Centauri Dreams

Imagining and Planning Interstellar Exploration

To the Stars with Human Crews?

How long before we can send humans to another star system? Ask people active in the interstellar community and you’ll get answers ranging from ‘at least a century’ to ‘never.’ I’m inclined toward a view nudging into the ‘never’ camp but not quite getting there. In other words, I think the advantages of highly intelligent instrumented payloads will always be apparent for missions of this duration, but I know human nature well enough to believe that somehow, sometime, a few hardy adventurers will find a way to make the journey. I do doubt that it will ever become commonplace.

You may well disagree, and I hope you’re right, as the scenarios open to humans with a galaxy stuffed with planets to experience are stunning. Having come into the field steeped in the papers and books of Robert Forward, I’ve always been partial to sail technologies and love the brazen, crazy extrapolation of Forward’s “Flight of the Dragonfly,” which appeared in Analog in 1982 and which would later be turned into the novel Rocheworld (Baen, 1990). This is the novel where Forward not only finds a bizarre way to keep a human crew sane through a multi-decade journey but also posits a segmented lightsail to get the crew home.

Image: The extraordinary Robert Forward, whose first edition of Flight of the Dragonfly was expanded a bit from the magazine serial and offered in book form in 1984. The book would later be revised and expanded further into the 1990 Baen title Rocheworld. The publishing history of this volume is almost as complex as the methods Forward used to get his crew back from Barnard’s Star!

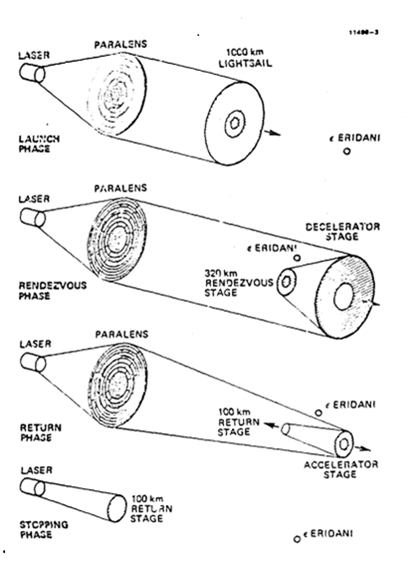

Forward was a treasure. Like Freeman Dyson, his imagination was boundless. Whether we would ever choose to build the vast Fresnel lens he posited in the outer Solar System as a way of collimating a laser beam from near-Sol orbit, and whether we could ever use that beam to reflect off detached segments of the sail upon arrival to slow it down are matters that challenge all boundaries of engineering. I can hear Forward chuckling. Here’s the basic idea, as drawn from his original paper on the concept.

Image: Forward’s separable sail concept used for deceleration, from his paper “Roundtrip Interstellar Travel Using Laser-Pushed Lightsails,” Journal of Spacecraft and Rockets 21 (1984), pp. 187-195. The ‘paralens’ in the image is a huge Fresnel lens made of concentric rings of lightweight, transparent material, with free space between the rings and spars to hold the vast structure together, all of this located between the orbits of Saturn and Uranus. Study the diagram and you’ll see that the sail has three ring segments, each of them separating to provide a separate source of braking or acceleration for the arrival, respectively, and departure of the crew. Imagine the laser targeting this would require. Credit: Robert Forward.

I tend to think that Les Johnson is right about sails as they fit into the interstellar picture. In a recent interview with a publication called The National, Johnson (NASA MSFC) made the case that we might well reach another star with a sail driven by a laser. Breakthrough Starshot, indeed, continues to study exactly that concept, using a robotic payload miniaturized for the journey and sent in swarms of relatively small sails driven by an Earth-based laser. But when it comes to human missions to even nearby stars, Johnson is more circumspect. Let me quote him on this from the article:

“As for humans, that’s a lot more complicated because it takes a lot of mass to keep a group of humans alive for a decade-to centuries-long space journey and that means a massive ship. For a human crewed ship, we will need fusion propulsion at a minimum and antimatter as the ideal. While we know these are physically possible, the technology level needed for interstellar travel seems very far away – perhaps 100 to 200 years in the future.”

Johnson’s background in sail technologies for both near and deep space at Marshall Space Flight Center is extensive. Indeed, there was a time when his business card described him as ‘Manager of Interstellar Propulsion Technology Research’ (he once told me it was “the coolest business card ever”). He has also authored (with Gregory Matloff and Giovanni Vulpetti), books like Solar Sails: A Novel Approach to Interstellar Travel (Springer, 2014) and A Traveler’s Guide to the Stars (Princeton University Press, 2022), as well as editing the recent Interstellar Travel: Purpose and Motivations (Elsevier, 2023). In addition to that, his science fiction novels have explored numerous deep space scenarios.

Image: NASA’s Les Johnson, a prolific author and specialist in sail technologies. Credit: NASA.

So there’s a much more optimistic take on the human interstellar guideline than the one I gave in my first paragraph, and of course I hope it’s on target. We’re probably not going to be going to what is sometimes called an “Earth 2.0,” in Johnson’s view, because he doubts there are any such reasonably close to us. That’s something we’ll be learning a great deal more about as future space instrumentation comes online, but we can bear in mind that the explorers who tackled the Pacific in the great era of sail didn’t set out thinking they were going to find another Europe, either. The point is to explore and to learn what you can, with all the unexpected benefits that brings.

Johnson’s early interest in sails, by the way, was fired not so much by Forward’s Rocheworld as by Larry Niven and Jerry Pournelle’s novel The Mote in God’s Eye (Simon & Schuster, 1974), where an incoming laser sail from another civilization is detected. The realization that unusual astronomical observations point to a technology, and a laser-beaming one at that, is an exciting part of the book. Here the authors’ human starship crew describes the detection of a strange light emanating from a smaller star (the Mote) in front of a much larger supergiant (the Eye):

“…I checked with Commander Sinclair. He says his grandfather told him the Mote was once brighter than Murcheson’s Eye, and bright green. And the way Gavin’s describing that holo – well, sir, stars don’t radiate all one color. So -”

“All the more reason to think the holo was retouched. But it is funny, with that intruder coming straight out of the Mote…”

“Light,” Potter said firmly.

“Light sail!” Rod shouted in sudden realization…”

For more on all this, see my Our View of a Decelerating Magsail in these pages. It’s not surprising that Niven and Pournelle ran their lightsail concept past Robert Forward at a time when the idea was just gaining traction. We all have career-changing literary experiences. I can remember how a childhood reading of Poul Anderson’s The Enemy Stars (J.B. Lippincott, 1959) utterly fired my imagination toward the idea of leaving the Solar System entirely. It was a finalist for the Hugo Award that year following serialization in Astounding, though I didn’t encounter it until later.

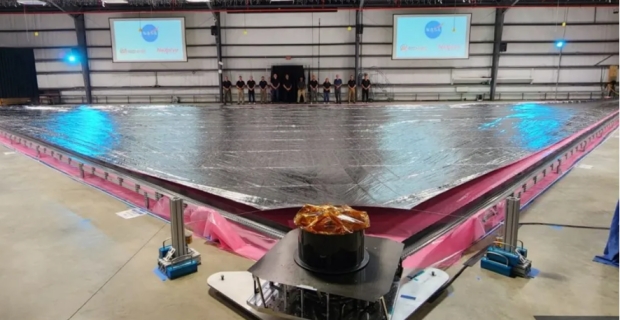

Johnson’s work at Marshall Space Flight Center takes in the deployment of a large solar sail quadrant for the Solar Cruiser mission that was first unfurled in 2022 to demonstrate TRL 5 capability, and has just been deployed at contractor Redwire Corp.’s facility in Longmont, Colorado to demonstrate TRL 6. In NASA’s terms, that means going from “Component or breadboard validation in relevant environment” (TRL 5) to “System or subsystem model or prototype demonstration in a relevant environment (ground or space).” In other words, this is progress. At TRL 6, a system is considered “a fully functional prototype or representational model.” Says Johnson in a recent email:

“25 years ago, when I first met Dr. Forward, he inspired me to plan a development program for solar sails that would eventually lead us to the stars. With Bob’s help, I laid out a milestone driven roadmap that began with the space flight of a 10 m² solar sail, which we did in 2010 with NanoSail-D.

