Centauri Dreams

Imagining and Planning Interstellar Exploration

How a Super-Earth Would Change the Solar System

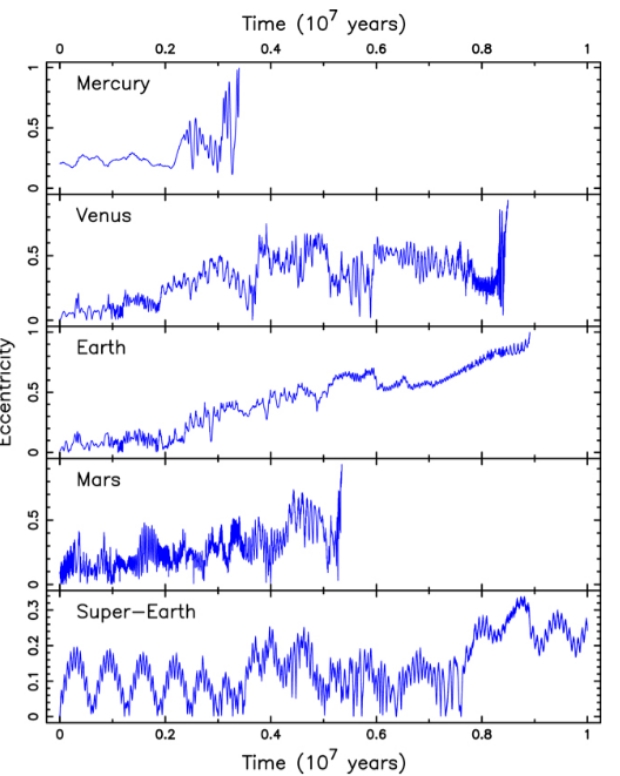

If there is a Planet Nine out there, I assume we’ll find it soon. That would be a welcome development, in that it would imply the Solar System isn’t quite as odd as it sometimes seems to be. We see super-Earths – and current thinking seems to be that this is what Planet Nine must be – in other stellar systems, in great numbers in fact. So it would stand to reason that early in its evolution our system produced a super-Earth, one that was presumably nudged into a distant, eccentric orbit by gravitational interactions.

The gap in size between Earth and the next planet up in scale is wide. Neptune is 17 times more massive than our planet, and four times its radius. Gas giant migration surely played a role in the outcome, and when considering stellar system architectures, it’s noteworthy as well that all that real estate between Mars and Jupiter seems to demand something more than asteroidal debris. To make sense of such issues, Stephen Kane (University of California, Riverside) has run a suite of dynamical simulations that implies we are better off without a super-Earth anywhere near the inner system.

Image: Artist’s concept of Kepler-62f, a super-Earth-size planet orbiting a star smaller and cooler than the sun, about 1,200 light-years from Earth. What effect would such a planet have in our own Solar System? Image credit: NASA Ames/JPL-Caltech/Tim Pyle.

Supposing a super-Earth did exist between Mars and Jupiter, Kane’s simulations demonstrated the outcomes for a range of different masses, the results presented in a new paper in the Planetary Science Journal. The heavyweight of our system, Jupiter’s 318 Earth masses carry profound gravitational significance for the rest of the planets. Disturb Jupiter, these results suggest, and in some scenarios the inner planets, including our own, are ejected from the Solar System. Even Uranus and Neptune can be affected and perhaps ejected as well depending on the super-Earth’s location.

As the paper notes, the range of possibilities is wide:

…several thousand simulations were conducted, producing a vast variety of dynamical outcomes for the solar system planets. The inner solar system planets are particularly vulnerable to the addition of the super-Earth planet, resulting in numerous regions of substantial system instability. The broad region of 2–4 au contains many locations of MMRs [Mean Motion Resonances] with the inner planets that further amplify the chaotic evolution of the inner solar system. There are also important MMR locations with the outer planets within the 2–4 au region, with potential significant consequences for the ice giants.

