Centauri Dreams

Imagining and Planning Interstellar Exploration

Redefining the Galactic Habitable Zone

To understand the Solar System’s past and to tighten our parameters for SETI searches, we need to consider habitability not only as a planetary and stellar phenomenon but a galactic one as well. The Milky Way is a highly differentiated place, its core jammed with older stars and Sagittarius A*, which is almost certainly a supermassive black hole. The gorgeous spiral arms spawn new stars while the globular clusters in the halo house ancient clusters. Where in all this is life most likely to form? And perhaps more to the point, in what ways do stars and their associated planets migrate in the galactic disk?

Our Sun raises the issue by virtue of the fact that its metallicity, as measured by the ratio of iron to hydrogen (Fe/H), is higher than nearby stars that are of a similar age. In a new paper from Junichi Baba (Kagoshima University) and colleagues at the National Observatory of Japan and Kobe University, the authors offer this as evidence that the Solar System formed closer to the galactic center. The difference is large: Estimates using the metallicity of the galactic disk over time place the Sun’s formation at an average of 5 kiloparsecs from the center, migrating to its current position 8.2 kpc out (a kiloparsec is 3261.56 light years).

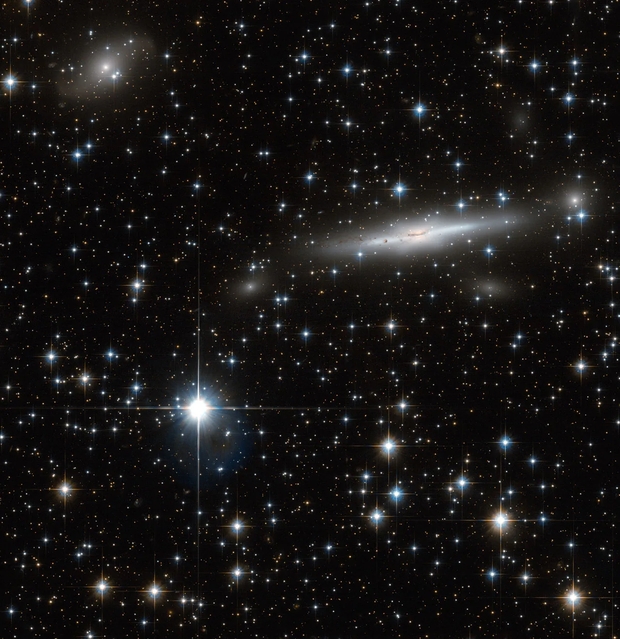

Features like the ‘galactic bar,’ an elongated formation of stars and star-forming material, as well as the spiral arms so evident in photographs of spiral galaxies, have much to say about the dynamics of the galaxy at large. The bar is thought to have been present when the Sun formed, and earlier papers have considered that the Sun likely originated in a place where the effects of the galactic bar would have been pronounced. Our star evidently migrated outward despite its location within the galactic bar. Modeling the energies at work within this co-rotating frame allows the authors to investigate the question of habitable orbits being modulated by this dynamic system.

Image: This image from the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope shows the broad and sweeping spiral galaxy NGC 4731. It lies in the constellation Virgo and is located 43 million light-years from Earth. The image uses data collected from six different filters. The abundance of color illustrates the galaxy’s billowing clouds of gas, dark dust bands, bright pink star-forming regions and, most obviously, the long, glowing bar with trailing arms. Barred spiral galaxies outnumber both regular spirals and elliptical galaxies put together, numbering around 60% of all galaxies. The visible bar structure is a result of orbits of stars and gas in the galaxy lining up, forming a dense region that individual stars move in and out of over time. Credit: ESA/Hubble & NASA, D. Thilker.

These stellar movements are important because they would have led to changes in the surrounding environments of the Solar System and thus affect planetary habitability.

One way is through radiation hazards, which change over time. From the paper:

We examine how the solar system’s migration through the Milky Way has altered radiation hazards, focusing specifically on the star formation rate (SFR) density and GRB event rates, both of which significantly influence planetary habitability. High SFRs are associated with frequent supernovae, as massive stars rapidly reach the end of their lifetimes. These supernovae can substantially impact their surrounding environments, especially through lethal GRBs. GRBs are divided into two types: short-duration GRBs (SGRBs), originating from compact object mergers (E. Berger 2014) and common in older stellar populations, and long-duration GRBs (LGRBs), resulting from massive star collapses (S. E. Woosley & J. S. Bloom 2006) in star-forming regions. Both types of GRBs pose significant risks to life by exposing planets to intense high-energy radiation.

Although the authors don’t probe deeply in the direction of giant molecular clouds, they do note that the work of other astronomers shows that stars moving through the galactic plane closer to galactic center encounter more of these, meaning that they are exposed to supernovae on a more frequent basis. Another factor I find intriguing is the number of comets entering the planetary region of the Solar System, which clearly would affect the supply of life-building materials. Tidal forces from the galaxy itself and encounters with other stars would disrupt the orbits of long-period comets in the Oort Cloud. Rich in prebiotic molecules and organic materials, these clearly affect the conditions for life to develop on a planetary surface.

The modeling in this paper shows that stars born in the same region can experience “vastly different environments for the habitability and evolution of planetary systems” as they follow different orbital migration paths. Scientists have previously considered a galactic habitable zone in terms of distance from the center, but to my knowledge this is the first attempt to model and quantify the effects of the migration of entire stellar systems. In other words, we need to abandon the idea of fixed ‘zones’ of habitability and think in terms of stellar movement rather than regions.

