I didn’t have the chance to meet Mark Lupisella at the first 100 Year Starship symposium in Orlando, but the publication of Cosmos & Culture: Cultural Evolution in a Cosmic Context in 2013 made me wish I had sought him out. Co-edited with Steven J. Dick (about whom there are so many interesting things to say that I’ll have to carry over into a future post with them), Cosmos & Culture offers essays from scientists, historians and anthropologists about the evolution of culture both on Earth and, most likely, beyond it.

These are, of course, issues we’ve been considering recently in the work of Cameron Smith and Kathleen Toerpe, and in a broader sense they inform many of the SETI and astrobiology discussions we have here. Then Clément Vidal, who is an author and a post-doctoral researcher at the Free University of Brussels, passed along the paper I missed in Orlando, Lupisella’s “Cosmocultural Evolution: Cosmic Motivations for Interstellar Travel.” To be fair to myself, we all missed plenty of papers at the first 100YSS, because there were five simultaneous tracks and it was impossible (at the current state of technology) to be in more than one place at a time.

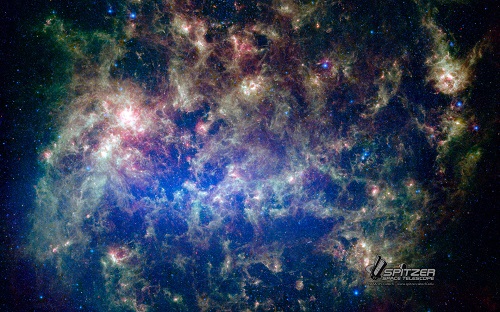

Image: A Spitzer infrared view of the Large Magellanic Cloud, a satellite galaxy to the Milky Way. How we define the human role in a cosmos of such immensity has ramifications throughout our culture. Credit: Spitzer Space Telescope/JPL.

I want to draw on Lupisella’s work this morning because it intersects with an issue I often deal with: How do we state a rationale for expansion into the cosmos? Lupisella discusses a very interesting ‘cosmocultural evolution’ that I’ll get to in a moment, but let’s focus on the motivations for going off-planet that inform any discussion about space. I take it for granted, for instance, that one key driver for a long-term human presence in space is simple survival, the universe being a dangerous place, and our Solar System littered with evidence in the form of space debris and cratered terrain of what can happen when one astronomical body runs into another.

Not everyone agrees with this motivation. I’ve written before about one dinner party where, in the midst of a discussion about everything but the future, one of the guests suddenly asked me why I spent so much time writing about space. It soon became clear that the consensus at the dinner table held that money spent on space was wasted by being diverted from pressing needs on Earth. After I had explained my view that our species needed to insure itself against future catastrophe, my first interrogator said, “Why? I would think that if we found a huge object headed for our planet, we would be doing the universe a favor by letting it hit us and getting it over with.”

So you can’t count on survival as a trump card. And by the way, trying to get past the attitude just cited is probably impossible, because anyone that misanthropic isn’t going to give ground even when reminded that if he did let an incoming asteroid hit the Earth, he would be signing not just his own death warrant but those of his grandchildren and everyone else’s grandchildren as well.

Lupisella sees interstellar flight as “the ultimate insurance policy,” but he brings to the question an added ethical dimension. We should consider our survival as necessary, in this view, because of the possibility that we may ultimately play a role in the broader evolution of the universe. So maybe we want to thrive and prosper not just for ourselves but for the sake of the meaning we can bring to life’s experience in the cosmos.

I find this a heartening view, but let’s add to it some other factors Lupisella pointed to in Orlando. A human presence in space sets up the conditions for countless new experiments in culture and philosophy, which means experiments in everything from social organization to means of governance, all of which would be interesting in and of themselves as well as providing data that could be of use for those remaining on the home world. The cultural experimentation this implies could also be complemented by new contexts for biological evolution — Freeman Dyson has written often about what could happen to our species as we begin to live in radically different environments and essentially begin to fork into various branches of homo sapiens, while the aforementioned Steven J. Dick has explored the emergence of post-biological intelligence.

Cultural diversity flows naturally out of all this, surely healthy for the species, but so does what Lupisella calls a ‘cosmic promotion,’ the reverse of the great demotions we have undergone throughout history as we adjusted our views of the cosmos. We’ve accustomed ourselves to being dethroned from the center of the universe, from being the place around which the Sun revolves, from being at the center of the galaxy, from being in the galaxy as we learned how many of them there are, and so on. Lupisella’s view of cosmocultural evolution suggests that although life, intelligence and culture could arise by chance, they still might have cosmic significance, or as he says, “Modest origins do not imply modest potential.”

Here’s the argument in a nutshell:

If the universe didn’t have value and morality prior, it does now. If it didn’t have meaning and purpose prior, it may now. If it didn’t have intentional creativity prior, it does now. We may be a very small part of the universe that arose by chance, but nevertheless, strictly speaking, the universe now contains morality and a kind of intentional creativity it may not have had prior to the emergence of cultural beings like us. We cultural beings, in some nontrivial sense, make the universe a moral and increasingly creative entity, however limited that contribution may be for now. Increasingly, human culture is expanding its circle of creativity and moral consideration. Perhaps interstellar travel can help expand a circle of moral creativity to the whole of the universe.

Does this remind you of anyone? For me, this is strikingly similar to Michael Michaud’s calls to bring meaning to the cosmos. In one of our dialogues in these pages (see Spaceflight and Legends: A Dialogue with Michael Michaud), the author and diplomat said this:

The moral obligation to assure the survival of intelligence is not imposed on us by gods or prophets, but by our own choices. Call that anthropocentrism if you will. I prefer to think of us as independent moral agents, perhaps the only ones in the galaxy. Until and unless we discover another technological civilization, we have a unique responsibility to impose intention on chance.

I love that phrase ‘to impose intention on chance’ and have used it in several talks. You may have run into Carl Sagan using language a bit like this. When pressed on what happens to humanity in a universe that can seem without meaning, Sagan would reply “Do something meaningful.” I take this to mean, whatever your views, whatever your angle on life, shape events toward a meaningful outcome. Don’t, in other words, let that asteroid hit the Earth. And no matter how bewildered you may be about your place in the cosmos, go forward and do your best.

I draw strength from Lao Tzu: “You accomplish the great task by a series of small acts.” The things we do every day to give meaning to our lives matter. Make them count.