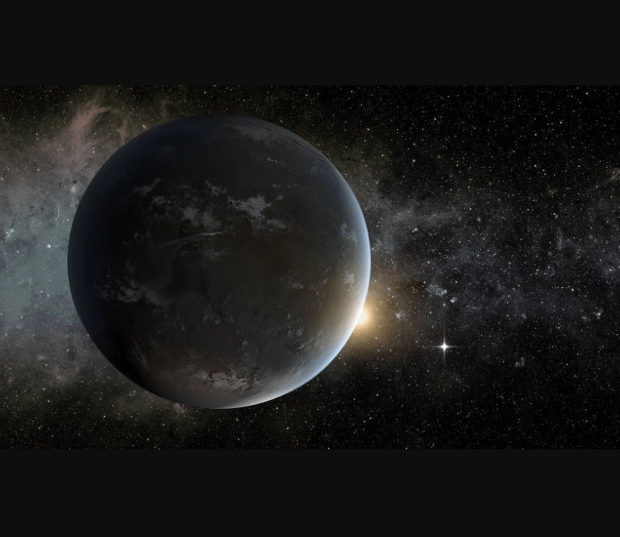

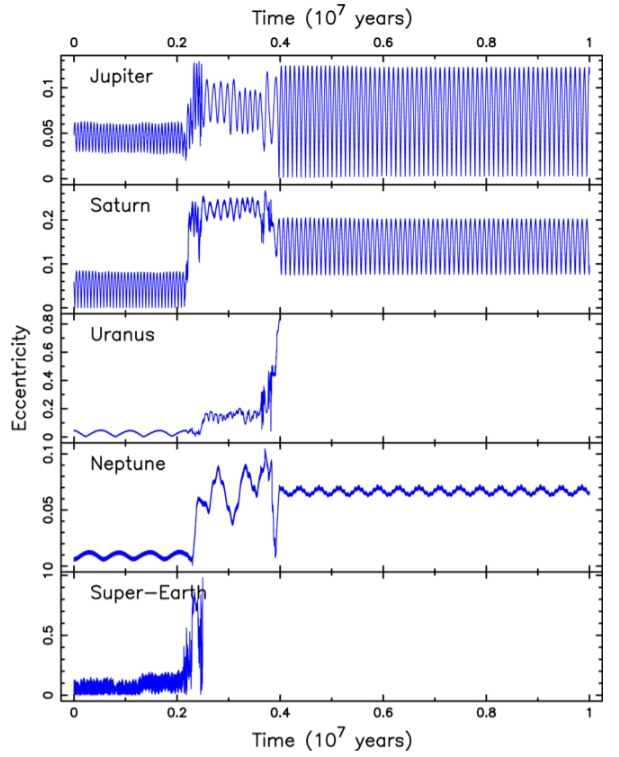

Let’s look at one possible outcome. The figure below shows the evolution in the eccentricity of the orbits of the inner planets in our Solar System, assuming a super-Earth with a mass of 7 times Earth’s and a semi-major axis of 2 AU. The simulation covers 107 years.

Image: This is Figure 2 from the paper. Caption: Eccentricity evolution of the solar system terrestrial planets (top four panels) for a 107 yr simulation, where the additional planet (bottom panel) has a mass and semimajor axis of 7.0 M? and 2.00 au, respectively. Credit: Stephen Kane.

The results show the devastating disruption this scenario produces. The orbits of the four inner planets become unstable over time, removing all of them from the system before the simulation concludes. Mars gets knocked out halfway through the simulation period, while Mercury is ejected early due to interactions with Venus and the Earth. The latter two planets see a gradual increase in their eccentricities. The semimajor axis of Venus increases as it decreases for Earth, creating close encounters and removing both worlds from the system 8 to 9 Myr after the simulation starts.

Different things happen, of course, as Kane manipulates the variables. Assuming a super-Earth with a mass eight times the Earth’s at 3.7 AU, the surprising result (surprising to me, at least) is that Mars remains largely unaffected, while it’s the super-Earth whose interactions with the outer planets become intense. The orbits of Venus and Earth begin to become more eccentric, with perturbations to the orbit of Mercury that eventually remove it from the system entirely. It’s fascinating to work through this paper to examine the various scenarios. Take a look at yet another possibility:

Image: This is Figure 8. Caption: Eccentricity evolution of the solar system outer planets (top four panels) for a 107 yr simulation, where the additional planet (bottom panel) has a mass and semimajor axis of 7.0 M? and 3.80 au, respectively. Credit: Stephen Kane.

Here we get Mean Motion Resonances with Jupiter and Saturn after about two million years, increasing the eccentricity of both, with the super-Earth ultimately being ejected from the system. Uranus is lost after about 4 million years and Neptune undergoes significant changes to its eccentricity. As Kane notes, the simulations show changes to system dynamics that are hugely sensitive to initial conditions, and in cases where significant interactions occur in the outer system, the orbits of the inner planets tend to become unstable as well. In the case of Figure 8, Mars is eventually ejected.

And this may have some bearing on our search for Planet Nine:

…the initial orbit for the additional planet was coplanar with Earth. Mutual inclinations between planetary orbits plays a role in overall system stability (Laskar 1989; Chambers et al. 1996), particularly for large inclinations (Veras & Armitage 2004; Correia et al. 2011), and may provide solutions to otherwise unstable architectures (Kane 2016; Masuda et al. 2020). It is therefore possible that there are orbital inclinations for the super-Earth that may reveal further locations of long-term stability, or else enhance unstable scenarios…

The paper implies, as the author adds in his conclusion, the “dynamical fragility” of the Solar System we have, with applications for the study of exoplanetary system architectures. How systems manage to work out sharing arrangements with super-Earths will doubtless become a key question for research as we move further into the era of space-based astrometry and learn more about how systems evolve.

The paper is Kane, “The Dynamical Consequences of a Super-Earth in the Solar System,” Planetary Science Journal Vol. 4, No. 2 (28 February 2023) 38 (full text).

