Centauri Dreams

Imagining and Planning Interstellar Exploration

Braking at Centauri: A Bound Orbit at Proxima?

One of the great problems of lightsail concepts for interstellar flight is the need to decelerate. Here I’m using lightsail as opposed to ‘solar sail’ in the emerging consensus that a solar sail is one that reflects light from our star, and is thus usable within the Solar System out to about 5 AU, where we deal with the diminishment of photon pressure with distance. Or we could use the Sun with a close solar pass to sling a solar sail outbound on an interstellar trajectory, acknowledging that once our trajectory has been altered and cruise velocity obtained, we might as well stow the now useless sail. Perhaps we could use it for shielding in the interstellar medium or some such.

A lightsail in today’s parlance defines a sail that is assumed to work with a beamed power source, as with the laser array envisioned by Breakthrough Starshot. With such an array, whether on Earth or in space, we can forgo the perihelion pass and simply bring our beam to bear on the sail, reaching much higher velocities. Of the various materials suggested for sails in recent times, graphene and aerographite have emerged as prime candidates, both under discussion at the recent Montreal symposium of the Interstellar Research Group. And that problem of deceleration remains.

Is a flyby sufficient when the target is not a nearby planet but a distant star? We accepted flybys of the gas giants as part of the Voyager package because we had never seen these worlds close up, and were rewarded with images and data that were huge steps forward in our understanding of the local planetary environment. But an interstellar flyby is challenging because at the speeds we need to reach to make the crossing in a reasonable amount of time, we would blow through our destination system in a matter of hours, and past any planet of interest in perhaps a matter of minutes.

Robert Forward’s ingenious ‘staged’ lightsail got around the problem by using an Earth-based laser to illuminate one part of the now separated sail ring, beaming that energy back to the trailing part of the sail affixed to the payload and allowing it to decelerate. Similar contortions could divide the sail again to make it possible to establish a return trajectory to Earth once exploration of the distant stellar system was complete. We can also consider using magsail concepts to decelerate, or perhaps the incident light from a bright target star could allow sufficient energy to brake against.

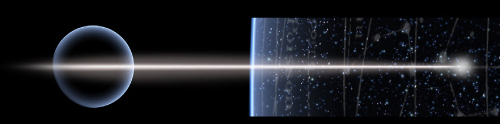

Image: Forward’s lightsail separating at the beginning of its deceleration phase. Laser sailing may turn out to be the best way to the stars, provided we can work out the enormous technical challenges of managing the outbound beam. Or will we master fusion first? Credit: R.L. Forward.

But time is ever a factor, because you want to reach your target quickly, while at the same time, if you approach it too fast, you’re incapable of creating the needed deceleration. Moreover, what is your target? A bright star gives you options for deceleration if you approach at high velocity that are lacking from, say, a red dwarf star like Proxima Centauri, where the closest terrestrial-class world we know is in what appears to be a habitable zone orbit. In Montreal, René Heller (Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research), a familiar name in these pages, laid out the equations for a concept he has been developing for several years, a mission that could use not only the light of Proxima itself but from Centauri A and B to create a deceleration opportunity. You can follow Heller’s presentation at Montreal here.

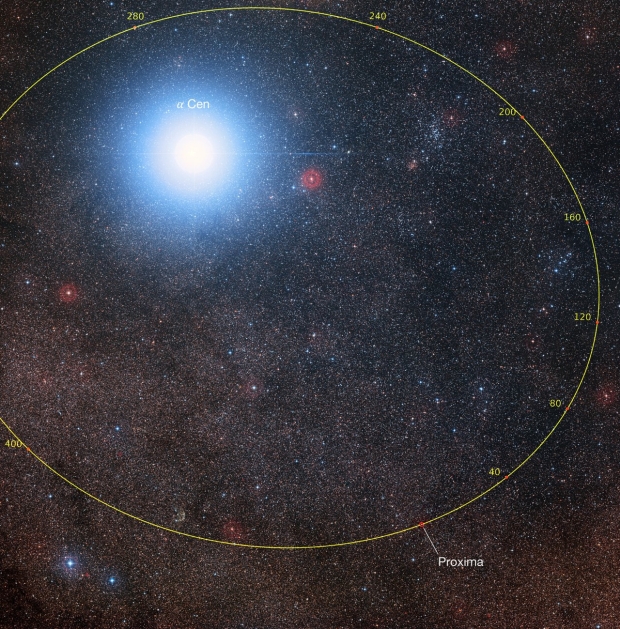

Remember what we’re dealing with here. We have two stars in the central binary, Centauri A (G-class) and Centauri B (K-class), with the M-class dwarf Proxima Centauri about 13000 AU distant. Centauri A and B are close – their distance as they orbit around a common barycenter varies from 35.6 AU to 11.2 AU. These are distances in Solar System range, meaning that 35.6 AU is roughly the orbit of Neptune, while 11.2 AU is close to Saturn distance. Interesting visual effects in the skies of any planet there.