“Next on the plan was the development of something an order of magnitude larger. This was achieved with the development and launch of the 86 m² Near Earth Asteroid Scout solar sail in 2022 and the soon to be launched ACS-3 sail. The Solar Cruiser sail is an order of magnitude larger still at 1653 Square meters. The next step is 10,000!”

Image: NASA and industry partners used two 100-foot lightweight composite booms to unfurl the 4,300-square-foot sail quadrant for the first time Oct. 13, 2022, at Marshall Space Flight Center, making it the largest solar sail quadrant ever deployed at the time. On Jan. 30, 2024, NASA cleared a key technology milestone, demonstrating TRL6 capability at Redwire’s new facility in Longmont, Colorado, with the successful deployment of one of four identical solar sail quadrants. Credit: NASA (although I’ve edited the caption slightly to reflect the TRL level reached).

Solar sails are becoming viable choices for space missions, and the Breakthrough Starshot investigations remind us that sails driven not just by sunlight but by lasers are within the bounds of physics. A key question that will be informed by our experience with solar sails is how laser-driven techniques scale. Theoretically, they seem to scale quite well. Are the huge structures Forward once wrote about remotely feasible (perhaps via nanotech construction methods), or is Johnson right that fusion and one day antimatter may be necessary for craft large enough (and fast enough) to carry human crews?

Otto Struve: A Prescient Look at Exoplanet Detection

Some things just run in families. If you look into the life of Otto Struve, you’ll find that the Russian-born astronomer was the great grandson of Friedrich Georg Wilhelm von Struve, who was himself an astronomer known for his work on binary stars in the 19th Century. Otto’s father was an astronomer as well, as was his grandfather. That’s a lot of familial energy packed into the study of the stars, and the Struve of most recent fame (Otto died in 1963) drew on that energy to produce hundreds of scientific papers. Interestingly, the man who was director at Yerkes and the NRAO observatories was also an early SETI advocate who thought intelligence was rife in the Milky Way.

Of Baltic-German descent, Otto Struve might well have become the first person to discover an exoplanet, and therein hangs a tale. Poking around in the history of these matters, I ran into a paper that ran in 1952 in a publication called The Observatory titled “Proposal for a Project of High-Resolution Stellar Radial Velocity Work.” Then at UC Berkeley, Struve had written his PhD thesis on the spectroscopy of double star systems at the University of Chicago, so his paper might have carried more clout than it did. On the other hand, Struve was truly pushing the limits.

Image: Astronomer Otto Struve (1897-1963). Credit: Institute of Astronomy, Kharkiv National University.

For Struve was arguing that Doppler measurements – measuring the wavelength of light as a star moves toward and then away from the observer – might detect exoplanets, if they existed, a subject that was wildly speculative in that era. He was also saying that the kind of planet that could be detected this way would be as massive as Jupiter but in a tight orbit. I can’t call this a prediction of the existence of ‘hot Jupiters’ as much as a recognition that only that kind of planet would be available to the apparatus of the time. And in 1952, the idea of a Jupiter-class planet in that kind of orbit must have seemed like pure science fiction. And yet here was Struve:

…our hypothetical planet would have a velocity of roughly 200 km/sec. If the mass of this planet were equal to that of Jupiter, it would cause the observed radial velocity of the parent star to oscillate with a range of ± 0.2 km/sec—a quantity that might be just detectable with the most powerful Coudé spectrographs in existence. A planet ten times the mass of Jupiter would be very easy to detect, since it would cause the observed radial velocity of the star to oscillate with ± 2 km/sec. This is correct only for those orbits whose inclinations are 90°. But even for more moderate inclinations it should be possible, without much difficulty, to discover planets of 10 times the mass of Jupiter by the Doppler effect.

Struve suggested that binary stars would be a fertile hunting ground, for the radial velocity of the companion star would provide a “reliable standard of velocity.”

Imagine what would have happened if the discovery of 51 Pegasi (the work of Michel Mayor and Didier Queloz in 1995) had occurred in the early 1960s, when it was surely technically possible. Joshua Winn (Princeton University) speculates about this in his book The Little Book of Exoplanets (Princeton University Press, 2023). And if you start going down that road, you quickly run into another name that I only recently discovered, that of Kaj Aage Gunnar Strand (1907-2000). Working at Sproul Observatory (Swarthmore College) Strand announced that he had actually discovered a planet orbiting 61 Cygni in 1943. Struve considered this a confirmed exoplanet.

Now we’re getting deep into the weeds. Strand was using photometry, as reported in his paper “61 Cygni as a Triple System.” In other words, he was comparing the positions of the stars in the 61 Cygni binary system to demonstrate that they were changing over time in a cycle that showed the presence of an unseen companion. Here I’m dipping into the excellent Pipettepen site at the University of North Carolina, where Mackenna Wood has written up Strand’s work. And as Wood notes, Strand was limited to using glass photographic plates and a ruler to make measurements between the stars. Here’s the illustration Wood ran showing how tricky this would have been:

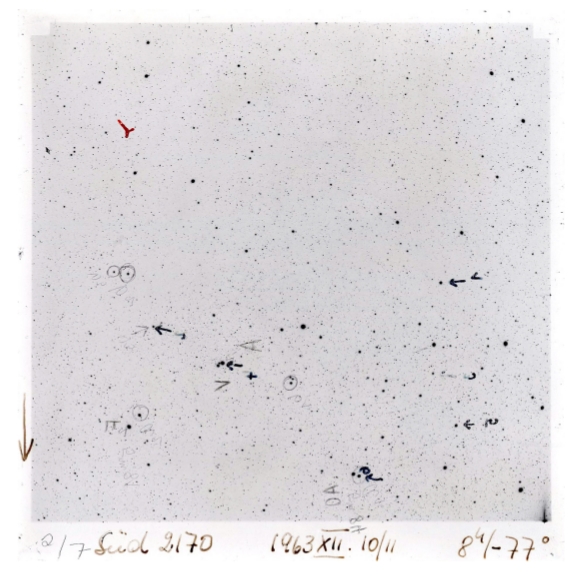

Image: An example of a photographic plate from one of the telescopes used in the 1943 61 Cygni study. The plate is a negative, showing stars as black dots, and empty space in white. Brighter stars appear as larger dots. Written at the bottom of the plate are notes indicating when the image was taken (Nov. 10, 1963), and what part of the sky it shows. Credit: Mackenna Wood.

Strand’s detection is no longer considered valid because more recent papers using more precise astrometry have found no evidence for a companion in this system. And that was a disappointment for readers of Arthur C. Clarke, who in his hugely exciting The Challenge of the Spaceship (1946) had made this statement in reference to Strand: “The first discovery of planets revolving around other suns, which was made in the United States in 1942, has changed all ideas of the plurality of worlds.”

Can you imagine the thrill that would have run up the spine of a science fiction fan in the late 1940s when he or she read that? Someone steeped in Heinlein, Asimov and van Vogt, with copies of Astounding available every month on the newsstand and the great 1950s era of science fiction about to begin, now reading about an actual planet around another star? I have a lot of issues of Astounding from the late 1930s in my collection though few from the late ‘40s, but I plan to check on Strand’s work to see if it appeared in any fashion in John Campbell’s great magazine in the following decade. Surely there would have been a buzz at least in the letter columns.