DART’s Ejecta and Planetary Defense

I’m glad to see the widespread coverage of the DART mission results, both in terms of demonstrating to the public what is possible in terms of asteroid threat mitigation, and also of calming overblown fears that we have too little knowledge of where these objects are located. DART (Double Asteroid Redirection Test) was a surprisingly demonstrative success, shortening the orbit of the satellite asteroid Dimorphos by an unexpectedly large value of 33 minutes. The recoil effect from the ejection of asteroid material, perhaps as high as 0.5% of its total mass, accounts for the result.

Watching the ejecta evolve has been fascinating in its own right, as the interactions between the two elements of the binary asteroid come into play along with solar radiation pressure. Asteroids have previously been observed that displayed a sustained tail, as Dimorphos did after impact, and the DART results suggest that the hypothesis of similar impacts on these objects is correct. Thus we learn valuable lessons about how asteroids behave when impacted either by technologies or by natural objects. We can expect the study of ‘active asteroids’ to get a boost from the success of this mission.

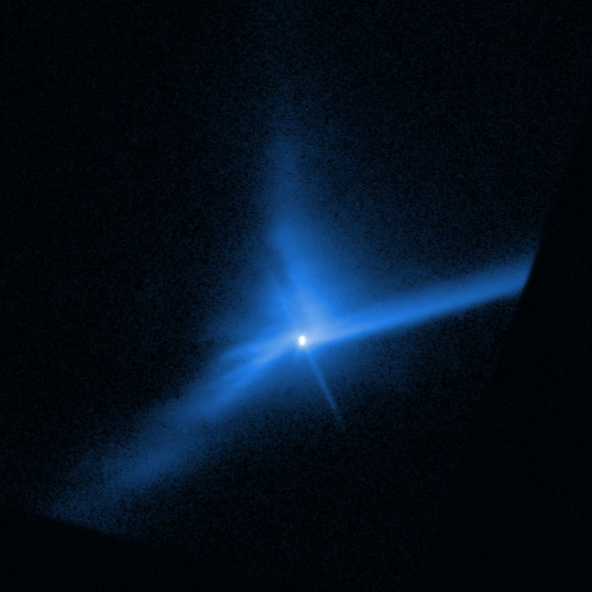

The two images below are from the Hubble instrument, which observed the development of Dimorphos’ tail. Jian-Yang Li (Planetary Science Institute) is lead author of a recent paper in Nature on the evolution of the ejecta. Li comments on the interplay between the gravity of Dimorphos and parent asteroid Didymos as well as the pressure of sunlight in the first two and a half weeks after the impact. Bear in mind that an impact on a single as opposed to a binary asteroid would not display such complex effects. The presence of Didymos was indeed useful:

“A simple way to visualize the evolution of the ejecta is to imagine a cone-shaped ejecta curtain coming out from Dimorphos, which is orbiting Didymos. After about a day, the base of the cone is slowly distorted by the gravity of Didymos first, forming a curved or twisted funnel in two to three days. In the meantime, the pressure from sunlight constantly pushes the dust in the ejecta towards the opposite direction of the Sun, and slowly modifies and finally destroys the cone shape. This effect becomes apparent after about three days. Because small particles are pushed faster than large particles, the ejecta was stretched towards the anti-solar direction, forming streaks in the ejecta.”

Image: Ejecta from Dimorphos 4.7 days (above) and 8.8 days (below) after impact, taken on October 1 and October 5, 2022, respectively. The Sun is at the 8 o’clock direction. The ejecta is pushed by the sunlight towards the 2 o’clock direction and increasingly stretched to form streaks. Credit: NASA, ESA, STScI, Jian-Yang Li (PSI), Image Processing: Joseph DePasquale.

So we’ve learned that slamming a 570 kilogram spacecraft into this type of asteroid at something over 22,000 kilometers per hour can alter its orbital speed. Data from the Light Italian CubeSat for Imaging of Asteroids (LICIACube) is part of the current analysis, while we’ll learn yet more about the effects of the impact from the European Space Agency’s Hera mission, which will survey both Didymos and Diomorphos, focusing on the crater left by DART and the changes to the mass of the impacted asteroid.

The matter of locating those hazardous asteroids that have yet to be identified is now highlighted by what we can consider the next planetary defense mission, the Near-Earth Object Surveyor, planned for a 2028 launch. The mission will carry a 50 centimeter diameter telescope operating at two infrared wavelengths, conducting a multi-year survey in search of near-Earth objects larger than 140 meters. The goal is to find 90 percent of such objects coming within 48 million kilometers of Earth’s orbit. The observation strategy employed should allow accurate enough determination of asteroid orbits to allow them to be found again and their trajectories tracked.