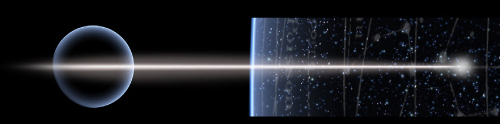

Image: Orbital plot of Proxima Centauri showing its position with respect to Alpha Centauri over the coming millennia (graduations are in thousands of years). The large number of background stars is due to the fact that Proxima Cen is located very close to the plane of the Milky Way. Proxima’s orbital relation to the central stars becomes profoundly important in the calculations Heller and team make here. Credit: P. Kervella (CNRS/U. of Chile/Observatoire de Paris/LESIA), ESO/Digitized Sky Survey 2, D. De Martin/M. Zamani.

Using a target star for deceleration by braking against incident photons has been studied extensively, especially in recent years by the Breakthrough Starship team, where the question of how its tiny sailcraft could slow from 20 percent of the speed of light to allow longer time at target is obviously significant. Deceleration into a bound orbit at Proxima would be, of course, ideal but it turns out to be impossible given the faint photon pressure Proxima can produce. Investing decades of research and 20 years of travel time is hardly efficient if time in the system is measured in minutes.

In fact, to use photon pressure from Proxima Centauri, whose luminosity is 0.0017 that of the Sun, would require approaching the star so slowly to decelerate into a bound orbit that the journey would take thousands of years. Hence Heller’s notion of using the combined photon pressure and gravitational influences of Centauri A and B to work deceleration through a carefully chosen trajectory. In other words, approach A, begin deceleration, move to B and repeat, then emerge on course outbound to Proxima, where you’re now slow enough to use its own photons to enter the system and stay.

Working with Michael Hippke (Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research, Göttingen) and Pierre Kervella (CNRS/Universidad de Chile), Heller has refined the maximum speed that can be achieved on the approach into Alpha Centauri A to make all this happen: 16900 kilometers per second. If we launch in 2035, we arrive at Centauri A in 2092, with arrival at Centauri B roughly six days later and, finally, arrival at Proxima Centauri for operations there in a further 46 years. That launch time is not arbitrary. Heller chose 2035 because he needs Centauri A and B to be in precise alignment to allow the gravitational and photon braking effects to work their magic.

So we have backed away from Starshot’s goal of 20 percent of lightspeed to a more sedate 5.6 percent, but with the advantage (if we are patient enough) of putting our payload into the Proxima Centauri system for operations there rather than simply flying through it at high velocity. We also get a glimpse of the systems at both Centauri A and B. I wrote about the original Heller and Hippke paper on this back in 2017 and followed that up with Proxima Mission: Fine-Tuning the Photogravitational Assist. I return to the concept now because Heller’s presentation contrasts nicely with the Helicity fusion work we looked at in the previous post. There, the need for fusion to fly large payloads and decelerate into a target was a key driver for work on an in-space fusion engine.

Interstellar studies works, though, through multiple channels, as it must. Pursuing fusion in a flight-capable package is obviously a worthy goal, but so is exploring the beamed energy option in all its manifestations. I note that Helicity cites a travel time to Proxima Centauri in the range of 117 years, which compares with Heller and company’s now fine-tuned transit into a bound orbit at Proxima of 121 years. The difference, of course, is that Helicity can envision launching a substantially larger payload.

Clearly the pressure is on fusion to deliver, if we can make that happen. But the fact that we have gone from interstellar flight times thought to involve thousands of years to a figure of just over a century in the past few decades of research is heartening. No one said this would be easy, but I think Robert Forward would revel in the thought that we’re driving the numbers down for a variety of intriguing propulsion options.

The paper René Heller drew from in the Montreal presentation is Heller, Hippke & Kervella, “Optimized Trajectories to the Nearest Stars Using Lightweight High-velocity Photon Sails,” Astronomical Journal Vol. 154 No. 3 (29 August 2017), 115. Full text.

Interstellar Path? Helicity’s Bid for In-Space Fusion

Be aware that the Interstellar Research Group has made the videos shot at its Montreal symposium available. I find this a marvelous resource, and hope I never get jaded with the availability of such materials. I can remember hunting desperately for background on talks being given at astronomical conferences I could not attend, and this was just 20 years ago. Now the growing abundance of video makes it possible for those of us who couldn’t be in Montreal to virtually attend the sessions. Nice work by the IRG video team!

There is plentiful material here for the interstellar minded, and I will be drawing on this resource in days ahead. But let’s start with fusion, because it’s a word that all too easily evokes a particular reaction in those of us who have been writing about the field for some time. Fusion has always seemed to be the flower about to bloom, even as decades of research have passed and the target of practical power generation hovers in the future. In terms of propulsion, I’ve long felt that if we had so much trouble igniting fusion on Earth, how much longer would it be before we could translate our knowledge into the tight dimensions of a drive for an interstellar spacecraft?

