A reminder of how challenging it is to operate with solar power beyond the inner system is the fact that Juno carries 18,698 individual solar cells. Because it is five times further from the Sun than the Earth, the sunlight that reaches Juno is 25 times less powerful, a reflection of the fact that the intensity of light is inversely proportional to the square of the distance from the source.

In other words, if you’re going to use solar power this far out from the Sun, you’d better have plenty of surface area. Juno carries three 9-meter solar arrays that could, at Earth’s distance of 1 AU, generate as much as 14 kilowatts of electricity. But at Jupiter’s distance, controllers are expecting a realistic output of about 500 watts. Making solar power operations possible here is improved solar cell performance and a mission plan that avoids Jupiter’s shadow.

Image: This is the final view taken by the JunoCam instrument on NASA’s Juno spacecraft before Juno’s instruments were powered down in preparation for orbit insertion. Juno obtained this color view on June 29, 2016, at a distance of 5.3 million kilometers from Jupiter. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/SwRI/MSSS.

Planning Rosetta’s Finale

The European Space Agency’s Rosetta mission is coping with the same issue. Rosetta will end its mission to Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko on 30 September with a controlled descent to the surface. The increasing distance between the Sun and the comet alongside which Rosetta travels means that its own solar power will be insufficient to operate its instruments or downlink data. Thus Rosetta is destined to join the Philae lander on the comet’s surface.

“We’re trying to squeeze as many observations in as possible before we run out of solar power,” says Matt Taylor, ESA Rosetta project scientist. “30 September will mark the end of spacecraft operations, but the beginning of the phase where the full focus of the teams will be on science. That is what the Rosetta mission was launched for and we have years of work ahead of us, thoroughly analysing its data.”

Controllers will use much of August to adjust Rosetta’s trajectory, inducing a series of elliptical orbits that will progressively close on the comet. A trajectory change about twelve hours before impact will put the spacecraft on course for final descent. Rosetta will touch down at about half the speed of Philae, but there will be no possibility of communications from the orbiter once it reaches the surface because the high gain antenna will probably not be pointing toward Earth. Even so, we should get some spectacular images at high resolution during the descent.

This ESA news release has more, including mention of the fact that Rosetta entered safe mode last month when about five kilometers from the comet due to dust-related navigation system issues. While the spacecraft recovered, the glitch bears witness to how challenging operations this close to a comet can be. Bringing Rosetta down to the surface may create similar problems.

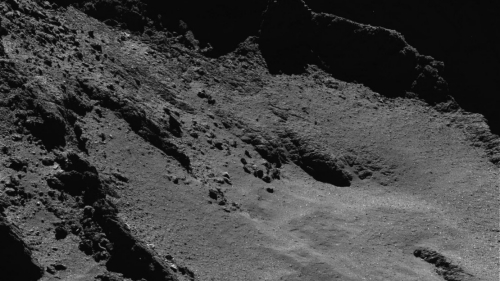

Image: During Rosetta’s final descent, the spacecraft will image the comet’s surface in high resolution from just a few hundred metres. This OSIRIS narrow-angle camera image was taken on 28 May 2016, when the spacecraft was about 5 km from the surface of Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko. The scale is 0.13 m/pixel. Credit: ESA/Rosetta/MPS for OSIRIS Team MPS/UPD/LAM/IAA/SSO/INTA/UPM/DASP/IDA.

Dawn at Ceres

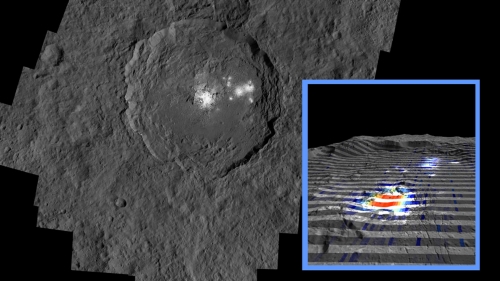

The Dawn spacecraft has been slotted to remain at Ceres rather than proceed on to the main belt asteroid Adeona. What this means is that we’ll be able to stay close to Ceres while the dwarf planet approaches perihelion, an interesting place to be given the many unanswered questions about this world and its unusual bright spots. A new study published in Nature finds that Ceres’ Occator Crater has the highest concentration of carbonate minerals ever seen outside the Earth.