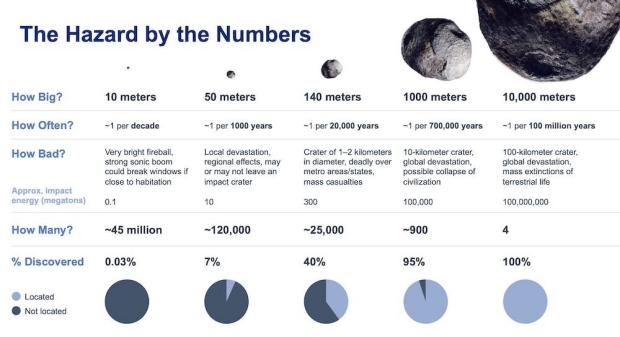

Image: Near-Earth asteroids and the possibilities of impact. Credit: NASA.

The paper on DART, one of five papers recently published in Nature on the mission, is Jian-Yang Li et al., “Ejecta from the DART-produced active asteroid Dimorphos,” Nature 01 March 2023 (abstract).

Re-thinking the Early Universe?

I hadn’t intended to return so quickly to the issue of high-redshift galaxies, but SPT0418-47 jibes nicely with last week’s piece on 13.5 billion year old galaxies as studied by Penn State’s Joel Leja and colleagues. In that case, the issue was the apparent maturity of these objects at such an early age in the universe.

Today’s work, reported in a paper in The Astrophysical Journal Letters, comes from a team led by Bo Peng at Cornell University. It too uses JWST data, in this case targeting a previously unseen galaxy the instrument picked out of the foreground light of galaxy SPT0418-47. In both cases, we’re seeing data that challenge conventional understanding of conditions in this remote era. This is evidence, but of what? Are we wrong about the basics of galaxy formation? Do we need to recalibrate the models we use to understand astrophysics at high-redshift?

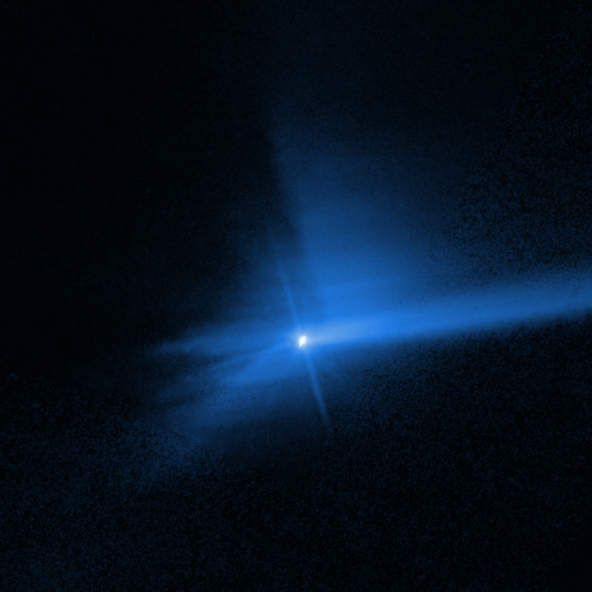

SPT0418-47 is the galaxy JWST was being used to study, an intriguing subject in its own right. This is an infant galaxy still forming stars in the early universe, observable through the bending of its light by a foreground galaxy to form an Einstein ring. In other words, we’re seeing gravitational lensing at work here, magnifying the young galaxy’s light, out of which information can be extracted about the primordial object. And within that light, astronomers have now found a second galaxy which manifested itself in two places in the ring.

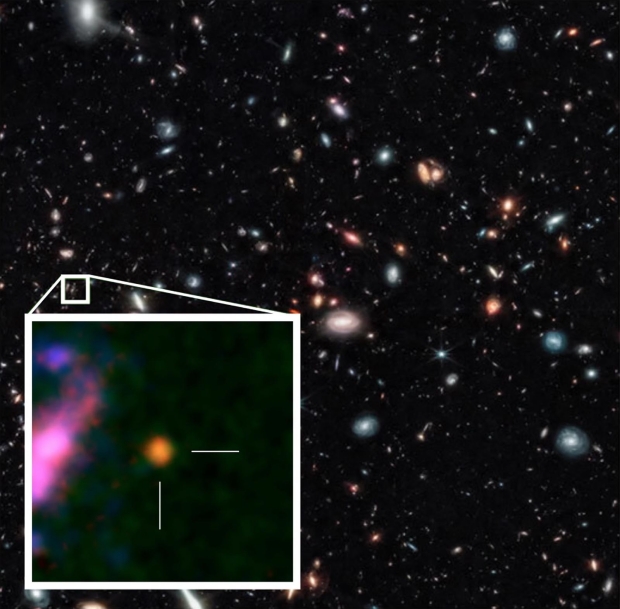

Image: This is Figure 1 from the paper. Caption: Figure 1. Left: H? pseudo-narrowband image of the SPT0418 system, averaged over the channels including the H? emission in the original spectral cube. The strongly lensed ring and the two newly discovered sources (SE-1 and SE-2) are highlighted by a red annulus and gray and black ellipses, marked as “A,” “B,” and “C,” respectively. The lensing galaxy is shown as the central bright source. The 835 ?m continuum is plotted as the thin black contours, with the levels 2, 4, 8, 16, 32 × ? where ? = 56.7 ?Jy beam ?1. Right: the spectra of the three sources integrated over the regions highlighted in the left panel, using the same color scheme. The spectrum for the ring is scaled by a factor of 0.1 for clarity. The small black bar below the H? line marks the wavelength coverage of the pseudo-narrowband image. The potentially detected lines are marked by vertical dotted lines. Credit: The Astrophysical Journal Letters (2023). DOI: 10.3847/2041-8213/acb59c.