What emerges here is the new term I referenced above: galactic habitable orbits. These are:

…pathways through the Milky Way offering varying conditions for life’s development based on evolving galactic dynamics. By considering the dynamical effects of the Galactic bar and spiral arms, we can better understand habitability in the Galactic context. Examining the differences in radiation environments and the supply of life-building materials encountered along different migration pathways provides a more nuanced understanding of how the dynamic nature of the Milky Way impacts planetary habitability.

Obviously habitability discussions begin first with criteria based on life’s development on Earth, which only makes sense given that we have only this example to work with. Whether similar mechanisms are at play in other stellar systems is something we’re only beginning to learn as we investigate exoplanet atmospheres in search of biosignatures. So it’s clear that this early discussion of galactic habitability will be enriched with time as we learn if there are other pathways to supporting life. But the overall contribution is clear. Think in terms of dynamic orbits rather than static zones for life to develop in a galaxy that is in incessant motion and possible astrobiological evolution.

The paper is Baba et al., “Solar System Migration Points to a Renewed Concept: Galactic Habitable Orbits,” The Astrophysical Journal Letters Vol. 976, No. 2 (26 November 2024), L 29 (full text). You might also find Galactic Habitability and Sgr A* interesting. It’s an article I wrote in 2018 covering Balbi and Tombesi, “The habitability of the Milky Way during the active phase of its central supermassive black hole,” Scientific Reports 7, article #: 16626 (2017). Full text. And I have to add Charles Lineweaver’s seminal discussion of galactic habitability in “The Galactic Habitable Zone and the Age Distribution of Complex Life in the Milky Way,” Science Vol. 303, No. 5654 (2 January 2004), pp. 59-62, with abstract here.

Can Life Emerge around a White Dwarf?

My curiosity about white dwarfs continues to be piqued by the occasional journal article, like a recent study from Caldon Whyte and colleagues reviewing the possibilities for living worlds around such stars. Aimed at Astrophysical Journal Letters, the paper takes note of the expansion of the search space from stars like the Sun (i.e., G-class) in early thinking about astrobiology to red dwarfs and even the smaller and cooler brown dwarf categories. Taking us into white dwarf territory is exciting indeed.

How lucky to live in a time when our technologies are evolving fast enough to start producing answers. I sometimes imagine what it would have been like to have been around in the great age of ocean discovery, when a European port might witness the arrival of a crew with wondrous tales of places that as yet were on no maps. Today, with Earth-based instruments like the Extremely Large Telescope, the Giant Magellan Telescope and the Vera Rubin Observatory, we can expect data from near-ultraviolet to mid-infrared to complement what space telescopes like the Nancy Grace Roman instrument, not to mention the Habitable Worlds Telescope, will eventually tell us.

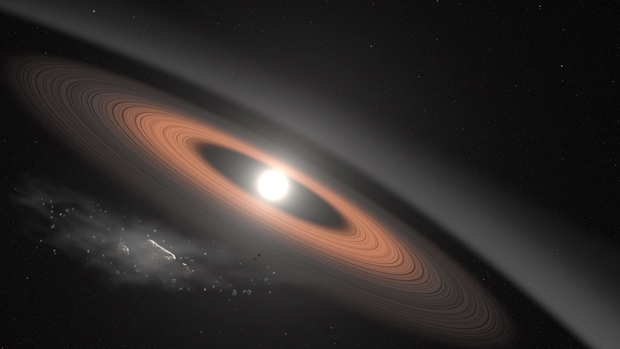

These instruments aren’t that far from completion, so the process of prioritizing stellar systems is crucial, given that we have thousands of exoplanets to deal with. Whyte and team (Florida Institute of Technology), working with Paola Pinilla (University College, London) point out that while we’ve neglected white dwarfs in terms of astrobiology, there are reasons for reassessing the category. Sure, a white dwarf is a stellar remnant, having blown off mass in its red giant phase and disrupted any existing planetary system. But around many white dwarfs circumstellar material may allow the formation of new planets, as is illustrated in the image below. And if such planets form, the possibilities for life are intriguing.

Image: In this illustration, an asteroid (bottom left) breaks apart under the powerful gravity of LSPM J0207+3331, the oldest, coldest white dwarf known to be surrounded by a ring of dusty debris. Scientists think the system’s infrared signal is best explained by two distinct rings composed of dust supplied by crumbling asteroids. Credit: NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center/Scott Wiessinger.

After all, a white dwarf offers a long lifetime for biological life to emerge. Based on studies using luminosity to estimate star lifetimes, it appears that almost all the white dwarfs in the 0.6 solar mass range (typical for the category, although lower-mass dwarfs have been observed) are less than 10 billion years old. As long as accretion keeps their mass below the Chandrasekhar limit (around ~1.4 solar masses), they’re stabilized by electron degeneracy pressure and continue cooling for billions of years. Interestingly, 97 percent of all stars in the Milky Way will become white dwarfs. I’m drawing that figure, which surprised me, from a 2001 paper called “The Potential of White Dwarf Cosmochronology” (citation below), but I see Whyte and team use the same number. The 2001 paper is by Fontaine, Brassard and Bergeron, from which this:

…white dwarf stars represent the most common endpoint of stellar evolution. It is believed that over 97% of the stars in the Galaxy will eventually end up as white dwarfs. The defining characteristic of these objects is the fact that their mass is typically of the order of half that of the Sun, while their size is more akin to that of a planet. Their compact nature gives rise to large average densities, large surface gravities, and low luminosities.

In the near future, I want to dig into this further. Because red dwarfs, 80 percent of the galaxy, live a long, long time. How much do we really know about what their ultimate fate will be? Looking around in this epoch, all we see are red dwarfs in their comparative infancy.