The primary mineral in the brightest area of Occator is found to be sodium carbonate, the upwelling of which is suggestive of warmer conditions inside Ceres than previously believed. Thus we have an intriguing hint of liquid water in comparatively recent geological time, with the salts as possible remnants of a large internal body of water. Says Maria Cristina De Sanctis (National Institute of Astrophysics, Rome), lead author of the paper on this work:

“The minerals we have found at the Occator central bright area require alteration by water. Carbonates support the idea that Ceres had interior hydrothermal activity, which pushed these materials to the surface within Occator.”

Image: The center of Ceres’ mysterious Occator Crater is the brightest area on the dwarf planet. The inset perspective view is overlaid with data concerning the composition of this feature: Red signifies a high abundance of carbonates, while gray indicates a low carbonate abundance. Dawn’s visible and infrared mapping spectrometer (VIR) was used to examine the composition of the bright material in the center of Occator. Using VIR data, researchers found that the dominant constituent of this bright area is sodium carbonate, a kind of salt found on Earth in hydrothermal environments. Scientists determined that Occator represents the highest concentration of carbonate minerals ever seen outside Earth. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/UCLA/MPS/DLR/IDA.

The paper is De Sanctis et al., “Bright carbonate deposits as evidence of aqueous alteration on (1) Ceres,” published online by Nature 29 June 2016 (abstract).

On to the Kuiper Belt

New Horizons, has been given the go-ahead for an extended mission, which includes a flyby of the Kuiper Belt object 2014 MU69. Although many of us have been taking an extended mission for granted given New Horizons’ unprecedented success, the confirmation brings a sense of relief. The flyby is to take place on January 1, 2019, offering us the chance to look at the kind of ancient object considered to be a building block of the Solar System. As we look ahead, we still have a wealth of data from the Pluto/Charon encounter to receive and analyze.

What might be the approach to increase solar power in the outer solar system? Presumably increasing the power per unit mass. This could be done with thin film panels, although deployment might be more difficult. Or possibly using thin Fresnel concentrator lenses, although the trade off is the required orientation to the sun. Given the shortage of material for RTGs, I would hope that engineers are working on better solar power to increase the range of spacecraft, at least out to Saturn where the sun’s energy is just 1% of that at Earth’s orbit.

Thin films don’t generally work, because radiation damages the active semiconductor layers in the cells. Space solar panels therefore use a Cerium-doped cover glass over the front of the cell, and the bulk of the cell thickness protects the back.

For a while, the power needs of communications satellites outpaced the output of the cells, and so a few satellites used reflectors on the array wings to double the collection area. Reflectors are lightweight, but add complexity.

More recently, the cells shifted from single-layer silicon to triple-layer cells that absorbed different wavelengths. This increased efficiency enough (to 30% currently) that reliability was the more important factor. Satellites are very expensive, so even a small chance of the arrays not unfolding properly is not desirable. If extra power is needed for outer solar system missions, reflectors can be brought back as an option, and use higher than 2:1 collection areas. Eventually you can borrow from solar sail technology and get high ratios of collection area for not much mass.

That is not my understanding at all. John Mankin (Space Solar Power advocate) has stated that thin film PV actually is better than silicon regarding radiation damage. A quick perusal of Google shows that thin films are quite adequate for space applications with an abundance of supporting references.

The issue of performance so beloved by engineers when cost is of no importance is not that relevant as we move into the NewSpace era where commercial demands for lower cost based on less than optimum performance is desirable.

I believe the europeans (ESA) are working on an RTG using americanium for fuel. Europe has a good supply of americanium, as it is a waste product from their civil nuclear program. This fuel does not run as hot as plutonium, but lasts longer.

Any bets that extended New Horizons brings us surprises?

I think it likely. There are about 1250 known Kuiper Belt objects, which means several will be close enough to the spacecraft path to observe better than from near-Earth telescopes, although only one will be a close flyby.

Ice worlds always bring surprises. This seems to be one of the general rules of space exploration.

Regarding power supply at Jupiter. I am not an engineer, but I hang around some smart ones. One of the ideas that has rubbed off on me is remote power transfer , which is used (for example) in radio-frequency (RF) ID chips, of the kind that you swipe at a reader to gain entry into some buildings). The system operates when the reader transfers RF power to the chip, which then uses the power to send a signal. Long preamble, but Jupiter is an immensely powerful RF emitter. Surely a similar method could be used to (at least partially) power some equipment.