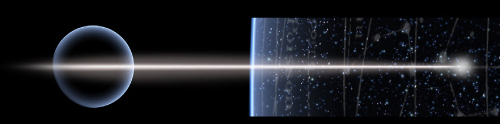

But if you’ll take a look at Helicity Space’s presentation at the Montreal symposium, you’ll learn about a tightly focused company that approaches fusion from a different direction. Rather than starting with fusion reactors designed to produce power on Earth, Helicity’s entire focus is building a fusion drive for space. NASA’s Alan Stern, of New Horizons fame but also a veteran of decades of space exploration, is senior technical advisor here, and as he puts it, “our goal is not to power up New York City but to push spacecraft.” Stern appeared at Montreal to introduce a panel including Stephane Lintner, the company’s CEO and chief scientist Setthivoine You.

Let’s assume for a moment that at some point in the coming years – we can hope sooner rather than later – we do develop in-space propulsion using fusion. The easiest approach is to contrast working fusion with the methods available to us today. New Horizons was, shortly after launch, the fastest spacecraft ever built; it crossed the orbit of the Moon in a scant 9 hours, but it took a decade to reach Pluto/Charon. We can use gravity assists to sling a payload to the Kuiper Belt, perhaps a craft like JHU/APL’s Interstellar Probe concept, but here we’re dependent on planetary geometry, which isn’t always cooperative, and doesn’t provide the kind of boost that fusion could.

Image: Setthivoine You, co-founder and chief scientist at Helicity Space.

I’m a great advocate of sails, both solar sails and so-called ‘lightsails’ driven by beamed energy, but if reaching a distant target fast is the goal, we’re constrained by the need for a large laser installation and the likelihood, in the near future anyway, of pushing sails that are tiny. New Horizons would take two centuries to reach the Sun’s gravitational lens, a target of JPL’s SGL mission, which will use tight perihelion passes of multiple craft to get up to speed. We continue to talk about decades of travel time, even within the Solar System. As for interstellar, Breakthrough Starshot’s tiny craft, perhaps sent as a swarm to Proxima Centauri, might reach the target in 20 years if all goes well, but data return is a huge problem, and the mission can only be a flyby.

Helicity boldly sketches a future in which we might combine Interstellar Probe and the SGL mission into a single operation using a craft capable of taking a 5 ton payload to the gravitational lens (roughly 600 AU) in a little over a decade. Pluto becomes reachable in some of the Helicity concepts in about a year, with a craft carrying far heavier payloads than New Horizons and abundant power for operations and communications. All this in craft that could be carried into space by existing vehicles like Falcon Heavy or the SLS. The vision reminds us of The Expanse – imagine 4 months to Mars carrying 450 tons of payload as one step along the way.

All of this is a science fictional vision, but the work coming out of Helicity’s labs is solid. It involves so-called peristaltic magnetic compression to compress plasma and raise energy density. The method relies on specific stable behaviors within the plasma, a type of ‘Taylor State’ – these describe plasma within strong magnetic fields – discovered by You. These confine the plasma, while magnetic reconnection heating preheats it in the first place. Setthivoine You describes all this in the video, noting that what Helicity is developing is a method that we can consider magneto-inertial confinement, one producing a plasma jet stabilized through shear flows within the plasma itself. The firm’s computer simulations, in collaboration with Los Alamos National Laboratories, show four jets merging in a double-helix fashion inside the magnetic nozzle. You’s slides, available in the video, are instructive and dramatic.

What emerges from these results is scalable performance, allowing a path forward that the firm hopes to test as early as 2026 in a demonstration flight in orbit, with the possibility of a functional spacecraft at TRL 9 within roughly a decade. The scalable design points to the possibility of compact, reusable spacecraft with the unique feature of continuous thrusting. Think of the Helicity system, Stern has suggested, as a kind of afterburner put onto an electric propulsion system, and one that can scale into a working fusion drive. The concept scales by adding more fusion jets, allowing higher and higher efficiency, until the engine eventually becomes self-sustaining – the energy required to sustain the thrust is less than what the fusion begins to generate.

Does Helicity’s technology have the inside track, or will a contender like the UK’s Pulsar Fusion get to in-space fusion first? The latter is working on a study with Princeton Satellite Systems to examine plasma characteristics in a fusion rocket engine. Helicity’s founders are appropriately cautious about their work and stress how much needs to be learned, but they are continuing to develop the concept in their prototypes. With its laboratory in Pasadena, the company is privately funded and maintains active collaborations with Caltech and Los Alamos as well as UMBC and Swarthmore. Grants from the Department of Energy and other sources have likewise contributed. Have a look at the Montreal video to get a sense of where this exciting research stands, and also a glimpse of the kind of future that in-space fusion propulsion could produce.

Save New Horizons

The idea that we might take an active, working spacecraft in the Kuiper Belt and not only repurpose it for a different task (heliophysics) but also dismiss the team that is now running it is patently absurd. Yet this appears to be a possibility when it comes to New Horizons, the remarkable explorer of Pluto/Charon, Arrokoth, and the myriad objects of the Kuiper Belt. NASA’s Science Mission Directorate, responding to a 2022 Senior Review panel which had praised New Horizons, is behind the controversy, about which you can read more in NASA’s New Horizons Mission Still Threatened.