But back to dwarfs of the white variety. Remember how small these stars are. 0.6 solar masses corresponds to a radius of 1.36 times that of Earth. We get terrific transit depth, but as always the odds favor detecting larger planets. The low luminosity of a white dwarf means the habitable zone is going to be close to the star, but we know little about how an existing stellar system fares as its star undergoes the red giant phase. Would planets be cleared out of this region?

Observations by our latest instruments will better inform us about the stellar dynamics at work here. But let me quote the paper for the good news about habitable zones:

…a major challenge to planetary habitability for such a system is the inward migration of the habitable zone. After the white dwarf is formed, it rapidly cools until it is between 2 and 4 Gyr old, where the cooling slows down…, remaining stable until it attains an age of at least 8 Gyr. This creates a range of orbital distances where there are billions of years between the time the planet would enter the habitable zone and when it would leave it, which we refer to as the habitable lifetime. Another promising result from this habitable zone is that its width seems to remain constant as the star ages until the end of its habitable lifetime, which is understood to manifest when it is cut-off by the Roche limit. This period of stability creates a window of time for life to begin and evolve that is very similar in duration to that of Earth’s own habitability interval.

The authors consider the maximum habitable lifetime for a white dwarf to be about 7 billion years. Assume that it takes a billion years for life to emerge, then the paper’s numbers show that an Earth-class planet with a constant orbital distance between ∼ 0.006 AU and ∼ 0.06 AU would remain in the habitable zone and offer conditions that would support liquid water on the surface. The former figure is the Roche limit, which sets the limit on how close a planet can orbit a star without being torn apart by tidal forces. Get too close and a planet breaks into what we will see as a debris disk. Contrast this 7 billion years with the emergence of life on Earth at 0.8 billion years, and the the appearance of a tool-using technological species some 3.7 billion years after that.

Plenty of time exists, in other words, for interesting things to happen. We also have to factor in the presence of an atmosphere, whose constitution will vary the inner and outer limits of the habitable zone. Remember that we are dealing with a star that is gradually cooling, so factors that lead to more warming will be beneficial. The problem at this point is that the specifics of a white dwarf’s effects upon a planetary atmosphere are not well understood, and I’m not sure I’ve even seen them modeled.

The James Webb Space Telescope should help in expanding our knowledge of these factors, and may also explain why so few planets have been found around white dwarfs thus far. Earlier work has indicated that the transit probabilities for an Earth-class exoplanet around a white dwarf are a slim 0.006, further compromised by the size and luminosity of white dwarfs. Planets in the tight habitable zone of such a star would surely have been destroyed during the red giant phase, but studies of white dwarf atmospheric pollution are encouraging. They indicate that the formation of new close-in planets out of a circumstellar debris disk is a distinct possibility.

This is an exciting paper that paints a serious upside for habitability around a kind of star that has seldom been examined in this context. Thus the conclusion:

The effective temperature of a typical white dwarf during its habitable lifetime provides conditions for abiogenesis and photosynthesis similar to those seen on Earth. Moreover, the habitable lifetime could be slightly longer than the Sun’s at the ideal orbital distance of 0.012 AU. With a long habitable lifetime and overlap in PAR [photosynthetically active radiation] and abiogenesis zones white dwarfs are an ideal host for the origin and advanced evolution of life.

The paper is Whyte et al., “Potential for life to exist and be detected on Earth-like planets orbiting white dwarfs,” accepted at Astrophysical Journal Letters (preprint). The 2001 paper cited within the text is Fontaine, Brassard & Bergeron, “The Potential of White Dwarf Cosmochronology,” Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific Vol. 113, No. 782 (2001), 409 (full text). See also Saumon et al. for a more recent look at the question: “Current challenges in the physics of white dwarf stars,” Physics Reports Volume 988 (19 November 2022), 1-63 (abstract).

Autumn Among the Galaxy Clusters

The idea of moving stars as a way of concentrating mass for use by an advanced civilization – the topic of recent posts here – forces the question of whether such an effort wouldn’t be observable even by our far less advanced astronomy. In his paper on life’s response to dark energy and the need to offset the accelerating expansion of the cosmos, Dan Hooper analyzed the possibilities, pointing out that cultures billions of years older than our own may already be engaged in such activities. Can we see them?

I like Centauri Dreams reader Andrew Palfreyman’s comment that what astronomers know as the ‘Great Attractor’ is conceivably a technosignature, “albeit on a scale somewhat more grand than that cited.” An interesting thought! And sure, as some have pointed out, nudging these concepts around on a mental chess board is wildly speculative, but in the spirit of good science fiction, I say why not? We have a universe far older than our own planet with possibilities we might as well imagine.

If we turn our attention in the general direction of the constellation Centaurus and then look not at the paltry 4.3 light year distance of Alpha Centauri but 150–250 million light years from Earth, we encounter a region of mass concentration that folds within the Laniakea Supercluster. The latter is galactic structure at an extraordinary level, as it takes in some 100,000 galaxies including the Virgo Supercluster, and that means it takes in the Local Group and the Milky Way as well.

What’s happening is that this hard to observe region (it’s blocked by our own galaxy’s gas and dust) is evidently drawing many galaxies including the Milky Way towards itself. The speed of this motion is about 600 kilometers per second. Bear in mind that the Shapley Supercluster lies beyond the Great Attractor and is also implicated in the motion of galaxies and galaxy clusters in this direction. So the science fictional scenario has a civilization clustering matter at the largest scale to avoid the effects of the accelerating expansion that will eventually cut off anything that is not gravitationally bound. Cluster enough stars and you maintain your energy sources.