Image: Kaj Aage Gunnar Strand (1907-2000) was director of the U.S. Naval Observatory from 1963 to 1977. He specialized in astrometry, especially work on double stars and stellar distances. Credit: Wikimedia Commons / US Navy.

We’re not through with early exoplanet detection yet, though, and we’re staying at the same Sproul Observatory where Strand did the 61 Cygni work. It was in 1960 that another Sproul astronomer, Sarah Lippincott, published work arguing that Lalande 21185 (Gliese 411) had an unseen companion, a gas giant of ten Jupiter masses. A red dwarf at 8.3 light years out, this star is actually bright enough to be seen with even a small telescope. And in fact it does have two known planets and another candidate world, the innermost orbiting in a scant twelve days with a mass close to three times that of Earth, and the second on a 2800-day orbit and a mass fourteen times that of Earth. The candidate planet, if confirmed, would orbit between these two.

Image: Swarthmore College’s Sarah Lippincott, whose work on astrometry is highly regarded, although her exoplanet finds were compromised by faulty equipment. Credit: Swarthmore College.

The work on Lalande 21185 in exoplanet terms goes back to Peter van de Kamp, who proposed a massive gas giant there in 1945. Lippincott was actually one of van de Kamp’s students, and the duo used astrometrical techniques to study photographic plates taken at Sproul. It turns out that Sproul photographic plates taken at the same time as those Lippincott used in her later paper on the star were later used by van de Kamp in his claim of a planetary system at Barnard’s Star. It was demonstrated later that the photographic plates deployed in both studies were flawed. Systematic errors in the calibration of the telescope were the culprit in the mistaken identifications.

Image: Astronomer Peter van de Kamp (1901-1995). Credit: Rochester Institute of Technology newsletter.

We always knew that exoplanet hunting would push us to the limits, and today’s bounty of thousands of new worlds should remind us of how the landscape looked 75 years ago when Otto Struve delved into detection techniques using the Doppler method. At that time, as far as he knew, there was only one detected exoplanet, and that was Strand’s detection, which as we saw turned out to be false. But Struve had the method down if hot Jupiters existed, and of course they do. He also reminded us of something else, that a large enough planet seen at the right angle to its star should throw a signal:

There would, of course, also be eclipses. Assuming that the mean density of the planet is five times that of the star (which may be optimistic for such a large planet) the projected eclipsed area is about 1/50th of that of the star, and the loss of light in stellar magnitudes is about 0.02. This, too, should be ascertainable by modern photoelectric methods, though the spectrographic test would probably be more accurate. The advantage of the photometric procedure would be its fainter limiting magnitude compared to that of the high-dispersion spectrographic technique.

There, of course, is the transit method which has proven so critical in fleshing out our catalogs of exoplanets. Both radial velocity and transit techniques would prove far more amenable to early exoplanet detection than astrometry of the sort that van de Kamp and Lippincott used, though astrometry definitely has its place in the modern pantheon of detection methods. Back in 1963, when van de Kamp announced the discovery of what he thought were planets at Barnard’s Star, he relied on almost half a century of telescope observations to build his case. No one could fault his effort, and what a shame it is that the astronomer died just months before the discovery of 51 Pegasi b. It would be fascinating to have his take on all that has happened since.

What We Know Now about TRAPPIST-1 (and what we don’t)

Our recent conversations about the likelihood of life elsewhere in the universe emphasize how early in the search we are. Consider recent work on TRAPPIST-1, which draws on JWST data to tell us more about the nature of the seven planets there. On the surface, this seven-planet system around a nearby M-dwarf all but shouts for attention, given that we have three planets in the habitable zone, all of them of terrestrial size, as indeed are all the planets in the system. Moreover, as an ultracool dwarf star, the primary is both tiny and bright in the infrared, just the thing for an instrument like the James Webb Space Telescope to harvest solid data on planetary atmospheres.

This is a system, in other words, ripe for atmospheric and perhaps astrobiological investigation, and Michaël Gillon (University of Liége), the key player in discovering its complexities, points in a new paper to how much we’ve already learned. If its star is ultracool, the planetary system at TRAPPIST-1 can also be considered ‘ultracompact’ in that the innermost and outermost planets orbit at 0.01 and 0.06 AU respectively. By comparison, Mercury orbits at 0.4 AU from our Sun. The stability of the system through mean motion resonances means that we’re able to deduce tight limits on mass and density, which in turn give us useful insights into their composition.

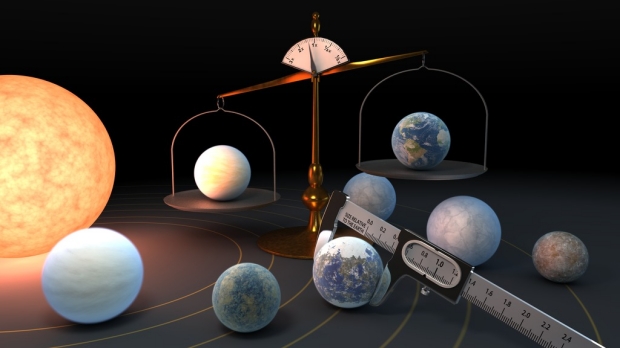

Image: Measuring the mass and diameter of a planet reveals its density, which can give scientists clues about its composition. Scientists now know the density of the seven TRAPPIST-1 planets with a higher precision than any other planets in the universe, other than those in our own solar system. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/R. Hurt (IPAC).

Because we’ve been talking about SETI recently, I’ll mention that the SETI Institute has already subjected TRAPPIST-1 to a search using the Allen Telescope Array at frequencies of 2.84 and 8.2 gigahertz. The choice of frequencies was dictated by the researchers’ interest in whether a system this compact might have a civilization that had spread between two or more worlds. Searching for powerful broadband communications when planetary alignments between two habitable planets occur as viewed from Earth is thus a hopeful strategy, and as is obvious, the search yielded nothing unusual. A broader question is whether life might spread between such worlds through impacts and subsequent contamination.

What I’m angling for here is the relationship between a bold, unlikely observing strategy and a more orthodox study of planetary atmospheres. Both of these are ongoing, with the investigation of biosignatures a hot topic as we work with JWST but also plan for subsequent space telescopes like the Habitable Exoplanet Observatory (HabEx). The gap in expectations between SETI at TRAPPIST-1 and atmosphere characterization via such instruments highlights what a shot in the dark SETI can be. But it’s a useful shot in the dark. We need to know that there is a ‘great silence’ and continue to poke into it even as we explore the likelihood of abiogenesis elsewhere.

But back to the Gillon paper. Here you’ll find the latest results on planetary dynamics at TRAPPIST-1 and the implications for how these worlds form, along with current data on their densities and compositions. Another benefit of the compact nature of this system is that the planets interact with each other, which means we get strong signals from Transit Timing Variations that help constrain the orbits and masses involved. No other system has rocky exoplanets with such tight density measurements. The three inner planets are irradiated beyond the runaway greenhouse limit, and recent work points to the two inner planets being totally desiccated, with volatiles likely in the outer worlds.