Lupisella notes that in 2007, a panel of experts meeting at the Future of Space Exploration Symposium at Boston University recommended that a 50-year global vision be developed to guide future human space efforts. I am all for such long-term thinking and believe it dovetails nicely with our growing understanding of the meaning we can bring into being as we work. How energizing it is to see the cultural issues of future spaceflight in active discussion. Clément Vidal, by the way, has a book of his own coming out. I look forward to seeing The Beginning and the End: The Meaning of Life in a Cosmological Perspective, just published by Springer.

There are people… people who feel human beings are necessary detrimental to the world. Its Genesis all over again. Set apart from all life by a special awareness, being denied paradise and living a cursed existence.

Humanity is treated like a virus, a disease, corrupting and ruining anything it comes in contact with and ultimately too dangerous tho experience for an prolonged existence.

Then, if we are so dangerous, why haven’t we obliterated ourselves, as we constantly predict? Granted, it was tense at times and it will be tense in the future but so far we didn’t do it.

Its worth exploring why that didn’t happen.

We have become increasingly responsible with our awareness. We learned, like children, that we better not get into conflict with each other. We were not fast learners. We were forced to learn. It needed facing global annihilation as a consequence make us think, but in the end, we did.

Sure, there are many things we do which are irrational. But we also grow increasingly concerned about these issues.

What this is is, in my opinion, is the process of obtaining maturity as a sentient species. We are not a mature sentience… far from it. And we know that.

Following that line, this maturation process seems to be a logical necessity in the transition to an interstellar species. It seems irresponsible species can not spread out to the stars. They annihilate each other in the process. They never make it.

Can we, as a species, become responsible enough? I think this is in any aspect a quite worthy goal.

“to impose intention on chance’”

I like that phrase too. It does not make judgements about whether we have a place in the universe or not, whether we are “[morally] good enough” to expand to the stars, simply that we should. Spreading intelligence was, of course, the reasoning behind Clarke’s aliens traveling the galaxy to cultivate it locally. I would go further and suggest that spreading life to lifeless worlds fits in with this argument. If only we had a “genesis device” to do it quickly.

The universe opens up the possibility of almost infinite diversity. Of life, of civilizations, even machines.

Cultural Evolution: The View from Deep Space

by Paul Gilster on June 11, 2014

A great post!

Biblical people did their best to enshrine your sentiments with their books about God and Man. While the age of religion recedes and I believe becomes I know you’ll find yourself less isolated at dinner parties and surprised to notice that the human destiny is going to be a good one. We are all passengers on spaceship Earth, as Marshall McLuhun has written. Mother nature will continue to impress that fact upon us by putting us in dire straits. Lucky humanity has five oceans to desalt and pipe water to those who need it. Those who go without plenty of fresh water will not survive as an enlightened people. They will want fresh water first…then an international Moon city for 10,000 to ensure against the close calls sure to come from passing rocky visitors from outer space. Ayn Rand would say you worry too much because you and Centauri Dreams do exist and even now are bending the arc of human history…

I reviewed Cosmos & Culture here in 2011:

https://centauri-dreams.org/?p=18702

Another relevant book I reviewed here:

https://centauri-dreams.org/?p=23526

Quoting from the main article:

“Not everyone agrees with this motivation. I’ve written before about one dinner party where, in the midst of a discussion about everything but the future, one of the guests suddenly asked me why I spent so much time writing about space. It soon became clear that the consensus at the dinner table held that money spent on space was wasted by being diverted from pressing needs on Earth. After I had explained my view that our species needed to insure itself against future catastrophe, my first interrogator said, “Why? I would think that if we found a huge object headed for our planet, we would be doing the universe a favor by letting it hit us and getting it over with.”

My response to that utterly ignorant and infuriating comment about “fixing” people’s problems on Earth first before going anywhere else is to say that with that attitude, we should never have done anything at all from the day our ancestors appeared on the African savanna.

We will never fix all our problems so long as we remain fallible humans who continue to overrun this planet by not controlling the birth rate. However, space technology and exploration can certainly help us become a better species on multiple levels – if only the majority of that same species will become educated enough to realize this.

As for his attitude of “good riddance” to the human race if an imminent threat were on its way, how sadly amusing that he does not see the paradox in his two attitudes: On the one hand space is supposedly keeping humans from getting the money it allegedly needs to solve all its problems, but if something came along to wipe us out then somehow that will “save” the rest of the Universe – which he no doubt does not give a flying fig for in the first place!

The only real immediate solution I can see to solving that kind of problem is education. This is why I ask those in the space fields from general fans to real rocket scientists to get out there and teach the public about the Cosmos. If the citizenry fails to support space science, you cannot fully blame them if you did not do your part to at least try to stem the tide of ignorance and cowardice.

Things like starships and SETI should be easy sells, so why aren’t they being funded as they should? Because the public does not look on them as something they can be involved with or have any real relation to their daily lives. We who care about these things need to fix this. Stop waiting for the next Carl Sagan to come along. We need an army of educators to make the public and politicians wake up and support space.

Cosmos & Culture is available for free online in various electronic formats here:

http://www.nasa.gov/connect/ebooks/hist_culture_cosmos_detail.html#.U5hu9PldUWI

This NSS blog shares some interesting quotes from the book:

http://blog.nss.org/?p=1687

And this issue needs to be addressed, as it is a cultural trap Neil deGrasse Tyson of hosting the new Cosmos fame recently fell into as well:

http://www.npr.org/blogs/13.7/2012/05/01/151752815/blackboard-rumble-why-are-physicists-hating-on-philosophy-and-philosophers

and…

http://www.realclearscience.com/articles/2014/05/22/why_does_neil_degrasse_tyson_hate_philosophy.html

The Two Cultures of C. P. Snow need to be reconciled, otherwise we will continue to see the growing divide between those cultures. They need each other if we ever want to truly appreciate and expand into the Cosmos. It was an artificial, human-made divide that created them, so that means it can be solved by human beings.

How ironic, Paul, that you chose a Spitzer image of a celestial object, as that astronomical satellite – one of NASA’s Great Observatories, no less – is currently in danger of being shut down, so the satellite team is considering some rather radical plans to keep it going through 2018, as seen here:

http://www.spacenews.com/article/civil-space/40741spitzer-science-team-finishes-last-ditch-plan-to-save-telescope

To quote:

“Spitzer likely can operate through 2018, Helou said. To get there, the project will have to trim its full-time staff, discontinue some engineering support services and cease efforts to make spacecraft operations more efficient, Helou said.”