Image: Located on the border of Triangulum Australe (The Southern Triangle) and Norma (The Carpenter’s Square), this field covers part of the Norma Cluster (Abell 3627) as well as a dense area of our own galaxy, the Milky Way. The Norma Cluster is the closest massive galaxy cluster to the Milky Way, and lies about 220 million light-years away. The enormous mass concentrated here, and the consequent gravitational attraction, mean that this region of space is known to astronomers as the Great Attractor, and it dominates our region of the Universe. The largest galaxy visible in this image is ESO 137-002, a spiral galaxy seen edge on. In this image from Hubble, we see large regions of dust across the galaxy’s bulge. What we do not see here is the tail of glowing X-rays that has been observed extending out of the galaxy — but which is invisible to an optical telescope like Hubble. Credit: ESA/Hubble & NASA.

Recall the parameters of Dan Hooper’s paper, which posits the collection of stars in the range of 0.2 to 1 solar mass as the most attractive targets. The constraint is needed because high-mass stars will have lifetimes too short to make the journey (Hooper posits 0.1 c as the highest velocity available) to the collection zone. The idea is that the civilization will enclose lower-mass stars in something like Dyson Spheres, using these to collect the energy needed for propulsion of the stars themselves. Not your standard Dyson Sphere, but astronomical objects using propulsion that may be detectable.

Hooper doesn’t wade too deep into these waters, but here’s his thought on technosignatures:

From our vantage point, such a civilization would appear as a extended region, tens of Mpc in radius, with few or no perceivable stars lighter than approximately ∼2M☉ (as such stars will be surrounded by Dyson Spheres). Furthermore, unlike traditional Dyson Spheres, those stars that are currently en route to the central civilization could be visible as a result of the propulsion that they are currently undergoing. The propellant could plausibly take a wide range of forms, and we do not speculate here about its spectral or other signatures. That being said, such acceleration would necessarily require large amounts of energy and likely produce significant fluxes of electromagnetic radiation.

This is a different take on searching for Dyson Spheres than has been employed in the past, for in the ‘star harvesting’ scenario of Hooper, the spectrum of starlight from a galaxy that has already been harvested would be dominated by massive stars, with the lower mass stars being already enclosed. On this score, it’s also interesting to consider the continuing work of Jason Wright at Penn State, where an analysis of Dyson Spheres as potential energy extractors and computational engines is changing our previous conception of these objects, resulting in smaller, hotter observational signatures.

In the near future we’ll dig into the Wright paper, but for today it’s useful indeed, because it points to why we speculate on such a grand scale. Let me quote from its conclusion:

Real technological development around a star will be subject to many constraints and practical considerations that we probably cannot guess. While we have outlined the ultimate physical limits of Dyson spheres, consistent with Dyson’s philosophy and subject only to weak assumptions that there is a cost to acquiring mass, if real Dyson spheres exist, they might be quite different than we have imagined here.

And the key point:

Nonetheless, these conclusions can guide speculation into the nature of what sorts of Dyson spheres might exist, help interpret upper limits set by search programs, and potentially guide future searches.

But back to Hooper and the subject of Deep Time. For Hooper’s calculation is that all stars that are not gravitationally bound to the Local Group (which includes the Milky Way and Andromeda, among other things) will move beyond the cosmic horizon due to accelerating expansion on a timescale of 100 billion years. It will be autumn among the galaxy clusters, meaning that their energies will need to be harvested or rendered forever inaccessible. Our hypothetical advanced civilization will need to begin moving stars back toward their culture’s central hub. Hooper sees a civilization conducting such activities out to a range of several tens of Mpc, which boosts the total amount of energy available in the culture’s future by a factor of several thousand.

This is an application of Dyson Spheres far different from what Freeman Dyson worked with, and I agree with Jason Wright that technologies of this order are probably far beyond our current imaginings. But as Dyson himself said in a 1966 tribute to Hans Bethe: “My rule is, there is nothing so big nor so crazy that one out of a million technological societies may not feel itself driven to do, provided it is physically possible.”

The paper is Hooper, “Life versus dark energy: How an advanced civilization could resist the accelerating expansion of the universe,” Physics of the Dark Universe Volume 22 (December 2018), pp. 74-79. Abstract / Preprint. The Wright paper is “Application of the Thermodynamics of Radiation to Dyson Spheres as Work Extractors and Computational Engines, and their Observational Consequences,” The Astrophysical Journal Volume 956, No. 1 (5 October 2023), 34 (full text). I drew the Dyson quote from Wright’s paper, but its source is Dyson, Perspectives in modern physics: Essays in Honor of Hans A. Bethe on the Occasion of his 60th birthday, ed R. Marshak, J. Blaker and H. Bethe (New York: Interscience Publishers) July, 1966, p. 641.

A Look at Dark Energy & Long-Term Survival

If life can organize into sentient beings around stars other than our own, there are few assumptions we can make about the civilizations that would emerge. We’ve long ago given up on the idea that such creatures would look like us, just as we abandoned the concept of life on every conceivable astronomical object. William Herschel, among others, thought life might exist on the Sun, a notion that in different form may be coming back around, as witness the growing interest in panpsychism and stellar consciousness. But let’s talk about physical life forms rather than energy fields.

Since we have to assume something somewhere, let’s posit that any civilization would select as its top priority its own survival. That seems obvious enough. Survival demands energy, and that demand increases as the civilization grows through the Kardashev scale, gradually using more and more of the energy of its star and ultimately going beyond that to look for energy sources elsewhere. Dyson sphere thinking comes out of this realization, although we have yet to identify such structures if they do exist.