What we’d like to know is whether, given that habitable zone planets are found in M-dwarf systems (Proxima Centauri is an obvious further example), such worlds can maintain a significant atmosphere given irradiation from the parent star. This is tricky work. There are models of the early Earth that involve massive volatile losses, and yet today’s Earth is obviously life supporting. Is there a possibility that rocky planets around M-dwarfs could begin with a high volatile content to counterbalance erosion from stellar bombardment? Gillon sees TRAPPIST-1 as an ideal laboratory to pursue such investigations, one with implications for M-dwarfs throughout the galaxy. From the paper:

Indeed, its planets have an irradiation range similar to the inner solar system and encompassing the inner and outer limits of its circumstellar habitable zone, with planet b and h receiving from their star about 4.2 and 0.15 times the energy received by the Earth from the Sun per second, respectively. Detecting an atmosphere around any of these 7 planets and measuring its composition would be of fundamental importance to constrain our atmospheric evolution and escape models, and, more broadly, to determine if low-mass M-dwarfs, the larger reservoir of terrestrial planets in the Universe, could truly host habitable worlds.

Image: Belgian astronomer Michaël Gillon, who discovered the planetary system at TRAPPIST-1. Credit: University of Liége.

Thus the early work on TRAPPIST-1 atmospheres, conducted with Hubble data and sufficient to rule out the presence of cloud-free hydrogen-dominated atmospheres for all the planets in the system. But now we have early papers using JWST data, and the issues become more stark when we turn to work performed by Gwenaël Van Looveren (University of Vienna) and colleagues. While previous studies of the system have indicated no thick atmospheres on the two innermost planets (b and c), the Van Looveren team focuses specifically on thermal losses occurring as the atmosphere heats as opposed to hard to measure non-thermal processes like stellar winds.

Here the situation clarifies. Working with computer code called Kompot, which calculates the thermo-chemical structure of an upper atmosphere, the team has analyzed the highly irradiated TRAPPIST-1 environment, modeling over 500 photochemical reactions in light of X-Ray, ultraviolet and infrared radiation, among other factors. The results show strong atmospheric loss in the early era of system development, but take into account losses through the different stages of the system’s evolution. It’s important to keep in mind that a star like this takes between 1 and 2 billion years to settle onto the main sequence, a period of high radiation. It’s also true that even main-sequence M-dwarfs can show high levels of radiation activity.

The upshot: X-ray and UV activity declines very slowly in the first several billion years on the main sequence, and stellar radiation in these wavelengths is the main driver of atmospheric loss. Things look dicey for atmospheres on any of the TRAPPIST-1 planets, and the Van Looveren model generalizes to other stars. From the paper:

The results of our models tentatively indicate that the habitable zone of M dwarfs after their arrival on the main sequence is not suited for the long-term survival of secondary atmospheres around planets of the considered planetary masses owing to the high ratio of spectral irradiance of XUV to optical/infrared radiation over a very long time compared to more massive stars. Maintaining atmospheres on planets like this requires their continual replenishment or their formation very late in the evolution of the planets. A further expansion of the grid and more detailed studies of the parameter space are required to draw definitive conclusions for the entire spectral class of M dwarfs.

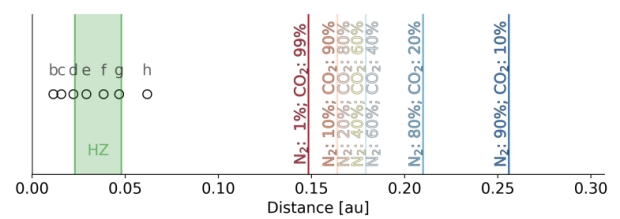

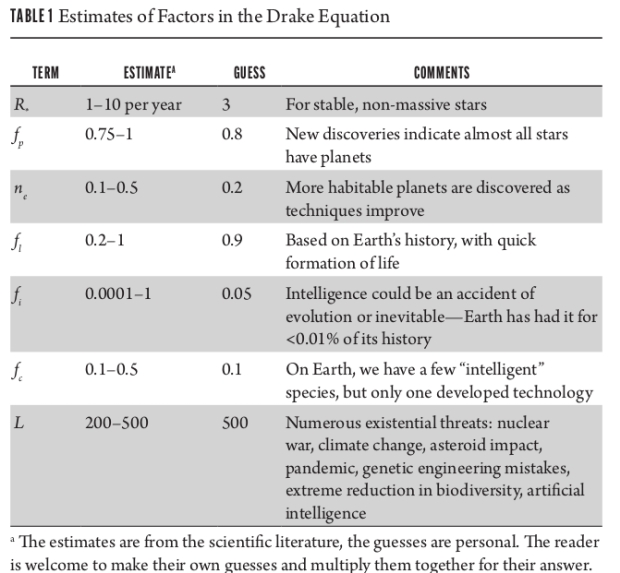

Image: This is Figure 8 from the paper. Caption: Overview of the planets in the TRAPPIST-1 system and the estimated habitable zone (indicated by the green lines, taken from Bolmont et al. 2017). We added vertical lines at the minimum distances at which atmospheres of various compositions could survive for more than 1 Gyr. Credit: Van Looveren et al.

Note the term ‘primary atmosphere.’ Primary atmospheres of hydrogen and helium give way to secondary atmospheres that are the result of later processes like volcanic outgassing and molecules breaking down under stellar radiation on the planet’s surface. The paper, then, is saying that the kind of secondary atmospheres in which we might hope to find life are unlikely to survive in this environment, although active processes on a given planet might still allow them. The paper ends this way:

Our conclusion from this work is therefore significant for terrestrial planets with a mass that is similar to the Earth’s mass that orbit mid- to late-M dwarfs such as TRAPPIST-1 near or inside the (final) habitable zone. For these planets, substantial N2/CO2 atmospheres are unlikely unless atmospheric gas is continually replenished at high rates on timescales of no more than a few million years (the loss timescales estimated in our work), for example, through volcanism.

I wouldn’t call this the death knell for atmospheric survival at TRAPPIST-1, nor do the authors, but the work points to the factors that have to be addressed in further study of the system, and the results certainly challenge the possibility of life-sustaining atmospheres on any of these planets. The Van Looveren work isn’t included in Michaël Gillon’s paper, which appeared just before its release, but I hope you’ll look at both and keep the Gillon available as the best current overview of TRAPPIST-1.

As to M-dwarf prospects in general, it’s one thing to imagine a high-radiation environment, with the possibilities that life might find an evolutionary path forward, but quite another to strip a planet of its atmosphere altogether. If that is the prospect, then the census of ‘habitable’ worlds drops sharply, for M-dwarfs make up somewhere around 80 percent of all the stars in the Milky Way. A sobering thought to close the morning as I head upstairs to grind coffee beans and rejuvenate myself with caffeine.

The papers are Gillon, “TRAPPIST-1 and its compact system of temperate rocky planets,” to be published in Handbook of Exoplanets (Springer) and available as a preprint. The Van Looveren paper is “Airy worlds or barren rocks? On the survivability of secondary atmospheres around the TRAPPIST-1 planets,” accepted at Astronomy & Astrophysics (preprint).

White Holes: Tunnels in the Sky?

It’s good now and then to let the imagination soar. Don Wilkins has been poking into the work of Carlo Rovelli at the Perimeter Institute, where the physicist and writer explores unusual ideas, though perhaps none so exotic as white holes. Do they exist, and are there ways to envision a future technology that can exploit them? A frequent contributor to Centauri Dreams, Don is an adjunct instructor of electronics at Washington University, St. Louis, where he continues to track research that may one day prove relevant to interstellar exploration. A white hole offers the prospect of even a human journey to another star, but turning these hypothesized objects into reality remains an exercise in mathematics, although as the essay explains, there are those exploring the possibilities even now.

by Don Wilkins

Among the many concepts for human interstellar travel, one of the more provocative is an offspring of Einstein’s theories, the bright twin of the black hole, the white hole. The existence of black holes (BH), the ultimate compression stage for aging stellar masses above three times the mass of our sun, is announced by theory and confirmed by observation. White holes, the matter spewing counterparts of BHs, escape observation but not the explorations of theorists.