Spitzer’s budget for 2014 is $16.5 million – pocket change for most government agencies and big corporations. But I guess Spitzer isn’t sexy or popular enough to warrant the funds and support.

And note this other “loser”…

“The losers were Spitzer and MaxWISE, a proposal to use data gathered by the Wide-Field Infrared Survey Explorer, which NASA reactivated this year, to look for brown dwarf stars. The senior review panel recommended that NASA pursue this mission, which could have been accomplished “for a modest input of funds.”

Anyone who reads Centauri Dreams knows how important it is to search for brown dwarfs, some of which may be even closer to Earth than Alpha Centauri. Some of these objects we catalogue as “failed” stars may actually be rogue worlds or even, – dare I say it? – artificial. Imagine missing those opportunities because the ones with the purse strings can only count beans.

“How do we state a rationale for expansion into the cosmos?”

Don’t need to do that. Just assume it and do it.

So apparently NASA is working on a warp drive starship named… Enterprise:

http://www.extremetech.com/extreme/184143-nasa-unveils-its-futuristic-warp-drive-starship-called-enterprise-of-course

So, are we in the space fields going to capitalize on this and promote the wazoo out of it to excite the public into supporting space science? Just don’t tell them it’s all terribly theoretical, way underfunded, and we don’t have a clue what negative matter is or where to find it yet. Shhhh! By the time they figure it out, we should be all the way to Alpha Centauri… in just two weeks, apparently.

That is fine if using your own resources. If you intend to use communal resources, then you do need to make a case for aligning your goals and plans with the community. Given the expense of interplanetary flight, let alone interstellar, this really is important.

As ljk says: “We need an army of educators to make the public and politicians wake up and support space.” Exactly.

There seems to be a current fashion among some, even the supposedly-well-educated, to effect a sort of “cool”, world-weary cynicism toward imaginative possibilities, especially if they involve noble, organized human aspirations, perhaps especially if they are scientific.

Thus we hear the same old cliches about “solving our problems here, first”, or “there’s no intelligent life on Earth, why should we expect to find any out there?”, or one of the whole line of Hollywood-esque tropes about scientists “playing God” and being punished for their hubris.

Maybe I’m too much the optimist myself, but I think these attitudes often result from a sort of reflexive apathy and lack of understanding rather than a deep-seated nihilistic conviction. I wonder if the misanthrope at the dinner table really feels such contempt for humanity, or if perhaps he was simply trying to appear more “down to Earth” and sophisticated to his friends while discussing a topic he didn’t know enough about to take seriously? Such attitudes might, in some cases anyway, be subject to change (I hope).

I definitely think we should be aware of the fact that the Earth will probably always remain our single best hope for survival. We evolved here. We were made to live on Earth. If we can’t take care of it, I don’t like our chances. The survival argument, to me, seems like a dodge.

By the same token, I don’t care much for what I would call “The thinking animal’s burden”. It’s not an obligation by any means. It’s our privilege and an amazing gift to treasure. But what we do with it is up to us.

I think we should be bold about space and share our enthusiasm for what it is. We shouldn’t be intimidated by people that don’t care about it. I’m happy with saying that space is the greatest adventure we will ever embark on. That knowledge from space tells us about more about who we are and where we come from.

Would I love it if we committed the same resources we committed to building war machines to building space technology? Of course! But at the same time, the challenges of space are like nothing we’ve ever faced before. A slower approach that is squeezed for resources will be a much more efficient way for us to go. I think it’s best that we focus on the highest return scientific missions and the highest return economic objectives until we see some revolutions in our technology and our understanding of physics. Perhaps its best that precious resources aren’t used on building incremental technology when revolutions are needed.

“I definitely think we should be aware of the fact that the Earth will probably always remain our single best hope for survival.”

Well, that’s the point. Not always. That is deep time, astronomical and geological timescales. With regard to the stellar evolution of our home system star, the sun, the habitable time remaining for Earth is something in between 0,5 to 2 billion years.

Of course that does not mean we shouldn’t take care of our planet. That is a long time by human standards. And you are right, its up to us what we do with this knowledge. We can ignore it till Earths surface is too hot to sustain any kind of life, a process which will take considerable time, considerably more time than the more imminent trend of artificial climate change currently underway and such things like creating a runaway greenhouse effect to turn our planet in to a sibling of Venus, for an example.

Other examples include reckless handling of nuclear technology, rogue nanotechnology or artificial genetic creations going rampart, an impact of a sufficiently powerful comet or meteor (which already happened more than once) and so on.

Because that it is not wise to “put all eggs into one basket”, as Professor Hawking put it. Of course its also not wise to destroy the basket intentionally, especially if you have only the one.

Frankly, we should do both.

“Would I love it if we committed the same resources we committed to building war machines to building space technology? Of course!”

Good, lets talk about spending. The Apollo program, financial development considered would be about 150 billion of todays dollars. The current yearly budget for NASA is around 16-18 billion dollars a year. The current defence spending of the USA is about 600 billion USD a year, as much as the ten next highest spenders combined. That totals in approximately 1,2 trillion (1200 billion) USD military spending a year globally, approximately (its more of course, but that are… peanuts). So, to put that into perspective, space-related spending is globally in the single digit percentile, estimated around 3-5% of the military budget globally.

And this is, of course, totally screwed. There are submarine which can launch ICBMs, yes? So how do you improve on that? What is the worth of a large conventional army in these times in any case? What do they want? Invade Russia? That’s where the budget goes to, okay? Surveillance operations which undermine granted rights, etc.

The resources are there. In abundance. Its just… wrong priorities. We invest heavily into self destruction when it should be research and exploration. That’s the problem.

One wonders about a European poll, taken in 1450 about the New World, should such a thing have ever existed. Why sail west? Fix things at home! In the end it was a ruling family’s larcenous heart and the dream of a single person that discovered the Americas.

A stretch? Perhaps.

While we are a messy species at best, at the appropriate times we see those arise who are able to lead us forward. We already see a single person having the best shot of landing on Mars, albeit with some fractional largess from an unwilling government, with tools arguably comparable to the Nina and Santa Maria.

A space beachhead will be established. We will become spacefaring, comfortable amongst our own nine planets and habitats. We will find huge wealth in space as we did in the Americas. The asteroids will create wealth beyond imagination.