Power beaming is definitely one way to solve this issue, and probably makes a lot of sense for deep space. Check out the posts on beaming on CD, such as this one: https://centauri-dreams.org/?p=25901

A possibly simpler option in the longer term is mining the Moon for Uranium and Thorium. Although He-3 has been often suggested as an energy source, it only occurs in parts-per-billion on the Moon, while U and Th are present in parts per million in some lunar regions. Their energy density therefore swamps by a large factor the somewhat higher output of fusion over fission. And at present we don’t know how to make lightweight fusion reactors, or fusion reactors at all. We do know how to make fission reactors, and procuring the materials off-planet avoids all the political issues of Pu-238.

On the Moon fission based energy would be a lot easier as the radioactive by products could be ionised and accelerated into deep space to decay there or even used as and when for fission fragment based sails.

“procuring the materials off-planet avoids all the political issues of Pu-238.”

It’s true the moon doesn’t have an ecosphere to contaminate.

But weapons grade fissionables will remain a political issue regardless if they’re enriched on earth or off planet.

Interestingly , impressive as JUNO’s solar arrays are they are already obsolete and technology has moved forward to an exciting new area. Two companies , Orbital ATK and most especially Deployable space solutions, DSS, now produce advanced solar arrays on a truly gargantuan scale. Designed to work at low temperatures (historically a weak point for tradional arrays ) they can be fabricated to either fold up for launch or roll out as with DSS’ ROSAT system which is the current favourite . Quite astoundingly an array of up to 250 m2 can be produced , and two of these is enough to provide up to 400W as far out as Uranus . Even these would only way 780Kg and the only complication would be squeezing them into the launch vehicles fairing . The biggest problem such arrays face is producing TOO much power . When at 1AU such an array could produce an incredible 232 Kilo watts , enough to drive even the power hungry VASIMR ion thruster. Without a nuclear reactor in sight.

The biggest filip such arrays provide is enough power for an ion engine , so called Solar Electric Power or SEP . The latest iteration of which , Xenon powered NEXT , requires 7KW for full thrust ( though it can still operate down to 0.5KW) . There are also already plans afoot to construct more powerful engines , with Aerojet Rocketdyne recently contracted by Nasa to build the next generation Hall ion thrusters which require 13 KW . These new ion engines are streets ahead of Dawn’s so effective and high profile NSTAR engine and the plan is to use them for carrying payloads to Mars in the inner solar system while providing Solar Electric Staging for outer solar system targets . Saturn being the most obvious short term.

If the “Ocean Worlds” Enceladus /Titan theme is successful for New Frontiers 4 ( the one after OSIRIS-REX) then SEP NEXT thrusters and advanced solar arrays are available on top of the mission fund . No where near as powerful as conventional engines, but operate continuously and reliably over years of use rather than just the minutes of chemical engines. Accumulation. Even the huge solar arrays don’t produce enough power to operate an ion engine all the way to Saturn , but would act as a stage to say 6AU or beyond even , before being ejected , with a conventional engine then firing as with Juno , to slow the spacecraft into orbit . The large amount of conventional propellant required to do this could be carried because of the SEP staging and far lower propellant ( xenon) requirements of ion engines .

The Nasa Glenn Space research centre has been investigating this for a over a decade . As an example of what it can achieve , combining a NEXT engine and SEP with a Delta IV Heavy could get a 4 tonne probe to Saturn in just 5.5 years , with just the one Earth gravity assist ( cf Cassini with a Jupiter gravity assist or even 5 years for Juno to Jupiter-JUICE will take 7 !) . This is important as from 2019 Jupiter is incorrectly aligned to provide outer solar system gravity assists for twelve years . Not using traditional Venus gravity assists saves on insulation , a significant cost saving on a limited New Frontiers budget .

What a SEP stage system could achieve with the SLS or even a Falcon Heavy remains to be seen but is clearly exciting especially if we are to finally see missions to the neglected Ice Giants that don’t take decades . The expectation is that with both advanced solar arrays and NEXT available for this years New Frontiers 4 announcement of opportunity , and next generation Hall thrusters already under order , SEP is about to become mainstream. Happy times .

To follow up Ashley’s excellent points about new solar array technology:

Deployable Solar Array Systems

Orbital ATK The MegaFlex Solar Array

Obital’s concentrator tech

And these could be boosted using laser power beaming to operate in the outer reaches of the solar system.

As Ashley say, these will provide the power for advanced solar electric engines. Boeing also has an advanced Hall Effect thruster on their X-37b for testing by the military, currently already a year in orbit.

Good to see these technologies really showing their paces.