Carlo Rovelli, an Italian theoretical physicist and writer, now the Distinguished Visiting Research Chair at the Perimeter Institute, discusses all this in a remarkably brief book called, simply, White Holes (Riverhead Books, 2023) wherein he travels in company with Dante Alighieri, another author with experience at descents into perilous places. Rovelli makes two remarkable assertions. [1]

1) Rovelli states that another scientist, Daniel Finkelstein, demonstrated that Einstein and other analysts are incorrect when they depict what occurs as one enters a black hole. From the Finkelstein paper (citation below):

The gravitational field of a spherical point particle is then seen not to be invariant under time reversal for any admissible choice of time coordinate. The Schwarzschild surface, r=2m is not a singularity but acts as a perfect unidirectional membrane: causal influences can cross it but only in one direction. [2]

In other words, no time dilation, no spaghettification of trespassers entering a black hole. Schwarzchild’s solution only applies to distant observers; it does not describe the observer crossing the event horizon of the black hole.

2) Rovelli believes in the existence of white holes. His white hole births when the black hole compresses its constituent parts into the realm of quantum mechanics. Rovelli speculates “… a black hole … quantum tunnels into a white one on the inside – and the outside can stay the same.”

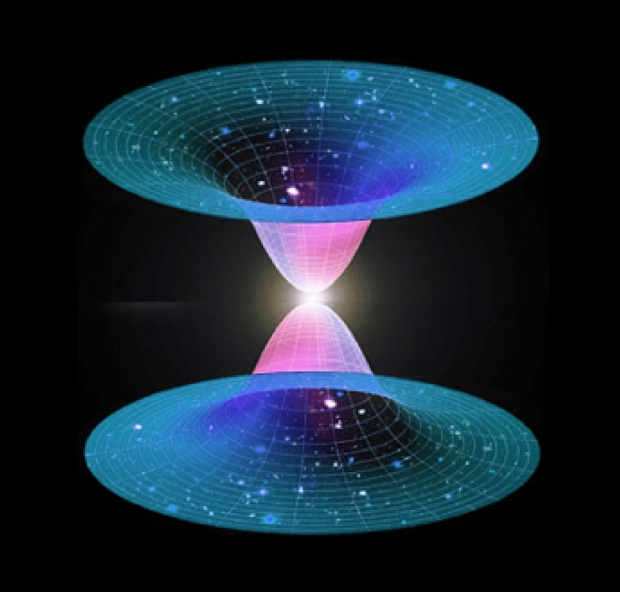

In Figure 1 and Rovelli’s intuition, a quantum mesh separates the black hole and white hole. At these minute dimensions, quantum tunneling effects surge matter away from the black hole, into the mouth of the white hole and back into the Universe.

Figure 1. Relationship between a black hole and a white hole. Credit: C. Rovelli/Aix-Marseille University; adapted by APS/Alan Stonebraker.

The outside of a black hole and a white hole are geometrically identical regardless of the direction of time. The horizon is not reversible under the flow of time. As a result the interiors of the black hole and white hole are identical.

In a paper he co-authored with Hal Haggard, Rovelli writes:

We have constructed the metric of a black hole tunneling into a white hole by using the classical equations outside the quantum region, an order of magnitude estimate for the onset of quantum gravitational phenomena, and some indirect indications on the effects of quantum gravity. [3]

Haggard and Rovelli acknowledge that the calculations do not result from first principles. A full theory of quantum gravity would supply that requirement.

Figure 2: Artist rendering of the black-to-white-hole transition. Credit: F. Vidotto/University of the Basque Country. [9]

Efforts to design a stable wormhole require buttressing the entrance or mouth of the wormhole with prodigious amounts of a hypothesized material, negative matter. Although minute amounts have been claimed to form in the narrow confines of a Casimir device, ideas on how to manufacture planetary-sized masses of negative matter are elusive. [4]

According to recent research, the stability of the WH is dependent upon which of the two major families of matter, bosons or fermions, forms the WH. Bosons are subatomic particles which obey Bose-Einstein statistics and whose spin quantum number has an integer value (0, 1, 2, …). Photons, gluons, the Z neutral weak boson and the weakly charged bosons are bosons. The graviton, if it exists, is a boson. Theoretic analysis of stable traversable WHs founded on bosonic fields demonstrates a need for vast amounts of negative matter to hold open the mouth of a WH.

The other family, the fermions, have odd half-integer (1/2, 3/2, etc.) spins. These particles, electrons, muons, neutrinos, and compound particles, obey the Pauli Exclusion Principle. It is this family that is employed by a team of researchers to describe a two fermion stable white hole [5]. Their configuration produces John Wheeler’s “charge without charge”, where an electric field is trapped within the structure without any physical electrical charge present. The opening in the white hole would be too small, a few hundred Planck lengths (a Planck length is 1.62 x 10-35 meters) to pass gamma rays.

Rovelli reenters the discussion here. [6] The James Webb Space Telescope has identified large numbers of black holes in the early Universe, more black holes than anticipated. Rovelli describes white holes forming from these black holes as Planck-length sized, chargeless entities, unable to interact with the matter except through gravity. In other words, the descendants of the early black holes manifest as the material we describe as dark matter. Rovelli is working on a quantum sensor to detect these white holes.

Once the white holes are detected, it might be possible to capture a white hole. John G. Cramer, professor emeritus of physics at the University of Washington in Seattle, Washington, suggests accelerating the wormhole to almost the speed of light. [7] Aimed at Tau Ceti, he predicts:

The arrival time as viewed through a wormhole is T’ = T/γ , where γ is the Lorentz factor [γ= (1- v/c)-½] and v is the wormhole-end velocity after acceleration. For reference, the maximum energy protons accelerated at CERN LHC have a Lorentz factor of 6,930. Thus, the arrival time at Tau Ceti of an LHC-accelerated wormhole-end would be 15 hours….Effectively, the accelerated wormhole becomes a time machine, connecting the present with an arrival far in the future.

Spraying accelerated electrons through the wormhole could expand the mouth to a size where it could be used as a sensor portal into another star system. The wormhole becomes a multi light-year long periscope, one that scientists could bend and twist to study up close and in detail the star and its companions. Perhaps the wormhole could be expanded enough to pass larger, physical bodies.

Constantin Aniculaesei and an international team of researchers may have overcome the need for an accelerator as large as the LHC to accelerate the white hole to useful size [8]. Developing a novel wakefield accelerator, wherein an intense laser pulse focused onto a plasma excites nonlinear plasma waves to trap electrons, the team’s machine produced 10 Giga electron Volt (GeV) electron bunches. The wakefield accelerator was only ten centimeters long, although a petawatt laser was needed to excite the wakefields.

Cramer hypothesizes that fermionic white holes formed immediately after the Big Bang and in cosmic rays. The gateways to the stars could be found in the cosmic ray bombardment of the Earth or possibly trapped in meteorites. The heavy particles, if ensnared on Earth, would probably sink to the center of the planet.

All that is needed to find a fermionic white hole, Cramer suggests, is a mass spectrometer. But let me quote him on this:

[Wormholes] might be a super-heavy components of cosmic rays….They might be trapped in rocks and minerals….In a mass spectrograph, they could in principle be pulled out of a vaporized sample by an electric potential but would be so heavy that they would move in an essentially undeflected straight line in the magnetic field. …wormholes might still be found in meteorites that formed in a gravity free environment.

The worm hole is essentially unaffected by a magnetic field. A mass detector would point to an invisible mass. The rest, as non-engineers like to say, is merely engineering.

If this line of reasoning is correct – a very large if – enlarged white holes could pass messages and matter through tunnels in the sky to distant stars.