And then, we will look outward.

I predict the first interstellar explorers will be due to a super rich individual (or a cult – the two are often one and the same) buying a suitable planetoid, hollowing it out, putting a method of propulsion on one end, filling it full of people of his or her choosing, then launching it out of the Sol system. Probably aimed at an Earthlike world that could be found between now and the time our space colonization infrastructure allows such things to happen. Timothy Leary would have done this if he could have back in the 1960s.

http://www.timothylearyarchives.org/carl-sagans-letters-to-timothy-leary-1974/

@ swage – you know full well what out congresspeople would say to your argument about defense spending. “We need to defend ourselves and our geopolitical interests. Otherwise we might lose everything.”

Since WWII, the US hasn’t actually won a war with “superior technology”. Korea, Vietnam, Afghanistan, and arguably Iraq (the US “won” Gulf 1, but Iraq is a mess today). I really don’t want to see if the US can beat China in a more conventional war.

I don’t think it is unfair to say that the US is undergoing “imperial overstretch”, as outlined by Paul Kennedy in his “The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers”.

If we are going to spend public funds to stimulate the economy, then I agree it would make as much sense to spend it on space as on the military. The returns are likely to be better. (The oil returns from invading Iraq proved illusory). But it isn’t just the US that has made such skewed funding decisions. The Europeans, even Britain alone, could commit to fully fund the Skylon program with barely a scratch to their defense spending. Instead RE is scratching together funds on a piecemeal basis.

I’m not a believer in government “picking winners”. But there is an important role to create markets large enough to encourage private development to capitalize on them. Earmarking funds for those projects by reducing military procurement just a little might be very attractive and an easier sell to the public.

@Micheal Spencer – The Columbus voyages were done for economic reasons, even if the “business model” changed as a result of his discoveries. Can you offer a similar economic rationale for space (no speculative He3 fusion allowed).

Dennis Wingo offered such a rationale – platinum mining, in his book “Moonrush”. The technology du jour was platinum catalyst fuels cells for the hydrogen economy. However it looks like the hydrogen economy doesn’t make that much sense, and fuel cell technology has reduced the amounts of platinum needed. So mining the moon for [cheaper] platinum is apparently stillborn. I expect the same for asteroid mining.

The most valuable resource, IMO, is going to be water. Transporting it to where it is needed in the most economic way will make some people or companies extremely wealthy, if the virtuous circle of supply and demand expansion can be fulfilled.

“to impose intention on chance.” Yes, I like that phrase too. So Paul, given your medieval studies background,perhaps you could write an entry comparing modern scientific/philosophical attemtps to “to impose intention on chance” with medieval religious doctrine that viewed “revieled truth” (from God, scrpture, etc) as a means of adding intention aka purpose to a chaotic world.

@swage “Well, that’s the point. Not always. That is deep time, astronomical and geological timescales. With regard to the stellar evolution of our home system star, the sun, the habitable time remaining for Earth is something in between 0,5 to 2 billion years.”

That sort of timescale is probably beyond the scope of humanity itself. I’m not saying that it will never be important to any sentient life that might be around, but if you’re talking about why I care about space, it’s not because a future that lies outside of my capacity to imagine with any level of accuracy. It really and truly does not get me excited and I wouldn’t expect it to matter to anyone who wasn’t interested in space to begin with.

“Other examples include reckless handling of nuclear technology, rogue nanotechnology or artificial genetic creations going rampart, an impact of a sufficiently powerful comet or meteor (which already happened more than once) and so on.”

I’m not going to deny that having some sort of backup plan would be nice, but if you’re looking for the most efficient way to ensure survival, I just don’t think it measures up right now. The best and most efficient way to meet these threats is head on. I do see space programs aimed at tracking asteroids and preventing their collision as being useful for our survival, for example. Much cheaper and more to the point than trying to colonize an environment that is probably harsher than any of the meteor impacts we’ve seen since earth developed an atmosphere.

When Kennedy pitched going to the moon, he compared it to climbing a mountain. It’s a challenge, and an adventure. At the end of the day, that’s what really and truly get’s me excited.

Joe writes:

Sounds more like a ‘book’ than an ‘entry,’ Joe! Nonetheless, a fascinating idea.

Yet another brilliant entry. If we become the cosmopolitans and seed the galaxy far and wide, then, as John Archibald Wheeler posed, we are the anthropocentric universe, and we do indeed impose our intent and meaning on the universe in a not so existential way. It would be THE way, to add to the Taoist slant Paul gives to the entry, and the exception becomes everything that isn’t animated.

“Not everyone agrees with this motivation. I’ve written before about one dinner party where, in the midst of a discussion about everything but the future, one of the guests suddenly asked me why I spent so much time writing about space. It soon became clear that the consensus at the dinner table held that money spent on space was wasted by being diverted from pressing needs on Earth. After I had explained my view that our species needed to insure itself against future catastrophe, my first interrogator said, “Why? I would think that if we found a huge object headed for our planet, we would be doing the universe a favor by letting it hit us and getting it over with.”

“perhaps you could write an entry comparing modern scientific/philosophical attemtps to “to impose intention on chance” with medieval religious doctrine that viewed “revieled truth” (from God, scrpture, etc) as a means of adding intention aka purpose to a chaotic world.”

These are ‘big picture’ questions, perhaps the biggest. It is outside the scope of the starship topic itself. So my comment below might be seen as off-topic.

Our modern society is confronted by pervasive nihilism and, at best, faces life with an existential angst. The world is in conflict between modernism and a feudal and anti-intellectual fundamentalism that insists nothing exists without precedent, and there is nothing new under the sun. Countless trillions have already been spent in this conflict which, despite declarations of victory, threatens to continue for centuries.

In that scenario there is no prospect for the investment of capital and intellectual resources for the interstellar movement. It is quite wise to consider a 100 year + foundation to consider prospects for interstellar exploration as this is the only way any progress can be made whilst the rest of society is conscripted into perpetual war, deprivation, mind control and ignorance.

As always there are those who seek to perpetuate and profit from this conflict. In the modernist sphere this is a natural result of the cruel nihilism that that builds as a resonant wave from amoral conditions. In the feudal sphere religious fundamentalism gains absolute control to perpetuate and realise its universal death wish.