We need to (temporarily) forget Dyson and acknowledge that energy collection could take forms that are on the edge of our own fancy. Even science fiction at its best can’t imagine everything, and the vast hordes of astronomical data swelling our databases may contain things that we can’t identify as artificial constructs or activities. But we have a universe to play around in, and let’s take this cosmos to its logical conclusion. We know that it is not only expanding, but that the expansion is in fact accelerating.

The Hubble Constant, which relates the rate at which galaxies are receding from us as space expands to their distance from us, is not so constant after all. Or put another way, this value (currently considered in the range of 67.4 km/s/Mpc to 73 km/s/Mpc) actually varies over time. Those figures show the discrepancy between observations with the Planck satellite of the Cosmic Microwave Background and measurements using Cepheid variable stars. Thus the ‘Hubble tension,’ which is all about trying to resolve this difference. Whatever that result, current thinking is that as the universe ages, the expansion rate increases thanks to the interplay between gravity and dark energy.

Now since we’re already getting into mind-blowing territory here, let’s do what Dan Hooper did in 2018 and ask ourselves what a civilization with the vast skills of a Kardashev Type III civilization (one that can control the energies of an entire galaxy) might do to ensure its own future. We’re assuming a civilization that intends to maximize its energy use and must thus overcome the problem of spatial expansion. Because as Hooper points out in a paper in Physics of the Dark Universe, within 100 billion years, all matter not gravitationally bound to our own Local Group of galaxies will become what he calls ‘causally disconnected’ from the Milky Way.

Image: Dan Hooper, in an image provided by the University of Chicago.

Beyond This Horizon is the wonderful title of a Heinlein novel first serialized in Astounding in 1942 and later released in book form. Heinlein was interested in reincarnation, but in this case, the horizon we’re talking about is the ‘edge’ (forgive the metaphor) of the rapidly expanding universe, assuming that dark energy as we currently describe it is correctly understood. That last is the other key assumption that Hooper makes in his paper, the first being the need for civilizations to keep finding new sources of energy. And that’s it as far as assumptions go in this intriguing paper – two and no more.

Hooper (Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory, University of Chicago) points out that a Kardashev III civilization will understand that dark energy will increasingly dominate the total energy density of the cosmos, so that expansion goes exponential. Distant galaxies begin to cross this horizon, rendering them forever out of reach. Energy collection could involve collecting stars – the stellar harvest I mentioned in an earlier post, here seen at its most stupendous scale. The more stars that can be harvested – i.e., propelled toward the civilization’s center – the more stars will become gravitationally bound and thus rendered safe from being lost to the effects of this dark energy.

But we’re not talking about all stars. We need a subset of them. After all, stars aren’t static; they continue to evolve as we go after them. Listen to this, as Hooper considers two different rates of travel for the civilization to reach and ‘rescue’ stars:

…very high-mass stars will often evolve beyond the main sequence before reaching their destination of the central civilization, while very low-mass stars will oftentimes generate too little energy (and thus provide too little acceleration) to avoid falling beyond the horizon. For these reasons, stars with masses in the approximate range of M ∼ (0.2−1)M☉ will be the most attractive targets of such an effort.

So we’re in Dyson sphere country after all, but a revised version of same. The author is talking about transporting usable stars by enclosing them to capture their energies and then applying that energy to the stars as thrust. We have to harvest stars, as the above quote makes clear, that are luminous enough to provide enough thrust, and avoid stars that are ‘fast burners’ and will not reach the central civilization in time to be useful. Hooper continues (again, notice that he’s running his calculations on two different velocities for moving stars; he deploys three velocities elsewhere in the paper):

A civilization that begins to expand in the current epoch, traveling at a maximum speed of 10% (1%) of the speed of light, could harvest stars in this mass range out to a co-moving radius of approximately 50 Mpc (20 Mpc). Unlike more conventional Dyson Spheres, these structures would not necessarily emit in the infrared or sub-millimeter bands, but would instead use the collected energy to propel the captured stars, providing new and potentially distinctive signatures of an advanced civilization in this stage of expansion and stellar collection.

Hooper plugs in a speed of transport of no more than 10% c. It’s an arbitrary choice that may raise an eyebrow or two given that we’re talking about civilizations that have had billions of years of experience in matters of science, technology and propulsion. But let’s take this conservative value for velocity, and the lesser ones he discusses as useful parameters. The idea is that the Dyson spheres being used can transfer all of their collected energy into the kinetic energy of the captured star.

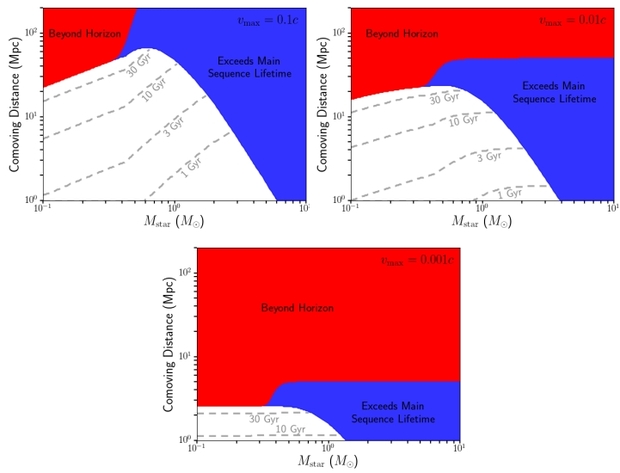

What we wind up with is this: If we assume a maximum speed of 10% c, the advanced civilization could collect stars that are currently as far away from it as 65 Mpc. The numbers are spectacular. Remember, a megaparsec (Mpc) is one million parsecs, or 3.26 million light-years. There are a lot of stars to play with in that volume. Here’s Hooper’s Figure 2 portraying the results for the three velocities he considers in the paper.