Thanks Alex. Ironically there is a bit of a disconnect on this. One senior astronomer who has an established background in submitting outer planet mission concepts told me he is waiting before bidding for NF4 Ocean Worlds. In the past SEP based proposals have earned skepticism from the approvals panel on reliability grounds. He is waiting to see if ROSAT solar array ( seemingly the preferred system currently ) gets a financial incentive attached to it which in effect shows its use is to be encouraged as with the optical communications GFE , which has $30 million attached to it. Not to be sniffed at when you’re on a tight budget. Add in the same for SEP and that’s an extra $60 mill ! How many payload instruments does that add up to , especially if reasonably priced flight spares ?

RTGs may be more efficient by mass but are not excluded from the Principal Investigator’s costs and for NF4 are offered at up to $165 million for three, plus handling costs . As opposed to “free” advanced solar arrays which can also substantially speed up your transfer time in combination with also free NEXT for SEP , helping reduce mission operation costs in the process. Glenn found that four Next thrusters ( two per engine ) fired out to 3.5 AU following a Delta IV Heavy launch would get a 4 tonne orbiter to Saturn in under 5.5 years with just one Earth flyby. ( with savings by avoiding going past hot Venus ) The Atlas V wasn’t much worse . That was nine years ago. The current arrays will still operate to twice that distance . The JET Discovery mission concept had an 8.5 year transfer with gravity assist only

. One caveat is despite being light , so weight isn’t a major issue , how do you store these huge arrays even if they role up or fold down? ( up to 500m2 when unfurled)

I like djlactin’s idea of catching Jovian rf power. But that would be an add-on in mass, too.

Indeed, solar power is generally a bad idea beyond Mars. RTG lasts better and is more mass-efficient, but of course not Politically Correct.

A detail: Jupiter is 5.2 AU out, so reduction is 1/27.

You’re absolutely right. Mixed messages. I think the decision to follow this path was made at a time when Pu238 production was deemed surplus to requirements and there sadly wasn’t enough money to research the excellent ASRG concept . Bit of a back track now with introduction of slow reintroduction of isotope production again but it’s going to take awhile to catch up. As I said , even a monster 500m array only gives a couple of hundred watts at Neptune so would still need supplementation with at-least one RTG ,indeed probably more if they want quality instruments for an orbiter rather than low energy “flyby” New Horizons stock.

I may be wrong but the SEP technology being pushed seems to be as much about staging missions to the outer solar system quickly in the absence of Jupiter gravity assists for twelve years from 2019. Glenn have been publishing papers on this since 2007 , using the Atlas V and DIVH though the SLS and Falcon/Vulcan Heavy might be able to haul up a fully fuelled upper stage to LEO and give a spacecraft plus a big load of SEP xenon and conventional “braking” propellant needed an even bigger kick start .

The OBM apparently isn’t keen on anything bigger than New Frontiers missions with Flagship near non gratis bar “one off ” Europa . Thank goodness. With a maximum one third foreign aid thats still pushing it for NF even to Saturn AND with a lot of GFE AND some useful additional financial sweeteners . Especially if you have to pay for the RTGs and their handling costs too as with NF4 . They are offering one at $100 million , two for $135 and three for $165. Saturn not quite so bad for solar power at least . Doesn’t leave a lot of change for payload even using flight shares ( like STEAM from Rosetta ) or high heritage instruments .

Add-on mass? I’d think minimal; after all, an RFID card has NO on-board power source. An additional advantage is that perhaps the solar array can be omitted. (Also, RTGs also have mass).

Here is a September 2015 article from Scientific American …

http://www.scientificamerican.com/article/within-nasa-a-plutonium-power-struggle/

… displaying the political, ideological and money machinations behind the “no nukes” in space probes drive, thereby limiting the amount of Science returned from these PC missions. One can almost wonder why we don’t try windmills out at Saturn … almost :-)

Where is the reference to PC? The shortage of Pu238 is more clearly an economic issue. If it was a PC issue, there wouldn’t be any renewed production at all.

A key point emphasizing this:

Hi Alex,

For PC zoom in on the words: “politically charged”; “nuclear-shy mission planners”; “mission planners now work overtime to justify not using plutonium on missions long thought to require it.”; “The rules say that we can only use a nuclear power system if other options can’t get the job done”; “Lacking a clearly defined boundary beyond which solar becomes unreasonable, and relying in part on relatively unproven technology”; “missions could always be downsized to accommodate solar, sacrificing science objectives to simply get off the ground. But beyond some ill-defined point, presumably diminishing science returns should make solar more trouble than it is worth.” So an argument can be made that solar for space probes is being pushed, no matter what. Which if true would be a shame for Science returns on future missions.