As an aside, the current conflict of cultures can be compared to the situation in medieval Europe prior to the age of discovery. There was intense competition between Catholic Spain and Portugal related to ability to navigate to the East Indies and the discovery of the New World. The motivation was two-fold: On one hand, the spice trade and, later, discoveries of gold, inflamed the desires of these countries to conquer and exploit these far flung destinations. At the same time, a religio-philosophic justification was developed to gain permission from the Pope to justify the slaughter and enslavement of New World populations, the conversion and salvation of the savage. This lead to the Pope dividing the New World and Far East being between Spain and Portugal. In the course of the reformation, the Dutch, and then the English, succeeded the Spanish and Portuguese as naval powers and the fortunes of the Dutch East India Company and Rue Britannia had their day under the sun.

One might hope that the medieval model could eventuate on an interstellar scale should the world-wide Caliphate be established co-opting Judeo-Christian fundamentalist movements, however the extreme conservatism of these groups and their anti-intellectual and anti-modern worldview. Even in that case, there might be some hope as early Islam treasured knowledge and learning in medicine, science and mathematics and enjoyed its own cosmopolitan golden age whilst Europe was plunged in the dark ages. But this was in the past and there is no indication that such intellectual flowering would take place under a fundamentalist Caliphate. Perhaps they might develop towards an interstellar civilisation in the future, as was envisaged by Frank Herbert’s Dune where the feudal model still in place and interstellar travel is based on paranormal mind-and-space-bending telekinetics rather than on technologically based space warps.

In the continuing conflict it is apparent that Western society’s investment and innovation will be focused on development of weapons delivery and maintaining societal control under harsher and harsher conditions that result from pursuit of war and the neglect of everything else – environment, disease, food security, fresh water, etc. The ruling class becomes increasingly in-bred for its close minded actuarial proclivities and its calculated bloodlessness in dispatching automated armies and robocops. The rest of the population no longer needed become mike the huddled masses resembling the Irish diaspora, yet without any beaconing Liberty to welcome them to new shores.

It’s so easy to become discouraged looking at these scenarios as they continue to develop. As some of the articles on the site have suggested, we may have a very narrow window for progressing our knowledge toward any interstellar goals and some commentators have suggested pragmatic ways to advance while it is still possible.

Understanding that the kind of capital and intellectual expenditures needed for interstellar capability can only be provided by a unified world society, we have to face the fact that elusive world peace is a necessary prerequisite. I remember a Heinlein novel where a sect of Eugenicists were able to commandeer a starship and escape from a war torn earth that was unwilling to support an interstellar voyage. Such outright subterfuge and theft might be a pragmatic way forward, where a secret society infiltrates the military industrial complex and manages to build a starship carefully disguised as a war machine, and then makes a bold escape from a word embroiled in its own self consumption.

Another story I find encouraging in a slow burn sort of way is from A Canticle for Leibowitz (also co-opted by Babylon 5) where following the nuclear conflagration a religious order with esoteric and technical knowledge keeps the faith alive, guiding the reconstruction of society and scientific re-learning over hundreds of years to rebuild in a way conducive to man taking his place amount the stars. I’m sure many stories such as this one and their implications are behind the notions of existential risk and mitigations such as “vessels” discussed on the site.

Meanwhile as we await a global society that can set its sights higher than intolerant fossil fueled turf wars we can celebrate the victories of scientist doing impressive research with bone knives and bear skin equipment, and the entry of private enterprise into the development of space cargo delivery and the business of asteroid wrangling. We already have evidence of the multitude of words within the galaxy and have now even imaged some of them despite the limitations of the resources applied. We will see the moons of Pluto and potentially the sub seas of Europa in our time. And we can watch in wonder as the warp field coil moves from the realm of science fiction to that of scientific theory.

Quality is not bound by number.

@Alex: I take your point, but is it not fair to say that the ultimate reward of the Americas was entirely unseen by the initial explorers?

@Michael Spencer. Obviously the ultimate reward of the Americas was unseen. That applies to almost anything. Because the rewards or costs are unknown, we tend to see the rewarding cases as confirmatory bias. To kick start any endeavor there needs to be some rationale for the effort. That needn’t be economic. But if you want someone else’s funding, then you have to make the case why the funds should go to your project rather than someone else. Investment returns should be influential as they allow greater future funding.

To make your Columbus case, let’s consider asteroid mining. The usual approach is to follow John Lewis and think in terms of rare metals, like platinum (the C21st version of C17th gold). This was the initial carrot dangled by Planetary Resources. Now they dangle the water carrot – water for rocket fuel. (This makes more sense to me, but extracting, electrolyzing asteroid water, then cryogenically cooling the H2 and O2 is not going to be easy or cheap). But at least it has economic logic. The ultimate benefit may be an expanded civilization in space, opening up new opportunities, and new perspectives. Getting to the latter reward is best started through the profit motive, rather than idealism, if only because success will create more funds to expand the effort.

Vision grandiose et optimiste, elle mérite d’être partagée et défendue

Bien dit, Paul !

“I definitely think we should be aware of the fact that the Earth will probably always remain our single best hope for survival. ”

I think that one of the most mistaken comments ever as to need no comment but, just to remove doubt, let me count the ways it is wrong.

1) Regularly hit by meteorites and blighted by supervolcanoes.

2) Severely limited resources

3) Problems with greenhouse gas balance from human activity

4) Surface gravity so high as to cause many humans back problems, and regular deaths just from falling from a normal standing position onto a hard surface.

5) Gravitational well so deep that it puts a barrier between us and the rest of Sol – being so deep that it is impossible to build a space elevator even in theory, unless you accept massive tapering

6) Mixing gasses insufficient to dilute oxygen such that whole forests of living organisms, or whole suburbs can be burnt to the most gruesome of deaths. Once more, high gravity plays its role in helping flames form, and drag in fresh oxygen to keep these horrors going.

7) Sol can support trillions of humans, but if a high portion of those live on Earth, the heat plume of their subsistance living would destroy any semblance of an ecosystem and require massive cooling systems

8) For each large animal here there are billions if not trillions of pathogenic bacteria, many of them specifically evolved to evade our immune system

9) For every bacterium (most are non-pathogenic) there are ten viruses – entities that can only exist by killing living forms.

The truth is Earth is our biggest existential risk. Without it the risk of a pathogen killing all human kind one day would be very low. The sooner leave to Mars and O’Neil colonies, and ban anyone returning from or to Earth the safer we will be. The only way to be completely free of this septic unstable mess is to leave Sol altogether.