Image: Figure 2. A summary of the prospects for an advanced civilization to transport usable stars to a central location, assuming that such efforts begin in the present epoch. Stars in the red (upper left) regions will ultimately fall beyond the cosmic horizon, while those in the blue (right) regions will evolve beyond the main sequence before reaching their destination, and thus not provide useful energy. The grey dashed lines denote the length of time that is required to reach and transport the star. We show results for transport that is limited to speeds below 10%, 1% or 0.1% of the speed of light, and assume that the Dyson Spheres transfer approximately 100% of the collected energy to the kinetic energy of the star (η = 1). The blue region in each frame has been calculated for the optimistic case of stars that are starting their main sequence evolution at the time that they are encountered… Credit: Dan Hooper.

The author then proceeds to adjust for stellar age, which takes into account the fact that we aren’t getting to each star at the beginning of its main sequence evolution:

Integrating our results over the initial mass function of Ref. [34] and the cosmic star formation rate of Ref. [35], we estimate that an advanced civilization (with vmax = 0.1c and η = 1) could increase the total stellar luminosity bound to the Local Group at a point in time 30 billion years in the future by a factor of several thousand relative to that which would have otherwise been available. Over a period of roughly a trillion years, the total luminosity of these stars will drop substantially, but will continue to produce substantial quantities of useable energy due to the longevity of the lightest main sequence stars.

So we can’t shut off dark energy but a sufficiently advanced civilization can extend its lifetime considerably. In the next post, I want to dig into the kind of technosignatures we might find if we happened across this kind of star harvesting in our observational data. In doing this, we’ll certainly not be limited to observations within the Milky Way, but have the entire visible universe to consider. Clément Vidal has examined pulsar imagery that could flag the kind of ‘spider’ pulsar engine described in a recent article here. The technosignatures involved in Hooper’s scenario may be even more tricky to find.

The paper is Hooper, “Life versus dark energy: How an advanced civilization could resist the accelerating expansion of the universe,” Physics of the Dark Universe Volume 22 (December 2018), pp. 74-79. Abstract / Preprint. In addition to several books and numerous scientific papers, Hooper has co-produced an excellent podcast called Why This Universe? whose archives are available here.

Close-up of an Extragalactic Star

While working on a piece about interstellar migration as a response to the accelerating expansion of the universe for next week, I want to pause a moment on a just announced observation. I’ve always had a fascination with the Magellanics, those satellite galaxies that are so useful to astronomers because their gravitational interactions with the Milky Way render both of them irregular in shape. That triggers waves of star formation and tells us something about how galaxies assemble themselves. The Small Magellanic Cloud (SMC), about 200,000 light years away, shows little structure, while the Large Magellanic (LMC) is a bit more organized but lacks symmetry – no smooth disk apparent there.

Image: This beautiful image taken at ESO’s Paranal Observatory shows the four Auxiliary Telescopes of the Very Large Telescope (VLT) Array, set against an incredibly starry backdrop on Cerro Paranal in Chile. The Auxiliary Telescopes are each 1.8 metres in diameter and work with the four 8.2-metre diameter Unit Telescopes to make up the world’s most advanced optical observatory. The telescopes work together to form the VLT Interferometer (VLTI), a giant interferometer which allows astronomers to see details up to 25 times finer than would be possible with the individual Unit Telescopes. Hanging over the site are the prominent Small and Large Magellanic Clouds, visible only in the southern sky. These two irregular dwarf galaxies are in the Local Group and so are companion galaxies to our own galaxy, the Milky Way. The image was taken by John Colosimo, who submitted it to the Your ESO Pictures Flickr group. Credit: ESO/J. Colosimo.

Within the LMC, some 160,000 light years away, astronomers have just imaged a rapidly evolving star, a fascinating catch because the object is dying and we apparently see it just before a supernova event. The telltale sign is the massive ejection of stellar material. The work was done with the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope Interferometer (VLTI), which combines the light collected by four telescopes, using the GRAVITY interferometer, correcting for atmospheric turbulence and providing imaging at four-milliarcsecond resolution. The effect is to produce the spatial resolution of a telescope of up to 130 meters in diameter depending on direction in the sky.

Long-studied and known as the ‘behemoth star,’ WOH G64 has shown surprising changes over a relatively short period of time. Keiichi Ohnaka (Universidad Andrés Bello, Chile) describes a star that is blowing out gas and dust in the last stages of its progress toward becoming a supernova: “We discovered an egg-shaped cocoon closely surrounding the star. We are excited because this may be related to the drastic ejection of material from the dying star before a supernova explosion.” Co-author Jacco van Loon (Keele University, UK) adds: “This star is one of the most extreme of its kind, and any drastic change may bring it closer to an explosive end.”

Shedding their outer layers, a red supergiant may take thousands of years to lose material before a supernova actually occurs. According to the paper, red supergiants like WOH G64 experience mass loss rates as high as ∼10−4 M☉ yr−1 — that means the star at this stage is losing on the order of 0.0001 solar masses of material every year. Recent work on other supernovae tell us that the mass-loss rate increases significantly just before the supernova event. It’s also intriguing that some red supergiants at this point of development show mass loss that is not symmetric. As far as I can find, the explanation is that the star is likely interacting with a binary companion. And indeed the paper notes:

The compact emission imaged with GRAVITY and the near-infrared spectral change suggest the formation of hot new dust close to the star, which gives rise to the monotonically rising near-infrared continuum and the high obscuration of the central star. The elongation of the emission may be due to the presence of a bipolar outflow or effects of an unseen companion.