So absurd is the notion that I’m going to assume this radical step, apparently aimed at ending the Kuiper Belt mission New Horizons was designed for on September 30 of 2024, will not happen, heartened by a recent letter of protest from some figures central to the space community, as listed in the above article from Universe Today. These are, among a total of 25 planetary scientists, past Planetary Society board chair Jim Bell, Lori Garver (past Deputy Administrator of NASA), Jim Green (Past Director of NASA’s Planetary Science Division), Candice Hansen-Koharcheck (Past chair of the American Astronomical Society’s Division of Planetary Sciences and Past Chair of NASA’s Outer Planets Assessment Group), author Homer Hickham, Wesley T. Huntress (Past Director of NASA’s solar system Exploration Group), astrophysicist Sir Brian May, and Melissa McGrath (past NASA official and AAS Chair of DPS).

Needless to say, we’ll keep a wary eye on the matter (and I’ve just signed the petition to save the original mission), but let’s talk this morning about what New Horizons is doing right now, as the science remains deeply productive. I like the way science team member Tod Lauer spoke of the spacecraft’s current position in a recent post on the team’s website, a place where “It’s still convenient to think of neat north and south hemispheres to organize our vista of the sky, but the equator is now defined by the band of the galaxy, not our spinning Earth, lost to us in the glare of the fading Sun.”

Places like that evoke the poet in all of us. Lauer points out that the New Horizons main telescope is no more powerful than what amateur stargazers willing to open their checkbooks might use in their backyards. Part of the beauty of the situation, though, is that New Horizons moves in a very dark place indeed. While I have vivid memories of seeing a glorious Milky Way bisecting the sky aboard a small boat one summer night on Lake George in the Adirondacks, how much more striking is the vantage out here in the Kuiper Belt where the nearest city lights are billions of kilometers away?

Image: A Kuiper Belt explorer looks into the galaxy. Credit: Serge Brunier/Marc Postman/Dan Durda

The science remains robust out here as well. Consider what Lauer notes in his article. Looking for Kuiper Belt objects using older images, the New Horizons team found that in all cases, even objects far from the Milky Way’s band appeared against a background brighter than scientists can explain, even factoring in the billions of galaxies that fill the visible cosmos. The puzzle isn’t readily solved. Says Lauer:

…we then tried observations of a test field carefully selected to be far away from the Milky Way, any bright stars, clouds of dust – or anything, anything that we could think of that would wash out the fragile darkness of the universe. The total background was much lower than that in our repurposed images of Kuiper Belt objects – but by exactly the amount we expected, given our care at pointing the spacecraft at just about the darkest part of the sky we could find. The mysterious glow is still there, and more undeniable, given the care we took to exclude anything that would compete with the darkness of the universe, itself. You’re in an empty house, far out in the country, on a clear moonless night. You turn off all the lights everywhere, but it’s still not completely dark. The billions of galaxies beyond our Milky Way are still there, but what we measure is twice as bright as all the light they’ve put out over all time since the Big Bang. There is something unknown shining light into our camera. If it’s the universe, then it’s just as strong, just as bright, as all the galaxies that ever were.

Only New Horizons can do this kind of work. How far are we from Earth? Take a look at the animated image below, which is about as vivid a reminder as I can find.

Image: Two images of Proxima Centauri, one taken by NASA’s New Horizons probe and the other by ground-based telescopes. The images show how the spacecraft’s view, from a distance of 7 billion kilometers, is very different from what we see on Earth, illustrating the parallax effect. Credit: NASA/Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory/Southwest Research Institute/Las Cumbres Observatory/Siding Spring Observatory.

With 15 more dark fields slated for examination this summer, New Horizons remains active on this and many other fronts. In his latest PI’s Perspective, Alan Stern notes the eight-week period of observations taking place now and through September. include continued observations of KBOs, imaging of the ice giants, dust impact measurements, mapping of hydrogen gas in the outer heliosphere, analysis using the ultraviolet spectrometer to look for structures in the interstellar medium, and spatial variations in the visible wavelength background. Six months of data return will be needed to download the full set for the planetary, heliospheric and astrophysics communities.

According to Stern, new fault protection software will allow New Horizons to operate out to 100 AU. That assumes we’ll still be taking Kuiper Belt data. Given the utterly unique nature of this kind of dataset and the fact that this spacecraft is engaged in doing exactly what it was designed to do, it is beyond comprehension that its current mission might be threatened with a shakeup to the core team or a reframing of its investigations. I’ve come across the National Space Society’s petition to save the New Horizons Kuiper Belt mission late, but please take this chance to sign it.

Rethinking Planet 9

Trans-Neptunian Objects, or TNOs, sound simple enough, the term being descriptive of objects moving beyond the orbit of Neptune, which means objects with a semimajor axis greater than 30 AU. It makes sense that such objects would be out there as remnants of planet formation, but they’re highly useful today in telling us about what the outer system consists of. Part of the reason for that is that TNOs come in a variety of types, and the motions of these objects can point to things we have yet to discover.