@Rob Henry – we need that “septic mess” to survive. We will just be bringing a representative piece with us to Mars, the O’Neill’s and colonies beyond Sol.

Otherwise you make good points.

@Rob Henry June 14, 2014 at 0:08

‘I think that one of the most mistaken comments ever as to need no comment but, just to remove doubt, let me count the ways it is wrong.’

If we learn to keep this Earth safe then we will have learned to keep our world ships, if we build them, safe.

‘1) Regularly hit by meteorites and blighted by supervolcanoes.’

Small ones hit us and thankfully large ones and super-volcanoes are quite rare, but if we were not hit by a huge asteroid we may not be here at all!

‘ 2) Severely limited resources’

We are not limited by resources only the ingenuity to extract them and use then efficiently.

‘ 3) Problems with greenhouse gas balance from human activity’

This is a problem

‘4) Surface gravity so high as to cause many humans back problems, and regular deaths just from falling from a normal standing position onto a hard surface.’

It gives us strong bones and a system capable of surviving launches into space.

‘5) Gravitational well so deep that it puts a barrier between us and the rest of Sol – being so deep that it is impossible to build a space elevator even in theory, unless you accept massive tapering’

Carbon Nano-tube cables would have a taper ratio of around 2

‘ 6) Mixing gasses insufficient to dilute oxygen such that whole forests of living organisms, or whole suburbs can be burnt to the most gruesome of deaths. Once more, high gravity plays its role in helping flames form, and drag in fresh oxygen to keep these horrors going.’

Fire/smoke will always be there even if we reduce the amount of oxygen.

‘7) Sol can support trillions of humans, but if a high portion of those live on Earth, the heat plume of their subsistance living would destroy any semblance of an ecosystem and require massive cooling systems’

That many people on earth is unsustainable.

‘8) For each large animal here there are billions if not trillions of pathogenic bacteria, many of them specifically evolved to evade our immune system.’

Most are not pathogenic, a lot of bacteria are required to aid our existence.

‘9) For every bacterium (most are non-pathogenic) there are ten viruses – entities that can only exist by killing living forms.’

Viruses just want to survive as well, it is just they can be a little to eager to do it.

@Rob Henry

1) I doubt Mars is immune to being hit by asteroids, for example. If anything, it’s thin atmosphere makes them more deadly. The molten core of our world is also responsible for a magnetic “shield” that keeps out harmful radiation. I’m not sure that any super volcano can make the earth worse than Mars or the vacuum of space.

2) Resources are limited, but they’ve supported life for billions of years already. We have yet to find a place with a better track record of supporting life than planet earth.

3) Anthropocentric GW is nothing compared to trying to live on Mars or in space

4) Gravity also keeps in a wonderful self recycling atmosphere that protects us from most meteors and other harmful things

5) Yes we have a gravity well, but if you don’t assume that you need to get off, it’s not that big of a deal.

6) A forest fire is tragic, but it is not a common way for humans to die. Mars’s atmosphere (not to mention its poisonous surface) or the vacuum of space are much more intimidating. Building a structure that could survive a fire is a much easier challenge to meet than a Mars colony.

7) I’m not convinced that we need to number in the trillions to enjoy an excellent chance of survival or that we would be that numerous even if we moved into space. In fact if we become sophisticated enough to colonize space, I expect our population will level off or even retreat some.

8 & 9 ) Even with the prospect of superbugs, I don’t think this represents an existential threat. We were much more vulnerable in the past living in unsanitary conditions without an accurate understanding of disease transmission.

Weaponized diseases are more likely to be devastating and I don’t think we will be immune to military/terrorist actions in space. The same issue is presented with “gray goo” and other man made disasters. Space and other places are just as vulnerable if not more so than Earth to man made disaster.

As I have already acknowledged, having more opportunities for places to live does have benefits. There is wisdom to that idea, but it requires quite a bit of resources. And if resources are limited, you have to make choices.

Losing spaceship earth (that has supported us an our ancestors for billions of years through super volcanoes, solar flares, and meteor impacts) would still the single biggest blow to our chances for our survival I can imagine. Until/when we have maximized our chances for survival on earth, moving to other places isn’t an optimal survival strategy.

Many of the hazards you mentioned could be avoided by having sealed/self sustaining environments on earth. It would be much easier to construct them here. But that wouldn’t be as exciting as colonizing Mars or deep space would it?

Michael says “If we learn to keep this Earth safe then we will have learned to keep our world ships” and I agree, however the best way to save Earth that is from afar.

As we leave Earth and grow to fill the whole system, we will become so numerous as for a desire to return there to present a deadly danger to that planets ecosystem.That system is rather robust, but like the mechanical law that puts stress proportional to strain within elastic limits, the system should hold well right to the point it breaks. We cannot know that point prior without testing on other systems.

Note that description is not perfect. Evolution itself is providing pressure that should have cavitated the system to a simpler one on the timescale by which it creates truly novel genes as outlined by Lovelock. No one has answered this mystery, and no one with the mathematical savvy to model it properly, save Lovelock himself has worked on it much.

The best Lovelock has done so far (to my knowledge) is when he studied the problem of biologically controlled thermostasis. In trying to expand his famous Daisyworld beyond two species he initially hit neigh insuperable problems. In the end, he did find models that could solve it, but only if he allowed more than one stable temperature as points around which it stabalised. Worryingly Earth with its ice ages fits better with this than any current climate model we use to predict global warming.

Thermostatis is, of cause, only one problem, and not as important as our biogeochemical cycles.

@Craig Watkins,

1) I imagine that a terraformed Mars would eventually have a surface atmosphere pressure greater than Earth (N2 imported from Titan by slingshooting waveriders, and He[as a diluting gas] from Uranus and Neptune, all done free of any energy cost), and one that tapers off with a much higher scale height. The killers are that Mars has both a much lower cross-sectional area for their capture, a much lower gravitational focusing effect, and a significantly lower minimum impact velocity.

2) Depletion of Earthly resources to exhaustion or whether we can overcome them is a red herring. It is the unnecessary burden that their cost price places on us and on Earth’s ecosystem that is my concern.

3) see 2)

4) It is currently hotly debated whether that is even true on billion year timescales. It is certainly false for million year ones.