ALMA (the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array) data could do no more than hint at the background galaxy’s existence, but working with spectral data from JWST’s NIRSpec instrument, Peng discovered the new light source within the Einstein ring. The unexpected find was a galaxy being gravitationally lensed by the same foreground galaxy that had made SPT0418-47 available for study, though considerably fainter.

What stands out here is the analysis of the chemical composition of the new galaxy’s light, which shows strong emission lines from hydrogen, nitrogen and sulfur atoms whose redshift showed the object to be about 10 percent of the age of the universe. The new galaxy, dubbed SPT0418-SE, appears to be close enough to SPT0418-47 that the two galaxies will interact with each other, making the duo a case study for galactic mergers. All of which is helpful, but here again we run into a fascinating problem. The newly discovered galaxy shows levels of metallicity comparable to our Sun.

It’s a conundrum. The Sun drew on earlier stellar generations to build up elements heavier than helium and hydrogen, and the Sun is roughly 4.6 billion years old. Amit Vishwas (Cornell Center for Astrophysics and Planetary Sciences) is second author on the paper:

“We are seeing the leftovers of at least a couple of generations of stars having lived and died within the first billion years of the universe’s existence, which is not what we typically see. We speculate that the process of forming stars in these galaxies must have been very efficient and started very early in the universe, particularly to explain the measured abundance of nitrogen relative to oxygen, as this ratio is a reliable measure of how many generations of stars have lived and died.”

But let’s turn back a minute, for we’re looking at two early galaxies, and it’s intriguing that SPT0418-47, the first of these, shows its own anomalies. Data from ALMA allow astronomers to see that although 12 billion years old, this object has a more mature structure than would be expected. No spiral arms are apparent, but a rotating disk and bulge are found, with stars packed tightly around the galactic center. Simona Vegetti (Max Planck Institute for Astrophysics), co-author on the 2020 paper on SPT0418-47 (citation below), had this to say three years ago:

“What we found was quite puzzling; despite forming stars at a high rate, and therefore being the site of highly energetic processes, SPT0418-47 is the most well-ordered galaxy disc ever observed in the early Universe. This result is quite unexpected and has important implications for how we think galaxies evolve.”

Image: Astronomers using the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), in which the European Southern Observatory (ESO) is a partner, have revealed an extremely distant and therefore very young galaxy that looks surprisingly like our Milky Way. The galaxy is so far away its light has taken more than 12 billion years to reach us: we see it as it was when the Universe was just 1.4 billion years old. It is also surprisingly unchaotic, contradicting theories that all galaxies in the early Universe were turbulent and unstable. This unexpected discovery challenges our understanding of how galaxies form, giving new insights into the past of our Universe. Credit: Rizzo et al./European Southern Observatory.

So the new galaxy, SPT0418-SE, adds to earlier evidence that the early universe was considerably less chaotic than we once thought. The new paper summarizes the issue with reference to the unexpectedly strong emission lines found in the data:

This spectroscopic study of a z > 4 galaxy opens up many questions, including the spatial arrangement and stellar/gas/metallicity distribution of the companion; the merging hypothesis of SPT0418-47; the dark-matter halo of the system; the overdensity of this potentially crowded field; reconciling the relatively high chemical abundances with the short formation time and the moderate stellar mass for the whole system; and interpreting the small [N ii] 122 and 205 ?m luminosities in the context of either a soft radiation field and/or a high N/O.

But again that note of high-redshift caution that I mentioned last week:

We attempt to reconcile the high metallicity in this system by invoking early onset of star formation with continuous high star-forming efficiency or by suggesting that optical strong line diagnostics need revision at high redshift. We suggest that SPT0418-47 resides in a massive dark-matter halo with yet-to-be-discovered neighbors.

Clearly scientists will be looking hard at how high-redshift targets are interpreted even as they continue to hypothesize about astrophysical mechanisms and star formation efficiency to explain seemingly mature objects at this early era. The game is afoot, as Sherlock Holmes used to say, and we’re a long way from reaching firm conclusions. The data are going to start coming fast and furious as we keep mining JWST and using ALMA to examine the universe in this early stage, as witness the image below, which I found just this morning. It shows us another remarkable object.