Thus the cottage industry in finding a ninth planet in the Solar System, with all the intrigue that provides. The current ‘Planet 9 Model’ points to a super-Earth five to ten times as massive as our planet located beyond 400 AU. It’s a topic we’ve discussed often in these pages. I can recall the feeling I had long ago when I first learned that little Pluto really didn’t explain everything we were discovering about the system beyond Neptune. It simply wasn’t big enough. That pointed to something else, but what? New planets are exciting stuff, especially when they are nearby, as the possibility of flybys and landings in a foreseeable future is real.

Image: An artist’s illustration of a possible ninth planet in our solar system, hovering at the edge of our solar system. Neptune’s orbit is show as a bright ring around the Sun. Credit: ESO/Tom Ruen/nagualdesign.

But a different solution for a trans-Neptunian planet is possible, as found in the paper under discussion today. Among the active researchers into the more than 1000 known TNOs and their movements are Patryk Sofia Lykawka (Kobe University) and Takashi Ito (National Astronomical Observatory of Japan), who lay out the basics about these objects in a new paper that has just appeared in The Astronomical Journal. The astronomers point out that we can use them to learn about the formation and evolution of the giant planets, including possible migrations and the makeup of the protoplanetary disk that spawned them. But it’s noteworthy that no single evolutionary model exists that would explain all known TNO orbits in a unified way.

So the paper goes to work on such a model, and while concentrating on the Kuiper Belt and objects with semimajor axes between 50 and 1500 AU, the authors pin down four populations, and thus four constraints that any successful model of the population must explain. The first of these are detached TNOs, meaning objects that are outside the gravitational influence of Neptune and thus not locked into any mean motion resonance with it. The second is a population the authors consider statistically significant, TNOs with orbital inclinations to the ecliptic above 45 degrees. This population is not predicted by existing models of early Neptune migration.

The paper is generous with details about these and the following two populations, but here I’ll just give the basics. The third group consists of TNOs considered to be on extreme orbits. Here we fall back on the useful Sedna and other objects with large values for perihelion of 60 AU or more. These demand that we find a cause for perturbations beyond the four giant planets, possibly even a rogue planet’s passing. Any model of the outer system must be able to explain the orbits of these extreme objects, an open question because interactions with a migrating Neptune do not suffice.

Finally, we have a population of TNOs that are stable in various mean motion resonances with Neptune over billions of years – the authors call these “stable resonance TNOs” – and it’s interesting to note that most of them are locked in a resonance of approximately 4 billion years, which points to their early origin. The point is that we have to be able to explain all four of these populations as we evolve a theory on what kind of objects could produce the observable result.

What a wild place the outer Solar System would have been during the period of planet formation. The authors believe it likely that several thousand dwarf planets with mass in the range of Pluto and “several tens” of sub-Earth and Earth-class planets would have formed in this era, most of them lost through gravitational scattering or collisions. We’ve been looking at trans-Neptunian planet explanations for today’s Kuiper Belt intensely for several decades, but of the various suggested possibilities, none explained the orbital structure of the Kuiper Belt to the satisfaction of Lykawka and Ito. The existing Planet 9 model here gives way to a somewhat closer, somewhat smaller world deduced from computer simulations examining the dynamical evolution of TNOs.

What the authors introduce, then, is the possibility of a super-Earth perhaps as little as 1.5 times Earth’s mass with a semimajor axis in the range of 250 to 500 AU. The closest perihelion works out to 195 au in these calculations, with an orbit that is inclined 30 degrees to the ecliptic. If we plug such a world into this paper’s simulations, we find that it explains TNOs that are decoupled from Neptune and also many of the high-inclination TNOs, while being compatible with resonant orbit TNOs stable for billions of years. The model thus broadly fits observed TNO populations.

But there is a useful addition. In the passage below, the italics are mine:

…the results of the KBP scenario support the existence of a yet-undiscovered planet in the far outer solar system. Furthermore, this scenario also predicts the existence of new TNO populations located beyond 150 au generated by the KBP’s perturbations that can serve as observationally testable signatures of the existence of this planet. More detailed knowledge of the orbital structure in the distant Kuiper Belt can reveal or rule out the existence of any hypothetical planet in the outer solar system. The existence of a KBP may also offer new constraints on planet formation and dynamical evolution in the trans-Jovian region.

A testable signature is the gold standard for a credible hypothesis, which is not to say that we will necessarily find it. But if we do locate such a world, or a planet corresponding to the more conventional Planet 9 scenarios, we will have ramped up our incentive to explore beyond the Kuiper Belt, an incentive already given further impetus by our growing knowledge of the heliosphere and its interactions with the interstellar medium. But to the general public, interstellar dust is theoretical. An actual planet – a place that can be photographed and one day landed upon – awakens curiosity and the innate human drive to explore with a target that pushes all our current limits.

The paper is Lykawka & Ito, “Is There an Earth-like Planet in the Distant Kuiper Belt?,” Astronomical Journal Vol. 166, No. 3 (25 August 2023) 118 (full text).