Tangentially related to New Horizons, I guess you’ve seen the news about the Martian giant impact hypothesis for the formation of Phobos and Deimos? The picture I’m getting is of a system a bit similar to the current Pluto system, with the lost satellite being sort of the Martian equivalent of Charon and Phobos and Deimos being the equivalents of Pluto’s small outer satellites.

Yes, a fascinating parallel! I’ve only seen reports about this one but want to look into the story further.

Especially as Dawn has found circumstantial evidence that Ceres may have a Kuiper belt origin . Makes you wonder just what a critical effect Jupiter’s “grand tack” across the primordial solar system had. The argument still rages as to whether Jupiter, as is , has a positive or negative influence on asteroid / comet impacts on Earth .

I suspect on balance it has indeed protected the Earth from regular impacts but not as shield so much as a brush . Sweeping out a vast collection of the rubble , asteroids , KBOs , comets and planetesimals left over after planet formation that would otherwise have pulverised poor old Earth every few million years . Just look at nearby similar stars without large gas giants , let alone mobile ones, such as Tau Ceti and the two neighbouring Eridanis , Epsilon and Indi . All have huge dust clouds and dense multiple asteroid / Kuiper belts . Many other young solar twins too further afield . When WFIRST gets working on direct imaging the Exozodiacal light this all creates will make the task of picking out planets all the more difficult.

Given that Juno is carrying an instrument called JEDI, it’s probably just as well that it’s avoiding Jupiter’s dark side…

And I love the idea of using RFID or some other kind of magnetic coil technology to use Jupiter’s own emissions as a power source.

I was going to put forward an idea that used a mag sail to move around the Jupiter system using the magnetic field for directional movement and power generation, the idea is remarkably simple.

Ha ! If you look at Juno’s payload , the five magnetic field , radio and gravity instruments combined with say the MISE mapping spectrometer , E-THEMIS thermal imager , SUDA dust analyser and the MASPLEX mass spectrometer from Europa Multi Flyby plus say a LORRI derived faint light imager from New Horizons for completeness, would combine as a decent all round package for Saturn , the two Ice Giants plus all their moons. Ten in total. Same as Juno ( if you count the rather cheap looking JunoCam) . Hugely advanced on anything Cassini has and all high heritage , better still if any have mission spares ? If not Rosetta’s mass spectrometer has a spare that was proposed as STEAM in the Discovery JET concept . Gregory Benford would about know far better than me though.

Which touches on the concept of reducing costs by using standard craft with scale economics, rather than designing from scratch for each mission. Technologies improve of course, so building standard platforms with plug and play components would be helpful. Cubesats are in many ways leading the charge in that direction.

From speaking to NAsa mission planners , especially from the influential outer solar system’s group , OPAG, cube seats have limited scope in the hostile environment of the outer solar system , not least the cold as well as the radiation around Jupiter for those who proposed their use at Europa . Short lived and very narrow focus at best . Also if you insulate them and provide a propulsion system plus communication and payload instruments they cease to be so small . Even a 12 U version struggles and the costs begin to run into the millions which rather defeats their point. Miniaturisation is going to have to catch up in other fields before they are to have substantial utility outside of LEO. Got to start somewhere though and I’m sure they have a promising future .

The issue of RTG vs Solar arrays is mainly that of specific power, although other factors are involved, including access to Pu238, handling issues and potential contamination with a launch failure.

Using data from Wikipedia, the Teledyne 238Pu GPHS-RTG 1980 RTG used on the Galileo and New Horizons probes has a specific power of 5.09 W/kg. “Current spacecraft grade” solar PV is ~ 77 W/kg. This suggests that the breakeven is around 3.9 AU, inside the orbit of Jupiter. However, it is claimed that ITO/InP on Kapton foil PV has a specific power of 2000W/kg, suggesting a breakeven of 19.8AU – close to the orbit of Uranus. In practice, assuming that such PV films can be used in space, support structures will reduce the specific power, but clearly there is scope for increasing the range for solar PV.

I would also note that when O’Neill colonies were in vogue, O’Neill calculated that a colony with half its mass in a thin, aluminum conical reflector would enjoy Earth level solar intensity at 2.7 light days out in the Oort cloud. Such is the possibility of concentrating solar energy in deep space. While this might prove unwieldy for a small space probe, it does suggest that there is little inherent limit on using solar power with a good design of concentrator. That is before we even consider beaming power to PV arrays or rectennas on spacecraft.