5) see 4)

6) Getting off our world is not a problem. The barrier to the free flow of goods won’t apply to any other populated world’s of Sol (save, perhaps, Venus).

7) The recourses of Sol will provide vast and varied niches into which we can expand. Nothing should stop us other that arbitrary decisions of a immortal dictator, or fertility rate that is too low to keep humanity going.

8&9) Yes weaponisation of infection agents is definitely an even greater risk, but the potential of these weapons is superlatively higher if we all live in one place.

Oops, above I implied that Mars could hold He for millions of years, but never meant it. I actually envisioned He imported for O’Neill colonies, and the Ne that came in the process being separated and used on Mars. Those humans addicted to living on terrestrial planets will always be paying the higher price for it, and I imagine many trillion of those on Mars, their food flowing in from the colonies as freely as if it was just a neighbouring O’Neill due to its shallow gravitational well.

@Rob Henry June 14, 2014 at 21:45

‘…and I imagine many trillion of those on Mars, their food flowing in from the colonies as freely as if it was just a neighbouring O’Neill due to its shallow gravitational well.’

The problem with terraforming Mars is that you will need to thaw it out, it is frozen to great depth. And once you thicken the atmosphere the winds will pick up that very fine dust and visibility will be poor. O’Neill colonies are the way to go, they have great versatility to them, now one parked in Mars orbit, oh the views!

Michael, I believe your thinking as if the plan starts with what we can do in the next century, and thereafter is set in concrete. Think of it this way.

The average American’s energy consumption is now 10,000W and, already usage is becoming uncoupled from GDP. Even if the average person of the far future is a thousand times richer they should only be using 100,000W (if we allow it to get too high, even bringing two people together would become dangerous!). Now there are resource problems with creating a total Dyson swarm, but a 0.1% coverage with 10% efficiency at energy conversion is far easier, and I get a population of 400,000 trillion to grow into.

Only a fraction of those will want to live on terrestrial environments, but dissipating the heat plume of those that do will be the problem, not thawing. Now, intersect that eventual situation with plans set from this time and what do you get? I don’t know, but with current economic growth doubling the economy every twenty years (likely to continue till a limit is neared), talk by some of taking tens of thousands of years to terraform Mars is quite ridiculous.

‘Can you offer a similar economic rationale for space?’

Yes, i can. Total collapse if we don’t do it. See… its not about bookkeeping. Resources on Earth are limited. If we limit ourselves we go down the road every enclosed ecosystem with a growing population is heeded: death.

Rational enough?

‘That sort of timescale is probably beyond the scope of humanity itself.’

Probably. But thought ‘too human’. Life endured longer than that already. And life advanced. I do not know if there will be anything like humans around at that time (probably not), but SOMETHING will. And these will be our descendants.

We are looking at them with indifference. That is the crux of the problem. And not only in deep time scale, but also very short therm: climate change, etc. That is just unacceptable. We are acting irresponsible. What kind of parents would do this to their children? That line of thinking HAS to stop.

And for what are sacrificing the future? To go for each other throats. That’s just ridiculous.

“The best and most efficient way to meet these threats is head on. I do see space programs aimed at tracking asteroids and preventing their collision as being useful for our survival, for example.”

That is certainly a good idea, but there are limits to what we can do. We can’t do anything about a neutron star heading our way. That is why ultimately colonization is the only way to go.

We don’t need a cheap solution here. We need a good one.

The survival motive for permanently entering space, while rational, still hasn’t captured the public and politicians enough to motivate them to fund space science and technology properly.

I know they expect if humanity is in danger of the sort that requires our escaping Earth that a bunch of smart guys will suddenly appear, build a Worldship in the nick of time, and off we go. For the same reasons they now think that NASA is working on the USS Enterprise.

Gaining the geopolitical high ground, making tons of money, and specific groups wanting to leave our planet to live lives their own way, those are the motivations that will get us out there. Science will go along for the ride, as it usually has, rather than being the prime motivation, as it should be.

So to the space fans, perhaps you should focus on those motivations rather than telling the public we need to get off Earth before a giant asteroid strikes us or the Sun explodes (yes I know our star will not go either nova or supernova, but the public often thinks otherwise). Because clearly mere survival is not enough plus it just makes space look like an escape route and little more.

Maybe throw in some wonder and cosmic perspective expansion for good measure. Oh yes and the environmental angle: Less people on Earth, more chances for the other native flora and fauna. Earth as a big nature preserve.

@ swage.

You are making the assumption that economic growth using more resources must continue. That is not necessarily true. We could have a fairly steady state economy, with no growth, although it would be a very different economy and world.

But let us see how far that growth could continue. Using Rob Henry’s 10^5W/person and 400T people as an example, if we assume just 2% economic growth, we get to that level of energy consumption from today’s 1.6 TW in less than 750 years. [population growth would be just 1.5% pa over the same time frame.] If we assume 100 bn stars in the galaxy to populate with Dyson swarms, at that 2% rate of growth, it would take just 1275 years more – impossible as we cannot traverse the galaxy in less than 100k years w/o FTL. So call it 1000 years of further moderate growth and that is it. Like it or not, our growth economy cannot continue to grow using energy and resources in a linear relationship. It must become either increasingly weightless or slow to pre-industrial revolution pace – i.e glacial.

But imagine such a civilization of 4E14 people, living in space colonies scattered throughout Sol system. How diverse the cultures and technologies. It would appear to be a wonderland to our eyes, even the poorest of citizens would live in luxury compared to our lives today. And the richest…?

And tourism. I want to say the price needs to go down on that from $20 million to Earth orbit or $100 million to circle the Moon, both by the Russians, but as orbiting hotels and stays on the lunar surface that may not be an option. Will there be enough very rich people to make this a thriving industry and eventually allow the “commoners” a chance to see the heavens?

@ljk – space tourism is really the subject for another post. What we do know is that even for spacecraft, the key to ticket price reductions is amortizing the cost of the vehicle over the number of tickets. Fuel is inconsequential. To minimize ticket prices requires airliner rates of flight. So spacecraft must be fully reusable with rapid flight turnarounds and minimal maintenance. The current incumbents for sub-orbital flights are skimming the market while there is novelty, but they expect ticket prices to drop 10 fold over a decade. Orbital flights are much harder, but Skylon is suggesting < $500/kg ($50k/ticket ?) . That seems like a reasonable price for tourists. And if that works, then, as with aircraft, larger, more efficient vehicles with better propulsion systems will drive down the price even further. I saw an article in the NSS magazine Ad Astra, that suggested that power lasers could reduce the cost to orbit to $50/kg ($5000/ticket?). If true, that would open the floodgates to tourism as a flight and a brief stay at an orbital hotel/rest stop would be comparable to a week's luxury cruise.