Image: The radio telescope array ALMA has pin-pointed the exact cosmic age of a distant JWST-identified galaxy, GHZ2/GLASS-z12, at 367 million years after the Big Bang. ALMA’s deep spectroscopic observations revealed a spectral emission line associated with ionized Oxygen near the galaxy, which has been shifted in its observed frequency due to the expansion of the Universe since the line was emitted. This observation confirms that the JWST is able to look out to record distances, and heralds a leap in our ability to understand the formation of the earliest galaxies in the Universe. Credit: NASA / ESA / CSA / T. Treu, UCLA / NAOJ / T. Bakx, Nagoya U.

The paper is Bo Peng et al., “Discovery of a Dusty, Chemically Mature Companion to a z ? 4 Starburst Galaxy in JWST ERS Data,” The Astrophysical Journal Letters 944 No. 2 L36 (17 February 2023). Full text. The paper on SPT0418-47 is Rizzo et al., “A dynamically cold disk galaxy in the early Universe,” Nature 584 (12 August 2020), pp. 201–204. Abstract. The GHZ2/GLASS-z12 paper is Bakx et al., “Deep ALMA redshift search of a z 12 GLASS-JWST galaxy candidate,” Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society Volume 519, Issue (4 March 2023), pp. 5076–5085 (abstract).

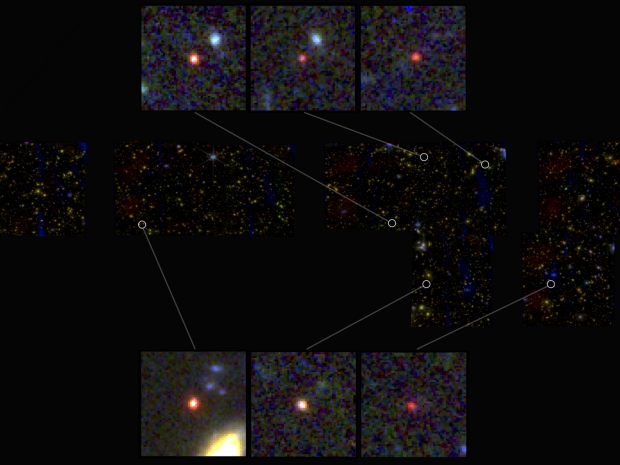

High Redshift Caution

When something turns up in astronomical data that contradicts long accepted theory, the way forward is to proceed with caution, keep taking data and try to resolve the tension with older models. That would of course include considering the possibilities of error somewhere in the observations. All that is obvious enough, but a new paper on JWST data on high-redshift galaxies is striking in its implications. Researchers examining this primordial era have found six galaxies, from no more than 500 to 700 million years after the Big Bang, that give the appearance of being massive.

We’re looking at light from objects 13.5 billion years old that should be anything but mature, if compact, galaxies. That’s a surprise, and it’s fascinating to see the scrutiny to which these findings have been exposed. The editors of Nature have helpfully made available a peer review file containing back and forth comments between the authors and reviewers that give a jeweler’s eye look at how intricate the taking of high-redshift measurements can be. Reading this material offers an inside look at how the scientific community tests and refines its results enroute to what may need to be a modification of previous models.

It’s the availability of that peer review file that, as much as the findings themselves, occasions this post, as it offers laymen like myself a chance to see the scientific publication process at work. That cannot be anything but salutary in an era when complicated ideas are routinely pared into often misleading news headlines.

Image: Images of six candidate massive galaxies, seen 500-700 million years after the Big Bang. One of the sources (bottom left) could contain as many stars as our present-day Milky Way, according to researchers, but it is 30 times more compact. Credit: NASA, ESA, CSA, I. Labbe (Swinburne University of Technology). Image processing: G. Brammer (Niels Bohr Institute’s Cosmic Dawn Center at the University of Copenhagen). All Rights Reserved.

One note of caution emerges in the abstract to this work: “If verified with spectroscopy, the stellar mass density in massive galaxies would be much higher than anticipated from previous studies based on rest-frame ultraviolet-selected samples.”

That’s a pointer to what seems to be needed next. Penn State’s Joel Leja modeled the light from these objects, and I like the openness to alternative explanations that he injects here:

“This is our first glimpse back this far, so it’s important that we keep an open mind about what we are seeing. While the data indicates they are likely galaxies, I think there is a real possibility that a few of these objects turn out to be obscured supermassive black holes. Regardless, the amount of mass we discovered means that the known mass in stars at this period of our universe is up to 100 times greater than we had previously thought. Even if we cut the sample in half, this is still an astounding change.”

So the question of mass looms just as large as the formation process even if these do not turn out to be galaxies. No wonder Leja says the research team has been calling the six objects ‘universe breakers.’ On the one hand, the question of mass gets into fundamental issues of cosmology and the models that have long served astronomers. If galaxies actually form at this level at such an early time in the universe, then the mechanisms of galaxy formation demand renewed scrutiny. Leja is suggesting that a spectrum be produced for each of the new objects that can confirm the accuracy of our distance measurements, and also demonstrate what these ‘galaxies’ are made up of.