It seems to me that the development improvements favor solar PV over RTGs except for extreme deep space missions. As ESA doesn’t have access to Pu238 RTGs, that organization will particularly benefit from solar developments for spacecraft power systems.

Ref data: Power-to-weight ratio

Ultrathin film, high specific power InP solar cells on flexible plastic ..

It looks as if a decision has been made to go solar electric though even with SEP staging and monster multi hundred metre arrays , it won’t work beyond Uranus and even there at a push. Just enough to power instruments but the other important function of RTGs that often gets forgotten is that their waste heat is used to warm critical systems in the evilly cold outer solar system . Looking at previous “Ocean moons proposals” , most were RTG powered with the use of waste heat use heavily emphasised .

Though hinting strongly in flavour of solar electric , even the first New Frontiers 4 call recognises this in offering radioisotope heaters for free and although there is a requirement to pay for RTGs ,three have been made available, almost certainly because any long term lander will require at least one , and lander concepts are obviously been encouraged by the offer of the ” government funded engineering” ALHAT system , Autonomous Landing Hazard Avoidance Technology . No one week battery powered job, but something built to last . The sad thing is that the ASRG power source was a great idea and a very efficient , long lasted system that made very efficient use of limited isotope . It’s development was never even officially stopped , just suspended due to lack of research money . Doesn’t augur well for Space reactors even before any legal considerations .

Mark Watney brought that to our attention recently when he drove across Mars. ;)

If you are going to try to use solar energy, you may as well go all out and build solar sails to propel the ships.

Sufficiently lightweight solar sails such as the ones K Eric Drexler researched as far back as 1975 could provide rapid flypasts to all the outer planets (indeed the real issue would be slowing down from high interplanetary speeds). Once the craft has reached orbit the sail could theoretically be repurposed as a massive reflector to concentrate the weak sunlight onto solar panels in order to provide electrical energy.

This could even be developed into a sort of multi part system, with solar sail “rigging” being dropped off by one spacecraft and used as a reflector to power a second spacecraft (a variation of Robert L Forward’s laser driven starship designs).

I’d like to see a design based on that idea. Sail designs that I’ve seen don’t allow for focusing light, so there would need to be some clever design to allow the sail to be reconfigured to focus light on a PV array or even solar thermal engine.

BTW, sails can be stopped quite easily. The sail trajectory is a spiral away from the sun. Reorientating the sail so that the thrust is against the direction of travel will slow the sail. I quite recall Drexler talking about a sail delivering a 1-ton payload to Jupiter orbit, with a potential to make the return journey, in contrast to a chemical rocket requirement to just deliver the payload. It is those ultra-fast sails like that proposed by Starshot for interstellar travel using laser boosting that are hard to stop.

It might not be just a case of RTGs versus PV but a combination of the two:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Radioisotope_thermoelectric_generator#Criteria_for_selection_of_isotopes

“Thermophotovoltaic cells work by the same principles as a photovoltaic cell, except that they convert infrared light emitted by a hot surface rather than visible light into electricity. ”

Once can also consider a solar+ion propulsion system using pv cells that are very light, yet prone to radiation damage and hence not good for the long term, being used in the inner solar system to get a probe up to speed which then detaches itself leaving a probe that uses a RTG.

Solar electric staging has been considered in great deal for over a decDE AT the Nasa Glenn Space research centre who have published on it extensively , especially in combination with conventional launchers . With just a single Earth flyby following a Delta IV Heavy launch , a four thruster 6.9KW NEXT ion drive could stage to beyond 4 AU at full power with today’s a advanced solar arrays , and further still throttled down ( as low as 0.5 KW) . All this could get a four tonne ( half a tonne heavier than armour plated Juno ) spacecraft to Saturn in under five and half years . How that could be improved further by SLS or even Falcon/Vulcan Heavy is open to conjecture .

Even powered down interplanetary craft cost big money in operations . Remember the last minute glitch on New Horizons just before reaching Pluto ? Caused by a cosmic ray hit . Happens a lot , up to twice a year on deep space missions ( Kepler too just recently and famously – a close run thing even with experienced experts on hand ) . It gets sorted because all these missions retain a crew of on call highly skilled engineers 24/7 on the pay role to sort out . Urgently by necessity . So with their salaries ,plus a a full time Skeleton team of also skilled and expensive mission scientists, plus the cost of using the Deep Space Network ( it’s far from free!) all adds up to an unavoidable big sum per year . Reducing transfer times saves money .