Interstellar Probe: Into the G Cloud

We’re living in a prime era for studying the Solar System’s movement through the galaxy, with all that implies about stellar evolution, planet formation and the heliosphere’s interactions with the interstellar medium. We don’t often think about movements at this macro-scale, but bear in mind that the Sun and the planets are now moving through the outer edges of what is known as the local interstellar cloud (LIC), having been within the cloud by some estimates for about 60,000 years.

What happens next? I always think about Poul Anderson’s wonderful Brain Wave when contemplating such matters. In the classic 1954 tale, serialized the year before in Space Science Fiction during the great 1950s boom in science fiction magazines, Brain Wave depicts the Earth’s movement out of an energy-damping field it had moved through since the Cretaceous. When the planet moves out of this field at long last, everyone on the planet gets smarter. What will happen when we leave the LIC?

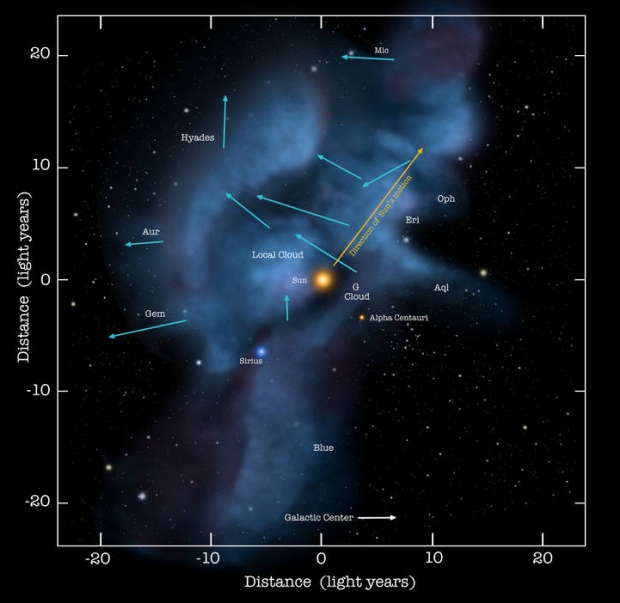

Nothing this dramatic, as far as anyone can tell, but we’re moving into the so-called G-cloud, a somewhat denser region we’ll get to know within a few thousand years (Alpha Centauri is already within the G-cloud). The LIC appears to be about 30 light years across, sporting somewhat higher density hydrogen than the interstellar medium around it and flowing from the direction of Scorpius and Centaurus. We seem to be moving through its outer edge.

Image: That’s a Richard Powers cover on the first edition of Poul Anderson’s Brain Wave, illustrating a novel Anderson considered one of his best.

The word ‘denser’ has to be kept in perspective. Consider that about half of the interstellar gas – hydrogen and helium for the most part – takes up 98 percent of the space between the stars and is thus extraordinarily low in density, The other half of this gas is compressed into 2% of the volume and is found in molecular clouds, mostly molecular hydrogen, that include some carbon monoxide and higher concentrations of dust than the surrounding ISM.

We’d like to know more about the G-cloud, and in particular such factors as its temperatures and density, for just how the heliosphere reacts to this changing environment, presumably through compression, could have effects upon its shape and thus its shielding effects from cosmic rays. Thus the importance of the Interstellar Probe mission (ISP) out of Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory that we’ve discussed often in these pages (I’ll point you to Mapping Out Interstellar Clouds for more on the subject). One thing I noted in an article last year was that there are alternative models to the Sun’s nearby cloud environment, some challenging the idea that the LIC and the G-cloud are distinct regions. Interstellar Probe would help in the investigation.

Image: Our solar journey through space is carrying us through a cluster of very-low-density interstellar clouds. Right now the Sun is inside of a cloud (Local cloud) that is so tenuous that the interstellar gas detected by the IBEX (Interstellar Boundary Explorer mission) is as sparse as a handful of air stretched over a column that is hundreds of light-years long. These clouds are identified by their motions, indicated in this graphic with blue arrows. Credit: NASA/Goddard/Adler/U. Chicago/Wesleyan.

The fate of Interstellar Probe is the hands of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, which prioritizes in its decadal studies where we are going in space exploration over ten year periods. We find out next year whether ISP has been selected among several strong candidates for the Decadal Survey for Solar and Space Physics (Heliophysics) 2024-2033. Until then, I continue to scout the literature both for Interstellar Probe as well as JPL’s Solar Gravitational Lens (SGL) mission, a candidate for the same study. These are huge decisions in space science.

Be aware of a new paper tackling the issues of heliospheric and dust science that a mission like Interstellar Probe could examine, with a solid backgrounder on the kind of instrumentation that would make this first dedicated interstellar probe a game-changer in our understanding of the local interstellar environment. The paper, by lead author Veerle J. Sterken (ETH Zürich) and colleagues, was originally submitted to the heliophysics Decadal, and is here available in a modified version (citation below) that includes the new instrumentation discussion among other modifications.

