchecker!) discoveries are thus more likely to jump out of the data.

Anyway, the paper certainly got the thought-processes stirring, and that’s always a good thing, but I hope there is more to it than that. Perhaps follow-up papers are in the works to help spell out some concrete ideas in more detail?

tacitus wrote:

Don’t know about follow-ups, but I liked the paper because it reminded me how often discoveries come about when we’re looking for something entirely different. Another way of saying that the universe continues to surprise us, which says something about the completeness of our knowledge in any particular era. Like you, I’d like to see Fabian go further with this.

NS wrote:

Yes, and this goal is more and more feasible given how plentiful and cheap digital storage has become.

There’s the Roman proverb: ‘fortis fortuna adjuvat’ ‘Fortune favors the resolute’ is the way I’d translate it. ‘fortis’ as strong, brave, resolute. (It’s the -is accusative plural of the adjective which point of grammar I add for the classical astronomers who visit this site). What a marvelous entry, Paul.

Also reminiscent of our friend Pliny the Elder, Barney, with his vita vigilia est! Roughly translated as ‘being alive is being awake.’ In any case, put yourself in the right place with the right frame of mind and things happen.

Know the old joke about the drunk and the lost keys? A policeman finds a guy scrabbling under a lamp-post and asks him what he’s doing. “Looking for my keys,” he replies. “Is this where you dropped them?” asks the cop. “No,” replies the drunk, “but here I can see what I’m doing.”

This encapsulates much of narrowly targeted research, in terms of both mindset — and results. Serendipitous discoveries that come from having an alert and curious mind, and actually looking at what you see, also hold sway in biology, starting with Fleming’s penicillin. Targeted research has yielded incredibly low returns. One of the best pieces of information about cancer came from looking at a lowly aquatic ciliate called Tetrahymena, in which they first discovered telomerase; another from viral insertions that led to the identification of oncogenes. And the knowledge that helped us understand and combat HIV came from retroviruses, that were deemed incredibly exotic. I could list many more examples, but you get the gist.

THREE PRINCIPLES OF SERENDIP: INSIGHT, CHANCE, AND DISCOVERY IN QUALITATIVE RESEARCH

by Gary Fine and James Deegan

This article discusses the role of serendipity in qualitative research. Drawing on ideas and methodological suggestions from a set of classic and recent fieldwork accounts, the authors examine conceptions of serendipity and the ways that these conceptions become embedded in the processes by which we incorporate and embrace the temporal, relational, and analytical aspects of serendipity.

The authors reject the perspective that it is the divine roll of the dice that determines serendipity and argue that serendipity is the interactive outcome of unique and contingent “mixes” of insight coupled with chance. A wide range of attempts to make sense of serendipity in sociology and anthropology are provided as exemplars of how planned insights coupled with unplanned events can potentially yield meaningful and interesting discovery in qualitative research.

Introduction

Three goodly young princes were traveling the world in hopes of being educated to take their proper position upon their return. On their journey they happened upon a camel driver who inquired if they had seen his missing camel. As sport, they claimed to have seen the camel, reporting correctly that the camel was blind in one eye, missing a tooth, and lame. From these accurate details, the owner assumed that the three had surely stolen the camel, and they were subsequently thrown into jail.

Soon the wayward camel was discovered, and the princes brought to the perplexed Emperor of the land, who inquired of them how they had learned these facts. That the grass was eaten on one side of the road suggested that camel had one eye, the cuds of grass on the ground indicated a tooth gap, and the traces of a dragged hoof revealed the camel’s lameness. (Adapted from The Peregrinaggio [1557] in Remer, 1965)

Full article (with references) here:

http://philosophyofscienceportal.blogspot.com/2009/09/serendipity-again.html

I agree with serendipity. Ive found a few of my favorite books by perusing the stacks in my college library.

The universe especially has much to offer.. and while directed searches are important, we cant get tunnel vision when observing the skies.