“Even powered down interplanetary craft cost big money in operations.”

Why is that? I would think most of what happens is predictable. After all we have been operating in space for a few decades now. I would have expected most of the routine operations to be automated. Is this just bureaucrats empire building, they don’t automate because they want bigger staffs?

Here is a link to an informative discussion on a current Russian project to develop a megawatt class nuclear power supply with suitably sized ion rocket:

https://forum.nasaspaceflight.com/index.php?topic=37957.0

The total weight (with an undisclosed amount of propellant and payload) is around 22,000 kg. The specific impulse is around 7,000 and the acceleration (if I understood the numbers) is about 0.001 g. Given the forgoing, one hundred (100) days of operation would yield a ?V of about 8,640 meters/sec. That would be impressive.

The project has survived various funding challenges and seems to have crucial support. If this project comes to fruition (presumably testing in space to begin in 2020) it will be a game changer for heavy interplanetary probes, transport of large amounts of cargo to lunar orbit and perhaps manned missions to Mars.

22 MT is big. It dwarfs that of large space probes like Cassini, and even the Soyuz craft. Supposedly it is intended for a manned Mars mission, although the Wikipedia entry doesn’t make a lot of sense to me and may be based on a propagandizing RT article that went the rounds of Facebook groups recently.

Power systems need to be scalable to support widely different craft requirements. RTGs fulfil that role for smaller vehicles (but not very small) that need power that is steady, compact and independent of location. Solar PV works well as long as the sunlight is strong enough and the craft can keep the panels exposed and away from damage. There are clearly overlaps. We’ve seen galileo use RTGs, while Juno used PVs. Mars rovers have used PVs, but the Mars 2020 rover will use an RTG. To my mind, where it gets interesting is when we can develop power beaming technology that overcomes the solar intensity issue, allowing PVs or antennas to capture power well beyond the distances that sunlight is too weak. That might be as revolutionary as the electric power grid in changing how energy was delivered to the home or factory. We’ll see.

I just found out that the Dawn spacecraft will NOT leave Ceres orbit and fly to another asteroid. THIS IS GREAT NEWS, because, it can now focus on the last remaining MAJOR MYSTERY at Ceres: AHUNA MONS. Geologists believe that it is an “extrusion dome” of some kind, which can mean that it either resembles the lava dome that formed after Mount Saint Helens erupted, or it could be an extremely exotic form of pingo, in which case the extrusive material would be the result of REPETATIVE freeze-thaw CYCLES! Logic favors the former, because no pingo on Earth even approaches Ahuna Mons in size, but the LATEST MODEL for the PRESENT(keep in mind, Ahuna Mons appears to be a relatively YOUNG feature)interior of Ceres favors the latter because there appears to be NO LIQUID MANTLE out of which magma chambers can form. The chemical composition of the BRIGHT PARTS of Ahuna Mons’ flanks would rule out one of the two competing hypotheses, and MUST BE DETERMINED BEFORE Dawn runs out of fuel!

Ceres may have gas, a buildup of gases of relatively low pressure will be enough to lift the mass of material seen.

Might last till April of next year if all goes well , but permanently operational rather than in hibernation for a brief flyby in three years time. I’m sorry for the Dawn team , but it’s a good call . The question is whether they will risk their dwindling propellant and reduce remaining operational time to go to an even lower orbit . A figure as low as 12 Km has been bandied about which would give unparalleled resolution of the key science areas you mention. It’s done it’s work in is current orbit , so best go out on a high point ( or low !) , if not with the bang of Cassini or Juno , then at last with a flurry of revolutionary data.

Nasa’s adage for missions is flyby , orbiter, probe, lander – not without good reason . Special case for New Horizons given a new target/ frontier , but Ceres is a perfect case in point .

Hearing lot’s of rumors that AT THE VERY END OF THE MISSION, they WANT to TRY for an ECCENTRIC orbit whose PERIASTRON will be ONLY TWELVE KILOMETERS FROM THE SURFACE! So far, this is JUST a rumor, and I SERIOUSLY DOUBT that the plan would get by Planetary Protection.

Why would Planetary Protection be involved? We take asteroid samples that result in direct contact contamination. Are we really expecting Ceres to be alive?