References

1. Carlo Rovelli, translation by Simon Carnell, White Holes, Riverhead Books, USA, 2023

2. David Finkelstein, Past-Future Asymmetry of the Gravitational Field of a Point Particle, Physical Review, 110, 4, pages 965–967, May 1958, 10.1103/PhysRev.110.965

3. Hal M. Haggard and Carlo Rovelli, Black hole fireworks: quantum-gravity effects outside the horizon spark black to white hole tunneling, 4 July 2014, https://arxiv.org/pdf/1407.0989.pdf

4. Matt Visser, Traversable wormholes: Some simple examples, arXiv:0809.0907 [gr-qc], 4 September 2008.

5. Jose Luis Blázquez-Salcedo, Christian Knoll, and Eugen Radu, Traversable Wormholes in Einstein-Dirac-Maxwell theory, arXiv:2010.07317v2, 12 March 2022.

6. What is a white hole? – with Carlo Rovelli, The Royal Institution, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9VSz-hiuW9U

7. John G. Cramer, Fermionic Traversable Wormholes, Analog Science Fiction & Fact, January/February 2022.

8. Constantin Aniculaesei, Thanh Ha, Samuel Yoffe, et al, The Acceleration of a High-Charge Electron Bunch to 10 GeV in a 10-cm Nanoparticle-Assisted Wakefield Accelerator, Matter and Radiation at Extremes, 9, 014001 (2024), https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0161687

9). Rovelli, “Black Hole Evolution Traced Out with Loop Quantum Gravity,” Physics 11, 127 (December 10, 2018).

https://physics.aps.org/articles/v11/127

Alone in the Cosmos?

We live in a world that is increasingly at ease with the concept of intelligent extraterrestrial life. The evidence for this is all around us, but I’ll cite what Louis Friedman says in his new book Alone But Not Lonely: Exploring for Extraterrestrial Life (University of Arizona Press, 2023). When it polled in the United States on the question in 2020, CBS News found that fully two-thirds of the citizenry believe not only that life exists on other planets, but that it is intelligent. That this number is surging is shown by the fact that in polling 10 years ago, the result was below 50 percent.

Friedman travels enough that I’ll take him at his word that this sentiment is shared globally, although the poll was US-only. I’ll also agree that there is a certain optimism that influences this belief. In my experience, people want a universe filled with civilizations. They do not want to contemplate the loneliness of a cosmos where there is no one else to talk to, much less one where valuable lessons about how a society survives cannot be learned because there are no other beings to teach us. Popular culture takes many angles into ETI ranging from alien invasion to benevolent galactic clubs, but on the whole people seem unafraid of learning who aliens actually are.

Image: Louis Friedman, Co-Founder and Executive Director Emeritus, The Planetary Society. Credit: Caltech.

The silence of the universe in terms of intelligent signals is thus disappointing. That’s certainly my sentiment. I wrote my first article on SETI back in the early 1980s for The Review of International Broadcasting, rather confident that by the end of the 20th Century we would have more than one signal to decipher from another civilization. Today, each new report from our active SETI efforts at various wavelengths and in varying modes creates a sense of wonder that a galaxy as vast as ours has yet to reveal a single extraterrestrial.

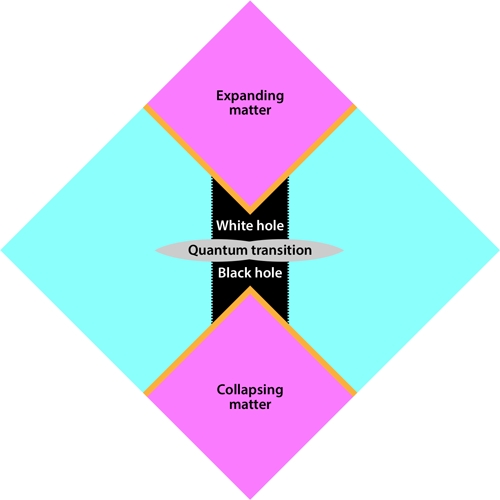

It’s interesting to see how Friedman approaches the Drake equation, which calculates the number of civilizations that should be out there by setting values on factors like star and planet formation and the fraction of life-bearing planets where life emerges. I won’t go through the equation in detail here, as we’ve done that many times on Centauri Dreams. It’s sufficient to note that when Friedman addresses Drake, he cites the estimates for each factor in the current scientific literature and also gives a column with his own guess as to what each of these items might be.

Image: This is Table 1 from Friedman’s book. Credit: Louis Friedman / University of Arizona Press.

This gets intriguing. Friedman comes up with 1.08 civilizations in the Milky Way – that would be us. But he also makes the point that if we just take the first four terms in the Drake equation and multiply them by the time that Earth life has been in existence, we get on the order of two billion planets that should have extraterrestrial life. Thus a point of view I find consistent with my own evolving idea on the matter: Life is all over the place, but intelligent life is vanishingly rare.

Along the way Friedman dismisses the ‘cosmic zoo’ hypothesis that we looked at recently as being perhaps the only realistic way to support the idea that intelligent life proliferates in the Milky Way. Ian Crawford and Dirk Schulze-Makuch see a lot wrong with the zoo hypothesis as well, but argue that the idea we are being observed but not interacted with is stronger than any other explanation for what David Brin and others have called ‘the Great Silence.’ I’ll direct you to Milan M. Ćirković’s The Great Silence: Science and Philosophy of Fermi’s Paradox for a rich explanation both cultural and scientific of our response to the ‘Where are they?’ question.

Before reading Alone But Not Lonely, my own thinking about extraterrestrial intelligence has increasingly focused on deep time. It’s impossible to run through even a cursory study of Earth’s geological history without realizing how tiny a slice our own species inhabits. The awe induced by these numbers tends to put a chill up the spine. The ‘snowball Earth’ episode seems to have lasted, for example, about 85 million years in its entirety. Even if we break it into two periods (accounting for the most severe conditions and excluding periods of lesser ice penetration), we still get two individual eras of global glaciation, each lasting ten million years.

These are matters that are still in vigorous debate among scientists, of course, so I don’t lean too heavily on the precise numbers. The point is simply to cast something as evidently evanescent as our human culture against the inexorable backdrop of geological time. And to contrast even that with a galaxy that is over 13 billion years old, where processes like these presumably occurred in multitudes of stellar systems. What are the odds that, if intelligence is rare, two civilizations would emerge at the same time and live long enough to become aware of each other? And does the lack of hard evidence for extraterrestrial civilizations not make this point emphatic?

But let me quote Friedman on this:

Let’s return to that huge difference between the time scales associated with the start of life on Earth and its evolution to intelligence. The former number was 3.5 to 3.8 billion years ago, a “mere” 0.75 to 1 billion years after Earth formed. Is that just a happenstance, or is that typical of planets everywhere? I noted earlier that intelligence (including the creation of technology) has only been around for 1/2,000,000 of that time—just the last couple thousand years. Life has been on Earth for about 85 percent of its existence; intelligence has been on Earth for about 0.0005 percent of that time. Optimists might want to argue that intelligence is only at its beginning, and after a million years or so those numbers will drastically change, perhaps with intelligence occupying a greater portion of Earth’s history. But that is a lot of optimism, especially in the absence of any other evidence about intelligence in the universe.

Friedman argues that the very fact we can envision numerous ways for humanity to end – nuclear war, runaway climate effects, deadly pandemics – points to how likely such an outcome is. It’s a good point, for technology may well contain within its nature the seeds of its own destruction. What scientists like Frank Tipler and Michael Hart began pointing out decades ago is that it only takes one civilization to overcome such factors and populate the galaxy, but that means we should be seeing some evidence of this. SETI continues the search as it should and we fine-tune our methods of detecting objects like Dyson spheres, but shouldn’t we be seeing something by now?