The paper on this remarkable finding itself continues to evolve. It’s Labbé et al., “A population of red candidate massive galaxies ~600 Myr after the Big Bang.” Nature 22 February 2023 (abstract). Note this editorial comment from the abstract page: “We are providing an unedited version of this manuscript to give early access to its findings. Before final publication, the manuscript will undergo further editing.” I’d like to read that final edit before commenting any further.

How Common Are Planets Around Red Dwarf Stars?

We’re beginning to learn how common planets are around stars of various types, but M-dwarfs get special attention given their role in future astrobiological studies. As I’ve just been talking about CARMENES, the Calar Alto high-Resolution search for M dwarfs with Exoearths with Near-infrared and optical Échelle Spectrographs program, I’ll fold in today’s news about their release of 20,000 observations covering more than 300 stars, for we can mine some data here about planet occurrence rates.

59 new planets turn up in the spectroscopic data gathered at the Calar Alto Observatory in Span, with about 12 thought to be in the habitable zone of their star. I’ll await with interest our friend Andrew LePage’s assessment. His habitable zone examinations serve as a highly useful reality check.

I mentioned spectrographic data above. The CARMENES instruments are built for optical as well as near-infrared studies, and have been used to explore nearby red dwarfs and their possible planets since 2015. The original project ended at the end of 2020, covering the data released here, although later observations are continuing, so we can expect further releases. Remember, this is radial velocity rather than transit work. CARMENES offers an accuracy of about 1 meter per second, meaning astronomers can measure the tiny motions induced by an orbiting planet with that degree of sensitivity. At this level, low-mass stars yield up Earth-sized planets.

The new CARMENES planets appear in the graphic below, drawn from publication of the project’s first large dataset as published in Astronomy & Astrophysics. 19,633 spectra for a sample of 362 targets were collected. The current paper covers only the visible-light data, with the infrared data to be made public when processing is complete. CARMENES has now observed about half of all nearby red dwarfs, limited of course by the fact that its location in Spain precludes southern hemisphere observations. A bit more on the original 362 target stars:

The sample was designed to be as complete as possible by including M dwarfs observable from the Calar Alto Observatory with no selection criteria other than brightness limits and visual binarity restrictions. To best exploit the capabilities of the instrument, variable brightness cuts were applied as a function of spectral type to increase the presence of late-type targets. This effectively leads to a sample that does not deviate significantly from a volume-limited one for each spectral type. The global completeness of the sample is 15% of all known M dwarfs out to a distance of 20 pc and 48% at 10 pc.

Image: An animated illustration of the CARMENES planets. All planets discovered with the same method as CARMENES, but with other instruments, are shown as grey dots. With the data collected in the period 2016-2020, CARMENES has discovered and confirmed 6 Jupiter-like planets (with masses more than 50 times that of the Earth), 10 Neptunes (10 to 50 Earth masses) and 43 Earths and super-Earths (up to 10 Earth masses). The vertical axis indicates what star type the planets orbit around, from the coolest and smallest red dwarfs to brighter and hotter stars (the Sun would correspond to the second from the top). The horizontal axis depicts the distance from the planet to the star by showing the time it takes to complete the orbit. Planets in the habitable zone (blue-shaded area) can harbor liquid water on their surface. Credit: © Institut d’Estudis Espacials de Catalunya (IEEC).

As to the title of today’s post, the authors have calculated new planet occurrence rates from a subset of the overall sample, with low-mass planets tagged at 1.06 planets per star in periods of 1 day to 100 days, “and an overabundance of short-period planets around the lowest-mass stars of our sample compared to stars with higher masses.” Nearly every M-dwarf, in other words, appears to host at least one planet. The long-period giant planet occurrence rate comes in at 3%.

CARMENES Legacy Plus, which continues the original project, began in 2021 and continues to observe the same stars at least until the end of this year. Juan Carlos Morales is a researcher at IEEC (Institut d’Estudis Espacials de Catalunya):

“In order to determine the existence of planets around a star, we observe it a minimum of 50 times. Although the first round of data have already been published to grant access to the scientific community, the observations are still ongoing.”

The paper is Ribas et al., “The CARMENES search for exoplanets around M dwarfs Guaranteed time observations Data Release 1 (2016-2020),” Astronomy & Astrophysics Vol. 670, A139 (22 February 2023). Full text.

Uranus Orbiter and Probe: Implications for Icy Moons

What do you get if you shake ice in a container with centimeter-wide stainless steel balls at temperature of –200 ?C? The answer is a kind of ice with implications for the outer Solar System. I just ran across an article in Science (citation below) that describes the resulting powder, a form of ‘amorphous ice,’ meaning ice that lacks the familiar crystalline arrangement of regular ice. There is no regularity here, no ordered structure. The two previously discovered types of amorphous ice – varying by their density – are uncommon on Earth but an apparently standard constituent of comets.