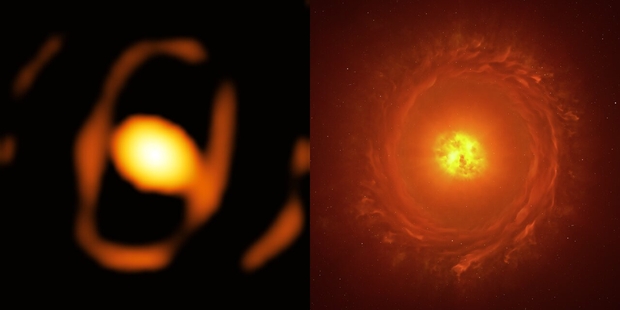

Image: Located in the Large Magellanic Cloud, at a staggering distance of over 160 000 light-years from us, WOH G64 is a dying star roughly 2000 times the size of the Sun. This image of the star (left) is the first close-up picture of a star outside our galaxy. This breakthrough was possible thanks to the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope Interferometer (ESO’s VLTI), located in Chile. The new image, taken with the VLTI’s GRAVITY instrument, shows that the star is enveloped in a large egg-shaped dust cocoon. The image on the right shows an artist’s impression reconstructing the geometry of the structures around the star, including the bright oval envelope and a fainter dusty torus. Confirming the presence and shape of this torus will require additional observations. Credit: ESO/K. Ohnaka et al., L. Calçada.

I suspect that Centauri Dreams readers will remember the Large Magellanic Cloud as the apparent next destination of the interstellar interloper Rama in Arthur C. Clarke’s Rendezvous with Rama (1973). My own favorite reference is Iain Banks’ The Player of Games (2009), where an incredibly complex gaming strategy must be tackled by the protagonist within a strange empire in the Small Magellanic Cloud. Whatever your preference, the Masgellanics continue to fascinate, and we should learn more from the VLTI as the upgraded GRAVITY+ comes online.

The paper is Ohnaka et al., “Imaging the innermost circumstellar environment of the red supergiant WOH G64 in the Large Magellanic Cloud,” Astronomy & Astrophysics 14 October 2024 (letter to the editor). Abstract.

Star Harvest: Civilizations in Search of Energy

Living a long time forces decisions that could otherwise be ignored. This is true of individuals as well as societies, but let’s think in terms of the individual human being. Getting older creates survival scenarios as simple as ensuring safety and nutrition for the elderly. But let’s extend lifetimes to centuries and beyond. In this thought experiment, we create a society of people so long-lived that their personal planning takes in events like a possible asteroid strike in 200 years. A person who could live for a billion years has to think in terms of surviving a dying Sun engulfing his or her planet.

If we assume a kind of immortality, the individual and the society merge in terms of their key concerns. It’s hard to imagine biological beings living for lifetimes like these, but as we’ve often considered in these pages, non-biological machine intelligence, constantly upgrading and improving itself, should be able to pull it off. Because we know of no extraterrestrial civilizations, we can only speculate, but the speculation is a good way to override our anthropomorphic prejudices. And it’s safe to say that any being or society will try to preserve itself in the event of local catastrophe.

Thus the needed insurance of interstellar migration, which philosopher Clément Vidal (Center Leo Apostel, Vrije Universiteit Brussel, Belgium) thinks might involve journeys vast enough to reach places where stars are as plentiful as in the globular clusters surrounding the Milky Way’s hub. Or galactic center, where resources abound and the need for frequent migrations is thus eased. If a culture like this spreads life through its own variant of panspermia, so much the better. I leave the motivations of a machine culture spreading biological life to science fiction authors, but believe me, there’s a cool plot in there somewhere. Someone should run with it.

Vidal’s idea of a stellar engine seizes on an unusual astronomical object, the so-called spider pulsar. We looked briefly at these last time, but let’s dig deeper. We imagine a civilization (Vidal calls them ‘stellivores’) that uses a low-mass star in its home system as a source of fuel, gradually consuming the star’s energies by accretion. So far so good, as we know that accretion is a well established phenomenon. It occurs, for example, in the formation of a Type 1a supernova, where a white dwarf reaches the Chandrasekhar limit (1.4 solar masses or so), drawing in material from a companion red giant through the process. Soon we have runaway nuclear fusion and a bright new object for astronomers to study.

A spider pulsar, a one millisecond pulsar with a very low-mass companion star, can interact not just through accretion but in some cases through evaporation. In reading Vidal’s new paper, I’ve been puzzled by this process, which actually can alternate with accretion in some instances. Things get complicated and quite interesting. Vidal explained in an email that evaporation becomes the primary process when a neutron star has a strong wind that actually quenches accretion and causes the move toward evaporation. Adds Vidal:

The astrophysical reason this would happen is after a long accretion journey, the companion star would get lighter and lighter, the orbit would shrink, up to the point where it is exposed to the strong pulsar wind and radiation. Then the dynamics would switch from accretion to evaporation. A subclass of (redback) spider pulsars, transitional millisecond pulsars, have their accretion that starts and stops abruptly. This is a fascinating phenomenology that has been studied intensively.

And indeed it has, as witness, for example, Baglio et al., “Matter ejections behind the highs and lows of the transitional millisecond pulsar PSR J1023+0038” (citation below), where I read:

Transitional millisecond pulsars are an emerging class of sources that link low-mass X-ray binaries to millisecond radio pulsars in binary systems. These pulsars alternate between a radio pulsar state and an active low-luminosity X-ray disc state. During the active state, these sources exhibit two distinct emission modes (high and low) that alternate unpredictably, abruptly, and incessantly. X-ray to optical pulsations are observed only during the high mode. The root cause of this puzzling behaviour remains elusive.