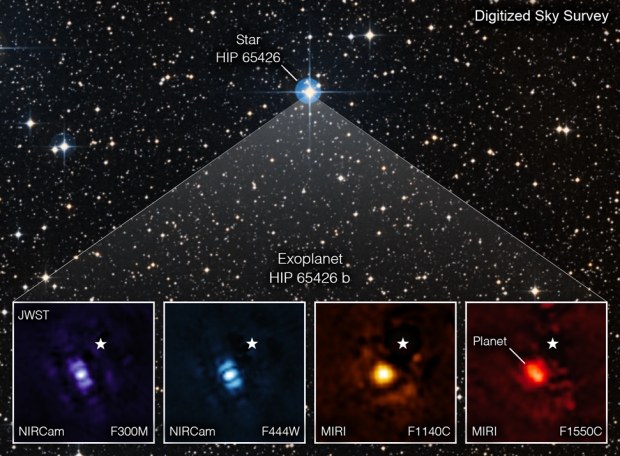

The reason for the ‘but not lonely’ clause in Friedman’s title is that ongoing research is making it clear how vast a canvas we have to analyze for life in all its guises. Thus the image below, which I swipe from the book because it’s a NASA image in the public domain. What I find supremely exciting when looking at an actual image of an exoplanet is that this has been taken by our latest telescope, which is itself in a line of technological evolution leading to completely feasible designs that will one day be able to sample the atmospheres of nearby exoplanets to search for biosignatures.

Image: This image shows the exoplanet HIP 65426 b in different bands of infrared light, as seen from the James Webb Space Telescope: purple shows the NIRCam instrument’s view at 3.00 microns, blue shows the NIRCam instrument’s view at 4.44 microns, yellow shows the MIRI instrument’s view at 11.4 microns, and red shows the MIRI instrument’s view at 15.5 microns. These images look different because of the ways that the different Webb instruments capture light. A set of masks within each instrument, called a coronagraph, blocks out the host star’s light so that the planet can be seen. The small white star in each image marks the location of the host star HIP 65426, which has been subtracted using the coronagraphs and image processing. The bar shapes in the NIRCam images are artifacts of the telescope’s optics, not objects in the scene. Credit: NASA, ESA, CSA, Alyssa Pagan (STScI).

Bear in mind the author’s background. He is of course a co-founder (with Carl Sagan and Bruce Murray) of The Planetary Society. At the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in the 1970s, Friedman was not only involved in missions ranging from Voyager to Magellan, but was part of the audacious design of a solar ‘heliogyro’ that was proposed as a solution for reaching Halley’s Comet. That particular sail proved to be what he now calls ‘a bridge too far,’ in that it was enormous (fifteen kilometers in diameter) and well beyond our capabilities in manufacture, packaging and deployment at the time, but the concept led him to a short book on solar sails and has now taken him all the way into the current JPL effort (led by Slava Turyshev) to place a payload at the solar gravitational lens distance from the Sun. Doing this would allow extraordinary magnifications and data return from exoplanets we may or may not one day visit.

Friedman is of the belief that interstellar flight is simply too daunting to be a path forward for human crews, noting instead the power of unmanned payloads, an idea that fits with his current work with Breakthrough Starshot. I won’t go into all the reasons for his pessimism on this – as the book makes clear, he’s well aware of all the concepts that have been floated to make fast interstellar travel possible, but skeptical they can be adapted for humans. Rather than Star Trek, he thinks in terms of robotic exploration. And even there, the idea of a flyby does not satisfy, even if it demonstrates that some kind of interstellar payload can be delivered. What he’s angling for beyond physical payloads is a virtual (VR) model in which AI techniques like tensor holography can be wrapped around data to construct 3D holograms that can be explored immersively even if remotely. Thus the beauty of the SGL mission:

We can get data using Nature’s telescope, the solar gravity lens, to image exoplanets identified from Earth-based and Earth-orbit telescopes as the most promising to harbor life. It also would use modern information technology to create immersive and participatory methods for scientists to explore the data—with the same definition of exploration I used at the beginning of this book: an opportunity for adventure and discovery. The ability to observe multiple interesting exoplanets for long times, with high-resolution imaging and spectroscopy with one hundred billion times magnification, and then immerse oneself in those observations is “real” exploration. VR with real data should allow us to use all our senses to experience the conditions on exoplanets—maybe not instantly, but a lot more quickly than we could ever get to one.

The idea of loneliness being liberating, which Friedman draws from E. O. Wilson, is a statement that a galaxy in which intelligence is rare is also one which is entirely open to our examination, one which in our uniqueness we have an obligation to explore. He lists factors such as interplanetary smallsats and advanced sail technologies as critical for a mission to the solar gravitational lens, not to mention the deconvolution of images that such a mission would require, though he only hints at what I consider the most innovative of the Turyshev team’s proposals, that of creating ‘self-assembling’ payloads through smallsat rendezvous en-route. In any case, all of these are incremental steps forward, each yielding new scientific discoveries from entirely plausible hardware.

Such virtual exploration does not, of course, rule out SETI itself, including the search for other forms of technosignature than radio or optical emissions. Even if intelligence ultimately tends toward machine incarnation, evidence for its existence might well turn up in the work of a mission to the gravitational lens. So I don’t think a SETI optimist will find much to argue with in this book, because its author makes clear how willing he is to continue to learn from the universe even when it challenges his own conceptions.

Or let’s put that another way. Let’s think as Friedman does of a program of exploration that stretches out for centuries, with not one but numerous missions exploring through ever refined technologies the images that the bending of spacetime near the Sun creates. We keep hunting, in other words, for both life and intelligence, for we know that the cosmos seems to have embedded within it the factor of surprise. A statement sometimes attributed to Asimov comes to mind: “The most exciting phrase to hear in science, the one that heralds new discoveries, is not “Eureka!” (I found it!) but “That’s funny…” The history of astronomy is replete with such moments. There will be more.

The book is Friedman, Alone but Not Lonely: Exploring for Extraterrestrial Life, University of Arizona Press, 2023.

Open Cluster SETI

Globular clusters, those vast ‘cities of stars’ that orbit our galaxy, get a certain amount of traction in SETI circles because of their age, dating back as they do to the earliest days of the Milky Way. But as Henry Cordova explains below, they’re a less promising target in many ways than the younger, looser open clusters which are often home to star formation. Because it turns out that there are a number of open clusters that likewise show considerable age. A Centauri Dreams regular, Henry is a retired map maker and geographer now living in southeastern Florida and an active amateur astronomer. Here he surveys the landscape and points to reasons why older open clusters are possible homes to life and technologies. Yet they’ve received relatively short shrift in the literature exploring SETI possibilities. Is it time for a new look at open clusters?

by Henry Cordova

If you’re looking for signs of extra-terrestrial intelligence in the cosmos, whether it be radio signals or optical beacons or technological residues, doesn’t it make sense to observe an area of sky where large numbers of potential candidates (particularly stars) are concentrated? Galaxies, of course, are large concentrations of stars, but they are so remote that it is doubtful we would be able to detect any artifacts at those distances. Star clusters are concentrations of stars gathered together in a small area of the celestial sphere easily within the field of view of a telescope or radio antenna. These objects also have the advantage that all their members are at the same distance, and of the same age,

Ask any amateur astronomer; “How many kinds of star cluster are there?” and he will answer; “Two, Open Clusters (OCs) and Globular Clusters (GCs)”. The terms “Globular” and “Open” refer to both their general morphology as well as their appearance through the eyepiece. It’s important to keep in mind that both are collections of stars presumably born at the same time and place (and hence, from the same material) but they are nevertheless very different kinds of objects. There does not seem to be a clearly defined transitional or intermediate state between the two. One type does not evolve into the other. Incidentally, the term ‘Galactic Cluster’ is often encountered when researching this field. It is an obsolete term for an OC and should be abandoned. It is too easily misunderstood as meaning a ‘cluster of galaxies’ and can lead to confusion.