The ONLY asteroids that have been landed on have been BONE DRY, and with NO ICE on or near the surface. ESA, has, of course, landed on a comet, but I do not believe that their agency even HAS a Planetary Protection devision(correct me if I am wrong. The only place WE have landed that has ICE is Mars, and that is a SPECIAL CASE because because the Viking landers landed there BEFORE OUR Planetary Protection devision was set up. Some people on the Curiosity team want to check out what THEY THINK are recurring slope linea on Mount Sharp, but Planetary Protection has NOT given the GO -AHEAD for that YET.

Let’s not be over cautious. If life was that ubiquitous in the solar system, then we might as well give up doing anything other than remote observing. Mars may have had life in te past (and maybe still does) because of conditions in its early evolution, so it is worth being careful initially. But the moment humans step on the planet (2020’s if some have their way) and isolation is over. But Ceres? This is assuming Ceres has/had a liquid ocean, that life got going in this sub-surface ocean, and that it has survived until now. This is a pretty remote chance. And this is enough to stop a low orbit observation attempt? Zubrin may be all gung ho about crapping on Mars soon, but that doesn’t mean that we should be so circumspect that we daren’t do much at all.

Now if we observe an exoplanet near Earth twin, with biosignatures, then I will be all on board with being very careful about contamination. But if we need to interact, well nothing we launch from Earth can be guaranteed perfectly sterile.

Alex Tolley: I ABSOLUTELY AGREE WITH YOU, but Planetary Protection may or may NOT! We’ll just have to wait and see.

Getting to the outer solar system , even with modern propulsion systems , be it SLS and/or solar electric staging , generally still involves a gravity assist of some kind . Jupiter ideally , but within a twelve yearly on/off cycle that is due to close in 2019 , or alternatively ( and not nearly so good ) different combinations of Earth and Venus . There are other opportunities though , presenting occasionally .

Everyone remembers Voyager 2’s momentous grand tour , taking advantage of a once in two centuries alignment of Jupiter, Saturn ,Uranus and Neptune ( if it had ignored a close pass of smoggy Titan , Voyager 1 could have visited Pluto too, thirty years ahead of New Horizons) .

Sadly another little known alignment passed unheralded for a launch this year . Saturn ,Uranus ,Neptune and then a couple of decades later ( the Voyagers are still working after forty years with inferior technology ) Eris as well. What an opportunity lost and a trip to have savoured.

Although I cannot find the exact article at the moment, I recently read that the Grand Tour of the outer worlds and the story that a space probe could only do it once every 176 years is a bit of an exaggeration.

Granted it turned out to be a good one because it got the Voyagers to those worlds in our lifetimes, but the point is that a variety of launch scenarios could take place using Jupiter as the big boost to reach other outer Sol system worlds in reasonable times. We are not stuck in regards to exploring the more distant worlds of the Sol system now that the Grant Tour alignment has passed. We only need the will and funding to make these missions a reality.

An early paper on the original Grand Tour plans:

http://calteches.library.caltech.edu/2805/1/newburn.pdf

With Ceres and its lowish eccentricity are we sure it could have come from the Kuiper belt, I am not so sure, and I doubt Jupiter could have pushed it from too far out inwards?

I’ve made some comments with some pretty FAR-FETCHED ideas on this website in the past, but today I am going for the GOLD MEDAL! Ceres looks a LITTLE BIT like Phoebe(and therefore, that KIND of KBO), BUT, what it REALLY looks like is the Uranian moon, Umbriel. For all intents and purposes, Umbriel(same ALBEDO, same “relaxed” craters)is Ceres in a deep freeze(although the Wunda “doughnut” on Umbriel looks SO SIMILAR to the bright spots in Occator Crater, it makes me wunda – pardon the pun, BUT I COULDN’T RESIST – if the same sort of geothermal activity might be going on there ANYWAY! That’s why we need to RETURN to Uranus with an orbiter PRONTO)! The funny thing about the Uranian moons is that they are all spaced in a PREDICTABLE WAY EXCEPT FOR A GAP BETWEEN ARIEL AND UMBRIEL! Could Ceres have ORIGINALLY resided in the gap, and then have had a VERY CLOSE ENCOUNTER with the IMPACTOR that tipped Uranus it’s side, ejecting Ceres in the process. The whole thing, along with the NECESSARY encounters with Saturn AND Jupiter make this scenario sound WAY TOO VELOKOSKIAN for my taste, BUT WHO KNOWS!

Sorry, I meant “VELIKOVSKIAN”.

Philae has been found via Rosetta images of the comet’s surface:

http://www.esa.int/Our_Activities/Space_Science/Rosetta/Philae_found