I won’t run through the entire paper; suffice it to say that its discussion of interstellar dust in and around the heliosphere is comprehensive and its analysis of how best to study changing environments in the interstellar medium is highly informative. The benefit of a probe explicitly designed to examine the transition between dust and gas states along its trajectory are clear. From the paper, which notes here the particular importance of heliopause passage:

ISP will fly throughout approximately 16 years, more than a solar cycle, while passing through interplanetary space, the termination shock, the heliosheath, up to the heliopause and beyond, making it an optimal mission for studying the heliosphere-dust coupling and using this knowledge for other astrospheres. Beyond the heliopause, the tiny dust with gyro-radii of only a few to 100 AU (for dust radii < 0.1 μm…), will help study the interstellar environment (magnetic field, plasma) and may detect local enhancements of smaller as well as bigger ISD [interstellar dust]. The strength of the mission lies in flying through all of these diverse regions with simultaneous magnetic field, dust, plasma and pickup ion measurements. No mission so far has flown a dedicated dust dynamics and composition suite into the heliosheath and the vast space beyond.

Analyzing the interaction between the heliosphere and interstellar dust acts as a probe into the history of our own Solar System, since we know that some of this material was affected by near-Earth supernovae, still raining down in the form of dust today. Mid-sized dust particles in the range of 0.1 to 0.6 μm in radius can make it through the heliosphere into the Solar System. Some smaller particles (30-100 nm) as well may escape filtering, but the authors note the limitations of our knowledge: “The exact lower cut-off size and time-dependence of particles that can enter the solar system is not yet exactly known, but Ulysses and Cassini already have measured ISD particles with radii between 50 and 100 nm.”

Thus we have markers for stellar and galactic evolution as factors in this study. But I’ll also remind those interested in interstellar flight that assessing dust density and the size distribution of particles will play a major role when we reach the point where we can send craft at a significant fraction of the speed of light. Larger particles in the local interstellar environment could cause catastrophic failure, while Ian Crawford has pointed out that other properties of this region could inform propulsion concepts like the interstellar ramjet.

Something else I learned from Ian Crawford (University of London) and wrote about twelve years ago (see Into the Interstellar Void) is that a spacecraft moving at 0.1c could make daily measurements 17 AU apart, which is roughly half the radius of the Solar System. So as we develop the fastest probe we can manage today in the form of designs like Interstellar Probe, we can see a larger picture in which such studies assist as we develop future technologies capable of actually making a crossing to Alpha Centauri, sampling widely along the way two different interstellar clouds and the boundary between them.

The paper is Sterken et al., “Synergies between interstellar dust and heliospheric science with an Interstellar Probe,” submitted as white paper for the National Academies Decadal Survey for Solar and Space Physics 2024-2033 and available as a preprint here.

Tidal Lock or Sporadic Rotation? New Questions re Proxima and TRAPPIST-1

Centauri Dreams regular Dave Moore just passed along a paper of considerable interest for those of us intrigued by planetary systems around red dwarf stars. The nearest known exoplanet of roughly Earth’s mass is Proxima Centauri b, adding emphasis to the question of whether planets in an M-dwarf’s habitable zone can indeed support life. From the standpoint of system dynamics, that often comes down to asking whether such a planet is not so close to its star that it will become tidally locked, and whether habitable climates could persist in those conditions. The topic remains controversial.

But there are wide variations between M-dwarf scenarios. We might compare what happens at TRAPPIST-1 to the situation around Proxima Centauri. We have an incomplete view of the Proxima system, there being no transits known, and while we have radial velocity evidence of a second and perhaps a third planet there, the situation is far from fully characterized. But TRAPPIST-1’s superb transit orientation means we see seven small, rocky worlds moving across the face of the star, and therein lies a tale.

The paper Dave sent, by Cody Shakespeare (University of Nevada Las Vegas) and colleague Jason Steffen, picks up on earlier work Shakespeare undertook that probes the differences between such scenarios. We know that conditions are right for a solitary planet, unperturbed by neighbors, to orbit with a spin rate synchronous with its orbital rate, the familiar ‘tidal lock.’ On such a world, we probe questions of climate, heat transport, the effects of an ocean and so on, to see if a planet with a star stationary in its sky could sustain life.

Image: This illustration shows what the TRAPPIST-1 system might look like from a vantage point near planet TRAPPIST-1f (at right). Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech.

But as TRAPPIST-1 shows us in exhilarating detail, multi planet systems are not uncommon around this type of star, and now we have to factor in mean motion resonance (MMR), where the very proximity of the planets (all well within a fraction of Mercury’s orbit of our Sun) means that these effects can perturb a particular planet out of its otherwise spin-orbit synchronization. Call this ‘orbital forcing,’ which breaks what would have been, in a single-planet system, a system architecture that would inevitably lead to permanent tidal lock.