Alex Tolley writes, “[The economy] must become either increasingly weightless or slow to pre-industrial revolution pace – i.e glacial.” This he shows by normal ‘industrial age’ growth rate with high energy coupling. But how bad would that uncoupling to ‘weightlessness’ be.

Due to the nature of fiat currency and banking, most growth is currently debt based. This is has a destabilising ‘bubble economy’ effect, as does our preference for derivative type financial instruments. That makes high growth look more hazardous than it really is. Currently energy is cheap and plentiful, and that situation will change very soon if we stay on Earth. If resource depletion (including energy availability) declines per capita, there will be a market signal that will begin to decouple it from new economic growth, but it doesn’t mean that it would ever be very much slower than now. Even this low degree of hobbling can be put off by Alex Tolley’s 1000 years if we make it into space. Further more, the availability of space-based resources might be the only answer to some problems on Earth (such as global warming)… Not that there couldn’t be yet other problems

Biomass fuel is an idea that puts the demand for food from our poorest in direct competition with the transport needs of our richest. In a world with low GINI that would be no problem, but is ours really one of those? The current coming crunch wont be pretty according to the doomsayers, with problems like that exasperating it, but, if it comes, it will be in larger part due to our own intransigent, much of it brought on by obsessive love of our pitiful home planet.

@Rob Henry – Assuming, as is likely, the vast majority of Earth’s population will stay put, there will still be a dampening of economic growth as population must stabilize. [econ. growth = pop. growth + productivity growth]. It may be that earth becomes much more crowded with access to abundant space based energy and resources, plus factory food production, but I doubt that can safely even reach a fraction of potential of a space based population starting from a relatively small population. Simply dumping more energy onto the Earth will cause warming unless the heat load can be radiated away in some fashion. Space based resourcing will extend possible global GDP for a while, but it must still max out at some point. I would think that this will be well before that happens for the solar system GDP.

What I think is unlikely to occur is the preservation of Earth as a natural environment (whatever that will mean) to be visited by wealthy tourist, much like Yosemite. The Earth will remain crowded indefinitely as the vast majority of the population will want to stay rooted there.

I suspect Asimov got it largely right with his Elijah Bailey stories. Earth will remain crowded, while the spacers will inhabit much wealthier worlds. I substitute O’Neill’s for the spacer worlds of Aurora, Solaris, etc. The potential for growth in the solar system will be even larger than the 50 spacer worlds. In a warming world, cities might even be rebuilt as arcologies, making life imitate art even further, albeit concrete instead of steel for the human caves.

Polish meteorite venerated by Neolithic man? Posted by TANN

A meteorite found in the remains of a Neolithic hut in Bolkow, north west Poland, may have been used for shamanic purposes, academics have argued.

The meteorite was discovered among a large group of sacral objects in a hut on the banks of Swidwie Lake in the West Pomeranian region. Archaeologists from the Institute of Archaeology and Ethnology in Szczecin found items including an amulet, a so-called ‘magic staff’ fashioned from antlers and decorated with geometrical motifs, and an engraved bone spear. They were made about 9000 years ago.

Full article here:

http://archaeologynewsnetwork.blogspot.it/2014/06/polish-meteorite-venerated-by-neolithic.html#.U6G0j_ldUWJ

With cults committing suicide due to comets, people thinking that solar and lunar eclipses are signs of the end of the world, and seeing stains on a wall or in French toast as messages from their deities, are we really that different culturally from Neolithic humans worshipping a meteorite? At least they had ignorance of astronomical science as their excuse.

Alex Tolley asks “What I think is unlikely to occur is the preservation of Earth as a natural environment (whatever that will mean) to be visited by wealthy tourist, much like Yosemite”. And I have to wonder if there is actually a reason he thinks so. After all, he acknowledges that spaced-based humans will potentially be far more numerous, and prosperous than the poverty stricken remainder they left behind.

In his next sentence he does give something of that with – “The Earth will remain crowded indefinitely as the vast majority of the population will want to stay rooted there”.

I don’t doubt the likelihood that most of Earth’s population will always be too poor to leave without compensation. What I do doubt is that the colonists will never outnumber them via their own, less inhibited, growth, and that their wealthy will never have the funds to fix that problem, and consider it a minor consideration (one possibility is to bribe those polluting slum dwellers to move off Earth)

I suppose a cynic would say everyone has their price. Are there good historical examples that show that has been a successful strategy? How easy it would have been to solve the movement of American Indians in the C19th. Or what about re-establishing Israel in Nevada? Britons were bribed to go to Australia until 1973, yet England remains more populous than Australia (Was it really about the lack of a really good cup of tea?)

The suggestion that Earth could be allowed to return to some unspoiled, almost uninhabited Eden, just seems unlikely to me. Pockets may be preserved. Far more likely to me is KSR’s inflated asteroids with their own designed ecologies (2312: A Novel) – a sort of sophisticated Disney World ecosystem. And so much better for recreating varied paleo ecologies: Pleistocene Park, Eocene Valley, etc.

I can see one reason why the rich space colonists might want at least some of the poor from Earth up in space with them: Cheap, replaceable labor. Assuming work machines remain too expensive and complex especially in a space environment.

Again, it appears likely that the real reasons we will colonize space are the same as those who went to colonize the New World and Australia: Riches, land, freedom, and getting rid of societal undesirables. We confuse our new shiny toys with being superior to our ancestors. At least they tended to be honest about their motives.

We like to say we go into space for science and expanding human knowledge. That is but a byproduct, otherwise governments and industry would never have funded space exploration to begin with. You really think we sent humans to the Moon to bring back its rocks?

@Alex Tolley

“Like it or not, our growth economy cannot continue to grow using energy and resources in a linear relationship.”

And neither should it, the point made is: if we stay on Earth we will ultimately use up all resources until… it becomes unsustainable. The model is not linear economics. A far better model is biology, with adaptive growth, as resources are encountered and more niches become available or resources decline and are used up.

It can not summed up in a linear projection of rising energy need, that’s overly simplified.