GCs are in fact globular. They are collections of thousands, if not hundreds of thousands, of stars forming spheroidal aggregates much more densely packed towards their centers. OCs are amorphous and irregular in shape, random clumps of several hundred to several thousand stars resembling clouds of buckshot flying through space. Their distribution throughout the galaxy is different as well. GCs orbit the galactic center in highly elliptical orbits scattered randomly through space. They are, for the most part, located at great distances from us. OCs, on the other hand, appear to be restricted to mostly circular orbits in the plane of the Milky Way. Due to the obscuring effects of interstellar dust in the plane of the galaxy, most are seen relatively near Earth. although they are scattered liberally throughout the spiral arms.

Image: The NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope has captured the best ever image of the globular cluster Messier 15, a gathering of very old stars that orbits the center of the Milky Way. This glittering cluster contains over 100 000 stars, and could also hide a rare type of black hole at its center. The cluster is located some 35 000 light-years away in the constellation of Pegasus (The Winged Horse). It is one of the oldest globular clusters known, with an age of around 12 billion years. Very hot blue stars and cooler golden stars are seen swarming together in this image, becoming more concentrated towards the cluster’s bright center. Messier 15 is also one of the densest globular clusters known, with most of its mass concentrated at its core. Credit: NASA, ESA.

Studies of both types of clusters in nearby galaxies confirm these patterns are general, not a consequence of our Milky Way’s history and architecture, but a feature of galactic structure everywhere. Other galaxies are surrounded by clouds of GCs, and swarms of OCs circle the disks of nearby spirals. It appears that the Milky Way hosts several hundred GCs and several thousand OCs. It is now clear that not only is the distribution and morphology of star clusters divided into two distinct classes but their populations are as well. OCs are often associated with clouds of gas and dust, and are sometimes active regions of star formation. Their stellar populations are often dominated by massive bright, hot stars evolving rapidly to an early death. GCs, on the other hand, are relatively dust and gas free, and the stars there are mostly fainter and cooler, but long-lived. Any massive stars in GCs evolved into supernovae, planetary nebulae or white dwarfs long ago.

It appears that the globulars are very old. They were created during the earliest stages of the galaxy’s evolution. Conditions must have been very different back then; indeed, globulars may be almost as old as the universe itself. GC stars formed during a time when the interstellar medium was predominantly hydrogen and helium and their spectra now reveal large concentrations of heavy elements (“metals”, in astrophysical jargon). The metals have been carried up from the stellar cores by convective processes late in the stars’ life. Any planets formed around this early generation of stars would likely be gas giants, composed primarily of H and He—not the rocky Earth-type worlds we tend to associate with life.

Open Clusters, on the other hand, are relatively new objects. Many of them we can see are still in the process of formation, condensing from molecular clouds well enriched by metals from previous cycles of nucleogenesis and star formation. These clouds have been seeded by supernovae, solar winds and planetary nebulae with fusion products so that subsequent generations of stars will have the higher elements to incorporate in their own retinue of planets.

Image; Some of our galaxy’s most massive, luminous stars burn 8,000 light-years away in the open cluster Trumpler 14. Credit: NASA, ESA, and J. Maíz Apellániz (Institute of Astrophysics of Andalusia, Spain); Acknowledgment: N. Smith (University of Arizona).

Older OCs may have broken up due to galactic tidal stresses but new ones seem to be forming all the time, and there appears to be sufficient material in the galactic plane to ensure a continuous supply of new OCs for the foreseeable future. In general, GCs are extremely old and stable, but not chemically enriched enough to be suitable for life. OCs are young, several million years old, and they usually don’t survive long for life to evolve there. Any intelligent life would probably evolve after the cluster broke up and its stars dispersed. BUT…there are exceptions.

The most important parameter that determines a star’s history is its initial mass. All stars start off as gravitationally collapsing masses of gas, glowing from the release of gravitational potential energy. Eventually, temperatures and pressures in the stars’ cores rise to the point where nuclear fusion reactions start producing light and heat. This energy counteracts gravity and the star settles down to a long period of stability, the main sequence. The terminology arises from a line of stars in the color-magnitude diagram of a star cluster. Main sequence stars stay on this line until they run out of fuel and wander off the main sequence.

All stars follow the same evolutionary pattern, but where on the main sequence they wind up, and how long they stay there, depend on their initial mass. Massive stars evolve quickly, lighter ones tend to stay on the main sequence a long time. Our Sun has been a main sequence star for about 4.6 billion years, and it will remain on the main sequence for about another 5 billion years. When it runs out of nuclear fuel it will wander off the main sequence, getting brighter and cooler as it evolves.

All stars evolve in a similar way, but the amount of time they spend in that stable main sequence state is highly dependent on their mass at birth. Studying the point on the color-magnitude diagram of a cluster’s main sequence where stars start to “peel-off” from the MS allows astrophysicists to determine the age of the cluster. It is not necessary to know the absolute brightness, or distance, of the stars since, by definition, all the stars in a cluster are at the same distance. The color-magnitude (or Hertzprung-Russell) diagram is as important to astronomy as the periodic table is to chemistry. It allows us to visualize stellar evolution using a simple graphic model to interpret the data. It is one of the triumphs of 20th century science.

It is this ability to determine the age of a cluster that allows us to select a set of OCs that meet the criterion of great age needed for biological evolution to take place. Although open clusters tend to quickly lose their stars through gravitational interactions with molecular clouds in the disc of the galaxy, a surprising number seem to have survived long enough for biological, and possibly technologically advanced, species to evolve. Although less massive stars, such as main sequence red dwarfs, tend to be preferentially ejected from OCs due to gravitational tides, more massive F, G, and K stars are more likely to remain.

Sky Catalog 2000.0 (1) lists 32 OCs of ages greater than 1.0 Gyr. A more up-to-date reference, the Wikipedia entry (2), lists others. No doubt, a thorough search of the literature will reveal still more. A few of these OCs are comparable in age to the globulars. They are relics of an ancient time. But many others are comparable to our Sun in age (indeed, our own star, like many others, was born in an open cluster).

Regardless of the observing technique or wavelength utilized, an OC provides the opportunity to examine a large number of stars simultaneously, stars which have been pre-selected as being of a suitable age to support life or a technically advanced civilization. It will also be assured that, as members of an OC, all the stars sampled were formed in a metal-rich environment, and that any planets formed about those stars may be rocky or otherwise Earthlike.

If a technical civilization has arisen on any of those stars, it is possible that they have explored or colonized other stars in the cluster and we have the opportunity to eavesdrop on intra-cluster communications. And from the purely practical point of view, when acquiring scarce funding or telescope time for such a project, it will be possible to piggy-back a SETI program onto non-SETI cluster research. Other than SETI, there are very good reasons to study OCs. They provide a useful laboratory for investigations into stellar evolution.

References

1) Sky Catalog 2000.0, Vol II, Sky Publishing Corp, 1985.

2) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_open_clusters

Suggestions for Additional reading

1. H. Cordova, The SETI Potential of Open Star Clusters, SETIQuest, Vol I No 4, 1995

2. R. De La Fuente Marcos, C. De La Fuente Marcos, SETI in Star Clusters: A Theoretical Approach, Astrophysics and Space Science 284: 1087-1096, 2003

3. M.C. Turnbull, J.C. Tarter, Target Selection for SETI II: Tycho-2 Dwarfs, Old Open Clusters, And the Nearest 100 Stars, ApJ Supp. Series 149: 423-436, 2003