The results of this breakage produce the interesting possibility that planets like TRAPPIST-1 e and f may retain tidal lock but exhibit sporadic rotation (TLSR). Indeed, another recent paper referenced by the authors, written by Howard Chen (NASA GSFC) and colleagues, makes the case that this state can produce permanent snowball states in the outer regions of an M-dwarf planetary system. What is particularly striking about TLSR is the time frame that emerges from the calculations. Consider this, from the Shakespeare paper:

The TLSR spin state is unique in that the spin behavior is often not consistently tidally locked nor is it consistently rotating. Instead, the planet may suddenly switch between spin behaviors that have lasted for only a few years or up to hundreds of millennia. The spin behavior can occasionally be tidally locked with small or large librations in the longitude of the substellar point. The planet may flip between stable tidally locked positions by spinning 180°so that the previous substellar longitude is now located at the new antistellar point, and vice versa. The planet may also spin with respect to the star, having many consecutive full rotations. The spin direction can also change, causing prograde and retrograde spins.

Not exactly a quiescent tidal lock! Note the term libration, which refers to oscillations around the rotational axis of a planet. What Shakespeare and Steffen are analyzing is the space between long-lasting rotation and pure tidal lock. Indeed, the authors identify a spin scenario within the TLSR domain they describe as prolonged transient behavior, or PTB. Here the planet moves back and forth in a ‘spin regime’ that is essentially chaotic, so that questions of habitability become fraught indeed. Instead of a persistent climate, which we usually assume when assessing these matters, we may be looking at multiple states of climate determined by present and past spin regimes, and their necessary adaptation to the ever changing spin state.

Such global changes are reminiscent, though for different reasons, of Asimov’s fabled story “Nightfall,” in which scientists on a world in a system with six stars must face the social consequences of a ‘night’ that only appears every few thousand years. For here’s what Shakespeare and Steffen say about a scenario in which TSLR effects kick in, a world that had been tidally locked long enough for the climate to have become stable. The scenario again involves TRAPPIST-1:

Such a planet in the habitable zone around a TRAPPIST-1-like star could have an orbital period of around 4-12 Earth days – the approximate orbital periods of T-1d and T-1g, respectively. Due to the TLSR spin state, this planet may, rather abruptly, start to rotate, albeit slowly – on the order of one rotation every few Earth years. The previous night side of the planet, which had not seen starlight for many Earth years, will now suddenly be subjected to variable heat with a day-night cycle lasting a few years. The day side would receive a similar abrupt change and the climate state that prevailed for centuries would suddenly be a spinning engine with momentum but spark plugs that now fire out-of-sync with the pistons. In this analogy, the spark plugs and the subsequent ignition of fuel correspond to the input of energy from starlight. The response of ocean currents, prevailing winds, and weather patterns may be quite dramatic.

Not an easy outcome to model in terms of climate and habitability. The authors use a modified version of an energy release modeling software called 1D EBM HEXTOR as well as a model called the Hab1 TRAPPIST-1 Habitable Atmosphere Intercomparison (THAI) Protocol as they analyze these matters. I send you to the paper for the details.

Science fiction writers take note – here is rich material for new exoplanet environments. Notice that the TLSR spin state is different from the one-way change that occurs when a rotating planet gradually becomes tidally locked over large timescales. This is a regime of sudden change, or at least it can be. The authors consider spin regimes lasting less than 100 Earth years, with the longest regimes (these are classified as ‘quasi-stable’) lasting for 900 years or more and perhaps reaching durations of hundreds of thousands of years. The point is that “TLSR planets are able to be in both long-term persistent regimes and PTB regimes -– where frequent transitions between behaviors are present.”

We learn that all tidally locked bodies experience libration to some degree even if no other bodies are found in the system being examined. Four spin regimes are found within the broader spin state TLSR. Tidal lock with libration can occur around the substellar point, as well as around the substellar or antistellar point, or as noted a planet may be induced into a slow persistent rotation. Much depends upon how long any one of these ‘continuous’ states lasts; given enough time, a stable climate could develop. The chaotic behavior of the fourth state, prolonged transient behavior (PTB), induces frequent transitions in spin. Such transitions would be expected to produce extreme changes in climate.

The spin history of a given system will depend upon that system’s architecture and the key parameters of each individual planet, an indication of the complexity of the analysis. What particularly strikes me here is how fast some of these changes can occur. Here’s a science fiction scenario indeed:

The more extreme change is in the temperature of different longitudes as the planet transitions from a tidally locked regime to a Spinning regime or after the planet flips 180 and remains tidally locked. Rotating planets experience temperature changes at the equator of 50K or more over a single rotation period. The exact effects require more robust climate models, like 3D GCMs [Global Circulation Model], to properly examine. However, using comparisons with climate changes on Earth, it is likely that erosion of land masses would increase and major climate systems would experience significant changes.

As if the issue of habitability were not complex enough…

The paper is Shakespeare & Steffen, “Day and Night: Habitability of Tidally Locked Planets with Sporadic Rotation,” in process at Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society and available as a preprint. The Chen paper referenced above is “Sporadic Spin-Orbit Variations in Compact Multi-planet Systems and their Influence on Exoplanet Climate,” accepted at Astrophysical Journal Letters (preprint).