But back to spider pulsar terminology. You probably noticed the reference to ‘redback’ pulsars. Astronomers divide spider pulsars into black widows, where the companion star is in the range of 0.01 to 0.1 stellar masses, and redbacks, where the companion star mass is between 0.1 and 0.7 stellar masses. Again, the phenomenon Vidal homes in on is evaporation, and it is at the core of the concept of using such a system as an engine. Suppose we look at a transition millisecond pulsar – one of those switching between emission modes – and consider it within the possibility that it is an engine.

Asymmetric heating could be our technosignature as a millisecond pulsar adjusts the heat of its companion star by moving between accretion and evaporation modes to perform, for example, steering maneuvers outside the orbital plane. Asymmetric heating in varying accretion and evaporation phases can compensate for increases in orbital separation. In Vidal’s view, the goal of the binary stellar engine might be to capture a new star whose energies can now be used to supplant the depleted companion and supply the needs of the engine’s creators. Thus the civilization travels to a new star. We imagine a billion-year culture in constant journey mode in search of energy, with the entire galaxy in range.

When we find objects in our data that show transitional millisecond pulsars in configurations that are suggestive, how do we distinguish between technological activity and natural phenomena? As with all technosignatures, it’s not an easy call. As Vidal notes in his email: “Now the game is to make predictions starting with (1) natural, astrophysical hypotheses and models, and (2) artificial, intelligent, “spider stellar engine” hypotheses and models, and see which predictions turn out to be correct.”

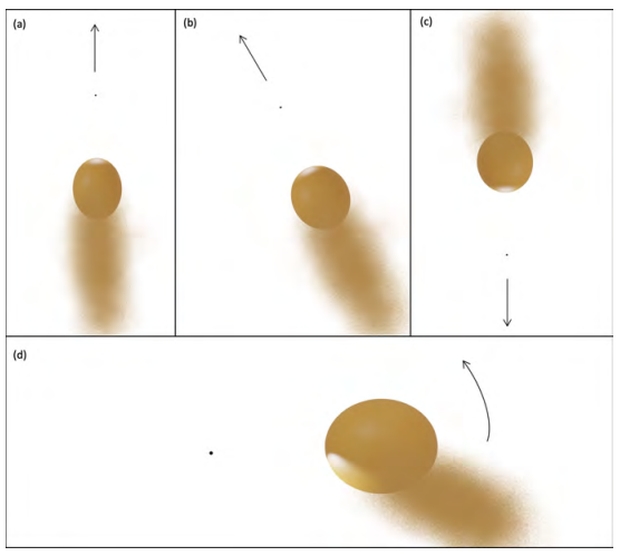

Image: This is Figure 1 from the paper. Caption: Four steering configurations of the binary stellar engine. Figures (a-c) are top views, face on, while figure (d) is side on. In situation (a) the stellar engine is accelerating or cruising; in situation (b), assuming the system velocity is towards the top, the thrust creates a force towards the left; in situation (c), assuming the system velocity is towards the top, the thrust creates a decelerating force. Situation (d) changes the orbital plane by asymmetric heating of the companion, which creates a lifting force in relation to the orbital plane. Note that the pulsar size and orbital separation are not to scale.

The mechanics of acceleration, steering and deceleration are intricate and fully described in the paper, which also includes information on other types of stellar engines going back to the original Shkadov concept – that chart is fascinating. In addition the paper analyzes candidate stellar engines that can be investigated for possible signs of intelligent control. But notice what kind of civilization we may be talking about here. After all, the payload of a spider engine is the millisecond pulsar, the propellant the low-mass companion star. We are thus considering postbiological intelligence on the neutron star itself. I want to quote Vidal’s email on this subject:

…[W]hat really matters is not the hardware of life, but what it does, its software, its functions. Recently we’ve seen with large language models that some form of intelligence can run on computer hardware. Of course, we could change this hardware multiple times and still have the same ChatGPT answering our questions. Life on Earth started with biochemical reactions, now we use semiconductor technology to process data, and we might see optical or quantum hardware taking over in the near future. If a civilization is on a billion-year long track to optimize its hardware and makes the most of the computational capacity of matter in the universe, it would likely continue to improve its hardware using more and more compact, high energy solutions such as nuclear reactions or subnuclear reactions (i.e. neutron star stuff). This is the level I imagine those stellivores are at. So, no planet, no individual traveler. Rather an integrated organism organized around high energy (sub)-nuclear reactions. It might still have some sub-organizations like species, nations, etc. but these would be at extremely small scales and impossible for us to detect.

As with all Vidal’s work, this paper is intricate and deeply researched. About spider engine maneuvering I have had the time only to cover the basics, and encourage interested readers to go to the paper, and also to mine the background laid out in Vidal’s magisterial 2014 title The Beginning and the End: The Meaning of Life in a Cosmological Perspective (Springer). The search for technosignatures demands moving far beyond the assumptions ingrained in our perspective as a species in technological infancy. No one works this turf better and with more elegance than Clément Vidal.

The paper is Vidal, “The Spider Stellar Engine: a Fully Steerable Extraterrestrial Design?” Journal of the British Interplanetary Society Vol. 77 (2024), 156-166 (full text). The Baglio paper is “Matter ejections behind the highs and lows of the transitional millisecond pulsar PSR J1023+0038,” Astronomy & Astrophysics Vol. 677, A30 (September 2023). Abstract. See also Papitto et al., “Transitional Millisecond Pulsars,” in Millisecond Pulsars, edited by Sudip Bhattacharyya, Alessandro Papitto, and Dipankar Bhattacharya, 157–200. Astrophysics and Space Science Library. Cham: Springer International Publishing.