The new medium-density amorphous ice may well be produced on outer system moons, created through the shearing process that the researchers, led by Alexander Rosu-Finsen at University College London, produced in their lab work. There is a good overview of this water ‘frozen in time’ in a recent issue of Nature. The article quotes Christoph Salzmann (UCL), a co-author on the Science paper:

The team used a ball mill, a tool normally used to grind or blend materials in mineral processing, to grind down crystallized ice. Using a container with metal balls inside, they shook a small amount of ice about 20 times per second. The metal balls produced a ‘shear force’ on the ice, says Salzmann, breaking it down into a white powder.

Firing X-rays at the powder and measuring them as they bounced off — a process known as X-ray diffraction — allowed the team to work out its structure. The ice had a molecular density similar to that of liquid water, with no apparent ordered structure to the molecules — meaning that crystallinity was “destroyed”, says Salzmann. “You’re looking at a very disordered material.”

Disruptions in icy surfaces caused by the process would have implications for the interface between ice and liquid water that is presumed to exist on moons like Europa and Enceladus. The surface might be given to disruptions that would expose ocean beneath.

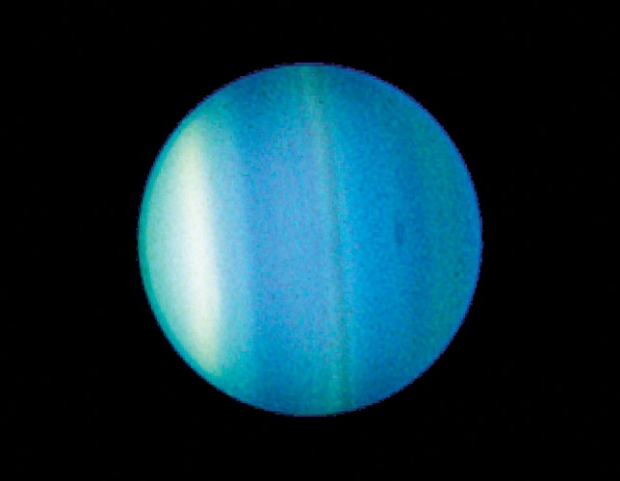

What goes on in the icy moons of the outer system is always of interest, especially given the astrobiological possibilities, and it was probably the thought of an ice giant orbiter at Uranus that triggered my interest in the amorphous ice issue. Kathleen Mandt (Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory) just wrote the former up in Science as well, noting how little we’ve learned since the solitary Voyager flyby of the planet in 1986. In addition to planetary structure and atmosphere, we could do with a lot more information about its moons and their possible liquid water oceans.

Image: This 2006 image taken by the Hubble Space Telescope shows bands and a new dark spot in Uranus’ atmosphere. Credit: NASA/Space Telescope Science Institute.

The planetary science decadal survey released in 2022, called Origins, Worlds, and Life, which reviewed over 500 white papers and 300 presentations over the course of its 176 meetings, flagged the need for such a mission in the coming decade, a planetary flagship mission as a next step forward after Europa Clipper. I don’t want to downplay the role of such a mission in deepening our understanding of ice giant formation and migration, not to mention the Uranian atmosphere, but the moon system here has proven an extreme challenge for observers. Its study becomes a major driver for the Uranus Orbiter and Probe (UOP) mission:

The system’s extreme obliquity…limits visibility of the moons to one hemisphere during southern and northern summers. Voyager 2 could only image the moons’ southern hemispheres, but what was seen was unexpected. The five largest moons, predicted to be cold dead worlds, all showed evidence of recent resurfacing, suggesting that geologic activity might be ongoing. One or more of these moons could have potentially habitable liquid water oceans under an ice shell, making them “ocean worlds.” Ariel, the most extensively resurfaced moon, is a strong ocean worlds candidate along with the two largest moons, Titania and Oberon… UOP will image and measure the composition of the full surfaces of the moons to search for ongoing geologic activity, and measure whether magnetic fields vary in their interiors owing to the presence of liquid water.

Miranda, Ariel, Umbriel, Titania and Oberon, the five largest moons of Uranus, could all contain subsurface oceans (and I don’t want to leave out of the UOP story the fact that it would carry a Uranus atmospheric probe designed to reach a depth of at least 1 bar in pressure, a fascinating investigation in itself). The decadal survey has recommended a launch by 2032 to take advantage of a Jupiter gravity assist that would allow arrival before the northern autumn equinox in 2050 for better study of the moon system. “The space science community has waited more than 30 years to explore the ice giants,” writes Mandt, “and missions to them will benefit many generations to come.”

The first of today’s papers is Rosu-Finsen et al., “Medium-density amorphous ice,” Science Vol. 379, No. 6631 (2 February 2023), pp. 474-478 (abstract). The Mandt article is “The first dedicated ice giants mission,” Science Vol. 379, No. 6633 (16 February 2023), pp. 640-642 (full text).